Iran – Fars (Shiraz) October 13-16, 2019

Day 3

After flying to Shiraz in the evening of day 2 (Oct 13), we checked into our hotel and left at 8am to see Persepolis. The 60km drive was across a flat plain set between barren yellow rocky mountains.

ACHAEMENID EMPIRE

The Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire based in Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great. Ranging at its greatest extent from the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper in the west to the Indus Valley in the east, it was larger than any previous empire in history, spanning 5.5 million square kilometers. Incorporating various peoples of different origins and faiths, it is notable for its successful model of a centralised, bureaucratic administration, for building infrastructure such as road systems and a postal system, the use of an official language across its territories, and the development of civil services and a large professional army. The empire’s successes inspired similar systems in later empires.

By the 7th century BC, the Persians had settled in the south-western portion of the Iranian Plateau in the region of Persis, which came to be their heartland. From this region, Cyrus the Great advanced to defeat the Medes, Lydia, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire, establishing the Achaemenid Empire. Alexander the Great, an avid admirer of Cyrus the Great, conquered most of the empire by 330 BC. Upon Alexander’s death, most of the empire’s former territory fell under the rule of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire, in addition to other minor territories which gained independence at that time. The Iranian elites of the central plateau reclaimed power by the second century BC under the Parthian Empire.

The Achaemenid Empire is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city-states during the Greco-Persian Wars and for the emancipation of the Jewish exiles in Babylon. The historical mark of the empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, technological and religious influences as well. Despite the lasting conflict between the two states, many Athenians adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange, some being employed by or allied to the Persian kings. The impact of Cyrus’s edict is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts, and the empire was instrumental in the spread of Zoroastrianism as far east as China. The empire also set the tone for the politics, heritage and history of Iran.

PERSEPOLIS was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BC). It is situated 60 km northeast of the city of Shiraz. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

The English word Persepolis means “the Persian city” or “the city of the Persians”. To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Pārsa, which is also the word for the region of Persia.

Geography. Persepolis is near the small river Pulvar, which flows into the Kur River. As is typical of Achaemenid cities, Persepolis was built on a (partially) artificial platform. The site includes a 125,000-square-meter terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of Rahmat Mountain. The other three sides are formed by retaining walls 5–13m on the west side with a double stair. From there, it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

History. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces. Persepolis probably became the capital of Persia proper during his reign. However, the city’s location in a remote and mountainous region made it an inconvenient residence for the rulers of the empire. The country’s true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This may be why the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

Darius I built Apadana, the Council Hall (Tripylon or the “Triple Gate”), the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire.

Grey limestone was the main building material used at Persepolis. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A deep elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain.

The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide a protected space for the defence personnel. The first wall was 7m tall, the second, 14m and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27m in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

The empire extended from India to Hungary and Greece in Europe and to Egypt in Africa. 28 “nations” were included and this is another recurring theme of the rock bas-relief carvings. One wall has representatives of each nation carrying gifts and animals, each getting their bas-relief. The tombs all have 28 men supporting the platform on which the king stood.

Function. The function of Persepolis remains rather unclear. It was not one of the largest cities in Persia, let alone the rest of the empire, but appears to have been a grand ceremonial complex, that was only occupied seasonally; it is still not entirely clear where the king’s private quarters were. Most archaeologists held that it was especially used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year, held at the spring equinox, and still an important annual festivity in modern Iran. The Iranian nobility and the tributary parts of the empire came to present gifts to the king, as represented in the stairway reliefs.

Destruction. After invading Achaemenid Persia in 330 BC, Alexander the Great sent the main force of his army to Persepolis by the Royal Road. He stormed the “Persian Gates”, a pass through the modern-day Zagros Mountains. There Ariobarzanes of Persis successfully ambushed Alexander the Great’s army, inflicting heavy casualties. After being held off for 30 days, Alexander the Great outflanked and destroyed the defenders. Ariobarzanes himself was killed either during the battle or during the retreat to Persepolis. Some sources indicate that the Persians were betrayed by a captured tribal chief who showed the Macedonians an alternate path that allowed them to outflank Ariobarzanes in a reversal of Thermopylae. After several months, Alexander allowed his troops to loot Persepolis.

Around that time, a fire burned the palaces. It is not clear if the fire was an accident or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It could be both an accident and a case of revenge.

The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century, describes Persepolis’ archives as containing “all the Avesta and Zend, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink”, which were destroyed.

