Iran – Esfahan, Chaharmahal/Bakhtiari, Kohgiluyeh/Boyer-Ahmad October 19-21, 2019

Day 8: Drive to Isfahan, visit Meybod, Nain & Varzaneh on the way

The road between Yazd/Mabod passes through some bleak desert – a flat plain between rugged mountains on either side.

NAIN

More than 3,000 years ago the Persians learned how to construct aqueducts underground (qanat in Persian kariz) to bring water from the mountains to the plains. In the 1960s this ancient system provided more than 70 percent of the water used in Iran. Nain is one of the best places in the world to see these qanats functioning.

Unique to Nain are some ancient monuments:

Narenj Castle. With a pre-Islamic origin, this very high mud brick edifice is a giant ruin, melting away with each rain. It looks like restoration has started but appears a little late.

Jame’ Mosque. One of the first four mosques built in Iran after the Arab invasion, it is in decrepit shape. This 1000-year-old mosque has some intricate designs on the columns and mihrab and a nice carved wood minbar, but the rest is crumbling. It is a museum and not actively used.

Cisterns. They are surrounded by wind towers used to direct air onto the water keeping it fresh.

Pirnia traditional house

Old Bazaar, Rigareh

Qanat-based watermill. Accidentally discovered during the construction of a road.

VARZANEH is Famous for its spectacular desert having the highest sand dunes. Unique to Varzaneh, are the local women’s costumes – typically white chadors, rather than black.

Attractions in Varzaneh include Gavkhouni Wetland and Black Mountain, Salt Lake. Jame Mosque of Varzaneh, Old Bridge, Ghoortan Citadel, Pigeon Towers, Camel-mill Complex, Ox-well Complex, Caravansary and Water reservoirs and Wind-towers.

Day 9: Visiting Isfahan

ISFAHAN (pop 2 million, metro 4 million)

It is 406 km south of Tehran at the intersection of the two principal north-south and east-west routes that traverse Iran. It is the third largest city in Iran after Tehran and Mashhad but was once one of the largest cities in the world.

Isfahan flourished from 1050 to 1722, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries under the Safavid dynasty when it became the capital of Persia for the second time in its history under Shah Abbas the Great. Even today the city retains much of its past glory.

It is famous for its Perso–Islamic architecture, grand boulevards, covered bridges, palaces, tiled mosques, and minarets. Isfahan also has many historical buildings, monuments, paintings and artifacts. The fame of Isfahan led to the Persian pun and proverb “Isfahan is half (of) the world”.

The legendary city which never fails to enchant its visitors, is the pearl of traditional Islamic archeology. This city is revived by the works of contemporary artists. Isfahan prides itself on having fascinating historical garden palaces. Legend has it that the city was founded at the time of Tahmoures or Keykavous and because of its glories has been entitled “Half the World”.

The Naghsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan is one of the largest city squares in the world. UNESCO has designated it a World Heritage Site.

HISTORY

Prehistory. Human habitation has occurred in the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages.

Zoroastrian era. It emerged in the Elamite civilization (2700–1600 BCE) benefiting from the exceptionally fertile soil on the banks of the Zayandehrud River. In the Achaemenid Empire (648–330 BCE), Cyrus the Great (reg. 559–529 BCE) showed his fabled religious tolerance. After Cyrus took Babylon in 538 BCE, he declared that the Jews in Babylon could return to Jerusalem. Some of these freed Jews settled in Isfahan. The Parthians (250–226 BCE) continued the tradition of tolerance.

The Sassanids (226–652 CE) instituted agricultural reform and revived Iranian culture and the Zoroastrian religion. Its strategic location at the intersection of the ancient roads to Susa and Persepolis required a standing army.

Islamic era. When the Arabs captured Isfahan in 642, they made it the capital of ancient Media and Isfahan grew prosperous. In the Turkish Seljuq dynasty, it was the capital and under Malik-Shah I (r. 1073–92), the city grew in size and splendour.

After the fall of the Seljuqs (c. 1200), Isfahan temporarily declined and was eclipsed by other Iranian cities such as Tabriz and Qazvin. In 1327, Ibn Battuta noted that it was in ruins for the greater part.

During the Safavid period (1501–1736), the city’s golden age began in 1598 when the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I (reigned 1588–1629) moved his capital from Qazvin to the more central Isfahan and rebuilt it into one of the largest and most beautiful cities in the 17th-century world – a golden age for the city, with architecture and Persian culture flourishing. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of deportees and migrants from the Caucasus emigrated en masse to the city. Now the city had enclaves in 1685, of 20,000 Georgians, Circassians, and Daghistanis. 300,000 Armenians from near the unstable Safavid-Ottoman border resettled here forming the Armenian Quarter of Isfahan, today called New Jolfa with Armenian churches and shops and still one of the oldest and largest Armenian quarters in the world. The Vank Cathedral is noted for its combination of Armenian Christian and Iranian Islamic elements. The royal court in Isfahan had a great number of Georgian ḡolāms (military slaves), as well as Georgian women. During Abbas’s reign, Isfahan became very famous in Europe with many European travellers. This prosperity lasted until it was sacked by Afghan invaders in 1722 during a marked decline in Safavid influence.

Thereafter, Isfahan experienced a decline in importance, culminating in a move of the capital to Mashhad and Shiraz during the Afsharid and Zand periods respectively, until it was finally moved to Tehran in 1775 by Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty. In the early years of the 19th century, efforts were made to preserve some of Ifsahan’s archeologically important buildings.

