Turkey – Southeast Anatolia (Diyarbakir, Gaziantep, Mardin, Batman, Urfa) December 14-17, 2019

From Kurdistan, Iraq, I turned west to drive along the Iraq border. It was the first sunny day in weeks of endless rain or snow. The interesting landscape was a relatively flat ancient lava field – initially black then red/white basalt boulder fields. Small fields had been laboriously cleared of all the rock.

There are still many military checkpoints – “This is dangerous country”.

ZEYNEL ABIDIN MOSQUE COMPLEX and MOR YAKUP (Saint Jacob) CHURCH (15/04/2014)

These are testimonies of the coexistence of different religions for centuries in Nusaybin (ancient Nisibis). Mor Yakup Church is situated just 100m to the east of Zeynel Abidin Mosque, and both lie about 250 meters from the Syrian border.

Mor Yakup Church. Mor Yakup was a prominent Assyrian saint born in Nisibis (now Nusaybin), and was brought up there. He was appointed the bishop of Nisibis in 309 and founded the Nisibis cathedral in 313. Nisibis was the major commercial and political centre in the East Roman Empire and the border of the Roman and Persian Empires. He and his student Mor Afrem (Saint Ephrem), a great ascetic, teacher and hymn writer, were present at the First Council of Nicaea (modern İznik province in Turkey) in 325. After they returned to Nusaybin, they built the Nisibis School where theology, philosophy, logic, literature, geometry, astronomy, medicine and law were subjects. The school contributed to the spread of Christianity in Mesopotamia via the students who were educated there.

The present church, one of the oldest religious structures of upper Mesopotamia dating to the 4th century was originally a Byzantine baptistery converted into a church. The most striking feature of the east side is wall decorations – a frieze on the door’s arches, apses and on the western arch.

The west side door arches also have excellent ornaments. A Greek inscription states “This baptistery was built with the contribution of priest Akepsyma in 571 (359/360), when Volagesus was metropolitan. Let them be remembered before God”. It is the first inscription mentioning the word “baptistery”.

The dome is dated to 1872. The crypt has a sarcophagus believed to belong to Mor Yakup.

Zeynel Abidin Mosque Complex. Made of rough stone, this consists of a mosque, 1956 minaret, 1159 shrines of both Zeynel Abidin and his sister Sitti Zeynep (13th generation grandchild of the Prophet Muhammad), fountains, madrasah, graveyard and new apteshane. Construction dates to the 12th century. The mihrab and minbar are new. The building was renovated in later periods and lady’s worship was added to the community section.

Both have been significant centres of education and science. Nusaybin has been under Muslim control since the Arab conquest of 640. According to Syriac sources, the money required for the construction of Zeynel Abidin Mosque was given by two Christian priests with the idea of spending money on the way to God. The survival of the church for 1600 years is a testament to the Muslim respect for Mor Yakup. Both were built on land belonging to the same foundation with common cemeteries, shrines, madrasahs and schools.

MIDYAT

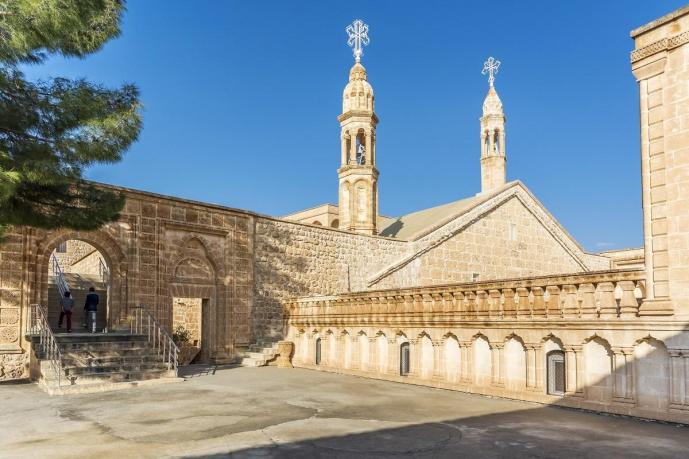

Mor Gabriel Monastery (Saint Gabriel) is one of the oldest Christian monasteries in the world and is Syriac Orthodox. It was founded in 397 by two monks Mor Shmuel and his apprentice Mor Shemun on the Tur Abdin plateau near Midyat. According to legend, Shemun saw an Angel in a dream and this Angel told him to build a church in a place marked with three big stones.

The present monastery buildings were built at different times to meet the needs of the increasing number of monks with donations of the Roman and Byzantine Emperors like Honorius, Arcadius, Theodosius II and Anastasius. Now the monastery consists of two parts: the lower historic and the upper new annexes added in the last half-century.

The main Church was built in 512 but was under renovation when I was there. The mosaics in the ceiling and on the floor of the altar are faded.

The octagonal “Dome of Theodora” was used as a dining room for a long time. It has a great stone and brick dome, the same height as the church. A scale model of the monastery built using wooden matches took 5 years to make.

While the main church was being renovated, the monks prayed in the Church of the Virgin Mary built in the 6th century. It was fully renovated in 1991 with paintings of Christ on the walls done in 1992. The crypt (Beth Qadishe, “the House of Saints”) has over 12 000 relics of saints and martyrs.

This monastery is surrounded by a one-kilometre, 6m high wall constructed from the red/white tuff. The grounds have neat tilled fields full of pistachio and fruit trees and the entrance lane is lined by lovely pine trees. It has been beautifully restored with a nice terrace and carved stone banisters.