Paradoxically, the event that destroyed these texts may have resulted in preserving the Persepolis Administrative Archives tablets by causing the collapse of the upper part of the northern fortification wall that preserved the tablets until their recovery. The fire hardened the clay tablets to preserve them. All 25,000 were taken to the University of Chicago and translated. They were primarily salary records of the 10,000 royal guards and other citizens. They showed that the women of the Achaemenid Empire had equal pay and maternity leave. Recently a portion of them were shown at the National Museum in Tehran for 2 months.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire. In 316 BC, Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire. The city gradually declined over time. The lower city at the foot of the imperial city might have survived for a longer time but the ruins of the Achaemenids remained as a witness to its ancient glory. In about 200 BC, the city of Estakhr, five kilometres north of Persepolis, was the seat of the local governors. From there, the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and Estakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sasanian kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighbourhood and in part even the Achaemenid ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions. The Romans knew as little about Estakhr as the Greeks had known about Persepolis, even though the Sasanians maintained relations for four hundred years, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Muslim invasion of Persia, Estakhr offered a desperate resistance. It was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis of Shiraz. In the 10th century, Estakhr dwindled to insignificance and over the following centuries, Estakhr ceased to exist as a city.

Archaeological research. Many travellers visited the ruins from 1320-1704 and even now it is, comparatively speaking, it is well cultivated. In 1881-82, 350 groundbreaking illustrations of Persepolis were provided by the French. The first scientific excavations at Persepolis were carried out by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt representing the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago from 1930-8.

Herzfeld believed that the reasons behind the construction of Persepolis were the need for a majestic atmosphere, a symbol for the empire, and to celebrate special events, especially the Nowruz. For historical reasons, Persepolis was built where the Achaemenid dynasty was founded, although it was not the center of the empire at that time.

Architecture. Persepolitan architecture is noted for its use of the Persian column, which was probably based on earlier wooden columns. Architects resorted to stone only when the largest cedars of Lebanon or teak trees of India did not fulfill the required sizes. Column bases and capitals were made of stone, even on wooden shafts, but the existence of wooden capitals is probable. In 518 BC, a large number of the most experienced engineers, architects, and artists from the four corners of the universe were summoned to engage and with participation, build the first building to be a symbol of universal unity and peace and equality for thousands of years.

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, the Palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.

Ruins and remains. Ruins of many colossal buildings exist on the terrace. All are constructed of dark grey marble. Fifteen of their pillars stand intact. Three more pillars have been re-erected since 1970. Several of the buildings were never finished.

So far, more than 30,000 inscriptions have been found from the exploration of Persepolis, which are small and concise in in size and text, but they are the most valuable documents of the Achaemenid period. Based on these inscriptions that are currently held in the United States most of the time indicate that during the time of Persepolis, wage earners were paid.

Persepolitan Stairway. Built in 519 BC, this broad dual stairway on the side of the Great Wall is the main entrance to the terrace 20m above. The 111 steps are 6.9m wide, with treads of .31m (12 inches) and rises of 10 centimetres (3.9 inches). Originally, the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback. New theories, however, suggest that the shallow risers allowed visiting dignitaries to maintain a regal appearance while ascending. The top of the stairways leads to the NE corner of the terrace, opposite the Gate of All Nations.

Gate of All Nations. The Gate of All Nations, referring to subjects of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was a square of approximately 25m in length, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall. There were two more doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other opened onto a long road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal.

A pair of lamassus, bulls with the heads of bearded men, stand by the western threshold. Another pair, with wings and a Persian Head, stands by the eastern entrance, to reflect the power of the empire.

The name of Xerxes I was written in three languages and carved on the entrances, informing everyone that he ordered it to be built.

The Apadana Palace. Darius I built the greatest palace at Persepolis on the western side of the platform. This palace was called the Apadana. The King of Kings used it for official audiences. The work began in 518 BC, and his son, Xerxes I, completed it 30 years later. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60m long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Each column is 19m high with a square Taurus (bull) and plinth. The columns carried the weight of the vast and heavy ceiling. The tops of the columns were made from animal sculptures such as two-headed lions, eagles, human beings and cows (cows were symbols of fertility and abundance in ancient Iran). The columns were joined to each other with the help of oak and cedar beams, which were brought from Lebanon. The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco to a depth of 5 cm, which was used for bonding, and then covered with the greenish stucco found throughout the palaces.

Foundation tablets of gold and silver were found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Palace. They contained an inscription by Darius in Old Persian cuneiform, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, and is known as the DPh inscription.

Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia, to Kush, and from Sind (“Indus valley”) to Lydia (Old Persian: “Spardâ”) – [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house! — DPh inscription of Darius I in the foundations of the Apadana Palace

At the western, northern and eastern sides of the palace, there were three rectangular porticos each of which had twelve columns in two rows of six. At the south of the grand hall, a series of rooms were built for storage. Two grand Persepolitan stairways were built, symmetrical to each other and connected to the stone foundations. To protect the roof from erosion, vertical drains were built through the brick walls. In the four corners of Apadana, facing outwards, four towers were built.

The walls were tiled and decorated with pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers. A recurring theme is a lion biting the back of a bull – this shows the start of spring. Zorastrian symbols of an eagle crown most of the other bas-reliefs. The king is often shown with servants holding elaborate umbrellas and using whisks to shoo away flies.

Darius ordered his name and the details of his empire to be written in gold and silver on plates, which were placed in covered stone boxes in the foundations under the Four Corners of the palace. Two Persepolitan style symmetrical stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of Apadana to compensate for a difference in level. Two other stairways stood in the middle of the building. The external front views of the palace were embossed with carvings of the Immortals, the Kings’ elite guards. The northern stairway was completed during the reign of Darius I, but the other stairway was completed much later.

The reliefs on the staircases allow one to observe the people from across the empire in their traditional dress, and even the king himself, “down to the smallest detail”.

Apadana Palace coin hoard. The Apadana hoard is a hoard of coins that were discovered in excavations in 1933 by Erich Schmidt under the stone boxes containing the foundation tablets of the Apadana Palace. Dated to circa 515 BCE. The coins consisted in eight gold lightweight Croeseids, a tetradrachm of Abdera, a stater of Aegina and three double-sigloi from Cyprus. The Croeseids were found in very fresh condition, confirming that they had been recently minted under Achaemenid rule.

The Throne Hall. Next to the Apadana, second largest building of the Terrace and the final edifices, is the Throne Hall (Imperial Army’s Hall of Honor, also called the Hundred-Columns Palace). This 70×70 square meter hall was started by Xerxes I and completed by his son Artaxerxes I by the end of the fifth century BC. Its eight stone doorways are decorated on the south and north with reliefs of throne scenes and on the east and west with scenes depicting the king in combat with monsters. Two colossal stone bulls flank the northern portico. The head of one of the bulls now resides in the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

At the beginning of the reign of Xerxes I, the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for military commanders and representatives of all the subject nations of the empire. Later, the Throne Hall served as an imperial museum.

Other palaces and structures. The Tachara, which was built under Darius I, and the Imperial treasury, which was started by Darius I in 510 BC and finished by Xerxes I in 480 BC. The Hadish Palace of Xerxes I occupies the highest level of terrace and stands on the living rock. It took 6 months for Alexander to empty the treasury and carry away all the loot on horses. The Council Hall, the Tryplion Hall, the Palaces of D, G, H, storerooms, stables and quarters, the unfinished gateway and a few miscellaneous structures at Persepolis are located near the south-east corner of the terrace, at the foot of the mountain.

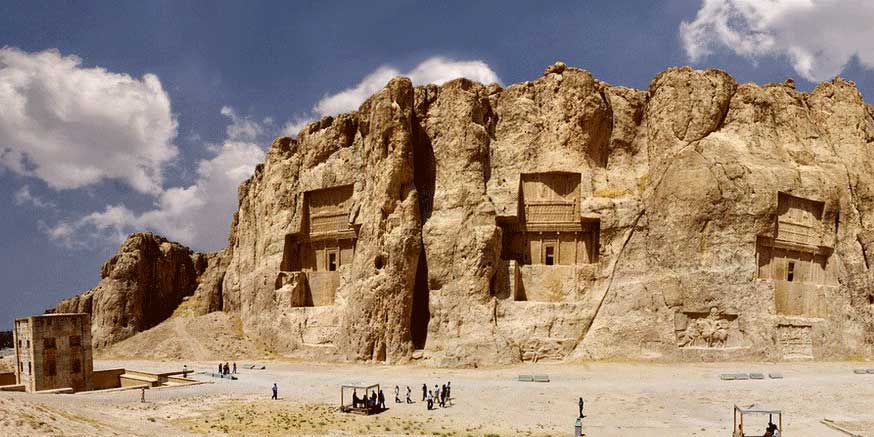

TOMBS. It was the custom for a king to prepare his own tomb during his lifetime. Cyrus the Great was buried in Pasargadae.