Modern age. In the 20th century, Isfahan was resettled by a very large number of people from southern Iran, firstly during the population migrations at the start of the century, and again in the 1980s following the Iran–Iraq War.

Today, Isfahan produces fine carpets, textiles, steel, handicrafts, and traditional foods including sweets. There are nuclear experimental reactors as well as facilities for producing nuclear fuel (UCF) within the environs of the city. Isfahan has large steel and metal alloy facilities. Mobarakeh Steel Company is the biggest steel producer in the whole of the Middle East and Northern Africa.

There is a major oil refinery and a large airforce base outside the city. HESA, Iran’s most advanced aircraft manufacturing plant, is located just outside the city.

GEOGRAPHY and CLIMATE

The city is located in the lush plain of the Zayanderud River in the eastern foothills of the Zagros mountain range. The river flows from the west through the heart of the city, then dissipates in the Gavkhooni wetland. The nearest mountain is Mount Soffeh, just south of the city. No geological obstacles exist 90 km north of Isfahan, allowing cool winds to blow from this direction. Situated at 1,590 metres (5,217 ft) above sea level, Isfahan has an arid climate. Despite its altitude, it is hot during the summer, with a maximum of around 35 °C. However, with low humidity and moderate temperatures at night, the climate is quite pleasant. During the winter, days are mild while nights can be cold. Snow has occurred at least once every winter except 1986/1987 and 1989/1990.

The city centre consists of an older section revolving around the Jameh Mosque, and the Safavid expansion around Naqsh-e Jahan Square, with nearby places of worship, palaces, and bazaars.

SIGHTS

Bazaars: Shahi Bazaar – 17th century, Qeysarie Bazaar – 17th century

Bridges: The bridges on the Zayanderud River comprise some of the finest architecture in Isfahan.

Shahrestan bridge. The city’s oldest bridge, its foundations are (3rd -7th century) and was repaired during the Seljuk period.

Khaju bridge. Upstream, it was built in 1650. It is 123 metres (404 feet) long with 24 arches and also serves as a sluice gate.

Choobi (Joui) bridge. Originally an aqueduct to supply the palace gardens on the north bank of the river.

Si-o-Seh Pol (Bridge of 33 arches). Built during the reign of Shah Abbas, this 295m bridge links Isfahan with the Armenian suburb of New Julfa.

Churches and cathedrals: Bedkhem Church – 1627, St. Georg Church – 17th century, St. Jakob Church – 1607, St. Mary Church – 17th century, Vank Cathedral – 1664

Emamzadehs, Emamzadeh Ahmad, Emamzadeh Esmaeil, Isfahan, Emamzadeh Haroun-e-Velayat – 16th century, Emamzadeh Jafar, Emamzadeh Shah Zeyd

Gardens and parks. Birds Garden, Flower Garden< Nazhvan Recreational Complex

Houses: Alam’s House, Amin’s House, Malek Vineyard, Qazvinis’ House – 19th century, Sheykh ol-Eslam’s House

Mausoleums and tombs: Al-Rashid Mausoleum – 12th century, Baba Ghassem Mausoleum – 14th century, Mausoleum of Safavid Princes, Nizam al-Mulk Tomb – 11th century, Saeb Mausoleum, Shahshahan mausoleum – 15th century, Soltan Bakht Agha Mausoleum – 14th century

Minarets: Ali minaret – 11th century, Bagh-e-Ghoushkhane minaret – 14th century, Chehel Dokhtaran minaret – 12 century, Dardasht minarets – 14th century, Darozziafe minarets – 14th century, Menar Jonban – 14th century, Sarban minaret

Mosques: Agha Nour mosque – 16th century, Hakim Mosque, Ilchi mosque, Jameh Mosque, Jarchi mosque – 1610, Lonban mosque, Maghsoudbeyk mosque – 1601, Mohammad Jafar Abadei mosque – 1878, Rahim Khan mosque – 19th century, Roknolmolk mosque, Seyyed mosque – 19th century, Shah Mosque – 1629, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque – 1618

Museums: Contemporary Arts Museum Isfahan, Isfahan City Centre Museum, Museum of Decorative Arts, Natural History Museum of Isfahan – 15th century

Schools (madresse): Chahar Bagh School – early 17th century, Harati, Kassegaran school – 1694, Madreseye Khajoo, Nimavar school – 1691, Sadr school – 19th century

Palaces and caravanserais: Ali Qapu (The Royal Palace) – early 17th century, Chehel Sotoun (The Palace of Forty Columns) – 1647, Hasht-Behesht (The Palace of Eight Paradises) – 1669, Shah Caravanserai, Talar Ashraf (The Palace of Ashraf) – 1650

Squares and streets: Chaharbagh Boulevard – 1596, Chaharbagh-e-khajou Boulevard, Meydan Kohne (Old Square), Naqsh-e Jahan Square also known as “Shah Square” or “Imam Square” – 1602,

Synagogues: Kenisa-ye Bozorg (Mirakhor’s kenisa), Kenisa-ye Molla Rabbi, Kenisa-ye Sang-bast, Mullah Jacob Synagogue, Mullah Neissan Synagogue, Kenisa-ye Keter David

Tourist attractions: The central historical area in Isfahan is called Seeosepol (the name of a famous bridge).

