ROYAL SITES of IRELAND

Tentative World Heritage Sites (2010), represent the locations of the early kings of Ireland prior to about 1200.

1. Cashel in Tipperary.

2. Dun Ailinne

3. Hill of Uisneach in Westmeath

4. Rathcrogan Complex in Roscommon. Near the village of Tusk, it is a rich array of ringforts, earthworks, standing stones, and caves, and the source of many of Irelands mythological areas. According to The Annals of the Four Masters, it was here that Medb, the warrior queen and earth goddess who features heavily in the Tain Bó Cúailnge, sited her Cruachan, the location of the epic’s opening and gory conclusion. I didn’t go here (it is very out of the way and as a result, include most information on it here).

5. Hill of Tara in Meath

EARLY MEDIEVAL MONASTIC SITES

Also tentative World Heritage Sites (2010)

1. Clonmacnoise in Offaly County

2. Glendalough south of Dublin in Wicklow

3. Kells in Meath County.

4. Monasterboice and Mellifont Abbey in Lough County

5. Inis Cealtra in Clare County

TIPPERARY COUNTY

In contrast to squat, coastal Waterford, is the wealthiest of Ireland’s inland counties, deriving its prosperity from the flat and fertile plain known as the Golden Vale with dairy farms and horse breeders. Over 100kms from top to bottom, the southern half has most of the attractions.

ROCK OF CASHEL Cashel derives from the Irish Caiseal, meaning ‘stone fort’. The Rock refers to the entire complex of buildings on top of the rocky outcrop of limestone rearing out of the surrounding fertile plain, the Golden Vale. This is a tourist hotspot – visit early or late to miss the crowds. Despite its location and billing, the vista may be the best thing here as it is far less atmospheric than other ecclesiastical complexes like Kell Priory and Quin Abbey.

Make sure to take the excellent free tour. Most of the following is the verbatim text from the tour.

History and Buildings. A fort was originally here in the 5th century and used by the local kings. In 978, the Dàl Cais led by Brian Boru became the overlords of Cashel and subsequently all of Ireland in 1002. His descendent Murlagh granted the rock to the Church in 1101. The site had only one access road and one well.

An early medieval cathedral was built – all that remains is the 30m Round Tower. Round towers are built only at churches primarily in the 8th and 9th centuries when Ireland still had forests and few roads. They were high enough to stick up above the trees drawing people to the ‘safe’ church and for conversion. They were also bell towers and had conical stone roofs. Only lime mortar can be used in these buildings as it doesn’t attract water like cement. Most are dry-stone and mortar was primarily used to wedge the rock and keep them straight. The wood door was at least 3-4m above the bottom as the bottoms are solid rock to provide a good foundation (the foundations are only about 1m deep). The floors inside were also wood and good for storage but poor places to take refuge in an attack as they simply set fire to the door and it spread easily upward. 50 years later, the papacy established four archbishoprics in Ireland, one at Cashel.

Cormac MacCarthy took 7 years to build Cormac’s Chapel of yellow sandstone (that contrasts with the grey limestone of the rest of the Rock) finishing in 1134. The walls and roof were a meter thick and eventually became completely saturated with water. The stone carvings under the roofline are grotesques used to scare off spirits not gargoyles (have water coming from mouths). It took 8 years of being covered with scaffolds and a roof to dry out and was reopened in 2016. The roof and exterior unrendered stones were all repointed so water runs off. When I was there the inside was closed to deal with dust damaging the frescoes painted in reds, blues, and yellows: the baptism of Christ on the south wall and on the ceiling scenes of the Magi (although you wouldn’t know it unless told).

Between 1230-1279, the huge gothic St Patrick’s Cathedral in typical Anglo-Norman form (pointed arches and high set lancet windows) was constructed. Oriented to face east to take advantage of the rising sun (important the further north one goes to convert pagans, not as later claimed to point to St Peter’s in Rome), 5000 people could gather at one time and the transepts had separate chapels to divide up the crowds. The windows originally covered in inexpensive hides were made significantly smaller in the 15th century when expensive stained glass was added. Stained glass was important to educate and inspire the largely illiterate populace. A high walkway below the windows kept the bishop at a more authoritarian height – the imagery was everything. The belfry with its crossed rib arches in the crossing of the north/south transept has the only intact roof in the cathedral. The floor had several 16th and 17th grave slabs moved in from the graveyard where they were getting damaged. A leper’s squint is a tiny window placed at an angle so that lepers could see the service but couldn’t be seen themselves. The earliest intact tomb in it dates from 1574 (all others were destroyed by Cromwell and friends). The exterior and interior walls have the original square holes used to erect scaffolding – they were never filled in with stone as they knew Cashel would need repairs during its long life.