The kings buried at Naghsh-e Rostam are probably Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II. About 13 km NNE, on the opposite side of the Pulvar River, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. Modern-day Iranians call this place Naqsh-e Rustam (“Rustam Relief”), from the Sasanian reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. It may be inferred from the sculptures that the occupants of these seven tombs were kings. An inscription on one of the tombs declares it to be that of Darius I, concerning whom Ctesias relates that his grave was in the face of a rock, and could only be reached by the use of ropes. Ctesias mentions further, with regard to a number of Persian kings, either that their remains were brought “to the Persians,” or that they died there.

Behind the compound at Persepolis, there are three sepulchers hewn out of the rock in the hillside. The facades, one of which is incomplete, are richly decorated with reliefs.

The two completed graves behind the compound at Persepolis would then belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. That of Artaxerxes II is complete and the one we visited. Carved into the natural rock, the face has columns with horse capitals, 28 figures representing the 28 subject countries, the king facing a fire with the sun and the Zorastian symbol above. They buried only the bones of the deceased, no treasures and the tombs had been looted. It is not possible to enter the tomb. There are several platforms inside for the king, queen and their children.

Since Alexander the Great is said to have buried Darius III at Persepolis, then it is likely the unfinished tomb is his.

Museums (outside Iran) that display material from Persepolis. One bas-relief from Persepolis is in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England. The largest collection of reliefs is at the British Museum, sourced from multiple British travellers who worked in Iran in the nineteenth century. The Persepolis bull at the Oriental Institute is one of the university’s most prized treasures, part of the division of finds from the excavations of the 1930s. New York City’s Metropolitan Museum houses objects from Persepolis, as does the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of the University of Pennsylvania. The Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon and the Louvre of Paris hold objects from Persepolis as well. A bas-relief of a soldier that had been looted from the excavations in 1935-36 and later purchased by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts was repatriated to Iran in 2018, after being offered for sale in London and New York.

Nasqsh-e Rostam and Naqsh-e Rajab. Tentative WHS (22/05/1997)

About 13 km NNE of Persepolis, on the opposite side of the Pulvar River, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. Modern-day Iranians call this place Naqsh-e Rustam (“Rustam Relief”), from the Sasanian reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. An inscription on one of the tombs declares it to be that of Darius I, concerning whom Ctesias relates that his grave was in the face of a rock, and could only be reached by the use of ropes.

The kings buried at Naghsh-e Rostam are probably Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II in four large cross-shaped tombs cut into the cliff face. All have the same design: the 28 “nations” holding up the king, with a fire, sun and Zorastrian symbol on top. At one time they could be entered but are now closed to the public.

A Zorastrian cube sits out front. A simple marble square building with 4 stories, it has stairs up one side. It held perpetual fire.

The Sasarians carved great bas-reliefs on the bottom of the cliffs. The best is at the far end showing the king getting his ring of power from an angel. There is great detail in the carvings.

Day 4 Shiraz

SHIRAZ (pop 1,870,000)

Shiraz is the fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars Province (Old Persian as Pars). Shiraz is located in the southwest of Iran on the “Rudkhaneye Khoshk” (The Dry River) seasonal river. It has a moderate climate and has been a regional trade center for over a thousand years. Shiraz is one of the oldest cities of ancient Persia.

The earliest reference to the city, as Tiraziš, is on Elamite clay tablets dated to 2000 BC. The modern city was founded or restored by the Umayyads in 693 and grew prominent under the successive Iranian Saffarid and Buyid dynasties in the 9th and 10th–11th centuries, respectively. In the 13th century, Shiraz became a leading center of the arts and letters, due to the encouragement of its ruler and the presence of many Persian scholars and artists. It was the capital of Persia during the Zand dynasty from 1750 until 1800. Two famous poets of Iran, Hafez and Saadi, are from Shiraz, whose tombs are on the north side of the current city boundaries.

Shiraz is known as the city of poets, literature, wine (despite Iran being an Islamic republic since 1979), and flowers. It is also considered by many Iranians to be the city of gardens, due to the many gardens and fruit trees that can be seen in the city, for example Eram Garden. Shiraz has had major Jewish and Christian communities. The crafts of Shiraz consist of inlaid mosaic work of triangular design; silver-ware; pile carpet-weaving and weaving of kilim in the villages and among the tribes. In Shiraz industries such as cement production, sugar, fertilizers, textile products, wood products, metalwork and rugs dominate. Shirāz also has a major oil refinery and is also a major center for Iran’s electronic industries: 53% of Iran’s electronic investment has been centered in Shiraz. Shiraz is home to Iran’s first solar power plant. Recently the city’s first wind turbine has been installed above Babakuhi mountain near the city.

