Xinjiang – September 5-12 and 22-30.

This is China’s far-flung and restive western frontier, at odds with Beijing since time immemorial. But these cultural differences between the two are what make this province so attractive to travellers. Central Asian culture is still very much alive in this Uighur homeland – from delicious kababs to calls to prayer from the neighbourhood mosque. Silk Road sites and awesome landscapes make Chinese Turkestan a trip into the superhighways of the Asian continent. Xinjiang is huge and borders on many countries: Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

History. By the 2nd century BC, the expanding Han dynasty had pushed its borders west into Xinjiang. Military garrisons protected the fledging routes as silk flowed out of China in return for horses needed to fight nomadic incursions into the north. Rule collapsed after the Han and reasserted itself during the 7th-century Tang, but control was tenuous.

A Uighur kingdom based in Khocho thrived from the 8th century transforming the Central Asian people from nomads to farmers and Manichaeans (a dualistic Persian religion that borrowed figures from Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism) to Buddhists. Islam took hold in the 10th to 12th centuries.

In 1219 Yili, Hotan and Kashgar fell to the Mongols and their various successors controlled the whole of Central Asia until the mid-18th century, when the Manchu army took Kashgar. By 1885, it was incorporated into China’s newly created Xinjiang (New Frontier) province.

With the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, Xinjiang came under the chaotic and violent rule of a succession of Muslim and Chinese warlords.

Since 1949, China’s goal has been to keep a lid on ethnic separatism while flooding the region with Han settlers. The Uighurs once composed 90% of Xinjiang’s population; today they make up less than 50%. China developed the region’s oil resources to ramp up the local economy but the increased arrival of Han settlers has only exacerbated ethnic tensions. In 2008, street protests and bomb attacks rocked the province and communal violence in 2009 between Han and Uighur civilians in downtown led to 200 deaths and 1700 injuries. With sporadic violence continuing, the whole province remains under quasi-martial law with thousands of Uighurs arrested and intermittent internet blocking.

Today Uighur and Han communities remain effectively segregated in Xinjiang towns. Economic marginalization, cultural restrictions and ethnic discrimination continue to fuel Uighur resentment and isolated violence continues.

The climate is one of extremes. Turpan is the hottest spot in the country – up to 47°C in the summer. Spring also has frequent sandstorms making travel difficult. Winters see the temperature plummet to below 0°C throughout the province. Late May through June and September through October (especially) are the best times to visit.

Language. Uighur is the traditional lingua franca. It is part of the Turkic language family and is similar to Uzbek, Kazakh and Kyrgyz. The one exception is Tijik, which is related to Persian.

The Han Chinese don’t speak Uighur and many Uighurs can’t or won’t speak Mandarin. Now learning Mandarin is mandatory in Uighur-language schools (but not the other way around), and is exclusively used in universities, nominally to provide more economic opportunities to the Uighurs. But resistance is steadfast, out of concern the Uighur culture and tradition will be diluted. Most business signs and all road signs are in Arabic and Chinese script, but rarely English.

Time. All of China operates on Beijing time, but Xinjiang is a full two time zone west.

Uighur Food.

Pulled noodles and Torn noodle squares – topped with mutton, peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, and garlic shoots.

kababs – mutton, they are a staple usually flavoured with cumin. The liver ones are low-fat.

Nan bread – another staple often sprinkled with poppy seeds, sesame seeds or fennel, a great accompaniment to kababs.

Opke – a broth of bubbling goat’s heads and coiled stuffed intestines. I would avoid this.

Baked mutton dumplings – delicious. Cooked in a vertical oven by sticking them to the inside walls of the oven. The amount of fat is widely variable.

Desserts: vanilla ice cream; fried dough balls filled with sugar, raisins and walnuts; mixed shaved ice with syrup, and yoghurt; walnut nut loaf; a paste of walnuts, raisins, almonds and sugar.

Fruit: apricots, grapes, watermelon, sweet melon, pears and raisins all abundant July to September.

