Why Israel needs a Palestinian state

Economist May 20th 2017

The victory of Israel over the Arab armies that encircled it in 1967 was so swift and absolute that, many Jews thought, the divine hand must have tipped the scales. Before the six-day war Israel had feared another Holocaust; thereafter it became an empire of sorts. Awestruck, the Jews took the holy sites of Jerusalem and the places of their biblical stories. But the land came with many Palestinians whom Israel could neither expel nor absorb. Was Providence smiling on Israel, or testing it?

For the past 50 years, Israel has tried to have it both ways: taking the land by planting Jewish settlements on it; and keeping the Palestinians unenfranchised under military occupation, denied either their own state or political equality within Israel. Palestinians have damaged their cause through decades of indiscriminate violence. Yet their dispossession is a reproach to Israel, which is by far the stronger party and claims to be a model democracy.

Israel’s “temporary” occupation has endured for half a century. The peace process that created “interim” Palestinian autonomy, due to last just five years before a final deal, has dragged on for more than 20. A Palestinian state is long overdue. Rather than resist it, Israel should be the foremost champion of the future Palestine that will be its neighbour. This is not because the intractable conflict is the worst in the Middle East or, as many once thought, the central cause of regional instability: the carnage of the civil wars in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere disproves such notions. The reason Israel must let the Palestinian people go is to preserve its own democracy.

The Trump card

Unexpectedly, there may be a new opportunity to make peace: Donald Trump wants to secure “the ultimate deal” and is due to visit the Holy Land on May 22nd, during his first foreign trip. The Israeli prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, appears as nervous as the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, seems upbeat. Mr Trump has, rightly, urged Israel to curb settlement-building. Israel wants him to keep his promise to move the American embassy to Jerusalem. He should hold off until he is ready to go really big: recognise Palestine at the same time and open a second embassy in Jerusalem to talk to it.

The outlines of peace are well known. Palestinians would accept the Jewish state born from the war of 1947-48 (made up of about three-quarters of the British mandate of Palestine). In return, Israel would allow the creation of a Palestinian state in the remaining lands it occupied in 1967 (about one-quarter). Parcels could be swapped to take in the main settlements, and Jerusalem would have to be shared. Palestinian refugees would return mostly to their new state, not Israel.

The fact that such a deal is familiar does not make it likely. Mr Netanyahu and Mr Abbas will probably string out the process—and try to ensure the other gets blamed for failure. Distracted by scandals, Mr Trump may lose interest; Mr Netanyahu may lose power (he faces several police investigations); and Mr Abbas may die (he is 82 and a smoker). The limbo of semi-war and semi-peace is, sadly, a tolerable option for both.

Nevertheless, the creation of a Palestinian state is the second half of the world’s promise, still unredeemed, to split British-era Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. Since the six-day war, Israel has been willing to swap land for peace, notably when it returned Sinai to Egypt in 1982. But the conquests of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were different. They lie at the heart of Israelis’ and Palestinians’ rival histories, and add the intransigence of religion to a nationalist conflict. Early Zionist leaders accepted partition grudgingly; Arab ones tragically rejected it outright. In 1988 the Palestine Liberation Organisation accepted a state on part of the land, but Israeli leaders resisted the idea until 2000. Mr Netanyahu himself spoke of a (limited) Palestinian state only in 2009.

Another reason for the failure to get two states is violence. Extremists on both sides set out to destroy the Oslo accords of 1993, the first step to a deal. The Palestinian uprising in 2000-05 was searing. Wars after Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000 and Gaza in 2005 made everything worse. As blood flowed, the vital ingredient of peace—trust—died.

Most Israelis are in no rush to try offering land for peace again. Their security has improved, the economy is booming and Arab states are courting Israel for intelligence on terrorists and an alliance against Iran. The Palestinians are weak and divided, and might not be able to make a deal. Mr Abbas, though moderate, is unpopular; and he lost Gaza to his Islamist rivals, Hamas. What if Hamas also takes over the West Bank?

All this makes for a dangerous complacency: that, although the conflict cannot be solved, it can be managed indefinitely. Yet the never-ending subjugation of Palestinians will erode Israel’s standing abroad and damage its democracy at home. Its politics are turning towards ethno-religious chauvinism, seeking to marginalise Arabs and Jewish leftists, including human-rights groups. The government objected even to a novel about a Jewish-Arab love affair. As Israel grows wealthier, the immiseration of Palestinians becomes more disturbing. Its predicament grows more acute as the number of Palestinians between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean catches up with that of Jews. Israel cannot hold on to all of the “Land of Israel”, keep its predominantly Jewish identity and remain a proper democracy. To save democracy, and prevent a slide to racism or even apartheid, it has to give up the occupied lands.