ZAND DYNASTY

Zand dynasty was an Iranian dynasty founded by Karim Khan Zand (1751-79) that initially ruled southern and central Iran in the 18th century. It later quickly came to expand to include much of the rest of contemporary Iran, as well as Azerbaijan, and parts of Iraq and Armenia.

The dynasty was founded by Karim Khan Zand, chief of the Zand tribe, who may have been originally Kurdish. Karim Khan declared Shiraz his capital, and in 1778 Tehran became the second capital. He gained control of central and southern parts of Iran. He refused to accept the title of the king and instead named himself Vakilol Ro’aya (Advocate of the People).

By 1760, Karim Khan had defeated all his rivals and controlled all of Iran except Khorasan, in the northeast. His foreign campaigns against Azerbaijan and the Ottomans brought Azerbaijan and the province of Basra into his control. But he never stopped his campaigns against his arch-enemy, the Qajars who he finally defeated.

Karim Khan’s monuments in Shiraz include the famous Arg of Karim Khan, Vakil Bazaar, and several mosques and gardens. He is also responsible for building of a palace in the town of Tehran, the future capital of the Qajar dynasty.

Decline and fall. Karim Khan’s death in 1779 left the territory vulnerable as his son and subsequent successors were incompetent. The biggest enemies of the Zands, the Qajars finally in 1794 captured and brutally killed the last king in the fortress of Bam, putting an effective end to the Zand Dynasty.

Politically, the Zands, especially Karim Khan, chose to call themselves Vakilol Ro’aya (Advocate of the People) instead of kings. Other than the obvious propaganda value of the title, it can be a reflection of the popular demands of the time, expecting rulers with popular leanings instead of absolute monarchs who were totally detached from the population, like the earlier Safavids.

Culture. The Zand era was an era of relative peace and economic growth for the country. Many territories that were once captured by the Ottomans in the late Safavid era were retaken, and Iran was once again a coherent and prosperous country. The art of this era is remarkable and, despite the short length of the dynasty, a distinct Zand art had the time to emerge. Many Qajar artistic traits were copied from the Zand examples.

In foreign policy, Karim Khan attempted to revive the Safavid era trade by allowing the British to establish a trading post in the port of Bushehr. This opened the hands of the British East India company in Iran and increased their influence in the country. The taxation system was reorganized in a way that taxes were levied fairly. The judicial system was fair and generally humane. Capital punishment was rarely implemented. Karim Khan Zand was a forward-thinking and popular leader, whom he credits as opening up international trade, employing a fair fiscal system and showing respect for co-existing religious institutions.

Nasir ol Molk Mosque. This traditional mosque was built during Qajar dynasty rule between 1876-1888. It is named the ‘Pink Mosque’ in popular culture due to the usage of considerable pink tiles for its interior design.

It has two sides. The entrance, courtyard and summer side have gorgeous floral tile work with stalactites, script and landscapes. The highlight of the summer side is the bright blue, green, yellow and red glass windows on the façade allowing sunlight to fill the mosque with colour.

It has two sides. The entrance, courtyard and summer side have gorgeous floral tile work with stalactites, script and landscapes. The highlight of the summer side is the bright blue, green, yellow and red glass windows on the façade allowing sunlight to fill the mosque with colour.

The winter side has more simple brick tiling and a mihrab so small I couldn’t find it.

This mosque is a museum and not actively used for religious purposes.

Naranjestan Museum. Part of Shiraz University, out front is a large courtyard garden with fountains, flowerbeds, palms and naranj trees (orange like fruit used to flavor kababs). The tile work shows many images of people and landscapes, unusual for Islam but the Qajars were quite westernized.

The museum complex starts with an open verandah covered in mirrors and Islamic design with elaborate inlaid wood doors. Just behind is the highlight Mirror Hall with intricate glass and mirror mosaics. One of the rooms upstairs has a ceiling of many round beams painted in intricate floral design with small scenes of humans, plants, animals and landscapes.

The museum shows products of the Shiraz Art School with artisans producing the works on site. The small marble boxes with intricate scenes were very nice. Many tiles were for sale but quite expensive.