September 2 was the 70th anniversary of the end of the anti-Japanese War and was commemorated with a massive military parade. China suffered more than any other country in WWII with 20 million deaths and 15 million wounded. China feels that the rest of the world does not appreciate China’s losses and role in the war – the “forgotten ally”. Besides these casualties, a particularly awful aspect of the war was the many Chinese and Korean women forced into Japanese brothels – something never acknowledged by Japan.

September 5 also marks the 50th anniversary of the creation of the Tibetan Autonomous Region. It was interesting to watch the CCTV American channel that has had frequent shows documenting how Han Chinese involvement in Tibet has produced huge economic progress. One show profiled a family (all active members of the Communist Party) that has done particularly well.

TURPAN (pop 58,000)

At 154m below sea level (and the second-lowest depression in the world), this is China’s Death Valley and the hottest spot in China. In July and August, temperatures soar to above 40°C, forcing a state of semi-torpor.

The groundwater and fertile soil of the Turpan basin make it a veritable oasis in the desert, with century-old remains of ancient cities, imperial garrisons and Buddhist caves. The town itself is a fairly recent creation and has an extremely mellow vibe.

Entering Xinjiang entailed a whole new level of security. At Liuyuan South train station, I had to drop my pack outside of the train ticket office and was frisked by a woman. Warning: do not bring any knives with you – I had my nice Swiss Army knife confiscated (a good alternative is to tuck it under your belt as they don’t frisk here). It was claimed too dangerous to bring. I imagine the same restrictions apply to arriving in Tibet. Swat teams patrolled the outside and inside of the station. My view out the window was mostly of the cement fence bordering the track. Wind farms were everywhere.

I arrived at Turpan North (high-speed railway station), caught a taxi with a bunch of Chinese guys and found a great hotel room close to the bus station. I wandered down to the nearby market area – all Uighur – and had delicious tender mutton kebabs, nicely spiced with cumin.

At this time of year, the available fruit is copious: small peaches, pears, watermelon, grapes and other sweet melons. Fruit has become a major part of my diet.

There is an obvious physical difference between the Uighurs and Han Chinese; it is estimated that the Uighurs are approximately 50% Caucasoid in background. They are also noticeably more friendly, with ready smiles and an ease of doing business that is quite pleasant. On the way to the Emin Minaret, a Uighur fellow on a motorcycle cart stopped and asked if I wanted a ride; he drove me the 4kms to the site, refused payment and then offered me a cigarette. On the way back the same thing happened! I stopped and had baked mutton dumplings. A Chinese fellow wanted to talk; he was married to a Uighur woman – so much for no ethnic mixing. A rumour is that Han Chinese are paid if they marry a Uighur.

Turpan Museum. This excellent, free museum shows the cultural and geologic history of the basin. There is a great mummy exhibition.

Emin Minaret. This splendid Afghan-style structure was built in 1777 by a Turpan general. Its bowling pin shape is decorated with a dozen brick motifs like flowers and waves. It is not possible to climb the minaret.

Around Turpan are many archaeological sites, only practically reached by a customized day tour. Most are underwhelming as the most interesting finds are all in museums: Astana Graves, Kerez Wells (museum to the Central Asian-style system of underground aqueducts), Aydingkul Lake (muddy, salt-encrusted but the second lowest lake in the world), Jiaohe Ruins (one of the world’s largest, oldest and best preserved ancient cities, impressive in scale rather than detail), Tuyoq (traditional Uighur village), Khocho Ruins (the Uighur capital from the 850-11th century, a few walls and Buddhist monastery still standing), and Bezeklik Caves (nice location but caves empty; one of its distinctive murals were cut out of the rock face by German archaeologists in 1905). The Flaming Mountains sounded nice but were a long way away.

I was keen to get to Urumqi to obtain my Kazakhstan visa which normally takes 5 days and I have only 4).

The temperature at 13:00 was 31°C with 10% humidity. It is a hot place. I took the bus 2½ hours north to Urumqi and the temperature was 10° lower. Snow-capped mountains rose above the low haze. The road followed a muddy braided river through a canyon surrounded by desolate rocky mountains.