Presently, a bishop, 3 monks, and 14 nuns live in the monastery. They pray 7 times a day, three times together. It is also a school with 20 students and a total of 60 residents. See it on a guided tour. TL5

MARDIN (pop 764,000)

The city is located on the slope of a steep hill that culminates in a rocky knob with some fortress ruins. It looks south to the Mesopotamian plains. The old city is connected by stairways and steep lanes radiating off the main cobbled street. The north side of the mountain is abandoned terraces.

According to hearsay, the history of the city dates as far back as the Flood. The city lived under the rule of the Hurri-Mitani, Hittites, Surs, Babylonians, Persians, Arabs, and the Seljuk Turks. Later, the Mardin branch of the Artuklu Kingdom called “Tabaka Ilgaziyye” was established and the city flourished during this time.

The Mardin Cultural Landscape is a tentative WHS (25/02/2000). Cultural landscapes — cultivated terraces on lofty mountains, gardens, and sacred places … — testify to the creative genius, social development, and imaginative and spiritual vitality of humanity. They are part of our collective identity.

Houses in Mardin, reflecting all features of a closed-in lifestyle, are surrounded by 4-meter-high walls and isolated from the street. These walls also protect from harsh climatic conditions. Houses have separate sections for males and females and mostly have no kitchen. The most important feature of these houses is the stone craftsmanship called “Midyat Work”. Since in a volcanic area, the basic input used in local architecture is easily workable calcareous rock. Doors, windows, and small columns are dressed with arches and various motifs. Above the house doors are carved pictures of the Kaaba if the owner has made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and the door knockers have a distinctive form resembling the beaks of birds. Often the lanes run through arched tunnels beneath the upper floors of houses. Relief carvings of animals and fruit lend the city a dream-like character.

Syrian Orthodox gold and silver smiths whose work is famous throughout the country still practice their craft here, their workshops side by side with those of Muslim copper smiths. Along with the buildings themselves, it is to be hoped that this living culture can also be preserved.

Mardin is located in the area where the Southeastern Taurus Range meets the Arabian platform to the south. The area called “Mardin-Midyat Passage” constitutes a large part of the territory of the province. Mardin is on the rail and highway routes connecting Turkey to Syria and Iraq.

After the completion of the GAP Project, 100,000 hectares of land were brought under irrigation in the Mardin area. Newly irrigated areas mainly grow cotton that is processed by enterprises in the Organized Industrial Zone. Besides flour products, fruit processing, and seed production, Mardin also processes its local grapes. Phosphate-containing fertilizers are provided by the fertilizer industries in the province.

Mardin Museum. The museum is housed in the former patriarchate constructed in 1895 by the Patriarch of Antakya, Ignatios Benham Banni. Now restored to its original condition, the building houses collections dating from 4000 BC up to the present day and representing the Assyrian, Urartian, Hellenistic, Persian, Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk, Artuklu, and Ottoman periods. Pottery, seals, cylinder seals, coins, lamps, figurines, teardrop bottles, and jewelry are among the many exhibits.

Mardin Bazaars. The single main street is one big shopping district. Several bazaars come off it.

Other Sights in the City

Kasimiye Medresse, Kasim Pasa Medresse, Zinciriye Medresse, and Grand Mosque are important historical sites around the city.

Sights in the Surrounding Area

Zeynel Bey Mausoleum. Built in the 15th century, it is decorated with blue tiles. Sultan Isa Medresse. Dating from 1385, it is a beautiful Turkish monument with its magnificent carved portal.

Ulu (Grand) Mosque with its well-decorated minaret is in Kiziltepe.

Dara site is one of the most interesting discoveries of the latest excavations near Mardin. It’s located on the way to Nusaybin near the Syrian border.

Hasankeyf. Ruins of the ancient 12th-century capital of the Artutids. 21 kilometers south of Mardin, with the 13th century Ulu Mosque with its fine mihrab relief and beautifully decorated portal. Hasankeyf will be completely flooded when the nearby dam is completed, a part of the GAP Project.

Deyr’ul Zafaran Monastery is a Syriac monastery 9 kilometres to the east of Mardin, built in the 9th century and was used until 1932. One of the biggest of many monasteries in the region, Deyr’ul Zafaran has 52 Syriac Patriarchs buried here. The secret section for worshipping called “mahzen” is the oldest part of the monastery. The monastery was enlarged with additional sections built later. Around the structures which form a trinity with Deyr’ul Zafaran, the Church of Virgin Mary and Mar Yakup Monastery, there are three fortresses built to protect the trinity.

DIYARBAKIR

The walls and gates of the town together with the Ula Cami (Great Mosque) usually share the construction style of being built with black basalt stones decorated with white inlays.

Ten-Eyed Bridge (Dicle Bridge or Ongözlü Köprü). It crosses the Tigris 2kms south of Diyarbakir (Dicle is the old name of the Tigres). It replaced an earlier bridge in the 11th century and has been restored many times. The north end stops at a wall that supports the road above and the other end terminates in a long set of steps. With ten arches and 171m long, it was built with basalt boulders and bricks from a quarry 100 km away from Diyarbakir. The deck over the first 5 arches averages 10m wide and others 5.45-6.24m wide. It has flood splitters on the upstream side and the walls are capped with triangular basalt stones.

DIYARBAKIR FORTRESS and HEVSEL GARDENS CULTURAL LANDSCAPE A combined World Heritage Sites (2015).