Vakil Bazaar. A huge bazaar with one large L-shaped aisle with several side aisles, there was mainly cloth, carpets and household goods. A section surrounding a courtyard has more jewelry.

Vakil Mosque. Situated to the west of the Vakil Bazaar, it was built between 1751 and 1773, during the Zand period and restored in the 19th century during the Qajar period. Vakil means regent, the title used by Karim Khan, the founder of Zand Dynasty who endowed many buildings, including this mosque.

Vakil Mosque covers an area of 8,660 square meters. It has only two iwans instead of the usual four, on the northern and southern sides of a large open court. The iwans and court are decorated with typical Shirazi haft rangi tiles. Its night prayer hall contains 48 monolithic pillars carved in spirals, each with a capital of acanthus leaves. The minbar in this hall is cut from a solid piece of green marble with a flight of 14 steps and is considered to be one of the masterpieces of the Zand period. The exuberant floral decorative tiles largely date from the Qajar period.

The huge porticoed courtyard is covered with tiles and has a central pool and two large tiled entrances. The bottom of the wall is an intricate marble carved base. This side is not used for religious purposes and has a stone floor.

The winter side is small, much more austere and the one used for prayer.

Vakil Bath. This is a lovely bath house with a large octagonal pool, a massage room with a heated floor and a Jacuzzi. Wax figures surround the pool relating to the culture of the time.

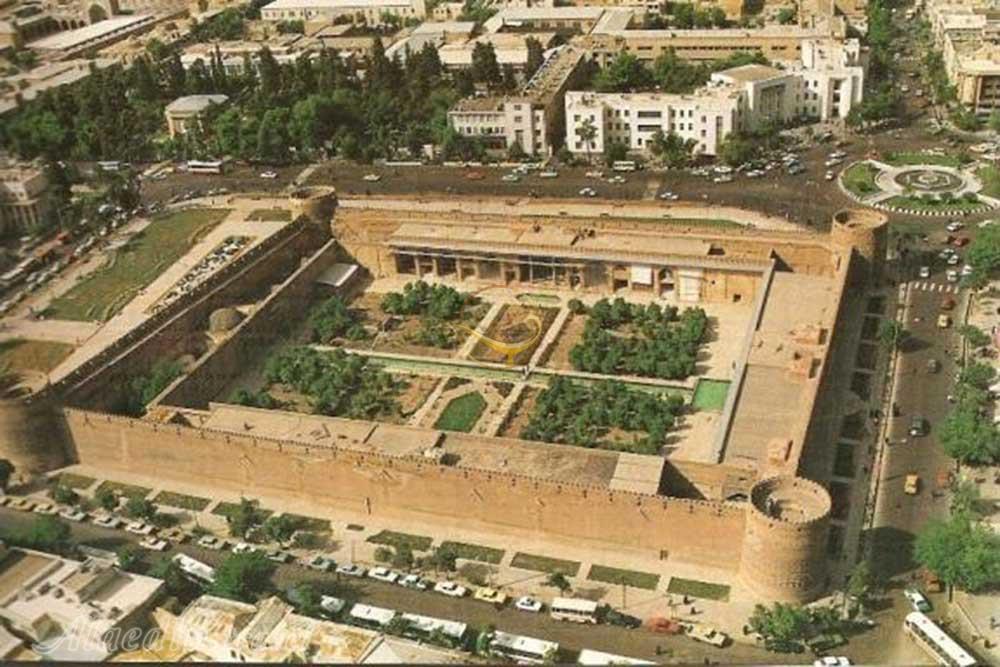

Arg of Karim Khan. This citadel is located in downtown Shiraz and was built in 1766-7 during the Zand dynasty as part of a complex. Rectangular in shape, resembles a medieval fortress combining military and residential architecture. It served as Karim Khan’s living quarters. The best architects and artists of the time and the best materials from other cities and abroad were used in the construction.

It has a land area of 4,000 m2 with four 12m-high walls, 3m thick at the base. Four 14m round brick towers decorated with brick designs are on each corner. One tower has subsided and leans at an angle. The highlight for me was the windows with stained glass in intricate wood designs. Tile works depicting legendary tales were added at the entrance gate of the citadel during the Qajar Era.

During the Qajar Period, it was used as the governor’s seat. After the fall of the Qajar Dynasty, it was converted into a prison and the paintings were plastered over. It was renovated starting in 1977 and is now a museum.