Other sites: Atashgah – a Zoroastrian fire temple, The Bathhouse of Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī, Isfahan City Centre, Jarchi hammam, New Julfa – 1606, Pigeon Towers – 17th century, Takht-e Foulad

In Isfahan, we stayed at the Keryas Hotel, a large 200-year-old Persian House from the Qajar era with a central courtyard. My room was gorgeous with 20-foot ceilings, a king-sized bed and a TV with a few English channels including BBC. The house was almost a complete ruin with a total renovation finished just one year ago. It sits directly behind the Shah Mosque and is about one block walk from the Maiden (large square).

Khaju Bridge. Built in 1650, it is 123 metres (404 feet) long with 24 arches, and also serves as a sluice gate.

This is a very unusual large bridge with two decks, both with arcades. The upper deck was used by cars until about 2004. This road surface is 8m wide with arcades on another 2.5m on either side of the deck. The lower deck has always been pedestrian and extends about 3m on the west and 7m on the east out from the upper deck. There are steps on the wide east side where people congregate.

On both sides in the center is a small 2-story pavilion where the king used to come to watch the water splashing festival in June. The water channels could be closed to form a reservoir on the upstream west side. There is a dam 360 km upstream that controls water levels – floods were common where water came over the upper deck.

Shahrestan bridge. The oldest bridge on the Zayandeh River in Iran. The foundations date back to the Sasanian era (3rd to 7th century C.E.), but the top was renovated twice, first in the 10th century by the Buyids, then during the 11th century during the Seljuk period. Nevertheless, the architectural style is entirely Sassanian.

The bridge consists of two parabolas. The vertical parabola ensures that the middle of the bridge is its highest point. The horizontal parabola produces a bend to the west, strengthening it against the flow of the river. The bridge is 107.8 metres long and an average of 5.2 metres wide. It has two tiers of pointed arches, thirteen large ones spanning the river itself, and eight smaller ones that nest between them. The purpose of the latter is to quicken the flow of water during floods, taking pressure off the structure. The Zayandeh River has recently been diverted about 100 meters away from the bridge towards the south, leaving an artificial lake around the bridge to protect it from further damage.

Chehel Sutoon Garden and Palace. Built by Shah Abbas, this palace should not be missed. Walk beside the large rectangular pool to the open porch supported by 20 cedar columns, four with bases of 4 lions. It opens into the Mirror Hall entrance before entering the main hall. The walls are covered in large paintings showing battles, meetings and the life of the court. The windows have lovely wood Islamic orosi wood designs.

MEIDAN EMAM (Naghsh-e Jahan Square, Shah Square, Imam Square), is a square in the center of Isfahan. Constructed between 1598 and 1629, it is now an important historical site and one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites. It is 160m wide by 560m long (an area of 89,600 square metres (964,000 sq ft)). The square is surrounded by buildings from the Safavid era – the Shah Mosque on the south, the Ali Qapu Palace on the west, the Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque on the east, and at the northern side, the Qeysarie Gate opens into the Isfahan Grand Bazaar. Today, the Muslim Friday prayer is held in the Shah Mosque. The square is depicted on the reverse of the Iranian 20,000 rials banknote.

It is the largest enclosed square in the world and second only to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in size.

History. In 1598, Shah Abbas moved the capital of his empire from the north-western city of Qazvin to the central city of Isfahan and initiated the greatest building program in Persian history, completely remaking the city. Isfahan sat on the Zāyande roud (“The life-giving river”), an oasis of intense cultivation amid a vast area of arid landscape. Isfahan distanced his capital from any future assaults by the Ottomans, the arch-rival of the Safavids, and the Uzbeks, and at the same time gained more control over the Persian Gulf, which had recently become an important trading route for the Dutch and British East India Companies.

The two key features of Shah Abbas’s master plan were Chahar Bagh Avenue, flanked at either side by all the prominent institutions of the city, such as the residences of all foreign dignitaries, and the Naqsh-e Jahan Square. Before the Shah’s ascent to power, Persia was decentralized with the military and governors battling for power. The square, or Maidān gathered together the three main components of power in Persia: the clergy, (Masjed-e Shah), the merchants (Imperial Bazaar), and the power of the Shah (residing in the Ali Qapu Palace).

The Maidan was where the Shah and the people met. Built as a two-story row of 200 shops, flanked by the palace and two mosques, it led up to the northern end, where the Imperial Bazaar was. The square was a busy arena of entertainment and business, exchanged between people from all corners of the world. As Isfahan was a vital stop along the Silk Road, goods from all the civilized countries of the world, spanning from Portugal in the West to the Middle Kingdom in the East, found their way to the hands of gifted merchants, who knew how to make the best profits out of them.

During the day, the square was occupied by the tents and stalls of tradesmen, entertainers and actors. For the hungry, cooked foods, melon, and water were readily available. At dusk, the shopkeepers packed up and were replaced by dervishes, mummers, jugglers, puppet-players, acrobats and prostitutes.

The square could be cleared for public ceremonies and festivities – Nowruz, the Persian New Year and the national Persian sport of polo. The marble goalposts, erected by Shah Abbas, are in the National Museum but stone posts still stand at either end of the Maydan.

