Syria – Southeast (Damascus, Daraa, as-Suwayda) November 1-3, 2019

I flew from Ashgabat to Istanbul on my way to Beirut, Lebanon and Syria. Despite having crossed into Turkey from Bulgaria on October 9, I had to get a visa (€50 even though I was simply transiting but had to self-transfer my luggage) as I was defrauded on the Bulgaria/Turkey land border by immigration. They took my €50 but didn’t give me a Turkey visa stamp. The border police, the man I paid the €50 to and the Turkish woman had a scheme to pocket my cash (they would have had to account for the stamp if they gave me one). This seems hard to believe but it happened. Even though I had crossed into Turkey before, I realized what had happened only long after. When I left Turkey to go to Iran, the immigration officer couldn’t understand how I had gotten into Turkey with no stamp. I spent at least an hour talking to visa violations, customs officers and police about what happened when I was in Istanbul Airport but to no avail.

I had a 5½ hour layover in Istanbul. After Iran and Turkmenistan, it felt good to be a relatively “normal” airport with a wide choice of food and stores. The new Istanbul airport is a monster with long walks.

Day 1

Beirut. I was picked up at the Beirut airport by a Lebanese as Syrians can’t drive to the airport, taken to a restaurant and waited 10 minutes for my Syrian driver to pick me up. Beirut – bombed-out buildings, a general level of decrepitude not seen for a while, wall-to-wall traffic, frequent military chokepoints with camo-painted barriers, sandbags, tiny guardhouses and soldiers wielding large guns. This was a huge change from Ashgabat which is ultra-clean and modern.

It seemed to take hours to get out of Beirut – the traffic was bad but the driver also didn’t seem to know where he was going and was constantly asking other drivers out the car window directions. It was nauseating dealing with all the heavy exhaust from trucks. I had no Lebanese or Syrian money (just $US) and no water. We finally stopped at a store – they accepted $US.

Visa. Mithra Tours, my tour operator had to do a lot of costly work to get the visa. I sent them my name and a scan of my passport and they filled out an application that is distributed to the many types of police in Syria – immigration, regular police, secret service police – who check your background, work history, and criminal records. Their recommendation is sent to the tourist ministry that, if approved, issues a permit for a visa. That permit is then sent to the immigration office at the border.

When you arrive at the Syrian immigration, go to the bank wicket in the large room, pay the $US 90 and get a receipt that is presented with your passport to one of the several immigration officers. They type in the information and put two stamps in your passport and you have your visa. The only question was what I did for work (retired was not good enough and I told him my past job). It ends up being quite simple and quick.

Neither me nor my driver understood any of this and it took a few phone calls to the tourist agency to know what to do. My driver didn’t know my name, that I was coming to Syria as a tourist, the hotel in Damascus and didn’t have a visa but was sent the permit letter. Thank god he spoke reasonable English.

Beit al Mamlouka Hotel. The hotel I stayed in the old part of Damascus was a 17th-century architectural masterpiece, a 5-star boutique hotel, the first in Damascus. Tucked away in a side street behind an inconspicuous door, you enter a wonderful courtyard with a fountain and trees. My room was the Baibar room named after the sultan who finally subdued Crac de Chevaliers. With 20-foot ceilings, original tile and ornate painted ceiling and furniture, a wood-beamed ceiling in the bathroom and a king-sized bed, I wondered how much I paid for it but it was only $80/night.

Old City of Damascus. This is an all-cobble narrow street ending in narrow alleys. The atmosphere is buildings in various states of decay and the crowds of pedestrians are made busier by all the parked cars and traffic allowed full access. At night cafes booming music are open very late, businesses still function at 1 am and a small section has many bars. Unlike most Muslim countries alcohol is common and many non-Sunni women wear nothing on their heads (Druize, Shia, Christians). Smoking is allowed everywhere.

I ate at a shwarma place owned and staffed by a family for over 30 years. Cheap and delicious, Syrian shwarma is different with only spiced meat cooked in a chicken broth, no vegetables, a tortilla crispy from the griddle and all squashed down like a panini. The owner loved to talk and I saw hundreds of pictures of his family and a place near the Turkey border in NW Syria.

That night I played cards with a bunch of 20-somethings, some who staff the hotel. I taught them Yavin, my favourite Israeli-originated card game.

Day 2 Bosra

Breakfast was an over-the-top spread, most wasted and not exactly what I would prefer.

My guide Mukhles picked me up at 9 am, we sat and enjoyed a coffee and smoke, then left for the 160km drive south of Damascus to Bosra. We passed through multiple military checkpoints – the left lane for taxis, buses and tour operators and the right for others, often much more crowded. Posters of Assad (and often his father) festoon the points. The checkpoints are primitive cinder blocks/barrels full of sand and small concrete guard houses.

