Belgium – June 27-July 7 2018

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT BELGIUM

Bicycles. The Netherlands has a reputation for bicycles, but this place must be just as bicycle-mad. Virtually every road has bike lanes on both sides (usually in red brick or pavement). I am surprised that virtually no one wears a helmet, several rides with headphones (very dangerous), almost all bikes have panniers, a wicker basket, a baby carrier or pull a baby cart, and the vast majority are clunky-looking, upright handlebar street bikes. The lanes keep them out of the traffic, not like the suicide riders in the UK.

Food. Some unusual things are no fresh milk, only UHT; beef hamburger is not common and then finely ground with no fat, not very good for hamburgers – a beef/pork combination is much more common. Carrefour is ridiculously expensive but, like the UK and Ireland, there are Aldi and Lidl stores that offer good savings.

Gas. The cheapest is about €1.35/l, diesel is less than gas, but there are no tolls, so it ends up being a little less than in the UK. Prices vary widely.

English. Everyone speaks good English.

WESTERN FLANDERS

This area suffered greatly during WW I, but most were rebuilt with great style, especially Ypres and Diksmuide. Bruges and Ghent have wonderful medieval centres and are the true highlight of the area. The extensive sandy beaches provide relief from the sombre sight of battlefields.

I drove east along the coast, visited Bruges in one day, continued SE to Ghent and the drove SW to visit the Ypres area. June 27 was a sunny day with a high of 20, but it felt much colder with the stiff north wind blowing off the cold English Channel. It is much warmer inland.

Beaches. The beaches on the Atlantic coast are all gorgeous – hard-packed sand next to the water and sugary soft, beige stuff at the back. They must all be busy in the summer with all the hotels, restaurants, and apartments that back the promenades. But the English Channel misses most of the Gulf Stream and the water is relatively cold.

However, the back of all the beaches is lined with white, 8’ square sheds, slightly smaller than those in England, and to my mind, quite ugly. I asked at one of the beaches what they were for – they are simple storage sheds that people use to store their stuff when they are sunbathing. Go figure. They are usually rented for the entire April – September summer season and aren’t available for one day at a time, few are available for a week (cost depends on the month) and some are rented by the month. The cost for this 5-month season depends on the town: €765 at De Hann and closer to €1,000 for the bigger beaches a little north. Nobody sleeps in the sheds (although it looked like they were more beach houses in England).

Windbreaks of fabric strung between thin posts divide up the beaches. They are necessary for comfort as the common north wind is very cold (west winds just about always bring rain). Rental costs for other items/day: umbrella €5, simple cloth chair €5, reclining lounge chair €7. These windbreaks divide the beach among all the private providers who “own” their strip. Each section has its own colour and beach bar located in one of the sheds.

Only a few kids were wading in the water and fewer yet walking the beach. Everyone else was baking in the lee of the windbreaks. And on this cool Wednesday, there were a lot of people.

Every beach town has a wide promenade above the beach. Up here were all the “oldies”, bundled up in warm jackets. Statues are common on the promenades. Next come mostly apartments, some hotels, and several restaurants.

I drove east along the coast to visit all the following places.

Kusttram. Just across the border from France, this is in the NM “small town” series, but I don’t quite understand why. It is not on any map and is just an inland suburb of the city of Koksijde, one of the many resort towns that line the Belgian coast.

I decided to travel the local road next to the beach heading east. It is never that close to the beach and any views of the water are obscured by dunes.

A coastal tram, the Lijn, goes all the way from Knokke to De Panne/Adinkerke.

OSTEND (pop 69,000).

History. As a fortified port, it was ravaged by a 4-year siege in 1600-04 as the last ‘Belgian’ city to refuse Spanish reconquest. Later it blossomed as one of Europe’s most stylish seaside resorts. Most were bombed during WW II when German occupying forces (re)built the remarkable Atlantikwall sea defences that are today the city’s best sight. After the war, it was rebuilt as a grid of unaesthetic blocks. Today it is mostly a domestic seaside resort. Marvin Gaye lived here in a self-imposed exile from 1981-3 in an attempt to dry out from his drugged lifestyle. Two years later, in a state of cocaine-fuelled paranoia in Los Angeles, he was shot by his father.