Diyarbakir Fortress. A huge fortress with 5.5kms long and 8m high walls, some intact and some ruined, completely encircle a part of the modern city. I wandered into the south end of the fortress but it is a military zone and full of new construction. The mosque was here. Hazreti Suleyman Camii (Mosque of the Citadel) was built between 1155-69 and has a tall, square minaret without balconies and no white decoration.

Hevsel Gardens. Described as the garden of Eden, Hevsel is on fertile lands on the banks of the Tigris under the city walls. The fruit trees and vegetable gardens have supplied the city for a thousand years.

Diyarbakir Great Mosque. Enter a large courtyard with a variety of columns and arches, some marble and some limestone, with ornate capitals and friezes. The mosque is large – narrow and long with 2 sets of basalt columns and arches. The mihrab is very simple black/white basalt.

Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı Museum (1910-56). A poet and writer from Diyarbakir, this was his house in the old city. Enter a courtyard of black basalt walls to see posters with information, photos and personal effects. Zero English and I left only knowing that he was probably a musician. Free

When leaving Kurdistan, an engine check light came on indicating a problem with the exhaust/catalytic converter system. Thankfully it was not urgent as I could not find a VW dealer until Diyarbakir. It turned out to be a leak in one of the hoses and was covered by warranty. I had dinner and slept in the lot. They even had a shower!

Only one young woman spoke much English.

The job seemed to take forever – 3½ whole days to figure out, but I parked in the front of the dealership for 2 nights and slept in the garage for one. I played a lot of bridge, did a lot of work on the website and organized business in my life.

The garage has a cafeteria and everyone eats together. I was asked to join and had three excellent lunches with the 45 employees. I showered twice. Everyone was very nice but the almost total lack of English was frustrating. Even though I had done so many things wrong (gas, oil, Ad Blue), it was difficult to find out what I should be doing. There were many very pretty young women working at the garage, none of them married. It is against the rules to wear a hijab at work.

The problem ended up being the DPF (diesel particulate filter), the “soot filter” in the exhaust pipe. It can become plugged if using cheap diesel (Iraq?), semi-synthetic oil, overfilling the oil, driving at low speeds (in the city so few taxis are diesel) without driving at high speeds at least once a month or even bad Ad Blue. The whole thing ended up costing TL 4,193 or €609.50 to fix but included “regenerating the DPF, a car wash, changing the oil and air filter, doing all the checkups, and changing the gas and the Ad Blue. A new DPF costs in the range of €3500-4000!!!

Gas: Shell V-Power

Oil: Castrol Edge Professional

Ad Blue: only from Shell

With about an hour of light left, I drove west and north from Diyarbakir towards Nemrut Dag. With plans to have salad for dinner, I stopped at a small grocery to buy a few ingredients. I was immediately asked to sit down and have dinner in the store – fried goat, a soup of beans and ? mushrooms, warm bread, sliced radish, a herb (celery tops?) and a drink made from beets and hot peppers that was vermillion in colour. Also here were his enormous wife and more enormous mother and two friends, but only the two of us ate.

Then another problem arose as I had no power in my cigarette lighter and the socket I use for my inverter to power my computer. An accessory socket is in the back and thankfully worked and the USB in my glove box provides power to the phone – otherwise I would be screwed.

Nemrut Dağ was a long way out of the way and at the top of the mountain. Snow about 12cm deep stopped me about 8kms from the site. Mid-December may not be the best time to visit here. I was quite disappointed as it looks amazing.

I include this for information’s sake.

NEMRUT DAG

Crowning one of the highest peaks of the Eastern Taurus mountain range in south-east Turkey, Nemrut Dağ is the Hierotheseion (temple-tomb and house of the gods) built by the late Hellenistic King Antiochos I of Commagene (69-34 B.C.) as a monument to himself. Commagene was a kingdom founded north of Syria and the Euphrates after the breakup of Alexander’s empire. Nemrut Dağ is one of the most ambitious constructions of the Hellenistic period. The syncretism of its pantheon (the assimilation of Zeus with Oromasdes, the Iranian god Ahuramazda, and Heracles with Artagnes, the Iranian god Verathragna) and the lineage of its kings can be traced back through two sets of legends, Greek and Persian, both evidence of the dual origin of this kingdom’s culture.

Antiochos I is represented in this monument as a descendant of Darius by his father Mithridates, and a descendant of Alexander by his mother Laodice. This semi-legendary ancestry translates the ambition of a dynasty that sought to remain independent of the powers of both the East and the West. It has an intimate mixture of Greek, Persian and Anatolian aesthetics in the statuary and the bas-reliefs.

With a diameter of 145 m, the 50 m high funerary mound of stone chips is surrounded on three sides by terraces to the east, west and north. Two separate antique processional routes radiate from the east and west terraces. These original ceremonial routes to the Hierotheseion are known and still used for access today.

Five giant seated limestone statues, identified by their inscriptions as deities, face outwards from the tumulus on the upper level of the east and west terraces. These are flanked by a pair of guardian animal statues, a lion and an eagle. The heads of the statues have fallen off to the lower level and also have two rows of sandstone stelae, mounted on pedestals with an altar in front of each stele. One row carries relief sculptures of Antiochos’ paternal Persian ancestors, the other of his maternal Macedonian ancestors. Inscriptions on the backs of the stelae record the genealogical links. A square altar platform is located at the east side of the east terrace.

