TEMPLE GRANDIN (1947 – ).

In 1989, she spoke at a conference of autism professionals and educators about “high-functioning individuals with autism”. “I am a 44-year-old autistic woman who has a successful international career designing livestock equipment. I completed my Ph.D. in Animal Science at the University of Illinois in Urbana and I am now an Assistant Professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University.” Few people had seen a mature woman who called herself autistic. This conference effectively launched Grandin’s career as a public speaker. Two decades later, the scene was created for the Emmy-winning biopic Temple Grandin, starring Clare Danes.

Recounting the story of her life in her inimitably gruff and blunt-spoken way, Grandin cast more light on the day-to-day reality of autism than decades of clinical observation and speculation had managed to produce. She was unable to speak until age three but was fortunate to get early speech therapy. Her teachers also taught her how to wait and take turns when playing board games. She was mainstreamed into a normal kindergarten at age five but struggled with severe behavioural issues through her teens as she was considered weird and teased and bullied in high school. The only places she had friends were activities where there was a shared interest such as horses, electronics, or model rockets. She had managed to avoid institutionalization only because the neurologist who initially examined her diagnosed her with brain damage rather than autism. When she was young, Mr. Carlock, her science teacher, was an important mentor who encouraged her interest in science. When she had a new goal of becoming a scientist, she had a reason for studying. She believes labels like high-functioning and low-functioning were too simplistic. Today half the cattle in the United States are handled in facilities she has designed.

Grandin characterized descriptions of nonverbal children as willfully oblivious to the people around them as terribly misguided. “If adults spoke directly to me, I could understand everything they said, but I could not get my words out.” My mother and teachers wondered why I screamed. Screaming was the only way I could communicate.”

She pointed out the inadequacy of existing empirical methods for capturing the sensory sensitivities at the core of the autistic experience. There was nothing unusual with her hearing. She described being bombarded with certain sounds as like “having a hearing aid stuck on “super loud”. The reason she misbehaved in church so often as a little girl was the unfamiliar petticoats, skirts, and stockings she was forced to wear on Sundays felt scratchy against her skin.

She pointedly referred to her autism as a “handicap” rather than a mental illness, invoking the humanizing language of disability over the stigmatizing lexicon of psychiatry.

She described the ways the visual nature of her thought processes and memory had given her practical advantages in her career. “If someone says the word cat, my images are of individualized cats I have known or read about. I do not think of a generalized cat. My career as a designer of livestock facilities maximizes my talent areas and minimizes my deficits. . . . Visual thinking is an asset for an equipment designer. I am able to ‘see’ how all the parts of a project fit together and see potential problems.”

Then she traced the roots of her creative gifts through the branches of her family tree, describing her paternal great-grandfather as a maverick who launched the biggest corporate wheat farm in the world and her maternal grandfather as a shy engineer who helped invent the automatic pilot for airplanes. All three of her siblings think visually and one of her sisters, a gifted interior designer, is dyslexic.

Her emphasis on the virtues of atypical minds marked a significant departure from the view of most psychologists, who framed the areas of strength in their patients’ cognitive profiles as mere “splinter skills” – islands of conserved ability in seas of general incompetence. Instead, Grandin proposed that people with autism, dyslexia, and other cognitive differences could make contributions to society that so-called normal people are incapable of making.

Grandin pays tribute to her mentors, starting with her mother, Eustacia Cutler, who never lost faith in her potential and fought many battles to ensure that Temple got an education. William Carlock was the high school science teacher who channelled her teenage fascination with cows into a career in animal science. The turning point in her life occurred one summer at her Aunt Ann’s ranch when she noticed that fearful calves calmed down when herded into a device called a squeeze chute that held them securely in place. When it also alleviated her “nerve attacks”, she devised a similar apparatus for herself. It also made her more emotionally connected to the people around her. “For the first time in my life, I felt a purpose for learning.”

As one of the first adults to publicly identify as autistic, Grandin helped break down decades of shame and stigma. To most clinicians at the time, the notion of an autistic adult with a doctorate and a successful career seemed implausible at best. In 1986, she wrote her memoir Emergence the first book written by a recovered autistic individual.

Dr. Grandin did not talk until she was three and a half years old. Oliver Sacks wrote in the forward of Thinking in Pictures that her first book Emergence: Labeled Autistic was “unprecedented because there had never before been an inside narrative of autism.” Dr. Oliver Sacks profiled Dr. Grandin in his best-selling book Anthropologist on Mars.