The wide sandy beach has an ample promenade backed by tearooms with glassed-in terraces. The ho-hum hotels serve for any spillover from nearby Bruges.

The Thornton Bank is a vast wind turbine farm 30 km out in the English Channel. Boat trips to see the farm are available.

Mercator. This fully rigged, three-masted 1932 sailing ship was originally used for Belgian navy training purposes and since 1962 sits on an inland lake in central Ostend. It was renovated and reopened in 2017 as a nautical museum with rotating exhibits. The present exhibit was on a Belgian sailor captured by the Italians on Corsica in 1943, tortured and killed. Arctic traveller Adrien de Gerlache designed it and it was built in Scotland. It made 54 voyages. In 1956, it repatriated the remains of Father Damian from Molokai Hawaii. In 1960 it arrived in Antwerp and the next year was equipped as a museum ship becoming the pearl in Ostend’s crown.

Mu Zee. Ostend’s premier gallery, the third floor has local artists, the second rotating contemporary art ( on the architecture of images in the interwar period – not too interesting) and the ground floor an exhibit of James Ensor (1860-1945) who lived in Ostend for 40 years. While the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp is being renovated, his collection was moved here. He is an expressionist painter who I didn’t enjoy much. €10 concession for the whole museum.

Fort Napoleon. 3 km north in the suburb of Oosteroever, this is an unusually intact 1812 Napoleonic pentagonal fort. Constructed of red brick, an outer wall, a moat, and an inner fort made it impenetrable. There is little to see inside – half is a café and the part paid for held a modern art exhibit. Today it sits behind a large dune with no views of the ocean.

Atlanikwall. 6 km west of Ostend, this is an extensive, 2 km-long complex of WW I and WW II bunkers, gun emplacements and linking brick tunnels created by the Germans in each war. Most bunkers are furnished and ‘manned’ by waxwork figures.

Da Haan (pop 12,000) This is Belgium’s most compact beach resort. Its most famous visitor, Albert Einstein lived here for a few months after fleeing Hitler’s Germany in 1933. A century of land reclamation has advanced the beach 300m raising the promenade and obscuring any view of the water from the town. This is a small place, mostly hotels, apartments, and fewer glassed-in restaurants lining the promenade.

Blankenbrugge and Zeebrugge (the terminus of the ferry from Hull, England) are two more seaside resort towns I didn’t stop in.

Knokke-Heist (pop 34,000) This resort town is the preferred summer destination for Belgium’s bourgeoisie – and the beach had a remarkably different look than the others. The beach sheds were perpendicular to the beach enclosing glassed-in lounge seating. Likewise, the beachside of the promenade was mostly glassed-in sidewalk restaurants. Hotels and apartments extend for many blocks to the interior. The crowd was considerably younger than at De Haan.

HET ZWIN NATURE RESERVE. 3kms north of Knokke, this was once one of the world’s busiest waterways connecting Bruges to the sea, but in medieval times, the river silted up devastating Bruges’ economy. A marshy area was created that is now one of Europe’s main bird sanctuaries. The east end straddles the border with the Netherlands.

I drove here from the land side (parking €5 avoided by parking along the road, €3 to enter the reserve) but it can be seen from a distance by walking 2.8kms from Knokke (starting at the promenade at Surfer’s Paradise Beach Bar).

The good museum details all aspects of bird migration. 50 km of mostly forest walking trails skirt the main marsh and give access to several viewing areas looking down onto water channels and a small lake with a large island in the middle. An observation tower just outside the visitor’s centre brings you to eye level with a family of storks about 8m away. I missed the 3 pm stork-feeding. The reserve is bordered to the south by De Zwin dunes/forest/polder park with grazing ponies and West Highland cattle.