Under Abbas, Isfahan became a very cosmopolitan city, with a resident population of Turks, Georgians, Armenians, Indians, Chinese and a growing number of Europeans. Shah Abbas brought in some 300 Chinese artisans to work in the royal workshops and to teach the art of porcelain-making. The Indians were present in very large numbers, housed in the many caravanserais that were dedicated to them, and they mainly worked as merchants and money changers. The Europeans were there as merchants, Roman Catholic missionaries, artists and craftsmen. Even soldiers, usually with expertise in artillery, would make the journey from Europe to Persia to make a living. The Portuguese ambassador, De Gouvea, once stated: “The people of Isfahan are very open in their dealings with foreigners, having to deal every day with people of several other nations.”

The maidān has a peculiar orientation and doesn’t lie in alignment with Mecca, so that when entering the entrance portal of both the Shah and Lotfollah Mosque, one makes, almost without realizing it, the half-right turn that enables the main court within to face Mecca. The most plausible explanation is; that the vision was for the domes of the mosque to be visible wherever in the maydān a person was situated. Had the axis of the maydān coincided with the axis of Mecca, the dome of the mosque would have been concealed from view by the towering entrance portal leading to it. By creating an angle between them, the two parts of the building, the entrance portal and the dome, are in perfect view for everyone within the square to admire.

Today the square is a popular place for Iranians with a large pool with 25 geyser fountains, lawns, bushes, star-shaped flower beds and plazas. Many Iranian families were picnicking on the grass with their propane burners.

Masjed-e Shah (Shah Mosque, Imam Khomeini Mosque). The crown jewel of the square, this mosque replaced the Jameh Mosque for conducting the Friday prayers. To achieve this, the Shah Mosque was constructed not only with a vision of grandeur, having the largest dome in the city, but also having a religious school and a winter mosque clamped at either side of it.

The grand portal has several vaulted open domes with muqarnas and 4 minarets. The silver door had several bullet holes from Afghan bullets in 1722. The corridor makes a 45° turn to enter a huge courtyard lined by two stories of alcoves covered in blue tiles. The other two sides also have large arched portals each with alabaster basins for juice. The main chamber has a double dome that echoes sound. The majestic mihrab has a rectangular basin where the mullahs stood in prayer and then ascended the solid 14-step stairs to the minbar where they could preach to the masses from above. This is only a tourist attraction now and the winter mosque in the SE corner serves as the active “mosque”.

A mullah sits in the courtyard ready to talk to tourists about Islam and Iran. We talked for at least 30 minutes asking as probing questions as we could. The guy was a skilled politician easily evading how Islam deals with apostates, atheists, Sunni Islam, Saudi Arabia and the common situation where young Iranians often don’t get married and live together.

The Lotfollah Mosque (Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Women’s Mosque). The first structure was built on the square in 1028, it was a private mosque of the royal court. For this reason, the mosque does not have any minarets and is smaller. A tunnel goes under the square from the Ali Qapu Palace so that the royal women can go to the mosque unnoticed. Like the Shah Mosque, the entrance turns 45º so the mosque faces Mecca.

Centuries later, it was opened to the public to admire the effort that Shah Abbas had put into making this a sacred place for the ladies of his harem, and the exquisite tile work, which is far superior to those covering the Shah Mosque – the tile colours are yellow (saffron), blue (lapis lazuli), green (pistachio) and tan (walnut). Turquoise spiral columns frame large arches of tile with Koran script and floral patterns. The signature mihrab dates from 1028 and has dates and the signature of the Lebanese designer.

Ali Qapu Palace. Ali Qapu is a pavilion that marks the entrance to the vast royal residential quarter of the Safavid Isfahan which stretched from the Maidan Naqsh-e Jahan to the Chahar Bagh Boulevard. The name is made of two elements: “Ali”, Arabic for exalted, and “Qapu” Turkic for portal or royal threshold – “Exalted Porte”. It was here that the great monarch used to entertain noble visitors and foreign ambassadors. Shah Abbas, here for the first time celebrated the Nowruz (New Year’s Day) in 1597 A.D. A large and massive rectangular structure, the Ali Qapu is 48m high and has six floors, fronted with a wide terrace on the third floor facing the square whose ceiling is inlaid and supported by 18 wooden columns. A 4x5m pool is lined with 79 copper sheets.

On the 6th floor is the Music Room where royal receptions, the largest rooms and banquets were held. The stucco decoration of the banquet hall abounds with motifs of various cutout vessels and cups. Various ensembles performed music and sang songs with the sound amplified for up to one kilometre away. From the upper galleries, the Safavid ruler watched polo games, maneuvers and horse racing below in the Naqsh-e Jahan Square.

The Imperial Bazaar. This historical market is one of the oldest and largest bazaars in the Middle East. Although the present structure dates back to the Safavid era, parts of it are more than a thousand years old from the Seljuq dynasty. It is a vaulted, two-kilometer street linking the old city with the new. Inside it is a maze of shops showing the huge variety of Isfahan crafts – guys banging on copper pots, silversmiths using punches on silver plates placed on a block of tar, ceramics, jewelry and clothes everywhere. The bizarre continues on both sides of the square behind the arcades.

At the entrance to the Imperial Bazaar, there were coffee houses, where people could relax over a cup of fresh coffee and a water pipe. These shops can still be found today, although the drink in fashion for the past century has been tea, rather than coffee.