We passed through the dry rocky country now brown and dry as all the crops have been harvested (mostly winter wheat). Some of the land is irrigated by artesian wells.

Gas in Damascus is 450/lire and after we crossed into Daraa District 225/litre, but many stations had run out of their weekly quota of gas.

Pass two types of “tent camps” – nomadic Bedouins with goats and sheep and Roma who exist on handicrafts and thievery. We also drove by villages once occupied by ISIS, full of destroyed buildings. In the war, snipers prevented anyone from driving on the highway. The next village was abandoned. It once belonged to a corrupt minister in the Hafiz Assad government and its extremist citizens were an active part of the revolutionary forces. There were also several small university campuses.

As we approached Bosra, the military checkpoints became more frequent and more demanding of ID. Members of the Free Syrian Army still exist here but live as normal citizens. One is never sure if they decide to become active again.

ANCIENT CITY of BOSRA

Bosra is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Daraa District and geographically being part of the Hauran region.

Bosra had a population of 19,683 (2004) and 33,839 in the metropolitan area. Bosra’s inhabitants are predominantly Sunni Muslims.

Bosra has an ancient history and during the Roman era, it was a prosperous provincial capital and Metropolitan Archbishopric, under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. It continued to be administratively important during the Islamic era but became gradually less prominent during the Ottoman era. It also became a Latin Catholic titular see and the episcopal see of a Melkite Catholic Archeparchy. Today, it is a major archaeological site and has been declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

HISTORY

The settlement was first mentioned in 14th-century BC Egyptian documents. Bosra was the first Nabatean city in the 2nd century BC. The Nabatean Kingdom (great traders rich from the frankincense trade from Oman and the founders of Petra, Jordan) was conquered by Cornelius Palma, a general of Trajan, in 106 AD.

Roman and Byzantine era. The Romans renamed it Nova Trajana Bostra as the capital of the Roman province of Arabia Petraea. The city flourished and became a major metropolis at the juncture of several trade routes on the Via Traiana Nova, a Roman road that connected Damascus to the Red Sea. It became an important center for food production and during the reign of Emperor Philip the Arab, Bosra began to mint its own coins. The two Councils of Arabia were held at Bosra in 246 and 247 AD.

By the Byzantine period beginning in the 5th century, Christianity became the dominant religion. The city became a Metropolitan archbishop’s seat and a large cathedral was built in the sixth century. Bosra was conquered by the Sasanian Persians in the early seventh century but was recaptured during a Byzantine reconquest.

Islamic era. Bosra played an important part in the early life of Muhammad. The Rashidun Caliphate captured the city from the Byzantines in the Battle of Bosra in 634. Throughout Islamic rule, Bosra would serve as the southernmost outpost of Damascus, its prosperity being mostly contingent on the political importance of that city. Bosra held additional significance as a center of the pilgrim caravan between Damascus and the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina, the destinations of the annual Hajj pilgrimage. Early Islamic rule did not alter the general architecture of Bosra, with only two structures dating to the Umayyad era (721 and 746) when Damascus was the capital of the Caliphate. As Bosra’s inhabitants gradually converted to Islam the Roman-era holy sites were utilized for Muslim practices.

After the end of the Umayyad era in 750, major activity in Bosra ceased for around 300 years until the late 11th century. Under Seljuk’s rule (1076), the Roman theatre was transformed into a fortress. After the Burid dynasty came to power in Damascus, the Muslim nature of the city increased with the construction of many Islamic edifices: the restoration of the Umari Mosque, which had been built by the Umayyads in 721; the smaller al-Khidr Mosque in 1134, a madrasa constructed alongside the Muslim shrine honouring the mabrak an-naqa (“camel’s knees”), which marked the imprints of the camel the prophet Muhammad rode on when he entered Bosra in the early 7th-century.

A golden age of political and architectural activity in Bosra began during the reign of Ayyubid Sultan al-Adil I (1196–1218). Eight large external towers were built in the Roman theatre-turned-fortress from 1202 to 1253. The two northern corner towers alone occupied more space than the remaining six. After al-Adil died in 1218, his son Salih Ismail used the city as his base when he claimed the sultanate in Damascus between 1237–38 and 1239–45.

Ottoman era. In 1596 it had 75 Muslim households and 27 bachelors, and 15 Christian households and 8 bachelors. Taxes were paid on wheat, barley, summer crops, fruit- or other trees, goats and/or beehives and water mills.