Ooskerke. A NM ‘small town’, it has cute white-washed houses and Sint- Wuuintinusker Church dating from 1089 with an enormous stone belfry and a much newer brick addition. The signs were all in Flemish, so I can give a little more information. It appears the town was liberated by Canadians in 1944.

Lissewege. A NM ‘small town’ this cute little village has pretty whitewashed cottages and an oversized brick church, Vrouwkerk (1225-1250) with great stone columns supporting pointed brick arches, a brick vaulted ceiling, intricately carved 17th-century grave slabs, oil paintings of the Ways of the Cross and when I was there, an exhibit of ceramic art with truly amazing pieces.

Stalhille. Another NM ‘small town (actually closer to Ostend), has Sint-Jan-de-Doperkerk, a brick church with a large central tower.

BRUGES (pop 117,000)

Central Bruges is one of the best-preserved medieval towns in the world and it has become a tourist mecca, especially during the summer. It is best at night with fabulous evening floodlighting and tries to come mid-week.

History. A fortress was originally constructed at the head of a long sea channel called the Zwin. Its medieval prosperity came from trading and manufacturing textiles from high-quality English wool. 13th-century traders were the first to formalize stock trading and to this day, stock exchanges are still called bourses in many languages and by 1301, Bruges citizens were very wealthy. Its zenith came in the 14th century when the Hanseatic League (a powerful association of northern European trading cities) set up international trading houses and ships laden with exotic goods from all over Europe and beyond docked at the Minnewater. In 1332, Venice merchants established a permanent office for luxury goods. Prosperity continued under the Dukes of Burgundy and at one point the population ballooned to 200,000, double that of London. Flemish art blossomed the city’s artists, known at the Flemish Primitives perfected painting that was anything but primitive.

A dynastic conflict between the French and Hapsburg empires in 1482 caused rising taxes and restrictions of the guildsmen’s privileges that sparked a decade of disastrous revolts. The townsmen imprisoned the Hapsburg heir, Maximilian of Austria for 4 months, the Hapsburgs took furious retributions and Bruges was forced to demolish the city walls. The Hanseatic League moved to Antwerp and many merchants followed. But most devastating of all, the Zwin gradually silted up so Bruges lost all access to the sea. The city’s economic lifeline was gone and the town was left full of abandoned houses, deserted streets, and empty canals. Bruges slept for 400 years.

The city slowly emerged in the early 19th century as war tourists passed through en route to the Waterloo battlefield. In 1892, Georges Rodenbach published Bruges-la-Morte (Bruges the Dead), a novel that beguilingly described the town’s forlorn but preserved charm. Curious wealthy visitors came and ever since the town has worked hard at renovations and embellishments to maintain its reputation as one of the world’s best-preserved medieval time capsules.

Antique Bruges escaped both world wars relatively unscathed and now largely lives off tourism. However, beyond the cute central area are industries making glass, electrical goods and chemicals, much of it exported via the 20th-century port of Zeebrugge, to which Bruges has been linked since 1907 by the Boudewijnkanaal (Baudouin Canal).

Old town Bruges is encased by an oval-shaped moat that follows the city’s medieval fortifications. The walls are gone, but four of the nine 14th-century gates still stand. The sights are all within easy walking distance as the centre is so compact. I began in the north and worked my way south through the old town.

Frietmuseum. The potato museum follows the story from its origin 10,000 years ago as the wild Andean potato in Peru to now with 4000 varieties, the most of any plant. It came to the Canary Islands in 1516 and spread through Spain and France arriving in Belgium in 1567. Belgium consumes the most of any country at 300kg-person/year and is #1 in eating them fried. The potato produces 16 tons/hectare whereas rice is only 3.8 tons/hectare. The biggest potato weighed 4.99kg and the longest was 26cm. Served alone they are not fattening as they are 80% water and 0% fat. In WW I, French-speaking Belgian soldiers offered chips to American soldiers and that is how they became known as French fries.