Ali-Ebn-e-Hamzeh Shrine. Ali bin Hamza is a sacred figure for Shiites, the nephew of Shah e Cheragh, the 8th imam (one of the 12 imams of Shia Islam, of whom 11 are buried in Iraq and only one in Iran). He was a revolutionary leader objecting to the corruption and tyranny of the rulers. He was prosecuted by the caliph and fled to Shiraz in 805, but after staying hidden for a while, he was finally found and killed. Later on around 950, the local ruler built him a shrine that was later developed further.

The present structure was built in the 19th century over the tomb, the latest of several earlier incarnations destroyed by earthquakes. Its two minarets and majestic tiled Shirazi exterior dome overlook the surrounding cemetery.

Inside you are served tea and cookies before entering the shrine.

His tomb sits in the middle encased in by a metal grill under a massive dome surrounded by four side domes. Above the first meter of marble, everything is a fantastic display of geometric mirror mosaics typical of Iranian Qajar shrines. Some are faint yellow and green but it all appears a dazzling silver. Impressive stalactites decorate the domes. The wood jali windows and doors are completely lost in the brilliance of the place. Looking closely there are green mirror designs, blue script and black 5-sided stars but they too are lost in mirror work. Of all the “mirror” rooms I have seen in Iran so far, this beats them all.

It is treated like a mosque – women wear chador, you take your shoes off and the floor is covered in Persian carpet. About half of the shrine (with the mihrab) is closed off to tourists by a 2m screen.

Ashura (the 10th day of the first month of the lunar Arabic calendar) celebrates his martyrdom. On the 40th day after Ashura, the Arba’Een March takes place in the holy city of Karbala, Iraq with about 20 million pilgrims, the world’s largest gathering

Shiraz Botanical Garden (Eram Garden). Both the building and the garden were built during the middle of the thirteenth century by the Ilkhanate or a paramount chief of the Qashqai tribes of Pars. The original layout of the garden however, with its quadripartite Persian Paradise garden structure was most likely laid in the eleventh century by the Seljuqs and was then referred to as Bāgh-e Shāh (“The emperor’s garden” in Persian) and was much less complicated or ornamental. Cornelius de Bruyn, a traveller from the Netherlands, wrote a description of the gardens in the eighteenth century.

Over its 150 years, the structure has been modified, restored or stylistically changed by various participants. It was one of the properties of the noble Shiraz Qavami Family. The building faces south along the long axis. The structure housed 32 rooms on two stories, decorated by tiles with poems from the poet Hafez written on them. The structure underwent renovation during the Zand and Qajar dynasties.

The compound came under the protection of Pahlavi University during the Pahlavi era and was used as the College of Law. The building also housed the Asia Institute.

Today, Eram Garden and its building are within the Shiraz Botanical Garden (established in 1983) of Shiraz University. They are open to the public as a historic landscape garden. They are a World Heritage Site and are protected by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization.

Day 5

We left Shiraz on our way to Yazd and saw Pasargadae on the way. It is about 110kms NE of Shiraz.

PASARGADAE (from Old Persian “protective club” or “strong club”).

This was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), who ordered its construction. It is located near the city of Shiraz. Today it is an archaeological site and one of Iran’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A limestone tomb there is believed to be that of Cyrus the Great.

History. Cyrus the Great began building the capital in 546 BC or later; it was unfinished when he died in battle, in 530 or 529 BC. The remains of the tomb of Cyrus’ son and successor Cambyses II were found in Pasargadae, near the fortress of Toll-e Takht, and identified in 2006.

Pasargadae remained the capital of the Achaemenid Empire until Cambyses II moved it to Susa; later, Darius founded another in Persepolis. The archaeological site covers 1.6km2 and includes a structure commonly believed to be the Mausoleum of Cyrus, the fortress of Toll-e Takht sitting on top of a nearby hill, the remains of a stone tower thought to be the tomb of Cambyses I (like the Zoratrian cube at Nasqsh-e Rostam), the Private Palace (doorway and bottoms of 14 of the 30 columns on a granite base still exist) and the Audience Hall (one intact 13m column, bases of 7 other columns and 3 of the eight corner towers). The Gate R, located at the eastern edge of the palace area, is the oldest known freestanding propylaeum. It may have been the architectural predecessor of the Gate of All Nations at Persepolis.

Pasargadae Persian Gardens provide the earliest known example of the Persian chahar bagh, or fourfold garden design but all that remains now are the foundations of a fountain area and the irrigation channels that run through much of the area.