It soon became obvious to her that she had not recovered but had learned, with great effort, to adapt to the social norms of the people around her. “When I said that early stuff, I didn’t realize how different my thinking was. I was doing a lot of construction projects in the early ’90s, and I could draw something and test run that piece of equipment in my mind. I could draw the layout for a meat-cutting line and could make the conveyors move.” She began to think of herself as having a powerful digital workstation in her head, capable of running instantaneous searches through a massive library of stored images and generating 3-D videos from the sketches on her drafting table.

She noticed how many parents at autistic conferences were gifted in technical fields. “I started to think of autistic traits as being on a continuum. The more traits you had on both sides, the more you concentrated the genetics. Having a little bit of the traits gave you an advantage, but if you had too much, you ended up with very severe autism.” She warned that efforts to eradicate autism from the gene pool could put humankind’s future at risk by purging the same qualities that had advanced culture, science, and technological innovation for millennia.

Adults with autism and their parents are often angry about autism. Why would nature or God create such horrible conditions? However, if the genes that caused these conditions were eliminated, there might be a terrible price to pay. Persons with bits of these traits are more creative, or possibly even geniuses. If science eliminated these genes, maybe the whole world would be taken over by accountants.

Dr. Grandin became a prominent author and speaker on both autism and animal behaviour. Today she is a professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University. She also has a successful career consulting on both livestock handling equipment design and animal welfare. She has been featured on NPR (National Public Radio) and a BBC Special –”The Woman Who Thinks Like a Cow”. She has also appeared on National TV shows such as Larry King Live, 20/20, Sixty Minutes, Fox, and Friends, and she has a 2010 TED talk. Articles about Dr. Grandin have appeared in Time Magazine, New York Times, Discover Magazine, Forbes, and USA Today. HBO made an Emmy Award-winning movie about her life and she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2016.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association revised the diagnostic criteria for autism. This greatly broadened the spectrum. It now ranges from brilliant scientists, artists, and musicians to an individual who cannot dress themselves. Over the years, the diagnostic criteria have kept changing. It is not precise like a lab test for strep throat. Labels such as autism, ADHD, sensory processing disorder, or learning disability are often applied to the same child. In older children with no speech delay, the diagnosis sometimes switches back and forth between autism and ADHD.

“One of the problems today is for a kid to get any special services in school, they have to have a label. The problem with autism is you’ve got a spectrum that ranges from Einstein to someone with no language and intellectual disability,” said Grandin. “Steve Jobs was probably mildly on the autistic spectrum. Basically, you’ve probably known people who were geeky and socially awkward but very smart. When do geeks and nerds become autistic? That’s a gray area. Half the people in Silicon Valley probably have autism.”

As the number of children diagnosed with autism continues to rise nationally, Grandin is sharing her message about the disorder and “differently-abled brains” with packed houses. At the heart of that message is this: “Rigid academic and social expectations could wind up stifling a mind that, while it might struggle to conjugate a verb, could one day take us to distant stars.”

“Parents get so worried about the deficits that they don’t build up the strengths, but those skills could turn into a job,” said Grandin, who addresses scientific advances in understanding autism in her newest book, “The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum.” These kids often have uneven skills. We need to be a lot more flexible about things. Don’t hold these math geniuses back. You’re going to have to give them special ed in reading because that tends to be the pattern, but let them go ahead in math.”

Early diagnosis can lead to early intervention and access to special education programs, and, while crucial for children with speech delay, also means a permanent label that ultimately could impede progress and the healthy development of a child’s identity. There are other situations where an autism diagnosis is helpful for an older person who is having problems with relationships. It can give them great insight, and enable them to improve relationships.

A label can also impact parental expectations, a major source of therapeutic momentum for children. A parent with a diagnosed autistic child might be reluctant to teach practical social skills that are outside the child’s comfort zone, such as ordering food at a lunch counter. You have to stretch these kids just outside their comfort zone to help them develop. Give them choices of “stretching” activities such as you can do Boy Scouts or robotics.

“It hurts because they don’t have enough expectations for the kids. I see too many kids who are smart and did well in school, but they’re not getting a job because when they were young, they didn’t learn any work skills,” Grandin said. “They’ve got no life skills. The parents think, ‘Oh, poor Tommy. He has autism so he doesn’t have to learn things like shopping.” Grandin was raised by her mother in the 1950s, a time when social skills were “pounded into every single child,” she said. “Children in my generation, when they were teenagers, had jobs and learned how to work. I cleaned horse stalls. When I was 8 years old, my mother made me be a party hostess – shake hands, take coats, etc. In the 1950s, social skills were taught in a much more rigid way so kids who were mildly autistic were forced to learn them. It hurts the autistic much more than it does the normal kids to not have these skills formally taught.”