URUMQI (pop 2 million)

It sprawls 20km across a fertile plain at the base of the Tian Shan. The modern skyline soon dashes any thoughts of spotting wandering camels, ancient caravans or a palm-fringed oasis. Business is done with all of Central Asia producing an exotic mix of people including Kazaks and Russians. But still, over 75% of the population is Han Chinese. Turpan was much more interesting.

I stayed at the LeiNiao International Youth Hostel, close to the centre of downtown. It turned out to be a great choice with a reasonable English-speaking staff.

The security here is unbelievable: swat teams patrol every block, armoured vehicles are on most corners, security checks are everywhere and thorough (bags are x-rayed and searched, water bottles and lighters confiscated, and everyone is frisked – almost friskers are women and they can be very thorough).

Obtaining a 30-day Kazakhstan tourist visa: the consulate is about 5kms north. Take BRT 1 to the Gaoxinjie station, cross to the east side of the street and walk north, turn right at the first corner, then left at the end and the consulate is about a block north. Go to the left door, wait at the far left desk and pay 20¥ to have the woman fill out the visa (she also made copies of my passport and Chinese visa), then go to the right-hand door and wait in line for a few hours to apply. Pay at the Construction Bank about a block away, return, wait in line again and hopefully your visa will be ready in 4-5 days. Neither a letter of invitation nor an itinerary letter are needed for most Western countries.

On my return from Tibet, I retraced my steps: a 14-hour train from Lhasa to Golmud, a 9-hour bus to Dunhuang, a 3-hour bus to Liuyuan and an overnight 9-hour soft sleeper to Turpan.

When I was originally in Turpan on September 6, I had decided to not go to the sights around the city, but this time (September 23), I had all day to kill before my train at 20:30. There were several touts selling tours, but they were all too expensive and there were no others to share. I tried to exchange my ticket to go to Kuqa during the day, but there were no seats. I eventually found a driver and a woman and her son and went to two places. The Kerez Museum (40¥) is all about the amazing irrigation system around Turpan. With thousands of kilometres underground, hundreds of wells, and above-ground canals and pools, it has made Turpan a major agricultural town. Grapes and raisins are the main crop but all kinds of melons, fruit and nuts are grown. Stalls around town sell an extensive variety of them all. The museum itself is underwhelming.

Jiaohe Ruins (70¥). This old city was established by the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220) as a garrison town. It’s one of the world’s largest (6500 people lived here), oldest (1600 years old) and best-preserved ancient cities, impressive in scale rather than its detail. Situated on a 2 square kilometre plateau 30m above the rivers that surround it, it was constructed by digging down, and building mud and rammed earth walls. There were several Buddhist temples, stupas and all the trappings of a large town – now all heavily eroded. Much was underground. The ruins are 8km west of Turpan.

Oddly, the regular train station for Turpan is 53 km north of the city, much farther out than the high-speed station. So it is a long drive to see both of these places. I had dinner at a street stall where everyone wanted to talk to me. We had a great time.

I don’t think I have ever seen a busier train station – every seat was full on two floors of waiting area and every inch of floor space was occupied. No white folks use this station. I caught the 20:30 train (hard sleeper) to Kuqa and on the train, a young woman told me what was going on. It is Muslim New Year, their biggest festival and everyone is heading home. Most on the train are young. When I had checked train availability for my last 10 days in China one month previously, there were almost no seats then (it pays to find out holidays and make reservations when necessary). I was told every Muslim business would be closed – no kababs or samsas.

KUQA (pop 77,000). Once a thriving city-state, this was a major centre of Buddhism. Here, the first Buddhist sutras were translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the 4th century. In the 7th century, its monasteries had 5000 monks. Many Buddhist caves are scattered in the area – most generally underwhelming.

The west end of town is Muslim with one-story businesses and housing. The east end is Chinese with high-rise apartments. Instead of the army, there is an overwhelming police presence. Twice guys had Rottweilers. The Han always demonstrate their control.