Also here, but not related to the WHS, is the Mazoffaran Caravanserai, most ruins.

Tomb of Cyrus the Great “I am Cyrus the king, an Achaemenid” in Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian languages is carved in a column in Pasargadae.

The most important monument in Pasargadae is the tomb of Cyrus the Great. It has six broad steps leading to the sepulchre, the chamber of which measures 3.17m long by 2.11m wide by 2.11m high and has a low and narrow entrance. Though there is no firm evidence identifying the tomb as that of Cyrus, Greek historians say that Alexander believed it was. When Alexander looted and destroyed Persepolis, he paid a visit to the tomb of Cyrus. Arrian, writing in the second century AD, recorded that Alexander commanded Aristobulus, one of his warriors, to enter the monument. Inside he found a golden bed, a table set with drinking vessels, a gold coffin, some ornaments studded with precious stones and an inscription on the tomb. No trace of any such inscription survives, and there is considerable disagreement to the exact wording of the text. Strabo reports that it read: Passer-by, I am Cyrus, who gave the Persians an empire and was king of Asia.

Grudge me not therefore this monument.

Another variation, as documented in Persia: The Immortal Kingdom, is:

O man, whoever thou art, from wheresoever thou comest, for I know you shall come, I am Cyrus, who founded the empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not, therefore, this little earth that covers my body.

The design of Cyrus’ tomb is credited to Mesopotamian or Elamite ziggurats, but the cella is usually attributed to Urartu tombs of an earlier period. In particular, the tomb at Pasargadae has almost the same dimensions as the tomb of Alyattes, father of the Lydian King Croesus; however, some have refused the claim (according to Herodotus, Croesus was spared by Cyrus during the conquest of Lydia, and became a member of Cyrus’ court). The main decoration on the tomb is a rosette design over the door within the gable. In general, the art and architecture found at Pasargadae exemplified the Persian synthesis of various traditions, drawing on precedents from Elam, Babylon, Assyria, and ancient Egypt, with the addition of some Anatolian influences.

Archaeology. The first capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Pasargadae lies in ruins 40’40 kilometers from Persepolis, in present-day Fars province of Iran.

Pasargadae was first archaeologically explored by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld in 1905, and again in 1928. Since 1946, the original documents, notebooks, photographs, fragments of wall paintings and pottery from the early excavations are preserved in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC. After Herzfeld, Sir Aurel Stein completed a site plan for Pasargadae in 1934. In 1935, Erich F. Schmidt produced a series of aerial photographs of the entire complex.

It was during the 1960s that a pot hoard known as the Pasargadae Treasure was excavated near the foundations of ‘Pavilion B’ at the site. Dating to the 5th-4th centuries BC, the treasure consists of ornate Achaemenid jewelry made from gold and precious gems and is now housed in the National Museum of Iran and the British Museum. It has been suggested that the treasure was buried as a subsequent action once Alexander the Great approached with his army, then remained buried, hinting at violence.

The complex is one of the key cultural heritage sites for tourism in Iran.

Sivand Dam controversy.

There has been growing concern regarding the proposed Sivand Dam, named after the nearby town of Sivand. Despite planning that has stretched over 10 years, Iran’s own Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization was not aware of the broader areas of flooding during much of this time.

Its placement between both the ruins of Pasargadae and Persepolis has many archaeologists and Iranians worried that the dam will flood these UNESCO World Heritage sites, although scientists involved with the construction say this is not obvious because the sites sit above the planned waterline. Of the two sites, Pasargadae is the one considered to be more threatened. Experts agree that the planning of future dam projects in Iran will merit an earlier examination of the risks to cultural resource properties.

Of broadly shared concern to archaeologists is the effect of the increase in humidity caused by the lake. All agree that the humidity created by it will speed up the destruction of Pasargadae, yet experts from the Ministry of Energy believe it could be partially compensated for by controlling the water level of the reservoir.

Construction of the dam began 19 April 2007, with the height of the waterline limited so as to mitigate damage to the ruins.

In popular culture.

In 1930, the Brazilian poet Manuel Bandeira published a poem called “Vou-me embora pra Pasárgada” (“I’m off to Pasargadae” in Portuguese), in a book entitled Libertinagem. It tells the story of a man who wants to go to Pasargadae, described in the poem as a utopian city.

A festival celebrating Cyrus the Great was held previously every year. 2 years ago, 3 million attended. There were several demonstrations with chanting of “Down the Mullahs” and since the festival has been cancelled.