Ecclesiastical History. As the capital of the late Roman province of Arabia Petraea, Bosra was its Metropolitan Archbishopric, under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. Later it also became a Latin titular see. The Latin apostolic succession was ended, but the city was made eponymous of the Melkite Catholic Archeparchy of Bosra-Hauran, which has its actual Marian cathedral seen in Khabab city.

The Latin archdiocese was nominally restored as a Latin Metropolitan titular archbishopric in the 18th century. It was vacant for decades, having had several archiepiscopal incumbents of the highest, Metropolitan rank dating from 1734 to 1975 including two from the US (New Orleans and Chicago).

Modern era. Today, Bosra is a major archaeological site, containing ruins from Roman, Byzantine, and Muslim times, its main feature being the well-preserved Roman theatre. Every year there is a national music festival hosted in the main theatre.

Significant social and economic changes have affected Bosra since the end of the French Mandate in 1946. Many of its residents have found work in the Persian Gulf states and Saudi Arabia, sending proceeds to their relatives in Bosra. Social changes together with increased access to education have largely diminished the traditional clan life.

During the presidency of Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000), Bosra and the surrounding villages were left largely outside of government interference.

The Civil War involved Bosra. Starting in October 2012, and continuing to January when the citadel was used by the army to shell the town daily. After February 2014 the city was under the control of the Syrian Army but by March 2015, the rebels had reseized the town. Bosra was recaptured by the Syrian Arab Army in July 2018, as part of the ongoing Daraa Offensive, which has involved the surrender and/or reconciliation of many rebel groups in the area.

MAIN SIGHTS

Of the city that once counted 80,000 inhabitants, there remains today only a village settled around the ruins. Nabatean and Roman monuments, Christian churches, mosques and Madrasahs are present within the half-ruined enceinte of the city.

This was Mekhlas’ first visit to Bosra in ten years. It was impossible to visit during the Civil War and access has only been possible in the last 3 months. Up to one month ago, military escorts were necessary to see the ruins.

Roman theatre. Constructed in the 2nd century probably under Trajan, it is the only monument of this type with its upper gallery in the form of a covered portico that has been integrally preserved. It was fortified between 481 and 1231.

Cross the moat on a stone bridge to enter the corridor of the fortress that makes four 90° turns. This massive stone fortress completely encompasses the theatre. It has several large square bastions.

The theatre is almost completely intact, easily the most complete Roman theatre in the world. It held 15,000 in three tiers of still intact seats accessed from multiple arcades, so efficient that the theatre could be emptied in 15 minutes. These arcaded stairs have wonderful successive arches. Columns topped by capitals are still present on about ¼ of the top circumference.

The most spectacular part is the completely intact three-story stage. As the theatre was half full of sand until about 1930, all but four of the 30 white limestone columns with Corinthian capitals on the first level behind the stage are present. It is easy to see how they provided a contrast to the black basaltic rock and improved the acoustics of the theatre. Only 4 small column remnants remain on the second story and none on the third. The stage has many niches that once held statues.

The large semi-circular orchestra pit has original stone pavers, but now with two bomb scars.

Nova Trajana Bostra Roman Town. With several intact buildings, it is one of the better Roman ruins in the world. The 1.3km Cardo Maximus bisects the city and has an almost complete Abbatean Gate. Walking along the Deccamanos (secondary street), pass the columned sports hall and huge bath with a room with possibly the only (almost) intact domed ceiling in any Roman ruin. After the theatre, the most spectacular building is the small nymphaeum with an intact stone roof and lovely niches topped with scallop shell design.