This was one of my oddest travel days. The train arrived at 5 am. My original plan was to store my backpack and see the few surrounding sites but there was no luggage storage. I sat on an orange chair outside the station, ate a bowl of granola and talked to a young guy. My train to Kashgar left at 00:37 so I had 19 hours to kill. The original plan was to see

Kazil Thousand Buddha Caves 75 km NW of Kuqa. Of the 230 caves dating to the 3rd century, only 6 are open at any time and only a couple have any real murals. Several caves were stripped by a German archaeologist and several were defaced by Muslims and Red Guards. The cost to get here was over 200¥, and as I have seen the best Buddhist caves in the world (Datong, Dazu, Dambulla, Mogao), it was just not worth it. Besides I was very sleep deprived and a day off would be welcome. So I caught a taxi into town and checked into the cheapest place in the LP at 120 for a room with no bathroom.

After sleeping and reading till noon, I caught the city bus to Qiuci Palace (55¥). This is the rebuilt residence of the Qiuci kings until the 20th century. There is a museum, several halls and a section of the Qing dynasty city wall – none very interesting. I walked back through the old Muslim neighbourhood. All doors and columns were brightly painted. For the festival, everyone was dressed in their Sunday best. Several houses were slaughtering sheep next to the street – tying their four legs together, slitting their throat, letting them bleed out into a hole dug in the boulevard, skinning them, cutting the head and feet off, and gutting them. The small intestine is stripped and tied off and all organs are thrown on the inside of the skin. I have seen this in New Zealand and Mongolia and always find it interesting to follow the anatomy. One guy had great manual dissecting skills.

I stopped for the tasty kebabs served with flat bread – all spiced with cumin and with big pieces of fat. After a vegetable market, the interesting stuff petered out and I took the bus back to the hotel. I read and slept until 6 pm when the manager of the hotel arrived, handed my money back and told me the police said I had to leave. I couldn’t get an explanation (I already knew that it was because I was a foreigner and we were not allowed to stay in budget hotels).

So I wandered down the street and watched the ubiquitous Chinese card game centred on a street shoemaker. I’ve watched it many times and have a pretty good idea of the rules. Shoemaking slowed the game considerably (crazy glue was an essential part of his armamentarium). A fellow left and I was invited to play; the first time that had ever happened. It was great fun and I probably broke even in the small-stakes game. It is Shithead (a common travel card game) with variations. Go to the Travelers Card Games post to see the rules.

I thought I would walk the 5 km to the train station, have some more kebabs (no samsas here) and finally get a taxi. I am not in Camino shape and my pack is heavy.

On the train, I met another great guy, Alex. He unusually had a Kindle and reads the Economist in English. It is uncommon to see Chinese read. When the sun finally came up, I thought there was snow on the ground. But it was extensive salination, the result of overwatering in desert conditions bringing salt to the surface.

As we approached Kashgar, there was a forbidding, eroded desert and mountains to the northwest and an oasis and green to the south.

KASHGAR (pop 350,000)

Locked away in the far westernmost corner of China, physically closer to Tehran and Damascus than to Beijing, Kashgar (Kashi) has been the epicentre of regional trade and cultural exchange for more than two millennia. Modernity has arrived as rail and planes connect to the rest of China bringing waves of Han migrant workers. Huge swaths of the old city have been bulldozed in the name of “economic progress”. But the spirit lives on as Uighur craftsmen and traders haggle in the bazaars. Kashgar is the access to the Southern Silk Road to Hotan, over the Torugart or Irkeshtam Passes to Kyrgyzstan or south along the Karakoram Hwy to Pakistan.

I stayed at the Kashgar Old Town Hostel, two floors of rooms surrounding a central courtyard. Most of the guests were Chinese but there were also more Western travellers than I have seen anywhere else in China – it was similar to Mongolia with a bunch of adventuresome types. A Swiss guy was on a four-year-long trip. Two Australians were just beginning their 20-month trip around the world. A German fellow, an architect working in Urumqi, plans on walking the 280kms to Tashkergan. Most were extensively exploring all the sites around the city.

