Uzbekistan Nov 5-17 2015

This is Central Asia’s cradle of culture for more than 2 millennia, the home of an arsenal of architecture and ancient cities, all deeply infused with the bloody, fascinating history of the Silk Road. In terms of sites alone, Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s biggest draw.

Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva impress visitors with fabulous mosques, madrassas and mausoleums. Other sites include the fast disappearing Aral Sea, the fortresses of remote Karakalpakstan, and the boom town capital of Tashkent.

Despite being a harshly governed police state, Uzbeks are extremely friendly where hospitality is an essential element of daily life. Karimov died in September 2016 – the obituary on TV mentioned the repressive police state, forced labour in the cotton fields and the massacre in 2005. The West was criticized for being shamefully neglectful in not criticizing Karimov and his regime.

Area. 447,400 sq km

Capital. Tashkent

Population. 30 million.

Languages. Uzbek, Russian, Tajik, Karakalpak. Uzbek, a Turkic language, is official, has 15 million speakers and is the most widely spoken non-Slavic language from the former Soviet states. It was first written in Arabic, then in Roman letters, and since 1941, in a modified Cyrillic alphabet, but has been moving back to Roman.

When to travel. April to June has clear skies and cool temperatures for perfect travel conditions. July and August experience extreme heat and hotels can be a bargain. September and October remain warm.

Famous for plov, carpets, cotton. Pomegranates, Timor.

VISAS. This is the most expensive country in Central Asia to get a visa if you need a letter of invitation.

Letter of Invitation. Citizens of Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Malaysia, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, UK and USA do not need a letter of invitation to apply for their Uzbekistan tourist visa. Citizens of Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Russia and Ukraine have visa-free travel. All other nationals need a letter of invitation from a tour company. It normally takes 7-10 days to process so plan ahead. It cost US$85 for a 15-day visa ($70 for 7 days and $115 for 30 days, $10 for express service but double the consular fee, and $10 for each additional entry).

If you have a LOI, you can usually get the Uzbek visa the same day. If you do not have a LOI (meaning, if you are from a country that does not need one), it will take much longer – 1 week? 10 days? 2 weeks? It depends on your embassy. For this reason, many travellers who don’t need the letter of invitation decide to get one anyway so as not to get stuck too long if they are applying on the road.

Tourist Visa

The Uzbekistan tourist visa is issued for 7, 15 or 30 days. It is date-specific, meaning that entry and exit dates are set on the visa. Cost of the visa is around $55 for 15 days, 90$ for 1 month, double entry is 10$ extra. Americans and Israelis pay 120$ to 165$, Japanese go for free. It is also possible to apply for a visa in one embassy, and pick it up in another one, like with the Turkmen visa.

My experience. I applied for my LOI though the Cavavanistan.com travel site. It cost US$85 for a 15-day visa and arrived 8 days later. The travel company was very thorough and efficient. With the LOI in Dushanbe, a photocopy of my passport and a passport photo, for US$65 (Canada), I had my visa in 5 minutes.

MONEY. The Uzbek Som’s official rate is kept artificially high so everyone uses the black market. In October 2015, the official rate was 2500 and the black market rate close to 4900 in Kokand. But it was 5700 in the Chorsu Bazaar in Tashkent and I was charged 5800 in my B&B and 6000 at Timur’s Mausoleum in Samarkand. It is important to bring sufficient US$ for the duration of your trip as using an ATM will cost you 50% of the value of your money if taken out in som. Most businesses charge black market values. When exchanging money, it is important to get 5000 som notes, the largest value available. Refuse 1000 som bills or you will need a suitcase to carry all the cash. One US$100 bill gets a large wad of bills even with 5000som notes. I am uncertain if it is even possible to buy US$ on the black market – it seems to only work one way. Because the money is devaluing so quickly, the exchange rate changes daily and Uzbeks want US$.

Because Uzbekistan is a black market money country, you do not want to use ATMS or banks to get money. Any withdrawal automatically loses 50%. The only way to deal with money is to bring US$ into the country. No ATMs work because no one uses them. A select few ATMs can be found in Tashkent but you can’t rely on them having cash in them. In other cities, ATMs are rare, and if they work at all, usually work with one kind of card (Visa or MC), and then rarely have cash. There was one in Bukhara, and it rejected the pin on my Visa. To obtain money, one usually needs to go to a bank. Banks are closed from 2-3pm for lunch and then are only open till 3:30 or 4pm so plan on doing any financial business in the morning. A passport is required to enter the bank. Then one needs to find the room that will give cash advances on a credit or debit card (there are many rooms each with a specific purpose and one would probably need to speak Russian or Uzbek to even find the room). After giving your passport again, your card is put into a standard credit card chip reading machine, you enter your pin and maybe you can get money, hopefully in US$. I went to 3 banks and all said that I had entered an incorrect pin (when I knew that the pin was correct). As a result, there may be no way to obtain cash and it is mandatory that one bring enough US$ with you on entering the country. I am uncertain if it is even possible to get US$ at a bank. If you were to get som, it would be at the official rate and it would cost you at least 50%. I purchased a handicraft for which I didn’t have enough US$ and used my credit card in an old-fashioned card swipe machine that required a signature and no pin.

In retrospect, this is all good – I really did not want my debit or credit cards to work (although in my traveling innocence or ignorance, I made a good effort). These would have been been very expensive transactions.

REGISTRATION. It is required that you register somewhere within 3 days of arriving. Theoretically you don’t need to register if staying in a town for less than 3 nights but it is best to register more often. Failure to do so can result in a small bribe to a fine of up to a thousand dollars and deportation. If you go without registering for several consecutive days, you are asking for trouble. A hotel licensed to take foreigners automatically registers you. If you stay in a private home, you are supposed to register with the local Office of Visas and Registration (OVIR), but this causes more problems than it solves for you and your hosts.

When you leave the country, border officials thoroughly scrutinize your registration slips. Campers must resign themselves to staying in a hotel at least every 3 nights.

Internet. In my experience, every hotel/B&B/hostel I stayed in has had excellent wi-fi that is relatively fast. But Skype is blocked in Uzbekistan. One way around the block is to use a VPN (and Skype works just fine then).

I crossed into Uzbekistan from Kandabam/Kanbodom, Tajikistan. To get there was a 1 1/2 hour 7somoni share minibus and a 20somoni taxi. Uzbekistan customs was interesting. I had to fill out a declaration of all the money I had in duplicate to be presented on exit from the country. The forms are all in Russian/Uzbek and would have been impossible to fill out without the help of a tourist at the border post. Then was the most thorough search of my bags I have ever had. I have heard of some people having their computer searched and all medications declared.