On the west terrace, there is an additional row of stelae representing the particular significance of Nemrut including the handshake scenes showing Antiochos shaking hands with a deity and the stele with a lion horoscope, believed to be indicating the construction date of the cult area.

The north terrace is long, narrow and rectangular, and hosts a series of sandstone pedestals. The stelae lying near the pedestals on the north terrace have no reliefs or inscriptions.

The Hierotheseion of Antiochos I is one of the most ambitious constructions of the Hellenistic period. Its complex design and colossal scale (some of the stone blocks used weigh up to nine tons) combined to create a project unequalled in the ancient world. A highly developed technology was used to build the colossal statues and orthostats (stelae), the equal of which has not been found anywhere else for this period.

The greatest threat to the integrity of the property is the material damage caused by environmental conditions such as serious seasonal and daily temperature variations, freezing and thawing cycles, wind, snow accumulation, and sun exposure. The height of the tumulus is now reduced from its estimated original 60 m due to weathering, previous uncontrolled research investigations and climbing by visitors. Furthermore, the Nemrut property is located within a first-degree earthquake zone very close to the East Anatolian Fault, which is seismically active.

It has survived in a moderately well-preserved state. A Natural Park was declared in 1988.

Cendere (Severan) Bridge, Kahta. Now a pedestrian bridge, this bridge was built over the Cendere (Cabinas) River by the XVIth legion during the period of Roman emperor Septimus Severus (r. 193-211 AD). One of the best examples of ancient Roman architecture, it is 120m long, 7m wide including the wide sides, and 30m above the river that flows through its single large arch. It had four 8-segment columns on a great base and still with their capitals, each erected for Emperor Severus, his wife J. Domna, and their sons Caracalla and Geta. But Geta was killed and the column erected for him was removed by order of Emperor Caracalla (r. 211-217 AD). The road bed and several segments of the 1½m, eight-stepped sides with benches have been replaced. The river flows through a great gorge just upstream.

It was an 11km drive north of the main highway, but well worth the drive.

ADIYAMAN (pop 242,000)

Adiyaman Museum. The usual ethnography and archaeology, none very interesting. Free

GÖBEKLI TEPE

Predating Stonehenge by 6,000 years, Turkey’s stunning Gobekli Tepe upends the conventional view of the rise of civilization. Now seen as early evidence of prehistoric worship, the hilltop site, when first examined in the 1960s, was shunned by researchers as nothing more than a medieval cemetery, but is now thought to be the world’s oldest temple, the first human-built holy place.

Six miles from Urfa, this ancient city has some of the most startling archaeological discoveries of our time: massive carved stones about 11,000 years old, crafted and arranged by prehistoric people who had not yet developed metal tools or even pottery. The first megaliths found were very close to the surface and scarred by plows. As the archaeologists dug deeper, they unearthed pillars arranged in circles. And because those artifacts closely resemble others from nearby sites previously carbon-dated to about 9000 B.C., it is estimated that Gobekli Tepe’s stone structures are the same age.

The main excavation site consists of a rectangular pit with standing stones or pillars arranged in circles, one of them 65 feet across. Beyond, on the hillside, are four other rings of partially excavated pillars. Each ring has a roughly similar layout: in the center are two large stone T-shaped pillars encircled by slightly smaller stones facing inward. The tallest pillars tower 16 feet and weigh between seven and ten tons. Some are blank, while others are elaborately carved: foxes, lions, scorpions and vultures abound, twisting and crawling on the pillars’ broadsides.

Gobekli Tepe sits at the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent—an arc of mild climate and arable land from the Persian Gulf to present-day Lebanon, Israel, Jordan and Egypt—and would have attracted hunter-gatherers from Africa and the Levant. From this perch 1,000 feet above the valley, the landscape 11,000 years ago, before centuries of intensive farming and settlement turned it into the nearly featureless brown expanse it is today, had herds of gazelle and other wild animals, gently flowing rivers, which attracted migrating geese and ducks; fruit and nut trees; and rippling fields of wild barley and wild wheat varieties such as emmer and einkorn – it was like a paradise.

There is no evidence that people permanently resided on the summit of Gobekli Tepe – no cooking hearths, houses or trash pits, and none of the clay fertility figurines that litter nearby sites of about the same age. Tools including stone hammers and blades have been found and it is believed to be a place of worship on an unprecedented scale—humanity’s first “cathedral on a hill.”

Using ground-penetrating radar and geomagnetic surveys, at least 16 other megalith rings remain buried across 22 acres. The one-acre excavation covers less than 5 percent of the site. Archaeologists could dig here for another 50 years and barely scratch the surface.

Unlike the stark plateaus nearby, Gobekli Tepe (the name means “belly hill” in Turkish) has a gently rounded top that rises 50 feet above the surrounding landscape and thought to be created by man, a gigantic Stone Age site.

Gobekli Tepe’s sloping, rocky ground was a stonecutter’s dream. Even without metal chisels or hammers, prehistoric masons wielding flint tools could have chipped away at softer limestone outcrops, shaping them into pillars on the spot before carrying them a few hundred yards to the summit and lifting them upright. Then, once the stone rings were finished, the ancient builders covered them over with dirt. Eventually, they placed another ring nearby or on top of the old one. Over centuries, these layers created the hilltop.