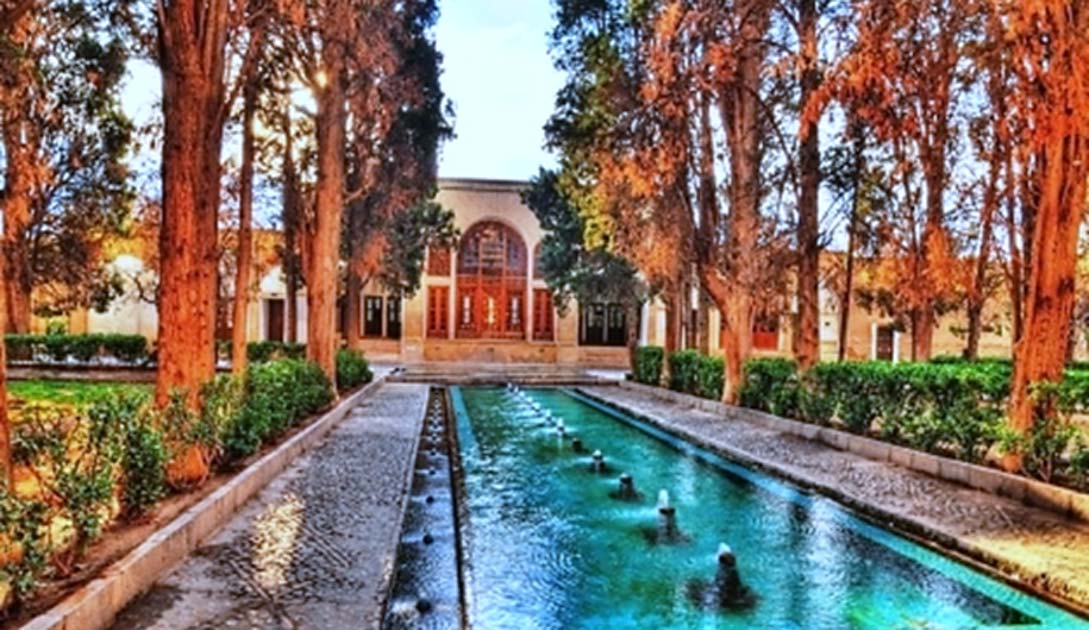

Hasht Bchasht Palace (Eight Mistress Palace). On the other side of Chahar Bagh Avenue and the residence of the shah, this was a two-story apartment building for the eight mistresses of the shah. Each apartment was lavishly decorated with muqarnas and fireplaces. The gardens are lovely with a long rectangular pool in front, grass and mature trees.

Day 10: Visiting Isfahan

Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan (Jāmeh Mosque) is the grand, congregational mosque in Isfahan. The mosque is the result of continual construction, reconstruction, additions and renovations on the site from around 771 to the end of the 20th century. The Grand Bazaar of Isfahan can be found towards the southwest wing of the mosque. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2012.

Built during the Umayyad dynasty, it is rumoured that one of the pillars of this Mosque was personally built by the Caliph in Damascus. Before it became a Mosque, it is said to have been a house of worship for Zoroastrians. This is one of the oldest mosques still standing in Iran, and it was built in the four-iwan architectural style, placing four gates face to face. An iwan is a vaulted open room. The qibla iwan on the southern side of the mosque was vaulted with muqarnas during the 13th century. Muqarnas are niche-like cells.

Construction under the Seljuqs included the addition of two brick-domed chambers, for which the mosque is renowned. The south dome was built to house the mihrab in 1086–87 and was larger than any dome known at its time. The north dome was constructed a year later. Further additions and modifications took place incorporating elements from the Mongols, Muzzafarids, Timurids and Safavid with different architectural styles, so now the mosque represents a condensed history of Iranian Architecture.

Allahverdi Khan Bridge (Si-o-seh pol Bridge). The bridge of thirty-three spans. It is one of the most famous examples of Safavid bridge design and the longest bridge on the Zayanderud (the largest river of the Iranian Plateau in central Iran) with a total length of 297.76 meters. At 15m wide, it was once a car bridge but now is only pedestrian. A row of arcaded brick structures lines both sides of the top, but there are no buildings. Underneath, a stone step in each span allows you to walk the length of the bridge, a nice cool spot in the heat of the day.

We walked over the bridge to New Julfa, the Armenian section of Isfahan. Before lunch, we went to a carpet store with 5,500 carpets and they proceeded to show us most of them. Carpets are of two types: Nomad and City with significant distinctions. Prices ranged from $250 to $25,000 (3x4m and all silk with 170 knots per centimetre). Two of the group finally bought a carpet.

Vank Cathedral. One of the most beautiful Armenian churches in the world, it shows elements of Armenian, Islamic and European architecture. The small church is completely painted on the inside and supplies a nice guide to all the Old and New Testament Bible stories on the walls. There is also a museum with many religious artifacts (many Bibles) and ethnography.

Abbasi Hotel. In a previous caravanserai, this is Isfahan’s most expensive hotel with 2-stories of arcaded rooms with balconies, many designed in the original Qajar style. The huge courtyard has a lovely garden with cushions on all the chairs – palm, quince, persimmon trees, ornamental flower beds, and sculpted bushes.

Menar Jonban. The tomb of a Sufi with its shaking minarets and some historical bridges.

Day 11: Drive to Kashan, visit Natanz & Abyaneh

NATANZ (12,100 2006)

Natanz is 70 km SE of Kashan. Its bracing climate and locally produced fruit, especially pear are well known in Iran. The Kansas mountain chain (Kuh-e Karkas) (meaning mountain of vultures), at an elevation of 3,899 meters, rises above the town.