The graveyard is still active but one needs to be registered by 1930 to get a spot and only a handful of prospects remain.

The 15th-century Tower House sits on the west end of the cathedral. It had a defensive purpose and was a cold and dark living quarter due to its narrow windows. Stone floors were necessary to prevent fires. Reeds covered the floor in winter and straw in summer to provide warmth. The front has collapsed after a vicious storm. The stone from the collapsed wall was used to build a chapel in Wisconsin.

The Vicar’s Choir Hall is the last building of the Rock of Cashel built in the 15th century and now serves as the entrance to the site. The 8 men of the choir lived here. Watch the good video and see the frescoes being repaired in Cormac’s Chapel here. Outside is St Patrick’s Cross, unusually a Latin cross not Celtic. Christ on the cross is robed, as was the custom then. Made of sandstone, it has been ravaged by the weather: one arm are missing, face heavily damaged and one side support is gone. The one outside now is a copy and the real one is in the choir hall museum. The massive piece of rock came from 15 km away and was transported on the nearby River Shannon. To see what the real cross would have looked like, Google the Under 21 hurling championship cup.

The site was named a national monument in 1869, the first in Ireland.

The Midlands – OFFALY & WESTMEATH COUNTIES

Most tourists motor through this part of Ireland, mostly dairy farms and some large lakes. The River Shannon is the Midland’s western border and only Clonmacnois and Birr, both just over the border from Tipperary have much interest.

BIRR CASTLE

Actually, in Offaly County just outside the Tipperary border, it is north of Cashel and 45 km south of Athlone. The drive from Cashel was on an amazing straight road through flat country.

The castle, home to the Parsons family, later the Earls of Rosse, is still a private home and can only be seen from a distance. In the 19th century, Parsons gained an international reputation as a scientist and inventor. The third Earl devoted himself to astronomy and in 1845 built the huge Rosse Telescope with a 72-inch reflector, the largest in the world until 1917. It was fully reconstructed in the 1990s along with the massive, elaborate housing of concrete walls, tracks, pulleys, and counterweights needed to maneuver the huge 2m-diameter and 17m-long barrel built of wood staves. He was the first to see the Whirlpool Galaxy and try to explain the universe. The fourth Earl was an eminent photographer, and his brother built a small flying machine and a helicopter in the 1890s along with making artificial diamonds and the first steam turbine. All is detailed in the Science Centre in the coach houses.

Besides the telescope, the real draw is the gardens with the 50 most significant trees including the largest grove of giant redwoods outside California, a lake, wildflower meadows, the oldest wrought-iron suspension bridge in Ireland from 1820, and the formal garden with 300-year-old box hedges and canopied paths. One could spend hours touring them.

Clonmacnois. Pre-Norman Ireland’s most important Christian site sits on an idyllic location on the banks of the gently meandering Shannon River. The flat land floods every winter, some of the last type in Europe. The meadows become the summer home to rare wildflowers, grazing cattle, and birds.

History. The monastery was founded by St Kieran in 548, a disciple of St Enda on Inishmore on the Aran Islands. Kiernan brought with him a dun cow, whose hide later became Clonmacnois’ major relic and status as a pilgrimage site – anyone lying on the hide would be spared the torments of Hell. It was commemorated in the Book of the Dun Cow, the oldest surviving manuscript written wholly in Irish. Perfectly situated at the junction of the main road between Dublin to Galway and on the major north-south artery, the Shannon, provincial kings endowed the monastery with churches and high crosses. Between the 8th and 12th centuries, it was plundered over forty times by the Vikings, Anglo-Normans, and Irish enemies, and church reforms greatly reduced its influence. In 1552, Athlone’s English garrison reduced it to ruins, but as the burial place of Kieran, it has persisted to this day as a place of pilgrimage.