More than 100,000 bone fragments including tens of thousands of gazelle bones (60 percent of the total), plus those of other wild game such as boar, sheep, red deer and a dozen different bird species, including vultures, cranes, ducks and geese obviously a hunter-gatherer site. The people who lived here had not yet domesticated animals or farmed. The surprising lack of evidence that people lived right there argues against its use as a settlement or even a place where, for instance, clan leaders gathered. Gobekli Tepe’s pillar carvings are dominated not by edible prey like deer and cattle but by menacing creatures such as lions, spiders, snakes and scorpions, a scary, fantastic world of nasty-looking beasts – perhaps these hunters were trying to master their fears by building this complex, which is a good distance from where they lived.

Gobekli Tepe’s builders were on the verge of a major change in how they lived, thanks to an environment that held the raw materials for farming. They had wild sheep, wild grains that could be domesticated—and the people with the potential to do it. Within 1,000 years of Gobekli Tepe’s construction, settlers had corralled sheep, cattle and pigs. At a prehistoric village just 20 miles away, geneticists found evidence of the world’s oldest domesticated strains of wheat; radiocarbon dating indicates agriculture developed there around 10,500 years ago, or just five centuries after Gobekli Tepe’s construction.

These new findings suggest a novel theory of civilization. Scholars have long believed that only after people learned to farm and live in settled communities did they have the time, organization and resources to construct temples and support complicated social structures. Possibly it was the other way around: the extensive, coordinated effort to build the monoliths laid the groundwork for complex societies. The monuments could not have been built by ragged bands of hunter-gatherers. To carve, erect and bury rings of seven-ton stone pillars would have required hundreds of workers, all to be fed and housed. Hence the eventual emergence of settled communities in the area around 10,000 years ago. This shows sociocultural changes come first, and agriculture comes later, a good case this area is the real origin of complex Neolithic societies,

6,000 years before the invention of writing here, there’s more time between Gobekli Tepe and the Sumerian clay tablets [etched in 3300 B.C.] than from Sumer to today. Still, archaeologists have their theories—evidence, perhaps, of the irresistible human urge to explain the unexplainable.

The vulture carvings may have special significance. Some cultures have long believed the high-flying carrion birds transported the flesh of the dead up to the heavens. Possibly beneath the floors will be found the structures’ true purpose: a final resting place for a society of hunters. Perhaps the site was a burial ground or the center of a death cult, the dead laid out on the hillside among the stylized gods and spirits of the afterlife. If so, Gobekli Tepe’s location was no accident. From here the dead are looking out at the ideal view looking out over a hunter’s dream.

Park at the bottom. Tickets are TL 36 to see just the site, and TL 42 to see the animation, whatever that is. Includes a shuttle bus that takes you to the archaeological site 1.2 km away. The only thing of interest is the large covered excavation pit with four “buildings”. A, B (12m across, C, and D.

SANLIURFA

Harran and Sanliurfa Tentative WHS (25/02/2000).

Sanliurfa known as the city of prophets has a very rich and ancient background, due to its location in the great fertile plain of upper Mesopotamia. Sanliurfa was praised as the city of prophets Hiob, Jethro and St. George besides Abraham who was said to have lived here. This Holy city is full of historic religious, public, and civil architectural buildings. All are the best examples of tradition and art stone. The old city of Harran is situated in a land through which have run trade routes from Iskenderun to Antakya (ancient Antioch) and to Kargam~s. The city is mentioned in the Holy bible and in the documents found at Mari (a city in Northern Syria) It is important not only for hosting the early civilizations but it is the place where the first Islamic University is founded. The traditional civil architecture, mud brick houses with conic roofs, are unique.

Urfa bazaar. This is an unexceptional 3-level shopping centre with access from a plaza.

Sanliurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum. TL 14

Urfa City Museum. Since the opening of the new archaeology museum, this is virtually deserted – a lot of documents, certificates, books, photographs, hand tools, musical instruments, traditional clothes, trades and handicrafts from Urfa. TL5

Şanlıurfa Castle (Urfa Castle). Built in 814, it sits on a mountain in the centre of Sanliurfa. From below it has impressive ramparts and moats carved in stone but there is not much to see inside, just crumbling rock walls. Two high Roman pillars are accessible, but the castle itself has been closed for renovations for some time. It is a very historical place mentioned in the Bible, the palace of the Mandilion, the capital of the Crusaders. Great views of the city.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF ZEUGMA (Zeugma Antik Kenti) A tentative WHS (13/04/2012).

Zeugma is 10 km away from Nizip and 50 km west of Gaziantep. Zeugma, literally “bridge” or “crossing” in ancient Greek, was located at the major ancient crossing on the river Euphrates. Zeugma was twin cities on the opposing banks of the river, but today the name Zeugma is usually understood to refer to the settlement on the west bank, called Seleucia after the founder, while the one on the East bank was called Apamea after his Persian wife Apama.

They were Hellenistic settlements established by commander Seleucus Nicator around 300 BCE. The twin settlements were crucial in the cultural policies of the Seleucid Empire integrating Greco-Macedon and Semitic cultures in the region. In 64 CE, Seleucia came under the rule of the Commagene Kingdom, and then from 72 CE, it was the major eastern frontier city of the Roman Empire. With two Roman legions based in Zeugma in the first century CE, the strategic importance and cosmopolitan nature of the city increased greatly. Due to its crucial position on commercial routes and to the volume of its traffic, Zeugma was chosen by the Romans for toll collecting. Zeugma prospered and functioned as a major commercial city as well as a military base.