“In my generation, paper routes taught important working skills. Today, parents should set up jobs a child can do in the neighborhood such as walking dogs for the neighbors. Younger children can do volunteer jobs outside the home such as being an usher at a house of worship or community center. This will teach both discipline and responsibility. It improved my self-esteem to be recognized for doing a job well.” “The skills that people with autism bring to the table should be nurtured for their benefit and society’s,” Grandin said. “

And, if a cure for autism were found, she would choose to stay just the way she is. “I like the really logical way that I think. I’m totally logical. In fact, it kind of blows my mind how irrational human beings are,” She said. “If you totally get rid of autism, you’d have nobody to fix your computer in the future.”

If algebra had been a required course for college graduation in 1967, there would be no Temple Grandin. At least, no Temple Grandin as the world knows her today – professor, inventor, best-selling author, and rock star in the seemingly divergent fields of animal science and autism education. “I probably would have been a handyman, fixing toilets at some apartment building somewhere,” said Grandin. “I can’t do algebra. It makes no sense. Why does algebra have to be the gateway to all other mathematics?”

The abstract concepts in algebra present a common stumbling block for many with an autism spectrum disorder, dyslexia, or other learning problems. Many of the kids would do well if geometry was substituted for algebra. For autistic and photo-realistic visual thinkers, such as Grandin, understanding comes from being able to see and work through a concept in images, creating what is in effect, a virtual reality program that plays out in the brain. In this manner, Grandin, who didn’t speak until she was almost 4, conceptualized down to minute details her design for a humane livestock restraint system now used on nearly half of the cattle in the U.S.

Fortunately, the academic trend in the late 1960s was finite math, a course Grandin passed with the help of tutors and devoted study, satisfying her college math requirement. She went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in psychology and both master’s and doctoral degrees in animal science. For the past two decades, she’s been a professor at Colorado State University.

In her book, The Autistic Brain, she presents research findings that definitely show three types of specialized thinking. They are the photorealistic visual thinkers who think the way I do, math/pattern thinkers, and word thinkers. Children who think differently will often thrive if they have more hands-on activities. Parents need to work with the schools to make sure that elementary school children have art, music, theatre, sewing, woodworking, computer programs, and cooking. These classes teach important career skills and provide opportunities for students to have social interactions with their peers. Older students need to have access to career-related classes such as welding, auto mechanics, and computer science.

There is a huge shortage of skilled mechanics. When I worked in construction installing my systems, I worked with many talented mechanics and metal fabricators. Some of them may have been on the milder end of the autism spectrum. These people were brilliant and they built very complicated things. Skilled trades are not for everybody on the spectrum. I estimate that a skilled trade would be a good choice for 25% of fully verbal people with ASD. When I look back on my long career, some of the best days of my life were out at a construction site. It was so much fun to talk about building things.

– 1 in 59 U.S. children has been identified with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

– ASD is 4.5 times more common in boys (1 in 42) and in girls (1 in 189).

– About 1 in 6 children in the U.S. had a developmental disability from 2006-2008.

Oliver Sachs visited Grandin at Colorado State University. His own views of autism were swiftly evolving, informed by the insights of Lorna Wing, Uta Frith, and the others in the London group. He suspected that in writing Emergence, Grandin’s co-author, Margaret Scariano, must have ghostwritten it. “The autistic mind, it was supposed at the time, was incapable of self-understanding and understanding others and therefore of introspection and retrospection. How could an autistic person write an autobiography? It seemed a contradiction in terms.” After reading dozens of her papers, he found that Grandin’s distinctive persona – that of an irrepressibly curious observer of society from the outside, an “anthropologist on Mars,” as she put it – was consistent throughout. She was clearly writing in her own voice.

He eventually realized that autistic people were capable of “getting” humour. Autism must be seen as a whole way of being, a deeply different mode or identity, one that needs to be conscious (and proud) of itself. In an environment designed for their comfort, they don’t feel disabled; they just feel different from their neighbours.