The three magnificent high crosses are in the visitor’s center. The Cross of the Scriptures, erected in the 10th century, shows the Crucifixion, Christ in the Tomb, and the Last Judgement. The South Cross and the North Cross are about a century older and much simpler. High crosses were inside at the cardinal directions, outside at entrances, used as protective barriers, and the focal point of meetings. Also here are several wonderfully carved gravestones, too small to serve as grave slabs.

Most of the nine churches are structurally intact except for their roofs. The cathedral has a 15th-century north doorway featuring decorative Gothic carving. The last High King of Ireland, Rory O’Connor was buried on the altar in 1198. Temple Clarán is the burial place of St Kieran. A fine 1124 round tower is in the western corner and another round tower with an intact conical stone roof is attached to 1160-70 Temple Finghan.

Time your visit to avoid the coach tours. I slept here overnight in wonderful solitude

Hill of Uisneech

One of the Royal Sites of Ireland, this 569-foot hill sits in the geographic center of Ireland halfway between Athlone and Mullingar in Westmeath County. It is in private land but walking corridors are marked off. A sign at the entrance says Fire Festival at Uisneech.

Park in the first lot, go to the visitor center (closed when I was there) and check out the sign to get the lay of the land. Then drive up the gravel road going north to another small parking lot with a small octagonal building.

Near here is a megalithic ring fort. Cross over the road and enter the field with a small lough on your right. There are 2 platforms, a tiny ‘hut’ on the edge of the lake, log seats around a fireplace, a log carved nicely into a bearded man, and an amazing large sandstone face statue with ivy and scallop shells for hair. The face has mosaic eyes and a mosaic ‘tattoo’ on one cheek extending to the forehead.

Continue on the internal road and grass to the top of the hill with its triangular survey marker. On a clear day, it is possible to see 20 counties from here and I could. Below is the Bealtaine Fire Ceremony Site.

Continue to Ail na Miream (also called the Cat Stone or the navel of Ireland), a huge glacial erratic that marks the center of Ireland. Eiru, after whom the country is named, was buried under the stone. There are several other sites if one has time to explore.

I doubt that this place gets many visitors except during the festival. Maybe it is the Irish Burning Man?

Kells. One of the Early Medieval Monastic Sites of Ireland, it was founded in 807 by the Columba monks who had abandoned Iona in the face of many Viking raids. They brought with them the celebrated Book of Kells, an illuminated copy of the gospels. After the disastrous Viking raid of 920, the great stone church of Kells was built, the city wall and a 90-foot-tall round tower with 5 windows, each looking at the 5 gates in the walls, each leading to an ancient road to the cities of Canon, Carrick, Maudlin, Dublin, and Farrell. The round tower, now without its conical roof, and three of the original great crosses are all that remain. The Cross of Patrick and Columba, beside the round tower, was erected soon after the monastery was built. The Market Cross outside the graveyard was used as a gallows after the unsuccessful 1798 Rebellion.

The Book of Kells was stolen in 1007 but found two months later covered by sod and lacking its richly decorated cover (it is in Trinity College in Dublin now). The Round Tower was mentioned in 1076 when Murcadh, the King of Ireland was murdered inside it. The churchyard wall, the boundary of the original church was rebuilt in 1711 but collapsed in 1997. Found to have no foundation it was rebuilt in 1998 with reinforced bulwarks. The present church is the plain, stucco Saint Columba Church of Ireland. Besides the graveyard surrounding the church and tower, is a square tower with an amazing 6-sided stone steeple built in 1783 by John Walsh, a stone cutter.

On a stone slab beside the church was the famous Charles Dickens quote from ‘A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

Cabra Castle, Kingscourt

In the SE corner of County Cavan, this castle is now a hotel about 3 km east of Kingscourt. The original Cabra Castle was confiscated in 1650 by Cromwell and given to Colonel Cooch. His descendants laid out the town of Kingscourt (Dun Na Ri in Irish). In 1808 the present castle was built and the original is in ruins in nearby Dun Na Ri Forest Park. It passed through the family but had to be sold in 1964 passing through three hands before finally being purchased by the Corscadden Family in 1991 who turned it into a hotel by adding cottages. This brought the number of beds to 107.

Inside it is a maze of small corridors and stairs dripping with old art, photographs, and armory. There is a history of ghosts, but just about every castle has these – it was voted the second scariest hotel in the world by Trip Advisor much to the surprise of its owners as no employee had ever seen one.