I then walked about a kilometer to a store and got a share minivan to Beshank (US$3), changed all my somoni to Uzbek som (am totally uncertain if I got a good rate) and then had another van to Kokand (1600som). This is considerably cheaper transportation than if you go from Khojand via Oybek to Tashkent.

FERGANA VALLEY. Where’s the valley? From this broad (22,000sq km) flat bowl, the surrounding mountain ranges (Tian Shan to the north and Pamirs to the south) are invisible in normal atmospheric conditions. There is often smog in this, Uzbekistan’s most populous and most industrial region.

Fergana is also the fruit and cotton basket. Drained by the Syr-Darya, the valley is one big oasis with some of the finest soil and climate in Central Asia. Already in the 2nd century, the Greeks, Persians and Chinese found a prosperous kingdom and some 70 villages and towns. The Soviets enslaved it to an obsessive raw-cotton monoculture that still exists today. It is also the center of Central Asian silk production centered in Margilon.

Of the 8 million people in the valley, 90% are Uzbek and higher in the smaller towns. The province has always yielded a large share of Uzbekistan’s political, economic and religious influence. Fergana was the center of numerous revolts against the tsar and later the Bolsheviks. In the 1990s, the valley gave birth to religious extremism in Central Asia. President Karimov’s brutal crackdown came to a head in the Andijon massacre in 2005, the memory of which still haunts the region today. There is still a significant police presence.

But they are still very hospitable and friendly. Other attractions are crafts and wonderful bazaars. Dress modesty is best. Security is tight with frequent checkpoints where foreigners must register.

KOKAND (pop 200,000)

This is the gateway to the valley. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was the hotbed and second only to Bukhara as a religious centre in Central Asia, with at least 35 madrassas and hundreds of mosques. Today the centre is hedged by colonial avenues, bearing little resemblance to Bukhara. Nationalists fed up with empty promises met here in 1918, the Tashkent soviet had the city sacked, most of its holy sites desecrated or destroyed and 14,000 Kokandis slaughtered.

Traditionally conservative Kokand today has been made over giving the town a modern feel.

I took a city bus to my hotel (500som). I always try to take city buses. Besides being very cheap, you can have a lot of fun with the locals.

I stayed at the very nice Hotel Kokand, close to the Khan’s Palace. It had great wi-fi, an unusual commodity in Uzbekistan. The price started at $30, but we eventually settled on $20.

Khan’s Palace. Khudayar Khan was a cruel leader forced into exile by his subjects and the Russians snuffed out his Khanate. Roughly half the palace was taken up by his harem. His 43 concubines would wait to be chosen as wife for the night – Islam allows only four wives so the khan kept a mullah at hand for a quick marriage ceremony with the marriage only to last one night.

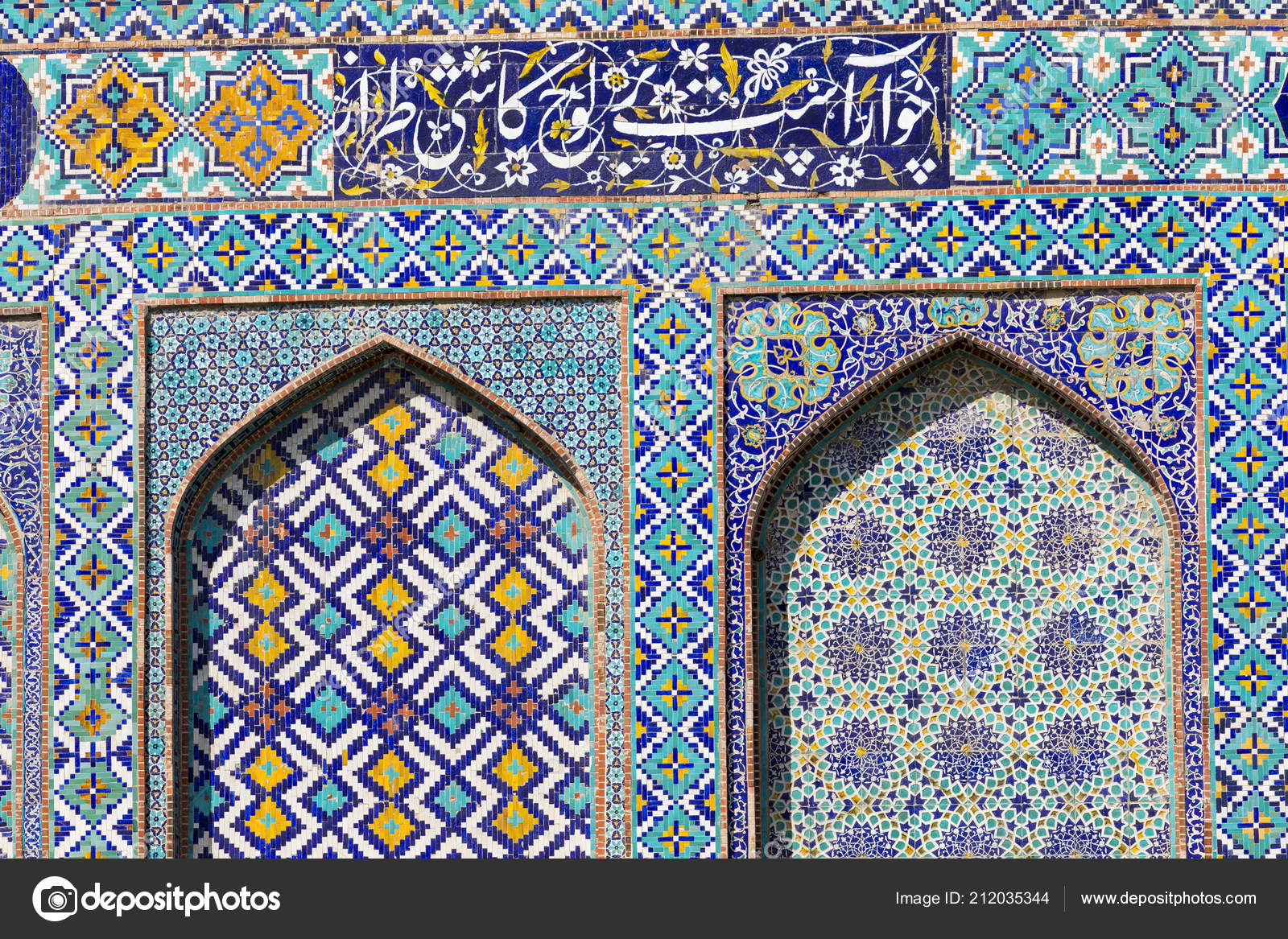

The palace, built in 1873, had seven courtyards and 114 rooms, but the Russians demolished the harem’s quarters in 1919. Six courtyards remain and their 27 rooms house a museum. The front rooms are gorgeous with tiled half walls, terracotta designs and wonderful ceilings and moldings. The front exterior and minarets have dazzling tile work.