Sachs spent several days with Grandin. Grandin was amused to discover that the eminent neurologist was nearly as eccentric as she was. “He was like a kindly absentminded professor who zoned out a lot.” In his next best-selling book, An Anthropologist on Mars, he wrote an in-depth profile of her that became the centrepiece of the book. After 50 years of describing autistic people as befitting robots or “imbeciles”, Sachs presented Grandin in the full breadth of her humanity – capable of joy, whimsy, tenderness, passion about her work, exuberance, longing, philosophical musing on her legacy, and sly subterfuge. He acknowledged the prevailing theory that autism is “foremost a disorder of affect, of empathy”, but also explored her deep sense of kinship with other disabled people and with animals, whose fates she saw as intertwined in a society that views them both as less than human.

The chances of Grandin’s perspective taking root among autism professionals, however, were slim. The notion that an autism diagnosis was a fate worse than death proved hard to dispel – “a terminal illness . . . a dead soul in a live body.”

The diagnosis inspired the creation of a whole new set of dehumanizing stereotypes in the media. The first mention of Asperger’s syndrome in the English language, in the Toronto Star in 1989, described “strange” and “clumsy” nerds who read books compulsively without understanding them, were incapable of friendship, and burst into tears and laughter for no reason. The second mention, in the Sydney Morning Herald, led off with the sentence, “It is the plague of those unable to feel.”

Even parent advocacy groups ignored autistic adults. Presentations at conferences dwelled on the usual deficits and impairments, rather than on exploring the atypical gifts that Grandin found so useful in her work.

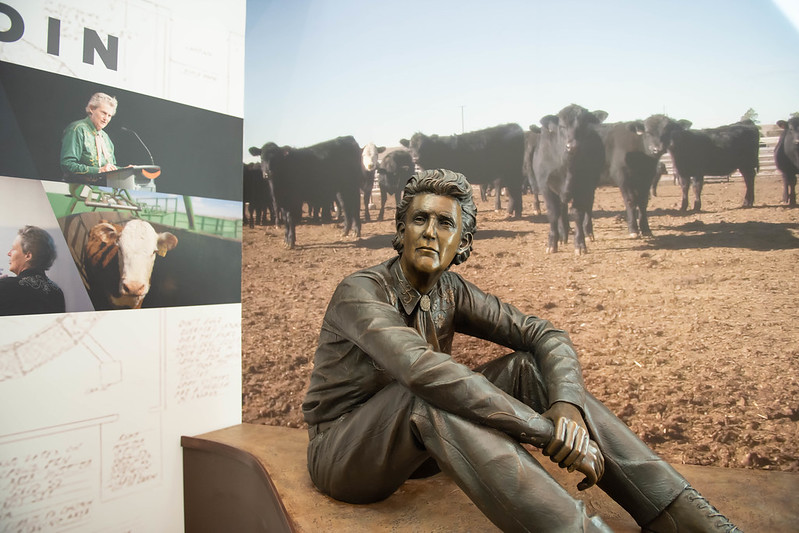

Temple has been honored with a sculpture housed within the JBS Global Food Innovation Center on the Colorado State University Campus.

Personal Life. I think using animals for food is an ethical thing to do, but we’ve got to do it right. We’ve got to give those animals a decent life, and we’ve got to give them a painless death. We owe the animals respect. —Temple Grandin

Grandin says that “the part of other people that has emotional relationships is not part of me”, and she has neither married nor had children. She later stated, for example, that she preferred the science fiction, documentary, and thriller genres of films and television shows to more dramatic or romantic ones. Beyond her work in animal science and welfare and autism rights, her interests include horseback riding, science fiction, movies, and biochemistry.

She has noted in her autobiographical works that autism affects every aspect of her life. Grandin has to wear comfortable clothes to counteract her sensory processing disorder and has structured her lifestyle to avoid sensory overload. She regularly takes antidepressants, but no longer uses her squeeze machine, stating in February 2010: “It broke two years ago, and I never got around to fixing it. I’m into hugging people now.”

OLIVE SACKS (1933-2015)

He was a neurologist who was a precise observer of the world. He met a pair of identical twins named George and Charles Finn who had been variously diagnosed as autistic, schizophrenic, and mentally retarded. “Give me a date!”, they would cry in unison, and they would instantly calculate the day of the week for any date in a multiple-thousand-year span. As they executed these seemingly impossible cognitions, they would focus their attention inward – their eyes darting back and forth behind thick glasses. They would enjoy conversations that consisted solely of numbers. George would utter a string of digits, and Charles would turn them over in his mind and nod; then Charles would reply in a similar fashion, and George would smile approvingly. Sacks was shocked that the twins were instantly calculating six-digit prime numbers, a feat that even a computer would have found difficult to pull off at the time. Consulting a book of prime number tables, he casually dropped an eight-digit prime into the conversation. Surprised and delighted, they had no problem and raised him with even longer primes. Yet George and Charles were incapable of performing simple multiplication, reading, or even tying their own shoes.