The hotel has hosted 16 US presidents and a bunch of Hollywood stars and is a common wedding venue. The grounds are lovely but the golf course looks like a total bore.

COUNTY LOUTH

DUNDALK. This moderate-sized city is in the north corner of Louth on the ocean.

Dundalk County Museum. This has the usual ‘city museum’ artifacts plus a room on its famous football teams and its industries through the ages.

Spirit Store. This is in the Nomad Mania ‘Things to do’ series. It is a quaint bar on the George Quay that fronts an inlet that dries completely at low tide. Well known locally, it often has live music from jazz to pop and traditional.

DROGHEDA. These were once two separate Viking towns on either side of the Boyne River. The town incurred the most infamous onslaught of Cromwell’s Irish campaign of 1649 when its defending garrison and many inhabitants were massacred by the Lord Protector’s army. In the late medieval period, the Irish parliament occasionally convened here. It thrived on exports of linen, shoes, and alcohol. The old docks have been revitalized as a shopping, bar, and restaurant scene.

Museum Mellifont. It has the usual assemblage of local artifacts, the best is on alcohol production in its 14 breweries and 16 distilleries and a collection of banners representing the various crafts and trades.

West of Drogheda are these two monastic sights.

Monasterboice. Another Early Medieval Monastic Site, was founded by St Buite in the 8th or 9th century but none of that remains. With the founding of the nearby great Cistercian monastery at Mellifont in 1142, it fell into decay. There is possibly Ireland’s best-preserved round tower (968) and one of Ireland’s finest high crosses, the St Muiredach’s Cross. The two church ruins are surrounded by a large graveyard dating from the 13th century with no connection to the then-defunct monastery.

Mellifont Abbey. Founded in 1142 by St Malachy, it was the first and subsequently most important Cistercian foundation in Ireland, eventually heading an affiliation of 20 monasteries. Set in a tranquil spot by the River Mattock, it must once have been an impressive complex, though its scant ruins leave much to the imagination.

After the Reformation, it was converted into a fortified residence. During the Battle of the Boyne, William of Orange based himself in Mellifont. It eventually was abandoned and fell ultimately into dilapidation. The tallest and finest remnant is an octagonal arched lavabo, where the monks washed. The remaining ruins rarely rise above waist height.

North COUNTY MEATH

BRÚ NA BOYNE (“the palace or the mansion of the Boyne”)

History. The first inhabitants of Ireland were hunter-gatherers with about 60% of their diet consisting of fish. In the Neolithic period around 3800 BC, they settled down to become farmers. 97% of Ireland was covered in forest that they cleared to farm wheat and barley and raise cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs, the same animals we have today. The average lifespan was about 28-35. They are the people who celebrated their dead in the great passage tombs of Brú na Boyne. Built on the Newgrange Ridge about 61m above sea level, they lived in wood huts below the River Boyne with its rich soils and water.

8 kilometres SW of Drogheda and due south of Mellifont, this Unesco World Heritage Site has spectacular 5000-year-old passage graves, high round tumuli raised over stone passages, and burial chambers. They are the largest megalithic tombs built in Western and Northern Europe. Besides the 3 large tombs of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, there are at least 37 more satellite burial mounds in the immediate area. The tombs are separated by about two kilometres.

After the displays in the visitor center and an audiovisual film explaining the relationship of the equinoxes and solstices to the orientation of the passageways, the actual sites can only be seen on a tour. The number of visitors per day is strictly limited and most are reserved, but by going at 9 am, it is usually possible to get in. A footbridge crosses the River Boyne to its north side and minibusses that have timed departures, shuttle you to the sites. There is no point coming later in the day as a full 3 hours is required to see them. Newgrange €7, Knowth €6

Both were constructed in the late Stone Age between 3200-3000 BC. Their purpose was primarily as burial sites, but they also served as reminders of the continuing presence of their ancestors, as territorial markers as they were built on hilltops, were centers of religious ceremonies and rituals, symbols of the huge effort put into their construction and as monuments meant to last forever. Showing great persistence, each took decades to build and only the last of them saw their completion. They are the oldest astronomically orientated structures in the world.

Around about 2000 BC, at the beginning of the Bronze Age, they completely abandoned the area for unknown reasons. The mounds though continued to be lived on. In the 7th and 8th centuries, a deep defensive ditch was dug inside the kerbstones of Knowth, tunnels were dug into their perimeters and the entrances to the chambers collapsed. King Tom lived here in the 10th century when they were part of the property belonging to Mellifont Abbey. People continued to farm on top until the 18th century.