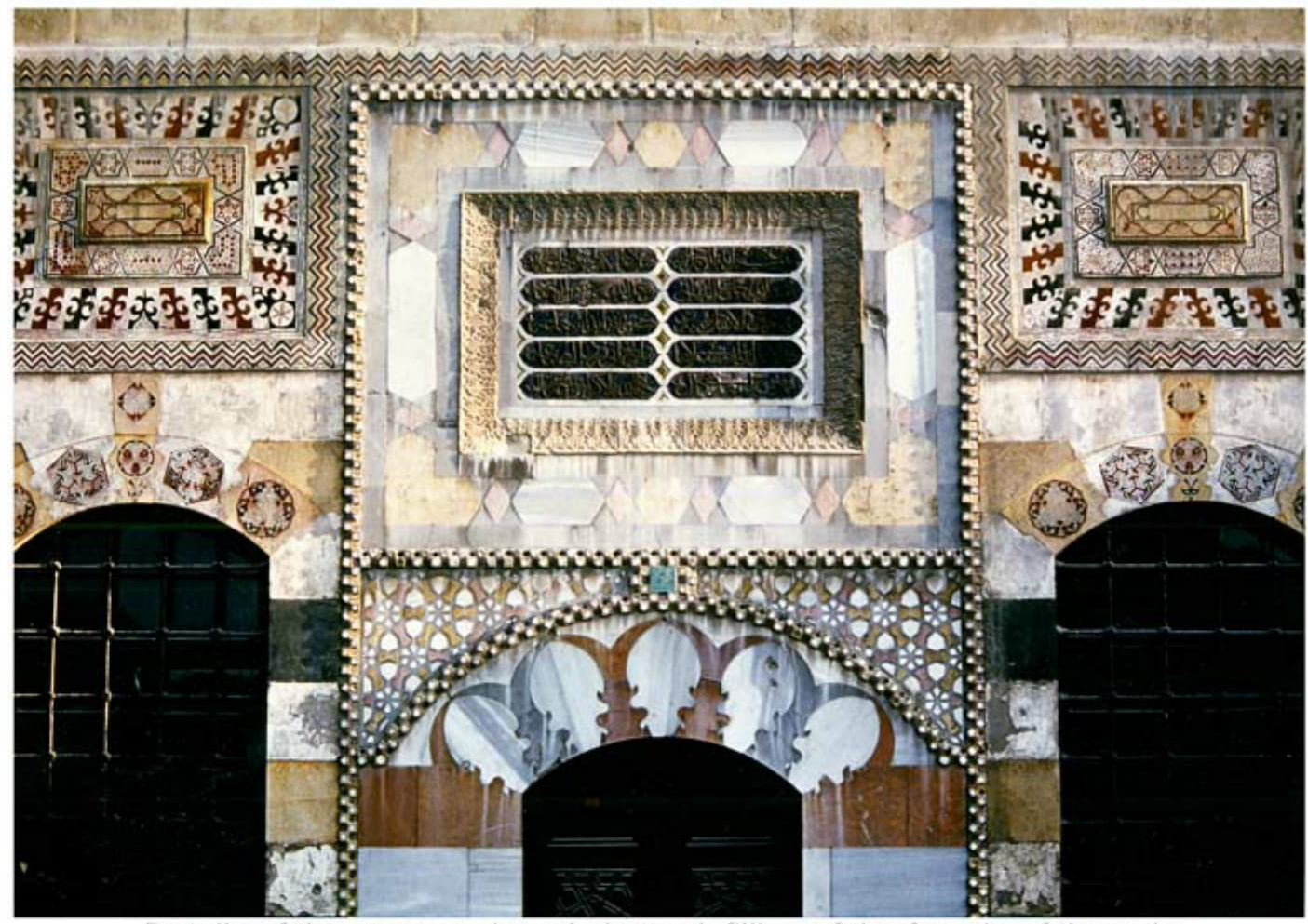

The large Arab town abuts the Roman town. The Al-Omari Mosque of Bosra is one of the oldest surviving mosques in Islamic history. It was not open but we wondered the cobble streets between mostly intact ruined walls.

Christian Churches. Founded by the Nestorian bishops in 245 AD, its centre was in the Dead Cities in NW Syria between Aleppo and Idlib. They built two large churches in Bosra. The Holy Cross Church has a central plan under a large dome supported by columns, some of which are still intact. Apses flanked by 2 sacristies exerted a decisive influence on the evolution of Christian architectural forms, and to a certain extent on Islamic style. Mosaics and faint frescoes are on some of the walls.

Cistern. Dating from Arab times and 126m by 158m, this huge cistern still had a fair amount of water in it.

Close by are the Kharaba Bridge and the Gemarrin Bridge, both Roman bridges.

Khabab. This is a Christian town of about 9,000, 1,500 of them from Mukhles’ extended family. He can trace his family tree here back to the 15th century arriving from Yemen. His family moved from here to Qneitra in the Golan Heights and moved back in 1968. The mansion and church belonging to the Metropolitan Archbishops is here. Because it was Christian, there is no damage from the Civil War. We stopped in at the house of his 96-year-old uncle, cousin and his family. Syrian hospitality is lovely – coffee, home dried raisins and date cookies.

On the return trip to Damascus, the traffic was backed up for miles due to all the military checkpoints. Thankfully we were able to bypass most of in the left lane.

ANCIENT CITY of DAMASCUS.

Is the historic city centre of Damascus, Syria. The old citY is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, and contains numerous archaeological sites, including some historical churches and mosques. Many cultures have left their mark, especially Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic. In 1979, the historical center of the city, surrounded by walls of the Roman era, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. In June 2013, UNESCO included all Syrian sites on the list of World Heritage in Danger to warn of the risks to which they are exposed because of the Syrian Civil War.