Jami Mosque Museum. Built in 1812, it is Kokand’s most impressive mosque. The 100m-long portico has 98 red-wood columns brought from India. The whole complex has been converted to a museum.

Narbutabey Mosque and Madrassa. Built in 1799, it is now closed as a madrassa. The kid from the hostel wanted to exchange money with his father so he accompanied to the last two places and had them opened up so I could visit.

Uzbekistan is very cheap; city buses10¢, cheeseburger $1, coffee 10¢, taxi across town 80¢, coke 50¢, share taxi 4 hours to Tashkent $5, gas 45¢/l.

Uzbeks seem friendlier than the rest of Central Asia. While I was waiting for my hotel registration slip, at least 8 guys wanted to talk. None had ever traveled outside Uzbekistan and few had been past Tashkent.

When you get gas, passengers must leave the vehicle and stay outside a fence. Passports must be registered frequently on highways. They always know where you are.

I exchanged $100, got 96- 500som bills, a huge wad, but this turned out to be a bad deal.

I stayed in Kokand for only one night and took a taxi to the ‘Tashkent taxi stand”. Every taxi with arriving travellers is mobbed by at least 10 guys courting your business. There were at least 50 waiting to fill their small cars as many are on their way to Tashkent for work. With all the competition, cars fill slowly and it can be a long wait. The road goes over a high pass that buses aren’t allowed to take so these share taxi’s are the only way to go.

TASHKENT (pop 2.2 million)

This is Central Asia’s hub. It’s one part newly built national capital and one part leafy Soviet city and another part sleepy Uzbek old town. It doesn’t always easily charm visitors.

Tashkent (pop 2.2 million)

History. The first people here were the Ming-Uruk in the 2nd century BC. By the time the Arabs took it in 751, it was a major caravan crossroads. It was given the name Tashkent “City of Stone’ in Turkic, in the 11th century. The Khorezmshahs, one of the ruling dynasties of Central Asia and Persia controlled it from the late 11th to the early 13th century until Chinggis Khan stubbed it out in the early 13th century, although it slowly recovered under the Mongols and then under Timur and grew more prosperous under the Shaybunids, the founding dynasty of what effectively became modern Uzbekistan, ruling from the mid 15th until the start of the 17th century.

The khan of Kokand annexed Tashkent in 1809 and then the Russians took it, despite being outnumbered 15 to one. They found a proud town, enclosed by a 25km-long wall with 11 gates of which not a trace remains today.

It became the main centre for the tsar’s and then Soviet’s espionage in Asia, during the protracted imperial rivalry with Britain known as the Great Game.

It became the capital of the Turkestan SSR in 1918 and again of the Uzbekistan SSR.

On April 25, 1968 a massive earthquake levelled vast areas of the town and left 300,000 homeless. The current look dates from the 1050s and 1960s. A slew of post-independence buildings have been built since independence in 1991.

In 1999, six bombs planted by Islamic militants killed 16 and injured 120.

I stayed at the very good Top-Chan hostel – possibly one of the best I have ever stayed in (59,000som/night) – great staff, kitchen, beds, breakfast, wi-fi. There were two Brits here cycling from England to Australia – both going crazy trying to get onward visas. The woman had been on the road alone for 8½ months.

Tashkent is short on good tourism sites. The new part of town has many nice parks full of people walking around.

Assumption Cathedral. Has a handsome gold onion dome and 50m bell tower. Is the biggest of 4 Orthodox churches in Tashkent. I watched a service – many gold robe priests with long hair and beards, much chanting and chest crossing.

Statue of Timur. It has lost its penis but not its balls.

Dom Forum. Holds state sponsored events for honoured guests. Closed to visitors.

Romanov Palace. A very cute tsarist edifice. Closed to public.

Senate. A grand modern building, one of many in Tashkent.

Independence Square. Has multiple arches covered with pelicans.

Crying Mother Monument. Honours the 400,000 Uzbek soldiers who died in WWII. Has an eternal flame. Very nice.

Sheikhantour Mausoleum Complex and Kaldirgochby Mausoleum. Have beautifully carved wooden doors and nice tile work. Closed to entry.

Kulkedash Madrassa. Built and the 16th century and closed by the Soviets (the only madrassa in all Central Asia open then was in Bukhara), it has lovely tile work adorning the brick exterior. Boys aged 16-20 attend. Dorms on the top floor and classes on the bottom surround a lovely courtyard. I was given a good tour.

Juma (Friday) Mosque. Built in the 1990s on the site of a 16th century mosque destroyed by the Soviets, it is very plain on the outside but very nice on the inside with 3 lavishly decorated domes with chandeliers.

Chorsu Bazaar. This is Tashkent’s most famous farmer’s market, capped by a giant green dome. If it grows and is edible, it is here. It is also the best place to change money on the black market. They offer less but it doesn’t take much bargaining to get 5700 to the US$. I basically lost $18 on my first exchange in Kokand. Even with 5000 som notes, it is large wad of cash.

Tashkent Metro. I did a lot of walking to get to the bazaar in the NW part of the city and took the metro home. For 20¢, it took me almost 3 hours to visit 23 (all but 3) Metro stations on the older three-line system. All are different, have marble interiors and floors and most have large-tile mosaics. Some have round roofs and some flat roofs supported by wonderful marble columns with capitals, many with spectacular lights and brass chandeliers with a huge variety of glass. Almost all have some wonderful feature. The Lonely Planet’s favourite was Kosmonavtlar (12 round paintings of space history from Icarus to Amir Timur’s astronomer grandson to many space firsts; man (Yuri Gagarin), woman, machine left on the moon, mapped the sky, rocket, first Uzbek, joint Russian/US etc). I asked a guy if he would interpret all the Uzbek Cyrillic and he even spoke good English.

My favourite was easily Chilonzor near the end of the red line – huge round brass chandeliers topped with great glass globes and 16 wonderful bas-relief murals.

Nothing compares with the Moscow metro stations but this may be the best thing to see in Tashkent. It was also a good way to meet locals and several talked to me.

Some observations on Uzbekistan.

Throughout Central Asia, dental care is poor and a preponderance of people have a mouth full of gold crowns. Central Asian men have a vigorous hand shake – the arm is raised and hands brought together almost with a slap, the other is grasped, hugs given and often cheeks touched. They look like they honestly want to meet and talk to their friend.