Shipton’s Arch (Tushuk Tagh). This natural rock arch (actually hard dirt with conglomerate rock) is the tallest arch on earth with a vertical opening of 1200 feet. The first Westerner to describe it was the British consul-general in Kashgar, Eric Shipton, during his visit to the region in 1947. Successive expeditions attempted to find it without success until a team from National Geographic rediscovered the arch in 2000. The arch, located 80km NW of Kashgar is a half-day excursion. I rented a taxi with the two Australians and a British fellow for 500RMB. After paying the 45RMB fee, the arch is reached by a 30-minute hike on pavement, along a rocky creek bed and then through a narrow canyon upstairs to within about 40m of the arch itself. It is impressive, and magnificent in scale.

Grand (Sunday) Bazaar. Kashgar’s famous main bazaar is open every day but normally kicks it up on Sundays. I was thrilled that the reorganization of my trip had me in Kashgar on a Sunday, but because of the Muslim New Year holiday, it was closed! But the surrounding streets were busy with most of the same merchandise: kabab and samosas stalls, the smell of cumin, tubs of live scorpions, and all the usual souvenir shops. Take bus 20 from in front of the mosque.

Sunday Livestock Market. This happens only one day per week and was still on, so a bunch of us caught a taxi out to see the show. Uighur farmers and herders came from all over to sell their sheep, cows, goats and donkeys (there were no horses or camels). Trading is boisterous; animals are carefully inspected (they squeeze along the spine to access muscle and fat bulk, inspect the teeth, pick them up, feel the udders and scrotums), and haggling is full of smiles at too low bids, head wagging and orchestrated hand shaking ending with both shaking actively and big slap. It’s dusty, smelly, crowded and wonderful. The market is well out-of-town to the northwest and we couldn’t negotiate a fare less than 30RMB. Five of us took a slow motorcycle cart back to the closed market area.

Old Town. Sprawling on both sides of the road the hostel is on are alleys lined with Uighur workshops and adobe houses right out of an early-20th-century picture book. Some houses are 50 to 500 years old and the lanes twist haphazardly through neighbourhoods where Kashgaris have lived and worked for centuries.

It’s a great stroll. Sadly, the Chinese government has shown little affection for the old town and has spent more than 2 decades knocking it down, block by block. The shrinking pockets of very old neighbourhoods can be hard to spot; try the streets SE of the Night Market or the craft stalls north of the post office. One section, on a bend of the river has some houses 400 years old. But they are constructed of mud brick plastered with a mud/straw combination. I was invited into one, occupied by the 6th generation of a potter family. His pottery was simplistic and heavy but painted in vibrant colours. Even buildings made with clay-fired brick are held together with mud, not cement, and the whole place has either crumbled down or is about to and is not very earthquake-proof. How long are buildings built this way meant to stand and still function? The residential north of the park containing the Ferris wheel has been reconstructed and has been turned into a tourist trap with an entry fee. To the east stands a large section of 10m high section of Old Town walls, at least 500 years old.

Id Kah Mosque. Dating from 1442, this is the spiritual and physical heart of the city. Its courtyard and gardens can hold 20,000 people. Non-muslims cannot enter during prayer times. Like most mosques, I was uncertain if it was worth the 20RMB entry fee.

Mao Statue. A 30m-high standing Mao statue is in People’s Square. Statues of Mao are surprisingly uncommon in China. I have only seen two before.

Karakorum Highway. Going over the 4800m Khunjerab Pass on the way to Pakistan, this is one of the world’s most spectacular roads. For centuries, this route was used by caravans plodding down the Silk Road. A difficult-to-obtain permit is required to get right to the border and most tourists are only able to drive the 283 km to Tashgurgan. The border at the pass is another 100km past Tashgurgan and Pakistani visas are not available on arrival. It is a difficult visa to obtain and usually can only be done in your home country. The owner of the Kashgar Old Town Hostel is a pleasant Pakistani fellow who can expedite a visa in Beijing, Shanghai or Guanzhou in a week.

