TANA TORAJA is an area best known for its peculiar fascination with the dead. Life for the Torajans revolves around death and their days are spent earning the money to send away their dead properly in elaborate, brutal and captivating funeral rites. During a funeral season in July and August, the tourist numbers swell and prices soar, but the rest of the year, it’s empty and starved for visitors.

With 9 million people, South Sulawesi has four ethnic groups, three of them Muslim, all in the lowlands. The 650,000 Christian Torajans live in the mountains and most are farmers. Another 2 million Torajans live around Indonesia (especially Papua and Kalimantan working in mining) and the world having left for education, business and jobs. Much of their income returns to Toraja.

Islam was introduced into South Sulawesi in the 14th and 15th centuries by traders from Gujarat, India but it did not reach mountainous Toraja. During a civil war in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Muslim South tried to force Islam on the Torajans, but they didn’t accept it and remained animist. In the early 20th century, Dutch missionaries tried to stop the sacrifices but they were killed. A second conversion attempt was more tolerant so that today Torajans practice a fusion of animism and Protestant Christianity. 90% of the people in Toraja are Christian, 9% Muslim and 1% animist (mostly in remote areas).

The local culture is among the world’s most unique and distinctive. That the people are genuinely welcoming of visitors makes it unmissable. Funerals are the area’s main tourist attraction.

The religious ceremony has two types of ritual. Life rituals occur around sunrise, use smoke (ascending), celebrate house raisings and harvest times and only chickens and pigs are sacrificed. The end of the rice harvest, from May onwards, is ceremony time in Toraja. Feasting, dancing, buffalo fights and sisemba kickboxing are the main activities. Death rituals are descending rituals (the body goes down), and are associated with funerals and pigs and water buffalo, but no chickens, are sacrificed.

Rantepao (pop 49,000, elevation 700-800m)

Makape is the capital of Toraja, but Rantepao is the largest town and tourist magnet serving as the best base for exploration. Pasar Bolu is a market 2km northeast of town that peaks every six days, overflowing with livestock. It is an unforgettable sight, a big, social occasion that draws crowds from all over Toraja.

The hotel owner found a guide who knew where there was a funeral. Arru’ (Arruan Tangdilintin – arruantangdilitin@yahoo.co.id – mobile: +6285299235999) turned out to be a great guy with superb English and a willingness to share the culture with strangers. For 380,000Rp ($30) including motorcycle and gas, we were going to a funeral on the day that guests were being received. We bought 10 packs of cigarettes as a gift to the family. The drive took 1½ hours over a circuitous route of pavement, broken pavement, rocky roads, mud, high clearance areas and then a kilometre walk to the village of Mila on the side of a mountain south of Rantepao.

Funeral. Several lavishly decorated temporary buildings had been constructed for funeral guests around the family house. Four water buffalo lay dead in front of the house with their throats slit, the blood soaking the ground.

A master of ceremonies made announcements over a loudspeaker and a professional videographer recorded the events. Family members shook my hand and posed for pictures. Different groups of guests and/or relatives filed into the receiving hall past all the great-grandchildren in bright traditional outfits. A funeral singer and flute player accompanied each group of guests and family. Gifts of betel nuts for the women and cigarettes for the men were distributed. Lines of serving girls brought in food for the guests. A big pig was carried by stretched out on a bamboo frame. People keep careful track of who brings what to ceremonies (gifts are announced to the funeral throngs over the loudspeaker) and an “offering” considered cheap is cause for shame. A water buffalo offering engenders the local joke uttered at funerals when the animal is sacrificed “There goes another Toyota”.

Arru’ and I were invited into a small separate room and I was introduced to the family of the 90-year-old woman whose funeral I was attending: her son and his wife, 5 of their 7 children and several great-grandchildren. I gave them the carton of cigarettes. Two of the sweetest 6 year-old-girls with eye makeup, traditional dresses and extravagant bead necklaces sat on my lap for pictures. One of the grandchildren (a 22-year-old beauty who had just graduated from university as a teacher) served coffee, tea and sweets while flirting with me. I fell in love.

Food consisting of rice and buffalo meat, pig blood and vegetable mixture cooked in a bamboo tube was served. I was treated like the guest of honour. Everyone was happy and having a good time. Many other family members came by to introduce themselves and shake hands. After the meal, everyone took turns taking pictures with me. It was all pleasantly surreal.

The water buffalo were skinned and butchered by professional butchers. Wheelbarrows carrying the sour, bright green contents of the rumen were dumped down the road. The pig was killed with a knife to the heart, butchered and some guys cooked the liver over a small open fire. All the meat was used for the guests today and then distributed throughout the community.

The dead person had died 11 months previously, was embalmed with modern methods and had been in the family house all this time. Visitors are expected to sit, chat and have coffee with them. During the 11 months, she was merely considered “sick” and only considered “dead” now that her funeral was taking place. The actual funeral happens 3 months to 2 years after death so that all the arrangements can be made. The temporary buildings had to be constructed, animals purchased for slaughter and family members spread all over Indonesia given time to make arrangements to come home.