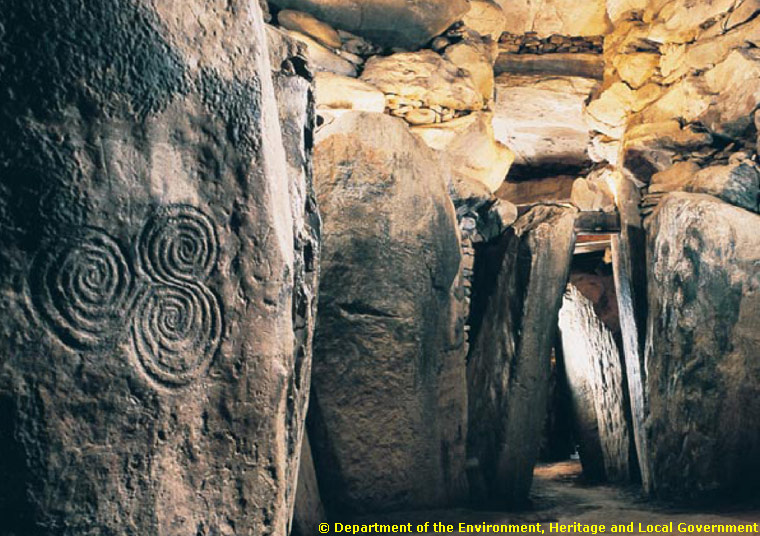

Their construction was carefully planned from the beginning. First, they planned the location of the passages by observing the timing of the solstices and equinoxes over several years. The large standing (orthostat) stones lining the passages were first decorated with petroglyphs by chiselling and pecking. Spirals, serpentine lines and concentric circles are the most common designs, but the exact meaning of these is not understood. 60% of all Neolithic art in Europe is at Brú na Boyne. Knowth was much better decorated than Newgrange.

These stones were then placed in sockets, covered with lintel stones and the sandstone or granite stone basins in the chambers were placed. Then the chambers were built with corbelled roofs of equally large stones – these were built first with the ceiling slab on the chambers placed last. and the kerbstones on the circumference of each tomb were placed. Alternating layers of material were placed on top: turf, cairn stones, clay, earth and stone, and finally more cairn stone, all orientated to provide drainage. 2000 large stones were used to build all the tombs: the grey kerbstones came from the coast about 14kms away in boats on the river and were brought up to the sites on wooden rollers. Some of the rock was quarried from rock outcrops 3-5 km north. The blocking stones covering the entrances were placed last.

The dead were cremated and the remaining bones and ash were placed in large stone basins. Probably it was the most important people of the community who were buried in the large tombs. Small quartz rocks from the Wickmore Mountains 80 km away and water-worn granite rocks from the Morne Mountains 40 km away were placed around the perimeter. It is thought that they were an important part of their culture until everything was abandoned.

The mounds were completely covered by grass and mature trees with cows grazing on top when Newgrange was “discovered” in 1699 by a farmer who luckily dug right over its entrance. The passageway of orthostatic stones was easily followed and documented and then left open for 200 years when the locals came and went as they pleased. Only the remains of 5 bodies were left for the eventual archaeologists. It was not until 1962 that O’Kelly did the real archaeological assessment that took over 40 years to complete as the mounds were completely excavated to discover all that is now known about these passage tombs. The passages in Knowth were only discovered when all 300,000 tons of covering material were removed. Then all the passage tombs were completely rebuilt.

Knowth. Built between 3200-3000 BC, it is the largest and most spectacular of the passage tombs – thought to be the largest building in the world when constructed. Surrounding it are 19 satellite tombs. It was excavated between 1973 and 1993.

127 massive kerbstones each weighing about a ton surround its circumference. Almost all are decorated with elaborate symbols. Besides the common whirls, concentric circles, and serpentine lines, one stone has a series of crescent moons, another a boat-like structure containing what appeared to me to be the stone basins and a third has two large crescents with finger-like projections facing central spiral. There are a total of 300 decorated stones at Knowth as most of the standing stones and chamber stones are carved.