The preserved parts of the ancient city include the Hellenistic Agora, the Roman Agora, two sanctuaries, the stadium, the theatre, two bathhouses, the Roman legionary base, administrative structures of the Roman legion, the majority of the residential quarters, Hellenistic and Roman city walls, and the East, South and West necropolis (none of this is visible today – only the Roman houses below are visitable).

Most of these remains date from the period between the first century BCE (the time of Antiochus, king of Commagene (64 BCE-72 CE) and the third century CE Roman period when the city was sacked by the Sassanian King Shapur in 253 CE. Commagene was a Roman client kingdom. Commagene is represented by two sanctuaries consecrated by Antiochus in the city showing the key role in Antiochus’ efforts to link the Greek and Persian cultures, under the kingdom’s key position between these two worlds, on the Euphrates. Belkıs Hill – the foremost sanctuary has three colossal cult statues and many others in pieces on the slopes of the hill. They are dexiosis stelai showing Antiochus in a hand-shaking position with the Gods. These statues most probably belong to the deities of the Commagenian pantheon. Both are in the Ganzintep Mosaic Museum.

Necropolis of Zeugma. Tombs and burials from the late 3rd century to the 3rd century AD range from Hellenistic rock-cut cist graves of the earliest Graeco-Macedonian settlers to the late Hellenistic and early Imperial tumuli (rock-cut rectangular slots, loculi-type graves, and rock-cut arched grave niches. The walls of the chambers were covered with frescoes and painted with flowers using bright colours such as red, green, and yellow. Most belonged to elite families in the city.

The Roman Houses of Zeugma form the main covered exhibit. They are in the style of city villas with courtyards, covering around 600-800 square meters each. What makes the houses especially important is that after being demolished during the devastating Sasanian sack of the city in 253 CE, they were mostly uninhabited and kept intact providing invaluable information on daily life in a major Roman frontier city in the mid-third century. What remains are ruins of some walls and about 8 standing columns with mosaics displayed.

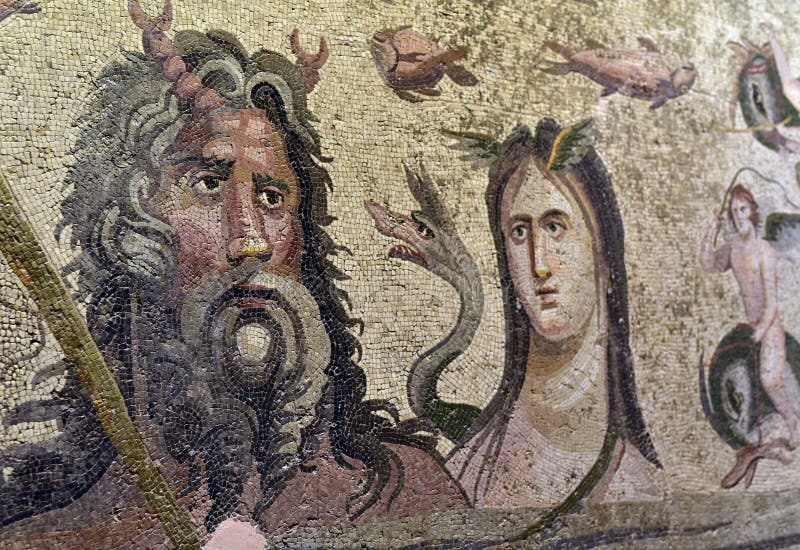

The architectural decoration of the houses mainly consists of exquisite mosaics and frescoes dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. Zeugma mosaics are a unique collection of pictorial art including unique pictorial renderings of Greek and Greco-Roman mythologies and popular novels, some with captions in Greek. Some also bear signatures of mosaicists as well as names of patrons who commissioned the implementation of the mosaics.

The House of Dionysos depicted the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne, complete with servants bringing wedding presents and musicians. The House of Danae has a mosaic depicting the moment when Danae and Perseus were rescued by the fishermen Dictys on the shores of Seriphos Island after having drifted ashore in a nuptial chest. This house has some faded frescoes in one room. Most of the rest of the mosaics are some nice geometrics.

The Houses of Poseidon and Euphrates are lower and flooded by the dam on the Euphrates River built in 2000. Most of the mosaics and frescoes found in them were relocated to the Gaziantep Museum.

This sits on the banks of the Euphrates Reservoir about 7 km north of the highway. Park at the grossly overbuilt Visitors Center and walk 400m to the exhibit. Free

GAZIANTEP (pop 1,675,000)

Zeugma Mosaic Museum. With 66 mosaics, most from Zeugma, this is not to be missed. The Theonoe Mosaic at 71.57m2, is the largest and was rescued from the bottom of the reservoir (Birecik Dam) only when the water level dropped in 2002. Many are geometrics and Greek and Roman mythological scenes with an variety of geometric borders. A separate building houses several Byzantine 5th century mosaics including a huge one from a church. These are not as well done as the Zeugma mosaics.

.jpg)

There are also sarcophagi, frescoes from Zeugma, and all the stelae from Zeugma. TL24

Gaziantep Castle. Sitting on a hill in the middle of Ganziantep, it was built by the Hittites as an observation point and later built into the main Roman castle in the 2nd-3rd centuries. It was renovated to its present state by the Byzantines under Justinian in 527-565. It was the main site of defence of Gaziantep against French troops attempting to invade after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The museum inside relates to the Turkish War of Independence.