GM has a plant in Tashkent and an amazing number of cars are white Chevs. Uzbeks are poor drivers (nothing like the rally drivers of Tajikistan) and accidents and fatalities high. Unlike Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, there are few Russians but everyone speaks Russian. Headscarves are very common on women but Islam is not actively practiced. The kid from the hotel in Kokand never went to Mosque and a very modified form of ‘social’ Islam is practiced. Many drink alcohol and smoke cigarettes. The ability to ask directions from a map is negligible. Even taxi drivers can’t figure out where they are or how to get where you need to go from any map. Many think Canada is a state in the US. If you mention Canada, the first city they ask about is Ottawa and many mention hockey. The cheapest way to get around any city is to hitchhike. Money is expected and many men drive around picking people up. The fares are ridiculously low but gas is cheap. Every restaurant has jugs of water outside to wash your hands – and everyone does. Many toilets are squat-type – much more efficient than our raised sit toilets. It is how man had a BM since forever. The position forces the rectum to straighten at the bottom. hemorrhoids are a ‘Western’ affliction, induced by sit toilets.

Turkmenistan visa. I had hoped to receive the email notification for my Turkmenistan visa on Monday, November 9th. This is one of the least-tourist-friendly countries in the world. Even if you get the 5-day transit visa, most can’t use it as it is date-specific and often takes 2 weeks to get. The gave none out in October because of military exercises. Trying to time everything when getting visas on the road can be exasperating at best. If I was smart, I would have applied in Bishkek. So rather than being held hostage to this asshole country, and as I only had 8 days left on my Uzbek visa, I left on Tuesday morning to see the rest of Uzbekistan. Even if the notification had arrived, the visa takes all day to get: arrive between 6 and 7am to get an appointment to leave your passport, return to leave it, go across town to a bank to pay and then return again at 4 to pick it up – that is if they decide to cooperate. I planned on doing a whirlwind tour of the rest of the country, get my emailed pin and get the visa at the Turkmenistan border. If everything works, I will leave on the last day of my Uzbek visa with only 3 days to transit Turkmenistan.

I was up at 5am, packed, had breakfast, got my registration card and paid. I left the hostel at 7:25 and was in my seat in 17 minutes for the bullet train at 8am (230kms/hour, 2 hours and 10 minutes) SW to Samarkand. It is an uninteresting ride though flat land with bush and cotton.

SAMARKAND (pop 597,000, elev 710m)

Uzbekistan’s most glorious city and one of the most evocative Silk Road places, the sublime monuments to Timur are surrounded by a sprawling, modern, Soviet-built city.

History. Founded in the 5th century BC, it was the cosmopolitan, walled capital of the Soglian Empire when taken in 329BC by Alexander the Great. A key Silk Road city, it sits on the crossroads leading to China, India and Persia. More populous between the 6th and 13th centuries even than today, it changed hands every few centuries – Western Turks, Arabs, Persian Samanids, Karakhanids, Seljug Turks, Mongolian Karakitay, and Khoremshah – before being obliterated by Chinggis Khan in 1220. In 1370, Timur made it his capital and over the next 35 years, forged a new, almost mythical city – Central Asia’s economic and cultural epicenter. His grandson, Ulugbek, ruled until 1449 and made it an intellectual center as well.

When the Uzbek Shaybanids moved their capital to Bukhara in the 16th century, Samarkand declined, and after a series of earthquakes in the 18th century, it was virtually uninhabited. It was only truly resuscitated by the Russians who took control in 1868 and linked it to the Trans-Caspian railway in 1888.

After arriving, I caught a taxi to my hostel, Emir B&B. I paid in som and she charged me 5800 so to the $! This is not a rate anyone is getting. There was also a city tax of $2. Staying in a hotel/B&B is so much less rewarding than a hostel. You meet no one, there was no hot water and the room had no windows so was very stuffy.

So after leaving Tashkent at 8, I was out seeing the sites at 11am. And I saw everything in Samarkand in 6 hours walking everywhere. The tile work on all the buildings in Samarkand is nothing short of marvelous. All the prices quoted in LP are dated and all have kept pace with inflation and the black market value of the som.

Gur-E-Amir Mausoleum. This is the burial site of Timur, his two sons (Shah Rukh, the father of Ulugbek and Miran Shah), his two grandsons (including Ulugbek), Sheikh Seyid Umar (Timur’s most revered teacher). Timur died of pneumonia in 1405 (when the crypts was opened in 1941, Timur was tall for the era at 1.7m and lame in his right leg and arm from injuries suffered from a fall from a horse when he was 25 – thus Tamerlane or ‘Timur the lame’). The stones marking the graves are just markers – the actual crypts are in a chamber beneath. The building itself is grand with the typical over-the-top tile work. I wanted to pay in som and 6000 som to the $ was demanded.

Rukhobod Mausoleum. Dated 1370, this is the city’s oldest surviving monument, the burial site of one of Timur’s teachers, his two sisters and 10 children.

The Registan. This is an ensemble of three amazing madrassas surrounding a square – huge, all an overload of majolica tile, azure mosaics, minarets and domes. It is the centrepiece of the city and arguably the most awesome single sight in Central Asia. They are the world’s oldest preserved madrassas as anything older was destroyed by Chinggis Khan. They were in a significant state of disrepair at the start of the 20th century and were restored by the Soviets.

All the dormitories and classrooms now contain art and souvenir shops. The 15,700 som admission is good all day.

1. Ulugbek Madrassa. Finished in 1420, Ulugbek taught mathematics here.

2. Sher Dor (Lion Madrassa). Finished in 1636, it has roaring tigers in tile on the outer side flouting the Islamic prohibition against the depiction of animal.