It has two entrances, each with its chamber – its east entrance passage is orientated to point directly at the rising sun, and the west entrance points at the setting sun on the equinoxes (March 21 and September 21). At this time the sun is due east or west. Both passages are blocked and the two separate chambers cannot be entered. The tour is spent inside an excavated rectangular room with the much later constructed defensive ditch and a tunnel exposed.

A timber henge is constructed outside the entrance.

Newgrange. The contents were radiocarbon dated to 3200 BC. O” Kelly’s interpretation of its appearance is quite different than the archaeologist who excavated Knowth. He has reconstructed the façade with a 5m-high covering of small, white quartz stones with the granite stones placed regularly between the quartz. It only was done this way on about half of the circumference and only stone found at the time of the excavation was used. It has 97 kerbstones weighing up to 10 tons each and I only saw two with any decoration – spirals and zigzag lines.

Its entrance stone weighs one ton and is decorated with fantastic spirals and a serpentine line. 400 more large stones were used to construct the one passage and chamber. Unlike at Knowth, this chamber can be entered – the entrance has a box indentation cut over its entrance. The one passage is 19m-long extending into the center of the mound and ascends about two meters along its length before it arrives at the chamber.

The chamber has a cruciform shape with three side chambers containing two sandstone and one granite stone basin (also decorated) for the cremated remains. The larger right-side chamber is heavily decorated with its roof covered in spirals. The walls are made using irregular stones each weighing 4-5 tons stacked with a tilt for drainage and a lip – this is corbelling – so that the chamber slowly narrows to its 6-meter-high roof slab. Small ‘packing’ stones fill all the irregular gaps and are wedged so that water drains away from the chamber. The capstone is completely watertight and no water has entered the chamber for 5000 years.

This passage is orientated to the winter solstice. The roof box and slowly rising passage is crucial to allow the light to shine up the entire passage even with the entrance stone covering the door of the passage. On December 21st at 8:58 am, the light starts to shine on one wall of the passage and by 9:15 it is gone. The light shines up the passage for only about 6 days of the year – the rest of the time the chamber is completely dark. Amazingly there is no soot on any of the rock so they never used fire to light the chamber. My suggestion is that bones were only placed in the basins during this time.

Dowth. It is the least known of the three great passage tombs although it compares in size to the other two. It has 115 kerbstones and two passages facing westward. The smaller south tomb has a short passage and a circular chamber with a recess. The cruciform north tomb contains a large stone basin. Visitors cannot enter the chambers but can walk around the site which is not included in the tours.

HILL OF TARA

This small hill was the chief pagan sanctuary of early Ireland where ceremonies, burials, and rituals were performed. In the area are 25 earthworks and 50 more burial tombs. The five principal roads of ancient Ireland converged here. In about 4000 BC, a passage tomb (Duna na Grall) was constructed on the hill and was used for burials for the next 3000 years to the end of the Stone Age. A processional avenue (Tech Miachúarte) and henge (Rath Maeve) were constructed.

in the Bronze Age, funerary barrows were built and in the Iron Age, Rath na Rig was on the crown of the hill.

In the early years after Christ, it became the symbol of national kingship – to be crowned here was to be accepted as the king of Ireland. It was one of the Royal Sites and seats of the Gaelic kings: Cashel, Eman Macha (Navan Fort) for Ulster, Dún Ailinne Leinster, and Rathcroghan for Connaught. Therefore it was the seat of the king of Meath and the seat of the high king of Ireland. The greatest of the kings was Cormac Mac Airt and Conaire Mór

All that is visible today is the 8.3m ring fort right up against the wall of the church’s graveyard. Between 1899 and 1902, it was dug up by a cult, the British Israelites, looking for the Ark of the Covenant. The next tumulus is a passage tomb with a 4m passage built around 3000 BC (surrounded by a chain-link fence). More than 200 cremated burials were found here and the archaeological finds are in the National Museum of Archaeology. A circular depression on the east is the site of Cormac’s Residence. On the summit is the Stone of Destiny white phallic granite stone erected in 1814 to mark the burial of 400 United Irishmen killed in the Battle of Tara of 1798. The whole is surrounded by a 1km-long circular bank. There is remarkably little to see, but the views are great. There was almost no one here, all the people in the packed car park must have been eating lunch.

In 1843, Daniel O’Connell staged his biggest meeting here when up to a million people attended his campaign to repeal the Union with England. Free to see the site, €4 to watch the video.