Then Sacks met Jose, a 21-year-old autistic man described as an idiot and unable to comprehend language or time. But when asked to draw a watch, he drew every feature of it, not just the time. Jose was fond of the non-human world, especially plants, and he drew flowers with feeling and great accuracy.

Sacks realized that, instead of incommunicative, his patients were communicating all the time – not in words, but in gestures and other nonverbal forms of utterance, particularly among themselves. He also objected to Lovaas’s “therapeutic punishment” used in his studies at UCLA.

When Sachs made the provocative suggestion in 2001 that Henry Cavendish had Asperger’s, it was hard to remember an era when autism wasn’t a frequent topic of conversation, even among people who had no personal connection to the subject. But enormous changes had taken place in an astonishingly short period. Just fifteen years earlier, mothers of autistic children often had to gently correct neighbours who thought they’d said their son or daughter was “artistic.” The few pediatricians, psychiatrists, and teachers who read about the obscure condition in a textbook could safely assume that they would get through their entire careers without having to diagnose a single case.

For decades, estimates of prevalence had remained stable at just four or five per ten thousand. But that number started to snowball in the 1980s and 90s, raising the frightening possibility that a generation of children was in the grips of an epidemic of unknown origin. Books like Clara Claiborne Park’s The Siege, Oliver Sack’s An Anthropologist on Mars, and Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures offered a view of the diverse world of autism from a unique vantage point.

The Siege: Published in 1967, it was the first book-length account of raising an autistic child by a loving and devoted parent. In a dark age when psychiatrists falsely blamed “refrigerator mothers” for causing their children’s autism by providing them with inadequate nurturing.

An Anthropologist from Mars: He described the challenges faced in day-to-day life while bringing the strengths of their atypical minds to their work. “No two people with autism are the same – the precise form of expression is different in every case. There may be a most intricate (and potentially creative) interaction between the autistic traits and other qualities of the individual. While a single glance may suffice for clinical diagnosis if we hope to understand the autistic individual, nothing less than a total biography will do.”

Thinking in Pictures was a biography from the inside. Encouraged by her mother and a supportive high school science teacher, she developed her instinctive kinship with animals into a practical set of skills that enabled her to succeed in the demanding job of designing facilities for the livestock industry. She came to regard her autism as both a disability and a gift, as different, not less.

Sacks himself had played a role in the sea change by making the distinctive traits of autism recognizable to his colleagues in his sensitive portrayals of artist Stephen Wiltshire, the calculating twins, George, and Charles Finn, and industrial designer Temple Grandin in An Anthropologist on Mars and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. He was an advisor to Dustin Hoffman for Rain Man.

Personal Life. Sacks never married and lived alone for most of his life. He declined to share personal details until late in his life. He addressed his homosexuality for the first time in his 2015 autobiography On the Move: A Life. Celibate for about 35 years since his forties, in 2008 he began a friendship with writer and New York Times contributor Bill Hayes. Their friendship slowly evolved into a committed long-term partnership that lasted until Sacks’s death; Hayes wrote about it in the 2017 memoir Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me.

In Lawrence Weschler’s biography And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? he is described by a colleague as “deeply eccentric”. A friend from his days as a medical resident mentions Sacks’ need to cross taboos, like drinking blood mixed with milk, and how he was deeply into drugs like LSD and speed in the early 60s. Sacks himself shared personal information about how he got his first orgasm spontaneously while floating in a swimming pool, and later when he was giving a man a massage. He also admits having “erotic fantasies of all sorts” in a natural history museum he visited often in his youth, many of them about animals, like hippos in the mud.

Sacks noted in a 2001 interview that severe shyness, which he described as “a disease”, had been a lifelong impediment to his personal interactions. He believed his shyness stemmed from his prosopagnosia, popularly known as “face-blindness”, a condition that he studied in some of his patients, including the titular man from his work The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. This neurological disability of his, whose severity and life impacts Sacks did not fully grasp until he reached middle age, even prevented him from recognizing his own reflection in mirrors.

Sacks swam almost daily for most of his life, beginning when his swimming-champion father started him swimming as an infant. He especially became publicly well known for swimming when he lived in the City Island section of the Bronx, as he would routinely swim around the entire island, or swim vast distances away from the island and back.