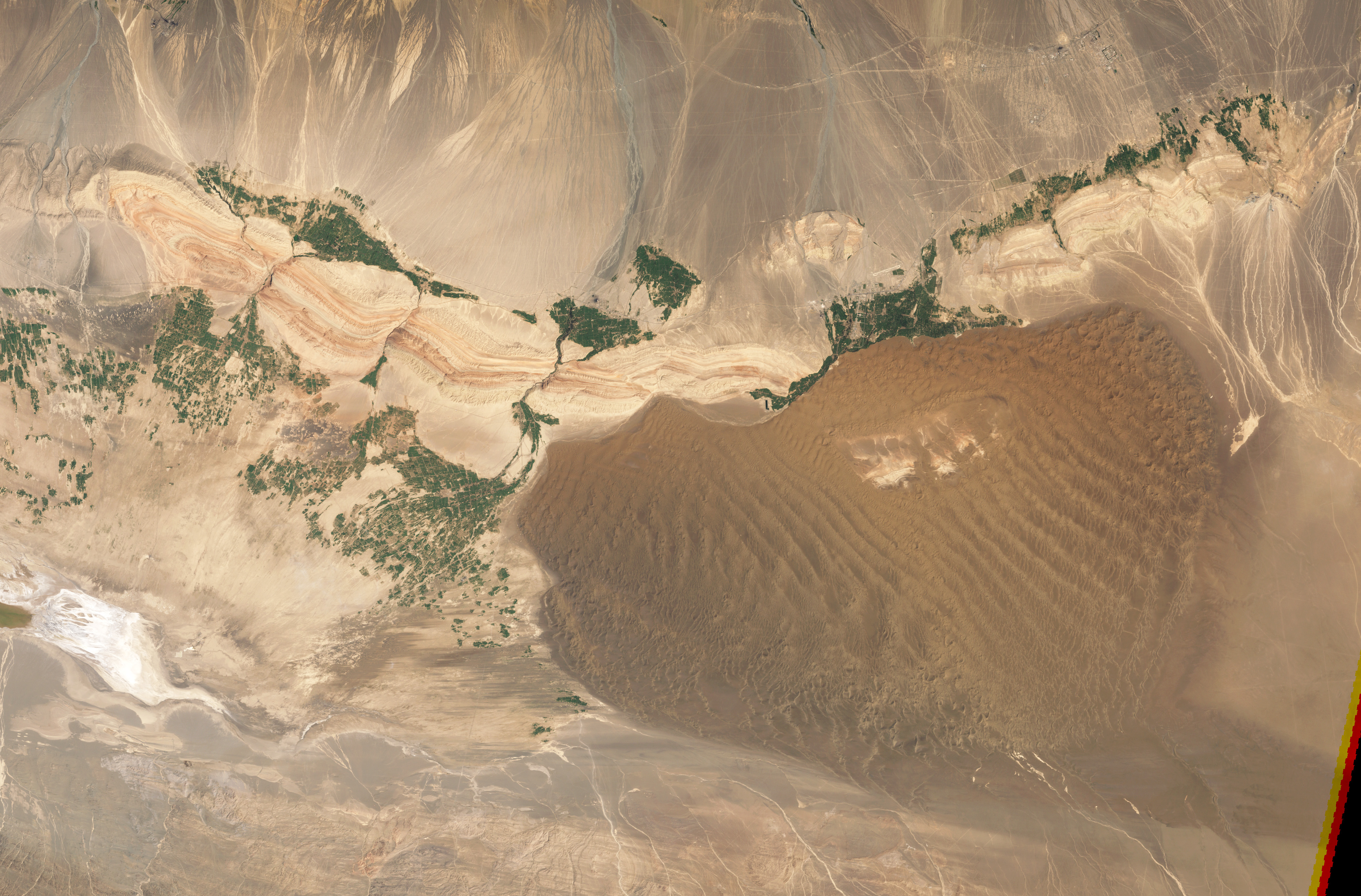

Catch a 6-hour bus from the long-distance bus station or for a more authentic experience, hitch-hike to Tashgurgan. Two hours and 118 km from Kashgar, you enter the canyon of the Ghez River with its red-brown sandstone walls. The road in the entire canyon was under construction. Chinese construction never ceases to amaze. Many crews are actively working to complete the highway before winter. Huge sections are being built on overpasses high above the river. The canyon is another example of incised erosion. The colour palette is quite spectacular, with claret-coloured walls at the beginning. A hydroelectric facility is being constructed in the canyon. The power plant is built and one fellow said a dam is being built with the whole project to be finished in 2017. To my thinking, it looks more like a run-of-the-river project. Glaciers in every mountain valley descend well below the snow line. After 3 1/2 hours, at the top of the canyon, you reach a huge wet plateau ringed with mountains of sand. Soon Kangur Mountain (7719m) and heavily glaciated Muztah Ata (7546m) appear. The main stopping point for views is Karakul Lake (194km) surrounded by glaciated peaks. Many tourists stop here overnight to stay in yurts (cost 60RMB including all meals!) and treks are possible. Then climb a pass with good views and meander through high mountain pastures dotted with camels and yaks before reaching Tashgurgan at 3600m. The indigenous Tajik people have a characteristic look with handsome narrow, dark faces. The women wear small pillbox hats and scarves.

Talking about adventurous travellers, one of the more hair-brained ideas was that of a young German who decided to walk the 280 km to Tashkurgan, averaging 40+ km per day. The first 90kms are flat but then it is progressively uphill. All walking is on a road, all dusty construction in the canyon. He was carrying a tent, sleeping pad and bag, a heavy propane burner, plus a lot of water. We looked for him from the bus but never saw him and he did not appear in Tashkurgan when we were there. Crazy.

The bus was an old rattletrap. The gas was filled by syphoning from a jerry can. Just after leaving Tashkurgan, the driver stopped at a pond behind the road, filled the radiator and got another big container to go. Besides the usual sheep, there were camels, donkeys and quite a few cows.