Japanese companies bought all the pomegranate orchards in Natanz and shipped them all to Japan where they sell for $10 each.

Shrine of Abd as-Samad, The tomb honours the Sufi Sheikh Abd al-Samad, a famous Ilkhanid era Shi’ite Sufi of the 13th century. The shrine has 4 iwans, the oldest 1000 years old with a great dome. The Mongol additions dating from 1304 are the best Mongol monuments remaining in Iran. The original Mongol 37m minaret and pyramid-shaped dome are outstanding and in like-new condition. The façade has great tile and maqarnas work. The original mihrab and other interior portions also had wonderful tiles – all stolen and now in British, American and French museums. The congregational (Jameh) mosque of Natanz was built around the tomb. A functioning qanat flows through the middle and a 1,000-year-old tree sits outside. The ruins of a 1,200-year-old Zorastrian temple are about 100m east.

Nuclear facility. Natanz nuclear facility, located some 30 km NNW from the town (33°43′N 51°43′E) near a major highway, is generally recognized as Iran’s central facility for uranium enrichment with over 19,000 gas centrifuges currently operational and nearly half of them being fed with uranium hexafluoride.

Enrichment of uranium at the plant was halted in July 2004 during negotiations with European countries. In 2006, it resumed enrichment. In September 2007, 3,000 centrifuges were installed and enrichment programs restarted in March 2011. In 2013, five percent uranium enrichment continued at Natanz and 20 percent enrichment at Fordo and Natanz.

Between 2007–2010 Natanz nuclear power plant was hit by a sophisticated cyber attack that was carried out by German, American, Dutch and Israeli intelligence organizations. The attack used a Stuxnet worm which hampered the operation of the plant’s centrifuges and caused damage to them over time. The goal of the cyber attack was not to destroy the nuclear program of Iran completely but to stall it enough for sanctions and diplomacy to take effect. This was successful as a nuclear treaty with Iran was reached in July 2015 but the US cancelled its portion of the agreement in 2017 and enrichment again resumed.

Castle of Tarq. This historic castle from the Sassanid era is located in the Tarq Rud village. It is slowly crumbling with the mud-brick melting away with each rain. There is little here. We entered the fort. Some buildings have been replastered but saving the fort looks hopeless. The highlight may be the large hand holding a pomegranate in the small roundabout.

ABYANEDH

The Historical Village of Abyaneh is a tentative WHS (09/08/2007) located in the desert at the foot of Mount Karkas (Vulture Mountain 3,900m and usually snow-capped in the winter). This serene, quaint village has some archaeology – on top of the village sits the ruins of a Sassanid-era fort. The dwellers speak, live and dress in the original Persian style. The dialect has preserved some characteristics of the Middle Persian language, the language of the Sassanian Persia. Our guides could not understand it. Women dress as they did 1000 years ago – Abyanaki women typically wear a white long scarf (covering the shoulders and upper trunk) that has a colourful pattern and an under-knee skirt. Abyunaki people have persistently maintained this traditional costume.

Characterized by a peculiar reddish hue, the village is one of the oldest in Iran, attracting numerous native and foreign tourists year-round, especially during traditional feasts and ceremonies. Most of the young people have left and now it is mostly elderly.

We walked through the lanes, ate flatbread baked by plastering the dough against the walls of the oven and visited the shrine of an imam. In the courtyard were two ancient grape vines with trunks 1 foot across. They spread out over an arbour above the central pool.

Martyrs of the Iran/Iraq War (1980-88). 180 – 220,000 Iranians died in this war, along with at least 12,000 civilians. Individual pictures of soldiers are everywhere in Iran especially lining highways. Towns have photos of their residents killed in the war on house fronts and power poles. A small memorial/shine to 19 martyrs was in the shrine to the imam in Abyanedh and a fighter jet memorial on the highway near the town was a memorial to an Iranian pilot.

No land or reparations changed hands during the war. It cost over a trillion dollars total.

KASHAN (pop 400,000)

In the northern part of Isfahan province, the Kasian were the original inhabitants of the city, whose remains are found at Tapeh Sialk dating back 9,000 years. Between the 12th and the 14th centuries, Kashan was an important centre for the production of high-quality pottery and tiles. In modern Persian, the word for a tile (Kashi) comes from the name of the town.

Kashan is divided into two parts, mountainous and desert. The west side is near two of the highest peaks of the Karkas chain, Mount Gargash to the southwest (the home of Iran National Observatory, the largest astronomical telescope of Iran) and to the west, Mount Ardehaal, the highest peak of Ardehaal mountains and end part of Karkas chain in central Iran.

The east side of Kashan opens up to the central Maranjab Desert of Iran with caravanserai located near a salt lake. The Shifting Sands is a popular destination at the weekends for safaris.

Historical Axis of Fin, Sialk, Kashan is a tentative WHS (09/08/2007). The exact definition of what locations within Kashan proper might be nominated was not made clear. In 2012 Iran successfully nominated the Fin Garden separately as a part of its Persian Gardens World Heritage Site.

History. The earliest evidence of human presence around Kashan dates back to the Paleolithic period. Kashan itself dates to the Elamite period of Iran – the Sialk ziggurat still stands today in the suburbs of Kashan after 7,000 years.

The artifacts uncovered at Sialk Mahan Pasha reside in the Louvre in Paris, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Iran’s National Museum.