The funeral itself occurs over 3-7 days depending on the social status of the dead person. This was a four-day affair.

Day 1 starts at sundown when the coffin is moved from the south to the west side of the house signifying death and one water buffalo is sacrificed.

Day 2 has a Christian funeral conducted by a priest in the church and buffalo fighting where pairs of bulls face off in an open field. A second water buffalo is sacrificed.

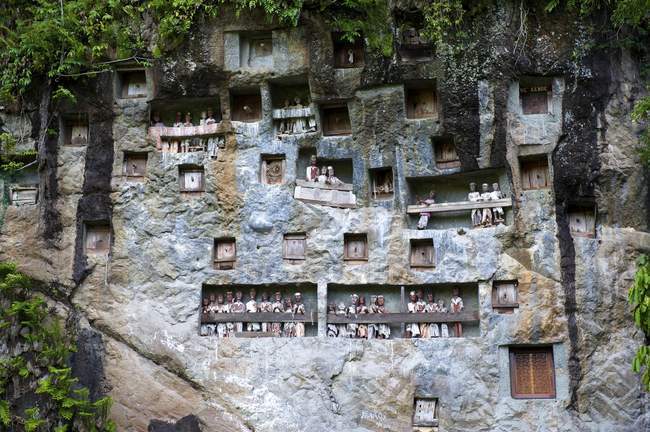

Day 3, the day I was there, is when guests are received, several buffalo (representing men) are sacrificed depending on social status, pigs (representing women) are sacrificed and everyone socializes and eats traditional food cooked in bamboo. The family receives pigs from family and friends and distributes gifts of money and kind to everyone attending. Day 4 is the actual burial day with a church service and interment by the method most suited to social status and family preference. Nowadays, noble people are buried in stone graves (large rooms chiselled into limestone cliff faces). Other well-off people are buried in family mausoleums and others are buried in rocky areas in above-ground graves. Practically, good land is not used for cemeteries. The funeral is licensed by the government and guests must sign an official register.

The whole process is all about cementing relationships – between family, friends of the family and fellow villagers. All donate to the funeral (pigs are the common commodity) and the family then incurs a debt that is paid off in kind in the future. Food is provided and meat is distributed amongst the whole community. Class standing is demonstrated by the generosity of the individual. Sacrificing animals is necessary to accompany the dead spirit to the afterlife, showing respect for the end of life. Children and grandchildren show respect for their parents and grandparents by sacrificing and participating in the ceremonies.

We left the funeral at about 2 pm and rode to a “baby grave”. This method of burial has not been used for 50 years and was only for babies without teeth. They were considered pure and holy and animal sacrifice was not part of their funeral. A hole was carved in a live tree on the side facing away from where the family lived and the baby was placed standing in the hole, the hole packed with palm leaves and covered with a palm leaf door. The belief was that the sap of the tree would nourish the baby like breast milk. Meanwhile, the wife who was never allowed to see the tree killed a pig and mourned with family and fellow villagers. The tree I saw had at least 15 baby burials on all its sides.

We then went to a cave burial site near the town of Londa. Caves were used in the 14th and 15th centuries. When a person died, they were “embalmed” using natural herbal methods, wrapped in cloth and remained in the family home for the next 10-20 years. By then, only the skeleton remained. The bones were then placed in family wood coffins in the shape of boats, buffalo or pigs, in caves. The coffins sat on wood frames suspended out from the walls. Higher-class people were placed in higher positions in the cave than lower-class people who were on the floor. Dressed wood effigies of the dead were in “balconies” lining the cave walls. Today some of the coffins have fallen and most are in a state of rot. Skulls and random bones were scattered in niches on the walls or on the floor depending on social class. After entering through a low tunnel, the side of the cave is open. I walked through the lower section out to fields with stone graves scattered across a cliff face. These were closed with cement and doors and are still being used today.

Gallery of ancestors

We then saw stone graves reserved for the nobility near the town of Lemo. On the way, we passed monolith fields – huge oddly shaped linear rocks stuck in the ground over an open area. This is where the funeral rituals of sacrifice occurred before the actual stone grave burial. Twenty-four buffalo were sacrificed for these high-ranking funerals. The graves themselves are large 10 cubic meter rooms carved into a towering, vertical limestone cliff closed with small doors. They are still used today and each room is reserved for one family. When the room is full of coffins, the doors are permanently sealed. Stone statues fill balconies cut into the cliff.

Above-ground graves line the base of the cliffs. A small building is full of coffins shaped like boats and water buffalo.

Beside above-ground graves, more well-off people are buried in elaborate mausoleums – small buildings with boat-shaped structures on top.

Funerals are very costly affairs for families. They sometimes save their entire lives for it. But they don’t bankrupt themselves. Torajans realize it is more important to educate their children properly to have successful lives and to continue future funeral ceremonies.