Thus, if Mr Abbas’s Palestinian Authority (PA) is weak, then Israel needs to build it up, not undermine it. Without progress to a state, the PA cannot maintain security co-operation with Israel for ever; nor can it regain its credibility. Israel should let Palestinians move more freely and remove all barriers to their goods (a freer market would make Israel richer, too). It should let the PA expand beyond its ink-spots. Israel should voluntarily halt all settlements, at least beyond its security barrier.

Israel is too strong for a Palestinian state to threaten its existence. In fact, such a state is vital to its future. Only when Palestine is born will Israel complete the victory of 1967.

PALESTINE – Dec 2017. Capital Failure – Why the Palestinians have never felt so despondent.

Blame poor leaders, distracted neighbours and a stalled peace process

Dec 19th 2017. Economist

The cause is Mr Trump’s decision on December 6th to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, while ignoring Palestinian claims to the city. The announcement has undermined America’s contention that it is a fair mediator. But it has also highlighted the decrepit state of the Palestinian national movement. Protests against the decision were relatively small—only a few thousand Palestinians turned out at their peak. Eight Palestinians were killed in the violence, but it was hardly on the scale of a new intifada, or uprising.

The Palestinians feel alone and despondent. Their cause has lost its resonance in a Middle East convulsed by civil wars and proxy battles between Iran, a Shia power, and Saudi Arabia, the region’s Sunni champion. Arab countries offered little more than empty condemnations of the Jerusalem decision. Saudi Arabia appears more interested in pleasing Israel, which has become a tacit ally in the conflict with Iran. The Palestinians say that what they have seen of America’s peace plan is insulting, but the Saudis have pressed them to support it. Even after Mr Trump’s speech, the Saudi foreign minister called his peacemaking efforts “serious”.

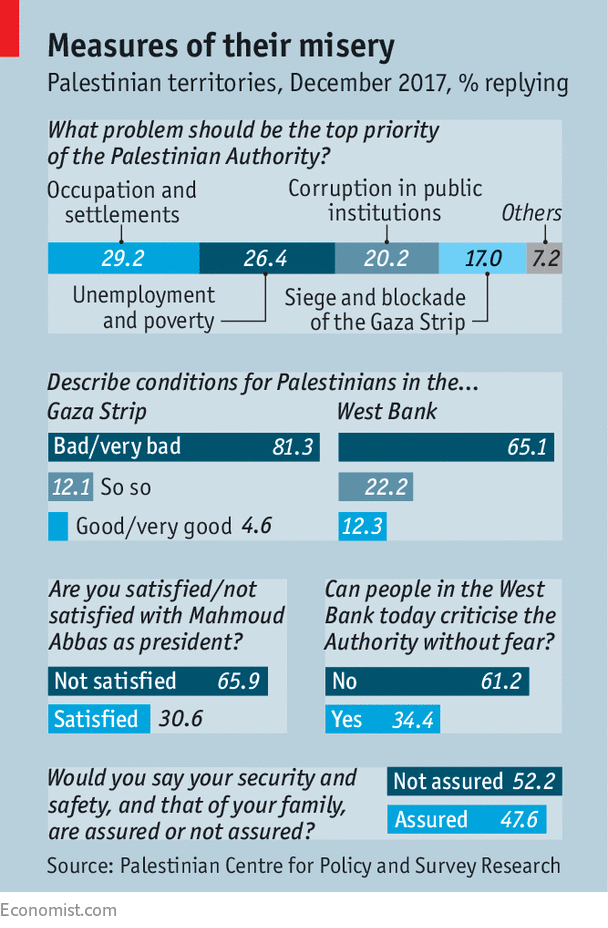

Ordinary Palestinians have more immediate concerns, such as food, water and shelter. In the West Bank young people dream of leaving for a better life in the West or the Gulf states. On the streets of Gaza, where Hamas once enjoyed broad support, it is now common to hear criticism of the group, and even nostalgia for the days when Israel controlled the territory. Asked to name the biggest problem in Palestinian society, fewer than a third cite the occupation. Many consider unemployment, poverty and corruption more urgent challenges (see chart).

National elections are eight years overdue. Many Palestinians have thus lost faith in politics. The only democratic exercise in recent years, a local election in May, had a turnout of 53%, down from 70% a decade earlier. The median age in the territories is 19, but the youngest plausible candidate to replace Mr Abbas is well over 60. With peace a dim prospect, many Palestinians are also losing interest in a two-state solution. A survey in August found that 52% of them still favour such a compromise. But support fell to 43% when the pollsters explained what a two-state solution might look like. There is also sharp disagreement over the alternatives, with roughly equal support for a binational state, an apartheid state, expelling the Jews and “other”.