History

Origins and founding. Lying on the south bank of Barada River, the ancient city was founded in the 3rd millennium B.C. The horizontal diameter of the oval is about 1.5 km (0.9 mi) which is known as Damascus Straight Street, while the vertical diameter (Latin: Cardus Maximus) is about 1 km (0.6 mi). With an approximate area of 86.12 hectares (212.8 acres; 0.86 km2), the ancient city was enclosed within a historic wall of 4.5 km (2.8 mi) in the circuit that was mainly built by the Romans, then fortified by the Ayyubids and Mamluks.

The first mentioning of Damascus was as “Ta-ms-qu” in the second millennium BC, it was situated in an Amorite region in the middle of a conflict zone between the Hittites and Egyptians. The city exercised tributary until the emergence of the Sea Peoples in 1200 BC whose raids helped to weaken their arch rivals. Consequently, the Semitic Arameans managed to establish the independent state of Aram-Damascus (11th century – 733 BC), naming the main city as ‘Dimashqu’ or ‘Darmeseq’.

Historical timeline. Throughout its history, Damascus has been part of the following states:

| c. 2500–15th century BC, Canaanites 15th century BC–late 12th century BC, New Kingdom of Egypt late 12th century BC–732 BCE, Aram-Damascus 732 BC–609 BC, Assyria 609 BC–539 BC, Babylonia 539 BC–332 BC, Persian Achaemenid Empire 332 BC–323 BC, Macedonian Empire 323 BC–301 BC, Antigonid dynasty 301 BC–198 BC, Ptolemaic Kingdom 198 BC–167 BC, Seleucid Empire 167 BC–110 BC, Ituraea (Semi independent from Seleucids) 110 BC–85 BC, Decapolis (Semi independent from Seleucids) 85 BC–64 BC, Nabataea 64 BC–27 BC, Roman Republic 27 BC–395 AD, Roman Empire 476–608, Byzantine Empire 608–622, Sassanid Persia 622–634, Byzantine Empire (restored) 529–634, Ghassanids 634–661, Rashidun Caliphate 661–750, Umayyad Caliphate | 750–885, Abbasid Caliphate 885–905, Tulunids 905–935, Abbasid Caliphate (restored) 935–969, Ikhshidids 970–973, Fatimid Caliphate 973–983, Qarmatians 983–1076, Fatimid Caliphate (restored) 1076–1104, Seljuq Empire 1104–1154, Burid dynasty 1154–1174, Zengids 1174–1260, Ayyubids 1260 March–August, Mongol Empire 1260–1521, Mamluk Sultanate 1516–1918, Ottoman Empire 1918–1920, Occupied Enemy Territory Administration 1920 March–July, Arab Kingdom of Syria 1920–1924, State of Damascus under the French Mandate 1924–1946, French Mandate of Syria 1946–1958, Syrian Republic 1958–1960, United Arab Republic 1960–present, Syrian Arab Republic |

On the return trip to Damascus, the traffic was backed up for miles due to all the military checkpoints. Thankfully we were able to bypass most of in the left lane.

MAIN SITES

Damascus has a wealth of historical sites dating back to many different periods of the city’s history. Since the city has been built up with every passing occupation, it has become almost impossible to excavate all the ruins of Damascus that lie up to 2.4 m (8 ft) below the modern level.

The historic city is in the shape of an oval with a horizontal diameter of about 1.5 km and is known as Damascus Straight Street, a Roman street (Decumanus Maximus or east-west main street). It was referred to in the conversion of St. Paul in Acts 9:11. Today, it consists of the street of Bab Sharqi and the Souk Medhat Pasha, a covered market. It is filled with small shops and leads to the old Christian quarter of Bab Tuma (St. Thomas’s Gate). The vertical diameter (Cardus Maximus) is about 1 km. The approximate area is 86.12 hectares (212.8 acres; 0.86 km2),

The City Wall and Gates. The ancient city was enclosed within a historic wall of 4.5 km (2.8 mi) in the circuit mainly built by the Romans, and then fortified by the Ayyubids and Mamluks. It has seven historical gates.

House of Saint Ananias. Legend relates that Paul after leaving Jerusalem was initially persecuting Christians. In Damascus, Jesus appeared as an apparition, struck down Paul and blinded him, then asked “Why are you persecuting me?” Paul fasted for 3 days after which Ananias baptized Saul (who became Paul the Apostle) in this ancient underground chapel that was the cellar of Ananias’s house.

After that, Paul preached in the name of Jesus in Damascus for 2 years and then travelled through Turkey and Greece finally reaching Rome where he was beheaded.

At the end of Bab Sharqi Street, is a vaulted structure below street level. Many people report having powerful energy whenever they enter it. Three bas reliefs in the apse relate to the story.