They are best cooked in their jackets to minimize loss of nutrients and are best fried in 2 stages: first at 140°C for 4-8 minutes to form a crust, shake to remove oil and let them rest, and then at 170°C for 2-3 minutes. The best oil is groundnut or sunflower oil. The museum also has displays of mustard, ketchup, and mayonnaise.

Fry shops in the Markt pay €100,000 rent per year.

Choco-Story. The very informative chocolate museum traces the cocoa bean back to the Mayans and Aztecs, its spread around the world – Ivory Coast 35%, Ghana 19%, Indonesia 14%, and Ecuador 14% are the biggest producers now. It requires a hot, humid, shaded environment to grow and only grows between 22° N and 21° S. Dark chocolate has no milk powder and only 7% cocoa butter and white has no cocoa paste.

At the end of the tour, you are treated to a very informative demonstration of how to make chocolates – and then we got to eat. You are given a small bar at the beginning and can eat as many wafers as you want throughout the tour. €11 with Frietmusuem.

Markt. This big open market square is Bruges’ nerve centre. It is lined with restaurants with eye-watering prices.

Belfort is the towering 13th century, 83m belfry – there is relatively little to see inside but panoramas from the roof include the wind turbines and giant cranes of Zeebrugge.

Historium takes you back to one year, 1435, using multimedia to produce an audio and video ‘movie’. It is a little light on the facts, is more suited to children, and is not worth the steep price. €14 for the cheapest “Explorer” Pass.

Burg. This square one block east of Markt has been the administrative hub for centuries. The southern flank has three superb interlinked facades.

Bruges Vrije has baroque gabling and golden statuettes. Once housing the administrative body that ruled Bruges from 1121-1794, it has an incredibly detailed oak carving above the black marble fireplace. Free

Stadhuis has a fanciful façade, all turreted Gothic excess, and an astonishing Gothic Hall. Free

Heilig-Bloedbasilitek. Morphing with the stadhuis’ western end is this basilica that takes its name from the phial supposedly containing a few drops of Christ’s blood and brought it here after the 12th-century crusades. The relic is brought out at 2 pm daily. The phial is mounted on a jewel-studded reliquary and paraded on Ascension Day for Bruges’ biggest annual parade. The inside of the basilica is wonderful with a wood barrel-vaulted roof, stone columns, and arches. €3 for the treasury.

Central Canal Area

Groeningemuseum. Bruges’s most celebrated art gallery, it has superb Flemish Primitive paintings (known for their meticulous realism especially the reflected light off the gold and gemstones) and a good exhibit showcasing artists from the 1880s to 1914. I enjoyed the informative descriptions of one sign in each room and the minimalist inscriptions next to each piece. €6 (several galleries were closed)

Gruuthuse. The courtyard is more interesting than the unsatisfying decorative arts exhibits inside. €8

Museum St-Janshospitaal. In the restored chapel of the 12th-century hospital, this museum shows medical instruments, sedan chairs, and what everyone comes here for, the superb masterpieces by the Flemish Primitive Hans Memling and the gilded oak reliquary of St Ursula (a Breton princess who made a pilgrimage to Rome with 11,000 virgins who were all murdered on their return journey by the king of the Huns).

St Salvatorskathedraal (St Saviors Cathedral). Subtowers top the massive 13th-century central tower. The ceilings are massively high and I enjoyed the many paintings and side chapels, one with a silver reliquary to St Eloi.

Brouweij De Halve Maan. There has been a brewery here since 1564, and the present one was founded in 1856, now owned by its 6th generation of one family. The first floor shows the brewing process, the higher floors brewing installations of past centuries, and the top roof has 360° views of the city (and an included beer). This brewery achieved notoriety for the 3276m pipeline under the streets of Bruges to its bottling plant. €10

Diamantmuseum. The idea of polishing stones with diamond dust originated in Bruges. The entire story of diamonds is presented well in a jumble of rooms. A diamond polishing demonstration costs €3 but I was unfortunately too late to see. €6 concession

GHENT (pop 250,000)

Ghent is small yet large enough to stay vibrant, and has medieval canal-side architecture and a gritty industrial edge. It is about 50 km SE of Bruges.