Far from being the man to deliver a deal, Mr Abbas has become one of its biggest obstacles. He has little legitimacy to negotiate on behalf of his people, two-thirds of whom want him to resign. Increasingly authoritarian, he seems more concerned with domestic squabbles than the Israeli occupation. “His major goal is just staying alive in politics,” says Salah Bardawil, a member of Hamas. But Hamas has done no better.

It is telling that the one burst of successful Palestinian activism in 2017 came in East Jerusalem—where neither Fatah nor Hamas has much influence. When Israel installed new metal-detectors at the Al-Aqsa mosque in July, Palestinians staged protests and Israel backed down.

But some Palestinians living in the city are conceding the bigger fight. From 2014 to 2016 over 4,000 of them applied for Israeli citizenship, a threefold increase from a decade earlier. “The occupation isn’t going to end. Israel isn’t going away,” said a protester in July. “We don’t help ourselves if we pretend it will.”

PALESTINE 2021. Time for Abbas to Retire. New leadership is needed in the West Bank and Gaza.

The Palestinians deserve better than Fatah and Hamas

Jan 28th 2021

Mahamoud Abbas really knows how to show Israel the stuff he is made of. When the Israeli prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, mulled annexing parts of the West Bank last year, the Palestinian president stopped accepting transfers of tax revenue that Israel collects on behalf of the Palestinian Authority (pa). The move left the pa short of hundreds of millions of dollars and forced tens of thousands of civil servants to take salary cuts. Yet even after Israel suspended talk of annexation in August, Mr Abbas persisted with his protest. Only in November, facing a self-inflicted cash crunch, did he quietly relent.

This is what passes for leadership in the occupied territories. Though Israel bears much blame for the suffering of its neighbours, the pain is compounded by the self-defeating policies of Palestinian leaders. The stubborn men who rule the West Bank and Gaza often seem more concerned with preserving their own power than with improving their people’s lives. Palestinians deserve better.

True, the pa, which runs the West Bank, has been making some more encouraging noises of late. It has resumed co-operating with Israel on security and plans to reform its policy of giving money to the families of Palestinians whom Israel jails for such things as murdering Israelis—which American politicians tastelessly call “pay for slay”. Most important, Mr Abbas has announced that legislative and presidential elections will be held in May and July, after 15 years without a vote.

But can anyone trust Mr Abbas? He is in the 17th year of a four-year term as president. He has announced elections before, only to call them off. If they do take place, they will probably be a stitch-up between Fatah, Mr Abbas’s party, and Hamas, the militant Islamist group that runs Gaza. The past decade and a half has shown that neither is fit to govern.

The last time the Palestinians went to the polls, in 2006, Hamas beat Fatah in legislative elections. That led to a civil war which left Hamas in control of Gaza. The militants have since turned the territory into a corrupt, oppressive and miserable one-party state. They blame Israel’s blockade of Gaza for the fact that jobs, electricity and drinking water are scarce, which is fair enough. But it is the militants who hog precious resources and store weapons on civilian sites, making them targets. Their attacks on Israel achieve little besides prolonging their own people’s misery.

Things are better in the West Bank, but not much. It too resembles a one-party state, under Fatah. Mr Abbas rules by decree, with no hint of accountability. Though he is 85, he refuses to groom a successor, lest it speed his long-overdue departure. The president and his geriatric coterie of loyalists inspire little confidence, even from putative allies. “With those people, it’s hard to trust them or to think you can do something to serve Palestine in their presence,” said Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a former Saudi spy chief, on Saudi television last year.

Israel, to its shame, fosters Palestinian dysfunction. Its blockade of Gaza, with Egypt’s co-operation, has turned the territory into what many see as “an open-air prison”. Mr Netanyahu shows no interest in a fair peace deal. Nor do any of the contenders vying to replace him in an election scheduled for March. A popular rival, Gideon Sa’ar, has called the two-state solution an “illusion”. No wonder a sizeable number of Palestinians favour confronting Israel through armed intifada.

Israel, however, is not to blame for the failure of Fatah and Hamas to reconcile with each other. Nor is its blockade the only reason life is so grim for Palestinians. Their own leaders have failed them. In the midst of a pandemic, they have not bothered to ask Israel to share its supply of covid-19 vaccines. President Joe Biden has promised to renew aid to the Palestinians and restore diplomatic ties (broken by Donald Trump), but he can or will do only so much for them while they have such awful leaders.

Mr Abbas and his counterparts in Hamas should step aside for fresher, less tainted faces. Ordinary Palestinians should have a free, fair chance to pick a new government. There is no guarantee that this will make things better. Opinion polls are unclear and many voters still find militancy appealing. But there is little chance of meaningful reform unless today’s leaders step down. Voters should be allowed to choose a new government, and to sack it after four years if it blunders.