We walked along the Straight Street, now a fairly narrow, one-way driving street with endless traffic. In the narrow area between the street and sidewalk are the remnants of many original Roman columns. Ground scanning radar has shown there are 653 columns approximately 6m below street level. There are many interesting things on the street: crumbling palaces, a park commemorating the 1915 Syrian Genocide Sayfo (Armenians killed by Turks in Syria), a Roman triumphal arch and a 13th-century minaret with no mosque.

Maktab Anbar, a mid-19th-century Jewish private mansion, was restored by the Ministry of Culture in 1976 to serve as a library, exhibition centre, museum and craft workshops. The haremlik is another spectacular example of a paradise garden with

Cathedral of the Dormition of Our Lady, the Catholic cathedral of Melkite Greek Church.

Citadel of Damascus was built (1076–1078) and (1203–1216) by Turkman warlord Atsiz ibn Uvaq, located in the northwest corner of the Old City.

Azm Palace, built in 1749 as a residence for the Ottoman governor of Damascus As’ad Pasha al-Azm, it is a great example of Damacean domestic architecture. Covering 5,200 m2, it took 800 craftsmen two years to construct. All the stone is yellow/black/white and has inlaid marble designs on the arches, arches over the windows and façades. The haremlik is built as “gardens of paradise” as the women were unable to leave – trees, fountains. The summer house on the south had high peaked roofs and wind towers and the winter house faced the sun. The salamlik was for men only and hosted visitors. Since 1955 it has been a museum.

The Umayyad Mosque (Grand Mosque of Damascus), is one of the largest mosques in the world and also one of the oldest sites of continuous prayer since the rise of Islam. On this site previously was an Aramaic temple from 1000 BC, the Roman Temple of Jupiter from the 2nd century and in 314, Constantine built a Byzantine church here called St John the Baptist. A shrine in the mosque is said to contain the body of St. John the Baptist brought here from Jerusalem by Helen, Constantine’s wife. The Muslims peacefully occupied the church in 633 and in 665, half the church was converted into a mosque. In 705, the church and Temple of Jupiter were destroyed and the old stones were used to build the rest of the mosque.

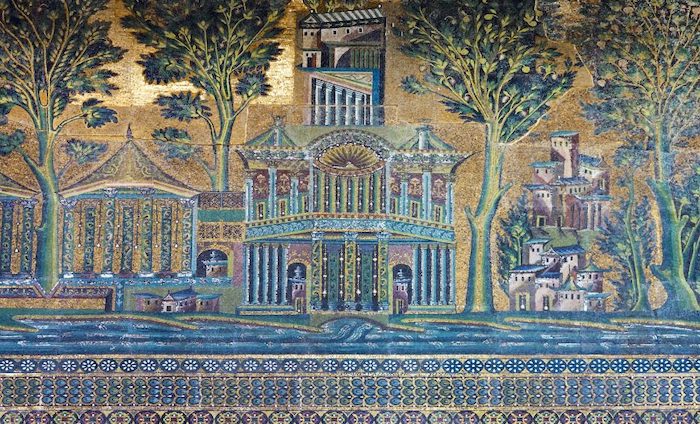

Enter the huge courtyard, the west wall area has marvellous green/gilded mosaics full of citrus trees, palaces and buildings. The mosaics cover the upper wall, under the arches and the octagonal treasure house on the edge of the courtyard. Also in the courtyard are a clock dome and a dome over the fountain in the middle of the courtyard.

The mosque is gigantic – 157m long, 97m wide and with 3 naves as in a church, one of them for the women. The dome sits in the middle (like a Latin Cross) with the intricate mihrab and carved marble minbar.

On the outside, the entire west wall is from the original Roman temple with a Roman gate embedded in the wall. The 12th-century Jesus minaret is where Jesus is supposed to appear in the “End of Days”. The Al-Arous (bride) minaret has an astronomical clock.

A large courtyard on the north has multiple limestone Roman columns and the original 4th-century Christian bell tower, now a minaret. This courtyard fronts the mausoleum.

Mausoleum of Saladin, built in 1196, is the resting place and grave of the medieval Muslim Ayyubid Sultan Saladin are located in the gardens just inside the west courtyard of the mosque. Saladin defeated the Crusaders in 1186 and died 7 years later. In 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany built and empty marble sarcophagus in the shrine.

Temple of Jupiter was built by the Romans, beginning during the rule of Augustus and completed during the rule of Constantius II. Previously a temple was dedicated to Hadad-Ramman, the god of thunderstorms and rain. At the entrance of Al-Hamidiyah Souq.

Al-Hamidiyah Souq, built (1780–1884) during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid I, the largest and the central souk in Syria, located inside the old walled city of Damascus next to the Citadel and across the square from the Um. The souq is about 600 meters long and 15 meters wide and is covered by a 10-meter tall metal arch.