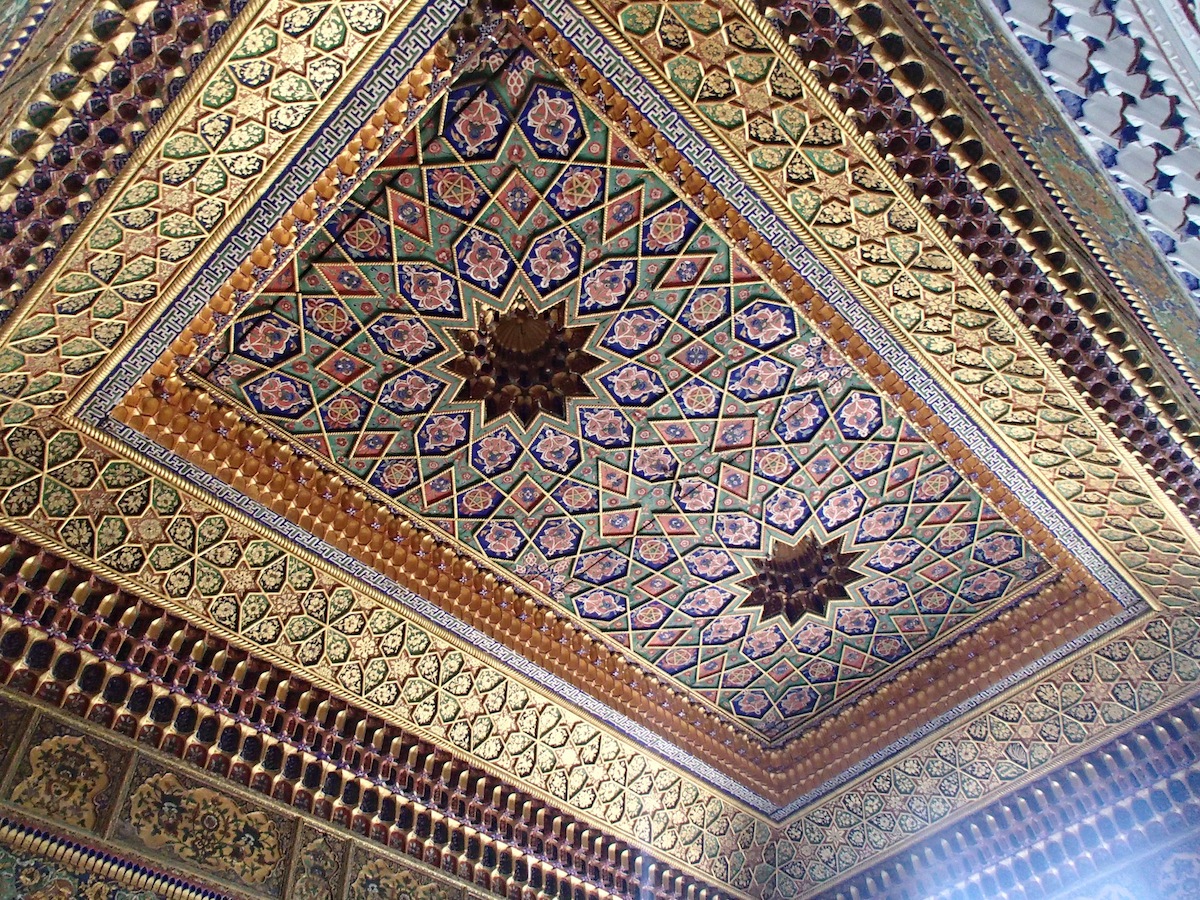

3. Tilla-Kari (Gold Covered) Madrassa. Completed in 1660, the highlight is the mosque, intricately decorated with gold. The mosque’s ceiling, oozing gold leaf, is flat but amazingly looks domed from the inside because of its tapered design. There is a good gallery of black-and –white photographs.

Old Town. This has been sealed off from tourist’s view by rerouting roads and building walls to close off virtually all access points. Find the gate of Toshkent street to enter the authentic neighbourhood. Like all Muslim neighbourhoods (think Seville, Cordoba and Grenada in Spain), they are a maze of streets where it is easy to get turned around in. I found the Makdumi Khorezm Mosque (not open), Koroboy Oksokol Mosque (behind a teahouse and meeting area for many of the residents of Old Town), and Mubarak Mosque, but could not locate the 1891 Gumbaz Synagogue after knocking on many doors – nobody had even heard of it (apparently still working with a decreasing 50 Jews in Samarkand).

Bibi-Khanym Mosque. This enormous building was finished just before Timur’s death and must have been the jewel of his empire. Once one of the world’s biggest Mosques, the cupola is 41m high and the entrance pishtak 38m.

It pushed contemporary construction techniques to the limit. Bibi-Khanym was Timur’s Chinese wife, ordered the mosque built as a surprise while he was away. The architect fell madly in love with her, was executed and Timur decreed that women henceforth wear veils so as to not tempt other men.

The mosque partially collapsed in an earthquake in 1897, was restored in 1970 and is badly in need of further work now. The interior courtyard contains a huge marble Quran stand.

Bibi-Khanym Mausoleum. A 14th century mausoleum for Timur’s Chinese wife across the street.

Slob Bazaar. A great collection of food and everything else.

Hazrat-Hizr Mosque. The 8th century mosque was burnt to the ground by Chinggis Khan and not rebuilt until 1854. It is Samarkand’s most beautiful mosque. When I was there, a young man came in and sang a song.

Afrosiab Museum. This is centred around a chipped 7th century fresco discovered in 1965. But the rest of the museum is missable and a walk. The woman in the museum refused to turn on the lights in the dark room containing the fresco, but I persisted. You could barely see anything without them.

Tomb of the Old Testament Prophet Daniel. This is a long walk north of the museum and not worth the effort, no less the ticket price. The sarcophagus is an improbable 18m long – legend has it that Daniel’s body grows by half an inch a year. His remains which date from at least the 5th century BC, were brought here by Timur from Susa, Iran (which also has a tomb of Daniel). The sarcophagus was covered with a cloth. The tomb is in a nice location under some cliffs in a park along the river.

Jewish Cemetery. From the Tomb of Daniel, I walked around the 2 sq. km dirt hill (early Samarkand) and entered this cemetery from the east. Most of the grave markers had lifelike etchings of the person on the black markers. I want one of these – they give a very personal touch to a cemetery.

Shah-I-Zinda. This is a stunning avenue of about 10 mausoleums containing some of the best tile work in the Muslim World. Originally the site of a shrine to Qusam, a cousin to the Prophet Mohammed said to have brought Islam to this area in the 7th century. It was ransacked by the Mongols and assumed its current form under Timur and Ulugbek who buried their family and favourites here.

.jpg)

At the end of the path between the mausoleums, the complex opens up into Samarkand’s main cemetery, a fascinating place to walk.

I took the bus 4 1/2 hrs to Bukhara. Half the price of a share taxi, they are also almost twice as long. The recently cultivated fields had anemic, pale grey soil that looked depleted of all nutrients.

BUKHARA (pop 263,000)

Central Asia’s holiest city, it has 1000 year old buildings, and a thoroughly lived-in old centre that hasn’t changed much in 2 centuries. Most of the centre is an architectural preserve, full of madrassas, minarets, a massive royal fortress and the remnants of a once-vast market complex.

Until a century ago, Bukhara had a network of canals and 200 stone pools, but the water wasn’t changed often and Bukhara was famous for plagues; the average Bukharan died by the age of 32. The Bolsheviks modernized the system and drained the pools.

History. It was the capital of the Samanid empire in the 9th and 10th centuries when it became Central Asia’s religious and cultural heart. It succumbed in 1220 to Chinggis Khan and in 1370 to Timur. In the 16th century, it was the capital of a khanate with a vast marketplace with dozens of specialist bazaars and caravanserais, more than 100 madrassas with 10,000 students and more than 300 mosques. The Mangit dynasty ruled from 1753 with a few depraved rulers including Nasrullah Khan (also called the ‘Butcher’) who ascended the throne by killing all his brothers and 28 relatives.

The Russians arrived in 1868. In 1918, a mob slaughtered a Russian delegation but they recaptured it soon after.