By some accounts, Kashan was the origin of the three wise men who followed the star that guided them to Bethlehem to witness the nativity of Jesus, as recounted in the Bible. Whatever the historical validity of this story, the attribution of Kashan as their original home testifies to the city’s prestige at the time the story was set down.

Abu-Lu’lu’ah/Pirouz Nahāvandi, the Persian soldier who was enslaved by the Islamic conquerors and eventually assassinated the caliph Umar al-Khattab in AH 23 (643/4 CE), reportedly fled to Kashan after the assassination. His tomb is one of Kashan’s conspicuous landmarks.

Sultan Malik Shah I of the Seljuk dynasty ordered the building of a fortress in the middle of Kashan in the 11th century. The fortress walls, called Ghal’eh Jalali still stand today in central Kashan.

Kashan was also a leisure vacation spot for Safavi Kings. Bagh-e Fin (Fin Garden), specifically, is one of the most famous gardens of Iran. This beautiful garden with its pool and orchards was designed for Shah Abbas I as a classical Persian vision of paradise. The original Safavid buildings have been substantially replaced and rebuilt by the Qajar dynasty although the layout of trees and marble basins is close to the original. The garden itself, however, was first founded 7000 years ago alongside the Cheshmeh-ye-Soleiman. The garden is also notorious as the site of the murder of Mirza Taghi Khan known as Amir Kabir, chancellor of Nasser-al-Din Shah, Iran’s king in 1852.

The earthquake of 1778 levelled the city of Kashan and all the edifices of Shah Abbas Safavi, leaving 8000 casualties. But the city started afresh and has today become a focal tourist attraction via the numerous large houses from the 18th and 19th centuries, illustrating the finest examples of Qajari aesthetics.

Sights

Bagh-e Fin (Fin Garden, Fin Bathroom)

Architecture: Aminoddole carvansarai. Dokhtaran Fortress, Jalali Castle, Menar tower

Houses: Abbāsi House, Attarha House, Al-e Yaseen House, Āmeri House, Boroujerdi House, Manouchehris House, Tabātabāei House (1800s, A fine example of traditional Persian architecture)

Mosques: Agha Bozorg Mosque, Jameh Mosque of Kashan, Meydan Mosque, Tabriziha Mosque

Bathhouses: Sultan Amir Ahmad Bathhouse

Archaeology: Tepe Sialk, Ghal’eh jalali Fortress

Others: Bazaar of Kashan, Piruz Nahavandi Shrine (the assassin of Islam ‘s second Caliph), Timcheh Amin-o-dowleh

Today. Although there are many sites in Kashan of potential interest to tourists, the city remains largely undeveloped in this sector, with fewer than a thousand foreign tourists per year. Notable towns around Kashan are Qamsar and Abyaneh, which attract tourists all year around.

Kashan is internationally famous for manufacturing carpets, silk and other textiles. Today, Kashan houses most of Iran’s mechanized carpet-weaving factories, and has an active marble and copper mining industry.

Tabatabaeiha Historic House of the previous century’s architecture, the Qajar era. The architect said that he would build this huge house if he could marry the merchant’s daughter. He built a masterpiece with the highlight of the elaborate stucco decoration covering the walls of the courtyard and two pools. There were separate areas for each wife, one the 50-door room surrounded by more courtyards and elaborate coloured glass windows. Even the stables were extensive. The main hall had nicely painted walls and domes and lovely intricate stained glass windows.

House of Kaj, Manuchehr Sheybani Museum of Art.

We stayed overnight in Kashan at the Yasmin Hotel, a Qajar house with 15 rooms surrounding a large courtyard. There was no TV. In the evening, we walked over to the bazaar through a maze of narrow lanes, a place impossible to navigate without a mapping app.

Bazaar of Kashan. More atmospheric than most other bazaars, it is a maze of interconnected covered lanes. We happened upon a huge dome lavishly decorated with tiles. I asked a shopkeeper about it – it was a caravanserai in the old days where merchants in carpets would come to trade and stay. The two levels of arcades today hold several carpet stores and antique shops.

Day 12 Kashan, Qom, Tehran

Agha Bozorg Mosque. The entrance iwan is large with 2 wind towers. The courtyard has a large sunken garden with a pool. The simple mosque has a large plain brick with two minarets and a dome with little decoration inside, some Koranic script and simple floral paintings. Unusually the mihrab is in the corner and decorated with nice maqarnas and tiles. A sunken courtyard in the back has a volleyball net.

Underground City of Nooshabad. The largest underground city in the world, this multi-level series of tunnels (most 1.8m high and quite narrow) was used as a hiding place from robbers and invading peoples. The one-kilometer of tunnels had multiple rooms, narrow vertical connections between the stories (so that invaders could not access the other story), a qanat water supply, a large cistern, ventilation shafts and few entrances.

It dates from before the beginning of Islam 1,500 years ago and was used up to the Qajar period. 300,000

FIN GARDEN. Listed as a WHS in 2012, this historical Persian garden contains Kashan’s Fin Bath, where Amir Kabir, the Qajarid chancellor, was murdered by an assassin sent by King Nasereddin Shah in 1852 (Amir Kabir was eventually buried in Karbala Iraq). Completed in 1590, the Fin Garden is the oldest extant garden in Iran.