Bakdash Ice Cream Shop. In the souq, it dates from 1895 – the soft ice cream is scooped out of tubs and served with sliced pistachio nuts.

Hammams. Public baths (ḥammāms) in Damascus started during the Umayyad era, while some historians date them back to the Roman era. In 1175, there were 77 baths and in 1250, 114 baths, increasing to 365 during the Ottoman era, then decreased drastically to 60 baths in the late nineteenth century AD. Today, however, the number of baths in full operation is barely 20, the most famous of them is the “Nour al-Din al-Shahid” bath in the Al-Buzuriyah Souq.

Threats to the future of the Old City

Due to the rapid decline of the population of Old Damascus (between 1995 and 2009 about 30,000 people moved out of the old city for more modern accommodation), a growing number of buildings are being abandoned or are falling into disrepair.

In spite of the recommendations of the UNESCO World Heritage Center:

In 2007, the Old City of Damascus as one of the most endangered sites in the world.

In October 2010, the Global Heritage Fund named Damascus as one of 12 cultural heritage sites most “on the verge” of irreparable loss and destruction.

National Museum. Built in 1935 by the French, it has 5 parts each covering a part of Syrian history but only the “classic” portion has been open for the last several years. The entrance is the portal of the main gate of a palace from the desert used for hunting, as a caravanserai and a brothel. There are several lovely mosaics including the “glory of the earth” mosaic. Other highlights are many artifacts of the Palmyrene civilization (priests with round hats, the Tomb of Yarhai, women were high status) and a Phoenician sarcophagus.

Hafez Al Assad statue. Dating from 1986, this 3m tall concrete statue is painted gold and sits in a park. It is backed by a 2015 monument to the Youth of Syria with a Syrian flag.

Tekkgeh Sulamanea. This was a caravanserai for pilgrims on the way to Mecca. It has a mosque in the middle, 2 minarets, and surrounding the courtyard, domed rooms behind an arcaded front. It was 2 km outside the city walls to prevent disease and revolutionary thoughts from spreading inside the city.

Tekkgeh Selimyeh. Another pilgrimage hotel, it has no mosque.

Day 3 Maaloula, Aleppo

We had an early start at 07:30 as we had a long drive and many things to do and see.

In north Damascus, we passed Ishlbub, an Aliwaite village clinging to a mountainside that was heavily bombed in the war.

SAIDNAYEH. This is a Christian village just north of Damascus. The high point (the convent) is 1900m elevation. It snows every year.

Saidnayeh Prison. We passed this prison before the village that holds about 11,000 ISIS, communists, Nusra (Al Qaeda soldiers from Libya, Egypt, Kuwait, Turkey, Tunisia, Syrians) and other prisoners of war.

Saidnaya Convent. This Byzantine convent was built by Justinian in the 6th century AD. Legend states that Justinian was hunting, saw a deer that ran away and reappeared as an image of the Virgin Mary. She commanded Justinian to build the convent on an improbable rocky outcrop. His engineers said it was impossible. Mary reappeared and “magically”, the foundation of the convent appeared. This story is told on a series of small paintings over the brass door of the church. Inside (which unfortunately is always locked) is a 1st-century icon of the Virgin Mary. The convent is a white limestone complex.

Statue of Jesus. In the NM “Religious Monuments” series, this relatively new concrete statue sits on a pedestal of stones. It is painted bronze.

The drive north traversed a plateau, 1600m above sea level. The west skyline was a 49km long mountain ridge called Qlamoun Mountain with a dramatic cliff on the east side.

MAALOULA (pop 2,762 in 2004, about 4000 today – ⅔ Christian, ⅓ Muslim)

Maaloula is located 56 km to the northeast of Damascus and built into the rugged cliffs of Qlamounn Mountain at an altitude of more than 1500 m. During the summer, the population increases to about 10,000, due to people coming from Damascus for holidays. Half a century ago, 15,000 people lived in Maaloula.

Religiously, the population consists of both Christians (mainly members of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch and the Melkite Greek Catholic Church) and Muslims. For the Muslim inhabitants, the legacy is all the more remarkable given that they were not Arabised, unlike most other Syrians who were not only Islamised over the centuries but also adopted Arabic and shifted to an Arab ethnic identity.

Language. With two other nearby towns al-Sarkha (Bakhah) and Jubb’adin, Maaloula is the only place where a Western Aramaic language is still spoken, which it has been able to retain amidst the rise of Arabic due to its distance from other major cities and its isolating geological features. However, modern roads and transportation, as well as accessibility to Arabic-language television and print media – and for some time until recently, also state policy – have eroded that linguistic heritage.