Omeriye Mosque. Although the exact construction date is unknown, the first written record is from 1210, so was possibly built around 1150. Omereyn means “Two Omers”. It took its present shape in 1786 and was restored in 1850 and 2006. The main entrance door and mihrab are black and white stone and red marble. Inside, it is rough yellow stone, small with 3 arches and two black columns. Black, white and pink stones form the floor of the courtyard. The minaret has bullet marks from the War of Independence.

Coppersmith’s Bazaar (Bakirclar Carsisi). This atmospheric market has a little bit of everything but maybe the metalwork dominates. Several shops were pounding copper, most making decorative plates and plaques. The spice and coffee sections have great smells.

UNDERGROUND WATER STRUCTURES in GAZIANTEP: Livas and Kastels. Tentative WHS:

Dating to the 5th century, Gaziantep is located on the edge of the Alleben Stream and forms a C shape. The stream has low water levels further reduced by high summer temperatures with high evaporation. Geologically, lakes don’t form as most rainfall seeps underground. For all these reasons, the settlement has required water transport.

Livas are the underground water tunnels – well-calculated and gently sloping tunnels – excavated by human labour in the soft limestone, clayey limestone, and chalk formation that the city is situated on. Water is brought from the main source far from the city and distributed to the required places. New tunnels were added as the city grew creating a cobweb of livas continuing for miles.

The oldest livas line carrying water to the old city center is the Pancarlı Livas Line bringing water to the city from about 14 km northwest. The period of construction is uncertain. In the Ottoman era this line provided water for many monumental structures in the city, such as khans, madrasahs, baths, mosques, fountains and private houses by way of wells.

Kastels are the water structures that open the water coming from these tunnels for public use. Depending on the elevation of livas, kastels are located at varying depths. Instead of adding a system to bring up the water, they were built at the water level. Some are completely below ground while some are partly below ground. Kastels are comprehensively planned to serve the toilet, laundry, and clean water needs of the people. They perform different functions such as pools, wells, sitting places, small mosques, showers, toilets, and bathing places. They became an important meeting place in daily social life and were also used to cool off during hot summer days. They are both architecturally and culturally unique structures

A livas system provides clean water for every Kastel structure while the sewage is moved from the structures by another system. Livas have similar construction technology to underground water channels known as qanât seen in many parts of the world.

The right to use water and make a connection to the main livas was subject to permission. Every user on the line had to keep the water clean and was governed by social rules in the society creating a social interdependence and responsibility, based on water, which reflects social norms. The system of livas’ and water structures.

Digging of livas entails important engineering knowledge – the right slope at every point to provide a constant flow for hundreds of kilometres in the right direction. Maintenance and repair work had to be done. Those who work in the maintenance and repair of the livas’ are called ‘kanavatcı’ in the local language.

Six kastels have survived of which I saw the first three.

Kastel of İhsan Bey (Esenbek). Dating to the 15th century, it is completely below- ground located under the courtyard of the mosque (remarkably similar to the Omeriye Mosque), both rock-carved places and with masonry walls. It includes a pool, places to sit a small mosque, and a museum. The entrance is next to the minaret but was not open.

The water for here comes from Dutluk even though they are all within a block or so of each other.

The only way to enter is via the museum. Follow the maze of corridors to find your way down through the caverns. There is running water into a shallow square pool surrounded by stone benches, a narrow shallow tunnel (that didn’t look like it should be entered, an elevated prayer bench, and more benches.

Kastel of Şeyh Fethullah. In the courtyard of Şeyh Fethullah Mosque with a hamam, madrasa, and zawiyah. Half of the kastel is above ground with two pools (only one with water but with a star design in the pool) and WC spaces.

Kastel of Pişirici (Beşinci). Constructed during the period of Mameluke, in1282-83, it is the oldest of the existing kastels in Gaziantep and it has the most developed plan scheme, with two connected spaces. Going down the stairs from ground level, the first space encountered houses pools, places to sit, WC and a bathing pool, while the second space functioned as a small mosque. It is open to the public.

There is a lot of water flowing here through many channels in niches around the pools. The water here (and for Seyh, comes from Parcarli, 14kms to the northwest).

Kastel of Kozluca. Located south of the Kozluca Mosque, half of the kastel is above ground with a traditional dwelling constructed over and serves as a museum today.

Kastel of Ahmet Çelebi. A simple kastel, it includes only a pool and a well and is now used as a part of Ahmet Çelebi Mosque.

Kastel of İmam Gazali. Completely below- ground it is a simple plan with rock-carved stairs to a rock-carved pool. This place is used for worship.

Water structures are important documents of human history because they describe the architectural, engineering, technological information, and social and cultural life of the society to which they belong. The Livas’ and kastel system is an exceptional example in terms of the transformation of the management of public water resources into a cultural tradition.

Unconscious interventions in the city center resulting from the construction activities after the 1950s have led to livas’ being interrupted in places. It is required to document the livas before any kind of construction intervention is made in the urban conservation area. It is planned to completely remove the basement floor permit for construction activities.

Livas’ and kastels used for at least 800 years were used by the Gaziantep people until the 1950s. The livas’ between the Pişirici, Kozluca, İhsan Bey, and Fethullah Kastels have been cleaned by the municipality to restore their original function.

Whether called ‘qanât’ or ‘karez’, this system has developed from the first millennium B.C. to today and can be seen in an area from China to Iran, Yemen, and even Mexico.