I took the bus 4 ½ hours from Samarkand and arrived at my hostel (Rumi) at 2pm to start sightseeing. It is in a family home where both children speak excellent English. Both are polyglots and took linguistics at university.

Char Minar. A gatehouse of a long-gone madrassa, its 4 domed towers make it very photogenic (it is the cover of Lonely Planet – Central Asia).

Kukeldash Madrassa. When built-in 1569, it was Central Asia’s larges madrassa. I went into one of the embroidery stores and became fascinated by suzannis. Made with cotton or silk, they are true works of art. They are a cottage industry centred in the home and take months to do the larger ones. Their cost barely reflects the amount of work that has gone into them. There are few tourists now and the stores are eager to make a deal.

Nadir Divanbegi Madrassa. It has stunning exterior tile work with a pair of peacocks holding lambs and a sun with a human face, in direct contravention of the Islamic prohibition against depicting living creatures.

Hoja Nasruddin. A statue of a semi-mythical ‘wise fool’ common in Sufi teaching tales.

Lyabi-Haus. This is a plaza built around a pool in 1620. It is the most peaceful and interesting spot in town and is shaded by mulberry trees as old as the pool.

Maghoki-Attar. This is Central Asia’s oldest surviving mosque. Under it were found a 5th century Zorastrian temple and an earlier Buddhist temple. It survived the Mongols by being buried in sand and only the top was visible in 1930. The present plaza surrounding it is the 12th century level of the town. The basement serves as a Museum of Oriental Carpets.

Covered Bazaars. These 3 domed bazaars are a masterpiece of brick work.

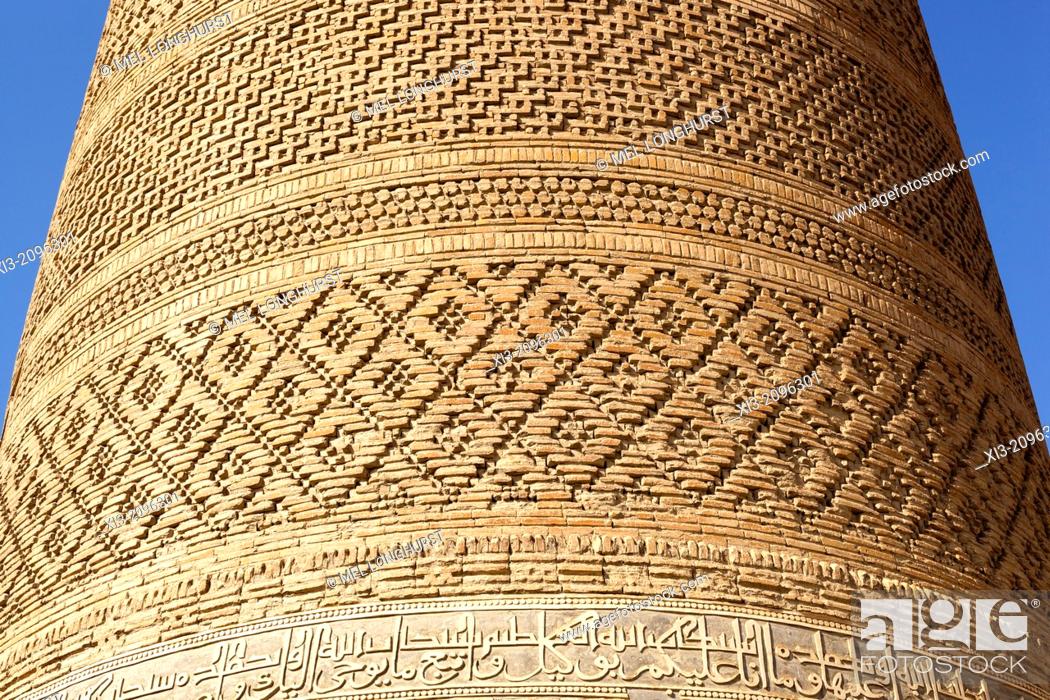

Kalon Minaret. Built in 1127, it was the tallest structure in Central Asia at 47m tall. It is an incredible piece of work with 10m deep foundations (includes reeds in an early form of earthquake proofing). Chinggis Khan was so dumbfounded by it that he ordered it spared. Its 14 ornamental bands, all different, were the first to use glazed blue tiles that were to saturate Central Asia under Timur. Its 105 stairs are closed to tourists.

Kalon Mosque. This 16th century mosque can hold 10,000. Its courtyard has spectacular tile work. The terracotta work on the outside had swastikas,, an ancient symbol in many religions.

Mir-i-Arab Madrassa. This huge still functioning madrassa has luminous blue domes in sharp contrast to the surrounding brown. Tourists are usually not allowed in.

Silk Carpet Factory. We went for a walk with the family who owned the hostel and had a tour of this amazing factory. 28 women work on looms in this unbelievably labour intensive craft. A 2x3m carpet takes 2½ years to make as two women produce 1 centimetre of carpet in one working day. The waft has two threads and each naturally dyed silk thread is knotted around each. I went the next day when the women were working. All were young and after age 35 are too old to continue as it is so hard on their back. One woman invited me to sit next to her. An intricate pattern is followed to knot each thread and cut it, then each row is aggressively combed tight and then the whole row is cut with scissors. I don’t particularly like the designs I saw, but they would be a lifelong possession.

Bahoutdin Architectural Complex. Shaykh Baha-ud-Din or Bohoutdin was the founder of the Naqshbandi order, and was considered the spiritual patron of Bukhara governors; he died in 1389. His necropolis remains the most esteemed in Uzbekistan.

Ismail Samani Mausoleum. Completed in 905, this is the town’s oldest Muslim monument and with 2m thick walls, its sturdiest architecturally. The outside is intricate baked terracotta brickwork. Behind are 2kms of the original 12km of eroded town walls.

Chashma Auub Mausoeum. Built in the 12 century, it has a peculiar cone-shaped dome and a spring inside that still has water.

Stolen tile discovered in London

Hoy Zayniddin Mosque. A still working mosque, it has some of the best original mosaic work in town.

Ark. This is Bukhara’s oldest structure occupied from the 5th century up to 1920 when it was bombed by the Red Army. It is a massive fortress with 20m walls, but most is a ruin. The occupied west end contains an active Juma (Friday) mosque and a bunch of museums.

Ulugbek Madrassa. Built in 1417, it is Central Asia’s oldest Madrassa. Like most things here, it is blue tiled and unrestored.

Abdul Aziz Khan Madrassa. This 16th century unrestored gem has as its highlight a prayer room with jaw-dropping ghanch stalactites dripping from the ceiling. This is muqarnas or the vaulted ceilings of honeycombed arches.