As the last remaining area where Western Neo-Aramaic is still spoken, the three villages represent an important source for anthropological linguistic studies regarding first-century Western Aramaic. According to scholarly consensus, the language of Jesus was also a Western Aramaic dialect; more specifically the Galilean variety of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic.

Despite frequent misstatements in the media, however, the Neo-Aramaic spoken in Maaloula, Bakhah and Jubb’adin is no longer identical to the dialect which Jesus of Nazareth spoke. Firstly it evolved from a separate Western Aramaic dialect from the Galilean dialect of Jesus, and secondly, as a part of natural language evolution, it has undergone significant changes since the first century AD (~2,000 years ago) in a similar way that Old English (~1,000 years ago) and even Middle English (~500 years ago) may be unintelligible to Modern English speakers.

War in Syria. Maaloula became the scene of battle between Al-Qaeda-linked jihadist Al-Nusra Front and the Syrian Army in September 2013. Syrian rebels took over the town on October 21. Around 13 people were killed, with many more wounded. On October 28, government forces recaptured the town.

Maaloula was taken over by the al-Nusra Front again on December 3, 2013. The Front took 12 orthodox nuns as hostages. The nuns were moved between different locations and ended up in Yabroud where they stayed for three months. Then, officials from Qatar and Lebanon negotiated a deal for their release. Those negotiations produced an agreement on a prisoner exchange under which around 150 Syrian women detained by the government were also freed. After the nuns were freed on the 9th of March 2014, they stated that they were treated well by their captors.

On 14 April 2014, with the help of Hezbollah and SSNP, the Syrian Army once more took control of Maaloula. This government success was part of a string of other successes in the strategic Qalamoun region, including the seizure of the former rebel bastion of Yabroud in the previous month.

Monasteries. There are two important Greek Catholic monasteries in Maaloula.

Saint Sarkis Monastic Complex. One of the oldest surviving monasteries in Syria. It was built on the site of a pagan temple and has elements that go back to the fifth to sixth-century Byzantine period. Saint Sarkis is the Assyrian name for Saint Sergius, a Roman soldier who was beheaded by Diocletian for his Christian beliefs.

Wood built into the stone walls was carbon-dated to 2000 years old. The 325 Council of Nicea was attended by the bishop of this church. At the council, it was decreed that animal sacrifices were prohibited in Christian churches. Altars changed from have a rim decorated with animals and a hole for blood drainage to a flat surface. The very special altar in this church is a large half-oval with a rim, implying that its origin is before 325. This monastery still maintains its solemn historical character. The priest is an old friend of Mikhlos. In the war, he left for Lebanon but has now returned to the church.

The monastery has two of the oldest icons in the world, one depicting the Last Supper that was stolen by ISIS and destroyed. A 17th-century copy of this is in the church – the table is a semi-circle and Jesus sits on the left side, not the middle. John has his head on Jesus’ lap.

Enter the complex courtyard. The church has 2 side aisles and is rough stone construction.

I was let off at the top of the canyon discussed below. It is a slot canyon that narrows to about 1.5m and I quite twisty with high walls. It widens out just before the town.

Saint Thecla Monastic Complex. This monastery holds the remains of Thecla, which the second-century Acts of Paul and Thecla accounts a noble virgin and pupil of St. Paul. According to later legend not in the Acts, Thecla was being pursued by soldiers of her father to capture her because of her Christian faith. She came upon a mountain, and after praying, the mountain split open and let her escape through. The town gets its name from this gap or entrance in the mountain. However, there are many variations to this story among the residents of Maaloula. The small square building sit on the north rim of the canyon and is distinguished by a large cross visible from the town below..

There are also the remains of numerous monasteries, convents, churches, shrines and sanctuaries. Some lie in ruins, while others continue to stand, defying age. Many pilgrims come to Maaloula, both Muslim and Christian, and they go there to gain blessings and make offerings.

Virgin Mary statue. The people of Maaloula celebrated as a new statue of the Virgin Mary was erected in its centre, replacing the figure destroyed in rebel attacks in 2013. On 13 June 2015, Syrian officials unveiled the new statue of the Virgin Mary, draped in a white robe topped with a blue shawl, her hands lifted in prayer. The fibreglass figure stood at just over 3 metres (10 feet) tall and was placed on the base of the original statue. The statue is titled Lady of Peace.

I returned to Beirut on November 9 after a long 350km drive from Palmyra. I stayed in the same wonderful hotel as I originally stayed in and was served my ideal breakfast. In the morning it was a 3-hour drive to Beirut to catch my flight to Ankara Turkey and my van. I was missing her – it had been one whole month of tours to Iran, Turkmenistan and Syria.