After returning from Tashkugan, I mailed postcards, changed most of my money to US$ (it took over an hour – Chinese banking is not very efficient), mooched internet at the hostel and caught bus #2 out to the airport (1RMB). The security was crazy: I rarely had to remove my plastic/nylon belt or thongs, and had a complete frisk with a wand. They even inspected the soles of my bare feet. We took off at 23:30 for the 1½ hour flight to Urumqi.

It was 2 am by the time I had my luggage. My flight to Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan was at 08:10 so it made no sense to get a hotel and I often sleep in airports anyway. The domestic terminal was completely closed and only the arrival section of the international terminal was open. They said we couldn’t stay there but I snuck upstairs to the completely dark, empty departure section and found some empty seats. It didn’t take long for a guard to kick me out into the cold – it felt about 0°C. So I found a place out of the wind, sat on my pack and curled up in my sleeping bag for a fitful 2-hour sleep. When the terminal opened at 5 am, I slept for another hour and a half and almost missed my flight. I jumped the cue at check-in, grabbed something to eat, and again jumped the cue through the long, painful security line and was the last person on the shuttle to the plane as it boarded very early.

Some observations on Xinjiang:

The Uighurs do not seem strongly Muslim. I have never heard a call to prayer and few are in the mosques at prayer time. In most Muslim countries, you are wakened at 4:30 am routinely.

If Muslims are not wearing clothing that gives them away (a cap for men, a head scarf for women), it is not always easy to tell them apart. They all tend to have slightly rounder eyes (but this is the least obvious as Uighurs are still 50% Chinese genetically), larger noses and a square jawline. For men: a heavier beard and facial hair (many older men have a beard with the lip and upper face shaven), For women: high heels, gaudy dress (bright colours, sequins), long stockings under nylons, lots of makeup, heavier build (when older, Uighur women are often overweight), and more buxom. Some of the Chinese I walked around with found the Uighur women more attractive than themselves. But it is all in the eye of the beholder. Headscarves often don’t improve appearance, and Muslim women always distance themselves from non-family men. There is a lot of untreated acne, much of it scarring, as many of the women excessively excoriate it.

My Mandarin/English phrasebook was often not of much use here. Most older Uighurs don’t speak Mandarin.