I ended up seeing almost all the monuments in Bukhara and then started the process of buying a suzani, one of the embroidered silk on silk hooked hangings. I had picked out a 3x2m embroidery of a caravan scene amid the colourful geometric/flower/fruit design. Originally the background silk is white but most are boiled in onions to give them a lovely gold hue. Originally $480, I paid $430 including the certificate (all craft work has to be certified to not be an antiquity) and postage home to Canada. For all the labour involved in these masterpieces, they would be worth thousands in Canada. But this was a cash price so I needed to find $250US somewhere. The banking system in Uzbekistan must be the most regimented, rule-laden, inefficient in the world. There is only one ATM in town and it rejected my card. The young guy from the hostel offered to help get cash. We went to several banks (all close for lunch between 2-3pm and then are only open till 3:30), you show your passport to get in and then your card is put into a standard chip card reader to get your cash. My MC and Visa credit and debit cards were rejected repetitively. So we were rushing around in taxis between banks all over town. I never did get any cash, went back to the store, and he found a business that had an old-fashioned swipe machine that was signed and did not need a pin. Then we went to the certificate office that also mails the parcel (I included a heavy fleece I didn’t need and the small embroidery I had purchased in Samarkand) and the deal was done. I plan on hanging it on a wall at home. It will be the showpiece of my apartment.

The end of this story is sad. The box arrived at the post office at home where I was paying them to keep my mail for 6 months. I had not read that they don’t accept boxes in kept mail! Two notices were sent to my mail box to pick up the box. It was eventually returned to sender. I contacted a travel agent in Bukhara who found the store where I purchased the suzani but it had never reappeared there.

I stayed in Bukhara two nights and then took a share taxi (80,000som), 450kms and 7 hours NW to Khiva, the last great monumental town in Uzbekistan. We traveled across the flat, bleak Kyzylkum Desert full of sand and sage to Urgench (pop 140,000). When the Amu-Darya River changed course in the 16th century, the people of Konye-Urghench 150 miles downriver in present Turkmenistan, were left without water and started a new town here. It’s mainly a transport hub for Khiva, 35kms southwest.

KHIVA (pop 50,000)

This Silk Road old town has a well-preserved historic centre and is dubbed the ‘museum city’ enclosed in majestic walls.

History. A minor fort and trading centre in the 8th century, its time came when Timur finished off Konye-Urgench. The Uzbek Shaybands moved in in the 16th century and Khiva was made the capital of Khorezm in 1592. The town ran a busy slave market raided from the Karakum Desert or Kazakh tribes of the steppes.

The Russians arrived in 1717 but the Khivans annihilated them. In 1740, Khiva was wrecked by a Persian. By the end of the 18th century it was rebuilt with the biggest slave market in Central Asia augmented by Russians. In 1873, a 13,000 strong Russian army invaded and massacred the townsfolk and took the khans silver throne to Russia. In 1924 it was absorbed into the new Uzbek SSR.

The old town is enclosed in a 2.5km long wall dating from the 18th century accessed by 4 gates. One ticket covers all the sites. Besides all the main sites below, the walls are filled with an old town that all looks thoroughly old.

Kuhna Ark. This is the Khiva ruler’s own fortress and residence inside the walls. First built in the 10th century, it was expanded in the 17th and includes his harem, mint, stables, arsenal, barracks, mosque and jail. The watchtower is part of the original Ark set against the massive west wall and offers great city views.

Mohammed Rakhim Khan Madrassa. Named after the khan who surrendered to the Russians, it now contains a museum.

Kalta Minor Minaret. Started in 1853 but never finished, this beautifully tiled minaret is still majestic and the iconic building in Khiva.

Sayid Alauddin Mausoleum. Dates to 1310 when Khiva was under the Golden Horde of the Mongol empire.

Juma Mosque. It has 218 wooden columns supporting the roof with 7 from the original 10th century mosque.

Juma Minaret. 47m high.

Tosh-hovlu Palace. The interior has ceramic tiles, carved stone and wood and 150 rooms off 9 courtyards.

Islom Hoja Madrassa and Minaret. Built in 1910, the minaret is Uzbekistan’s highest at 57m.

Pahiavon Mahumud Mausoleum. Khiva’s patron saint, poet, philosopher and legendary wrestler, the 1326 tomb has a turquoise dome and lovely tiling on the sarcophagus.

I stayed at Hostel Atabek, the home of a lovely family with great English. Also in the hostel were 4 young Japanese tourists all traveling separately. The breakfast was the biggest and best I have ever had.

Some More Observations on Uzbekistan

Cars run on either natural gas, called methane here, or benzene. The methane stations called Metan are surrounded by wrought iron fences with gates – passengers aren’t allowed inside and all stations have a ‘bazaar’ area usually a simple wood frame covered in sheet plastic to wait for the fill up. I imagine it is this way because of the extreme flammability of natural gas. The trunk of every car has a large tank for the methane.

As I have already said, the drivers are crazy – high speed on mediocre pot-holed roads, no seat belts, talking on their cell phones often, following amazingly close and passing frequently on hills. The music is always on. The safety of trains and buses is appealing. Speed traps are frequent and many drive with a radar detector.

Donkeys pulling carts are common even in downtown Tashkent. They are the beast of burden.

The money system creates some bizarre situations. If you can find the rare ATMs, they usually don’t work and if they do, have no money in them. Why would you want to give away 60% of the money you withdraw. With the highest denomination the 5000som note worth about 83¢, and by far the commonest denomination a 1000som note, you get huge wads of cash. Money changers for exchanging on the black market most commonly are at the bazaars but are common everywhere. Because of the significant inflation rate, the exchange rate changes almost daily. So it is necessary to enter the country with all the money you will need, in Euros or dollars. It is almost impossible to get cash anywhere. Uzbeks are the most efficient money counters in the world. Paying for a 10$ of groceries (which is a lot of groceries) involves counting 60 bills if using 1000som notes.

Eating sunflower seeds is a national pastime and cracking them an art form – women sitting in stores and bazaars, drivers and everyone else. After one 7-hour trip, our driver had a pile 6 inches high on the floor at his feet.

The cotton has all been picked by November, but now they are pulling up the spindly meter high plants by hand. They are then bundled and hauled away. I have no idea what they would be used for. Orchards of fruit trees are especially common around Samarkand. Other vegetables and potatoes, you never seen wheat or other grains being cultivated.

KARAKALPAKSTAN

This area comprises the western part of the country north of Nukus. If you like desolation, you will like it here. Of the 1.2 million people living in the entire area, only 400,000 are native Karakalpakstans. Formerly nomadic and fishing people, Soviet collectivization did a big hit on their culture. The destruction of the Aral Sea has rendered it one of Uzbekistan’s most depressed regions. The capital, Nukus seems half deserted, most towns are dying and the landscape blighted. Ironically, cotton, the crop that devastated the Aral, is now one of the main industries. State workers and children are forced into the fields at harvest.