History. The garden in its present form was built under the reign of Abbas I of Persia (1571-1629), as a traditional bagh near the village of Fin, located a few kilometres southwest of Kashan. The garden was developed further during the Safavid dynasty, until Abbas II of Persia (1633-1666). It was highly recognized during the reign of Fat′h Ali Shah Qajar and was considerably expanded.

The garden subsequently suffered from neglect and was damaged several times until, in 1935, it was listed as a national property of Iran. It was put on the Tentative WHS List (8/09/2007) and declared a World Heritage Site on July 18, 2012.

Structure. The garden covers 2.3 hectares with a main yard surrounded by ramparts with four circular towers. The garden contains numerous 500-year-old cypress trees and combines architectural features of The Safavid, Zandiyeh and Qajar.

The Shotor Galou is a lavishly painted domed structure in the SW corner with another input into a deep infinity pool with fish. The paintings are blue/white drawings of animals, buildings and landscapes.

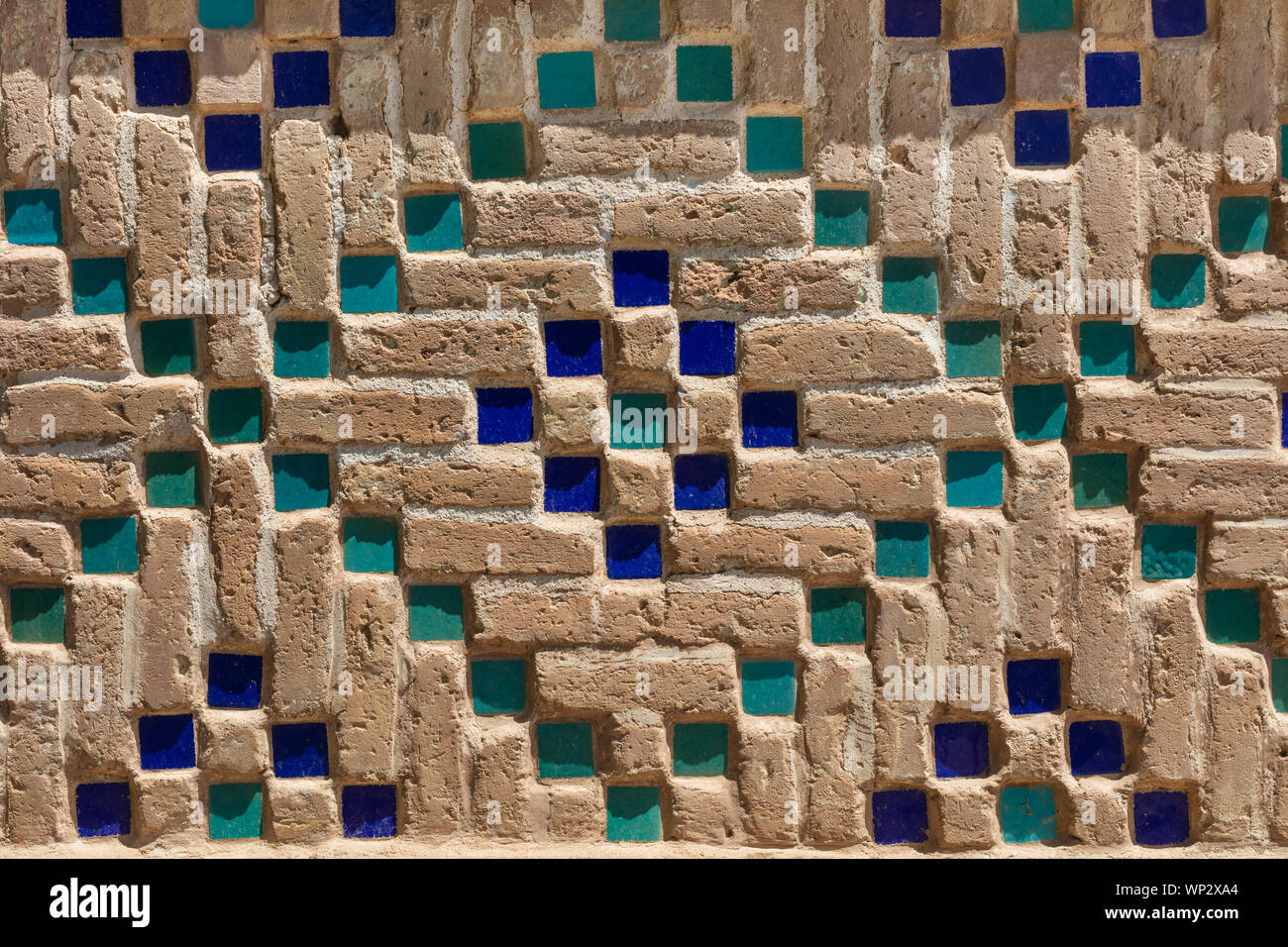

Water features. In keeping with many of the Persian gardens of this era, the Fin Garden employs a great many water features fed from a spring on a hillside behind the garden, and the water pressure was such that a large number of circulating pools and fountains could be constructed without the need for mechanical pumps. The main water input is a basin on the south side with 160 orifices, half water inputs and half water outputs. Water from here is directed to the 12-jet water basin, a long rectangular infinity pool. It next goes into canals that surround the circumference of the garden and into an infinity pool in the center of the small palace (where Shah Abbas kept his mistress) and then is directed out in three canals. All the interconnected pools and canals are lined with turquoise blue tiles and have water spouts running down the middle.

Don’t miss this one.