Water management through qanât systems played a crucial role in the development of the Silk Road. – the Persian Qanat in Iran, Bam, Karez in Pakistan, and Karez Wells in China are all on the Tentative List.

Other underground water tunnels are mainly aimed at irrigating agricultural land, while they contribute to urban use in some places. The livas’ of Gaziantep, unlike these structures, were excavated mainly to bring clean water to the people of the city and not for agricultural irrigation. The kastel structures in Gaziantep are dated mostly to the Ottoman period, while the livas’ are estimated to be earlier.

Gaziantep Planetarium and Science Center. This is an attractive building with a slanted glass roof with a gold round globe in the middle of the roof. Enter the planetarium on the 3rd floor. The people here were lovely. I saw “Black Holes”, a 22-minute movie for free (They didn’t look like they had many visitors and treated me as their guest).

Gaziantep Zoo. In a lovely park of pine trees, this “safari” park has mostly African animals. TL7

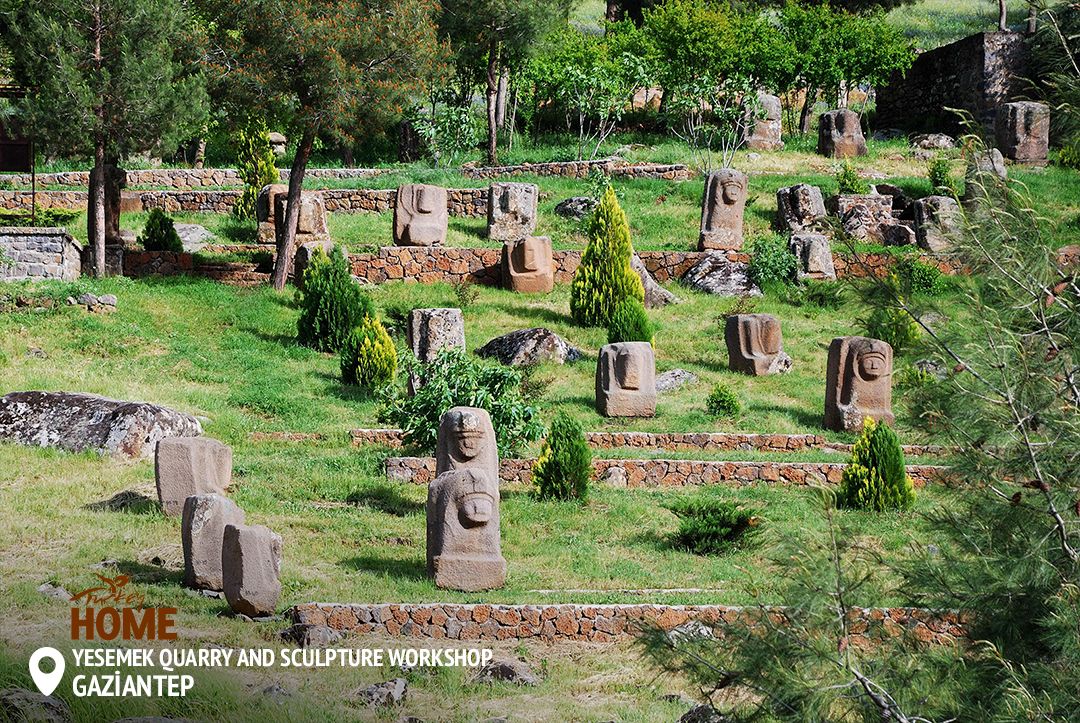

YESEMEK QUARRY AND SCULPTURE WORKSHOP (13/04/2012)

Located 23 km Southeast of Karatepe and 113 km from Gaziantep. The Workshop covers an approximate area of 400×20 meters beginning from the watercourse of Yesemek Brook rising upwards about 90 meters.

Composed of high-quality and thin porous volcanic dolerite/basalt rocks, the area was used as a quarry and a workshop dating to 900-800 B.C. as a center of mass production of sculptures manufactured for the capital of the Samal Kingdom. Following the collapse of the Kingdom against the Assyrians during the 8th century B.C., the quarry and workshop were closed and the workers left the region. The surface was covered with soil and was frozen in the 8th century B.C.

It was the biggest open-air sculpture workshop of Antique Front Asia, providing information about the process from a stone block to a sculpture. More than 300 hundred sculptures and orthostats from the Late Hittite Kingdom show the development of art and technology in sculpture production. First, the size of the block that would be cut from the quarry was determined and deep grooves were opened around it to put trees inside. The required part was cut from the rock by breaking the rock through the pressure caused by the expansion of trees after watering. These rough rectangular prism-shaped blocks weighing 500kg up to 15 tons were then sculptured on the hill by the sculpture craftsmen to a certain level and then transferred to neighbouring cities to complete the details of the sculpture according to the demands of the people who ordered them. Hundreds of lions and sphinx figures, many god reliefs and more than 300 sculptures and orthostats with reliefs in different manufacturing stages are undamaged. The sculptures at Yesemek are not only artworks but also represent the religious beliefs of their age.

Certain sculpture workshops similar to the one at Yesemek can be observed over different periods throughout the Ancient Near East: Boğazköy and Kalınkaya (near Alaca Höyük) in Anatolia, Domuztepe and Carchemish in Southeastern Anatolia, Sikizlar (Sekizler) in Syria, Minet el Beida and Tiripoli in Syria and Aswan in Egypt. The sculptures produced in these workshops are generally of a higher artistic standard than the sculpture blocks in Yesemek.