One benefit of the Aral disappearance is the large oil and gas reserves under its dried-up bed. But most benefit goes to its Chinese investors and their Tashkent-based patrons.

NUKUS (pop 260,000)

Even though it attracts few tourists, there are some reasons to come.

Savitsky Museum. This holds one of the most remarkable art collections of the former Soviet Union. The museum owns some 90,000 artifacts and pieces of art, including 15,000 paintings, half brought here in Soviet times by renegade artist and ethnographic Igor Savitsky. Elsewhere in the USSR, most art was destroyed for not conforming to the socialist realism of the times. The paintings found protection in these isolated backwaters – Nukus it literally the last place you’d look for anything.

Moynaq (pop 12,000). 210kms north of Nukus, it was once one of the Aral Sea’s two major fishing ports, but now sits over 200kms from the nearest shore of the lake. Now a virtual ghost town, the only real reason to come here is to see the remains of the fishing fleet now rusting on the sand. Summers are hotter, winters colder and the debilitating dust storms make life unpleasant at best.

Aral Sea. Trips to see actual water require knowledgeable drivers. Oil refineries belch smoke and fire and then a part of the sea bed is crossed that has been dry for so long that there is a forest of sage brush before reaching salt flats and after about 5 hours of driving, actual water. To swim requires wading through about 50m of knee-deep muck. The water is so salty, it will suspend a brick.

Life is falling apart.

Since losing my wallet – pickpockets are magicians – things are getting frustrating. The pins on my two credit cards have been rejected for some unknown reason, but I can still book online.

I arrived in Nukus, bargained down the price of the hotel from 150,000som to 110,000 ($18.50) and got the news that the only real attraction in Nukus, the Savitsky Museum, has just closed for the day and is closed on Mondays, tomorrow. I Skyped Mastercard for the 10th or so time to arrange the cash advance, but got dropped several times. I had spent $8 of my dwindling Skype balance and must have used it for hours (the cost of a phone calls would have been in the hundreds of dollars). For whatever reason, I could not add money to Skype. It was now almost 48 hours since I first talked to MC and after many promises of the impending money arriving at a Western Union, it seems no nearer to happening. After the hotel and dinner, I am down to US$150, possibly not enough to go to Turkmenistan even if I got the visa. Buying an expensive embroidery now looks kind of foolish.

So I decided to fly from Nukus to Tashkent on the 16th and onto Dubai on the 17th, the last day of my Uzbekistan visa. There are severe penalties for overstaying one’s visa (from jail to thousands of dollars of fines – who knows what story is correct?). I tried for hours to book flights using my MC but the securicard screen (for online bookings) would never show.

Train schedules showed a few possibilities to get to Tashkent, a 20-hour journey. A train from Nukus arrived an hour after my hoped for flight departed. So I drove back to Urgench ($3.50) for a 3:30pm train that arrived at 10:20am on the 17th, lots of time for the flight and to deal with any problems. I changed some money to buy the train ticket; the overnight journey was 113,000som ($19) and saved a night in a hotel. I didn’t have anything else to do anyway. Long distance travel is unbelievably cheap at about 1$/hour.

I have a delusional optimism that things would work out. And after 3 days of very cold, windy, rainy weather, the sun was shining with bright blue skies. MC offers a remote pin reset but would require wi-fi in the Tashkent airport and my Skype balance was dwindling.

I used the very posh VIP lounge in the Urgench Rail Station (fee 33¢!), and bought some groceries for the trip – the 2 tomatoes, 2 bananas, litre of milk, pack of smokes and large chocolate bar came to $3.20 – few countries are as cheap as Uzbekistan. Back in the lounge, I put on my flip flops (god I hate shoes), reorganized my pack, watched TV and charged my computer. Things were looking up.

I love trains. They are so civilized – you can move around, have a bathroom (although usually foul squat toilets), comfortable seating, a bed, electricity, all the hot water you want, and the melodic rhythm of the rails. One negative is that the compartments can get very hot and stuffy.

I had never been on a train until I worked as a brakeman for the CPR as a summer job and then not again until I started to travel. And I have been on some great trains: the Trans Siberian, the spectacular Japanese system, the Chinese system rapidly approaching Japan’s, the chaotic Indian system and easily the worst trains in the world in Myanmar. North America is so far behind.

Of the 900kms to Tashkent, 400 goes through desert – endless sand and sage brush. The train was an older Soviet-style but nicely appointed inside and there are only two of us in the 4-bed compartment.

In Tashkent, I went to Top Chan Hostel to use the Internet and determine the status of my cards. Amazingly, after talking to MC frequently for 4 days, I learn that they had cancelled by credit card four days previously, with no explanation!! And then they tell be that the emergency cash had been available for the same 4 days!! What a bunch of nincompoops. No wonder I could book nothing. I then spent time finding out if my Visa card was working, find out it is fine, add Skype minutes and ask if they can get me emergency cash. They can’t do it for Uzbekistan and ask if it is possible for Kyrgyzstan, but they take an interminable amount of time, the call gets dropped several times and I give up. I had an excellent plov for lunch for 1$. Not everything is a disaster.

My Turkmenistan transit visa appeared by email while at Top Chan (15 days after applying for it), but it is the last day of my Uzbekistan visa and I am now in Tashkent, not Nukus where I must enter (the dates and entry/exit points must be adhered to). A flight back to Nukus arrived there at 8pm but the border closes at daylight making crossing impossible. If only I had gotten the notification 26 hours earlier.

Because of the uncertainty of whether I could transit the Almaty, Kazakhstan airport without a visa, I decided to go to Kyrgyzstan where it is a free visa. With uncertainties of booking a flight, I took a share taxi to Andijon in the Fergana Valley to cross at Osh hoping the border was open late. After the usual bargaining over price and waiting for the share taxi to fill, I was finally on my way at 2pm for the 6-hour drive.

I ended up with the slowest, most cautious driver in the country. I was told that the border closed at 8 but decided to try anyway, drove the 40km and arrived at a completely dark, obviously closed border. But a soldier was shining a flashlight so I went up to the gate and explained that my passport was expiring in 2½ hours. Amazingly he opened the gate and they processed me through Uzbekistan customs!! It was a very thorough search even going though many files in my computer. They hailed Kyrgyzstan customs, I waited for 15 minutes in the very dark “no-mans land” and got a Kyrgyz stamp! “You must never do this again. You woke me up. What present do you have for me?” I gave him a large (probably fake and heavy) piece of turquoise from Tibet that I didn’t really want anyway. There was even a taxi at the border and for the exorbitant price of 7$, got a ride into Osh. Someone was smiling down on me.

In Osh the streets were packed and apartments empty. There had been an earthquake but I finally dragged myself into bed at 1am at Osh GH. I was the only guest.