History. Ghent was a medieval cloth town and grew to become medieval Europe’s largest city after Paris and Constantinople. In 1540 they refused to pay taxes to fund the Ghent-born Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s military forays into France and the town’s privileges were revoked. This led to a long decline when most businesses’ moved to Antwerp. In the 19th century, it became the first town to harness the Industrial Revolution starting flax and cotton mills so that it became known as the ‘Manchester of the Continent’. Today universities and their docks are its lifeblood.

I purchased the 48-hour Ghent Pass for €30 which covers everything below and gives free rides on the Ghent tram and buses (the actual cost would have been over €50). I saw everything in one day on a long walk and then drove to the last three.

Ghent tram. This has 3 long lines giving good coverage throughout Ghent. I took it out to Museum Dr. Guislan.

Patershol. This web of twisting cobbled lanes has old-world houses once home to leather tradesmen, and now low-key restaurants and bars.

City Pavilion. Across from the Belfry, this open-air pavilion has a double-peaked roof of wood and glass windows. Locals call it the “sheep shed” and with its good acoustics holds music shows.

Belfort. Ghent’s soaring 14th-century belfry is topped by a large weathervane dragon. Climb to the top for the best views of Ghent.

St Baalskathedraal Cathedral (St Bravo). This towering church has fine stained glass and an unusual combination of brick vaulting and stone tracery. There is a whale skeleton behind the altar signifying Jonah and the Whale.

It has good art with pieces by Ruebens and Van Eyck’s 1432 masterpiece The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. €4 gets you into the painting kept in a special temperature-controlled, half-darkened chapel. If you don’t want to pay, a small copy is kept in side chapel 30, the sixth on the right beside the altar. Inside, pay €1 for the necessary audio guide.

It is one of the earliest major works of art ever untaken using oil paints. It’s had more than its share of adventures: it narrowly survived the Calvinists, was marched off to Paris during the French Revolution, two panels were stolen in 1934 and only one returned (the subject of an investigative thriller The Sacred Panel published in 2010), the second has never been found but a copy was painted to make the 12 panels picture complete, and was grabbed by the Germans during WWII who concealed it in an Austrian salt mine. The nudity of Adam and Eve so horrified Austria’s Emperor Joseph II that he had them replaced with clothed versions. Since 2017, individual panels have been periodically removed for restoration at MSK.

Gravensteen. The Counts of Flanders 12th century stone castle has moats, turrets and arrow slits. It was converted into a cotton mill in the 19th century, it has been restored – the guillotine and methods of torture were rather gruesome.

Huts van Alijn. This restored 1363 children’s hospice complex displays everyday life from the 1890s to 1970s. The top floor is all about Feesten, the annual festival held in Ghent (the 175th anniversary is in 2018) and the section across the square shows Belgian life month by month.

Design Museum. The collection here specializes in furnishings from art nouveau, 1970s psychedelic to 1990s furniture as art. It was surprisingly interesting, especially with the large display by Belgian designer Maarten van Severen.

MIAT. A 5-floor, 19th-century mill factory, it shows Ghent’s history in textile production and examines the social effects of 250 years of industrialization. Unfortunately, the individual signs are only in Flemish and you need to refer to an inconvenient paper guide. A very extensive collection of heavy mechanical weaving equipment comes deafeningly alive on Tuesdays and Thursdays at around 10 am.

Greater Ghent

Museum Dr. Guislan. This psychiatrist (1797-1860) introduced many humane additions to psychiatric thinking. The museum is spread around a gorgeous 1857 psychiatric hospital about 3 km NW of the town centre. The tram stops just outside the gates. Most is on the history of psychiatry with displays on Xrays and modern scanners. There are also large art galleries done by patients and staff.

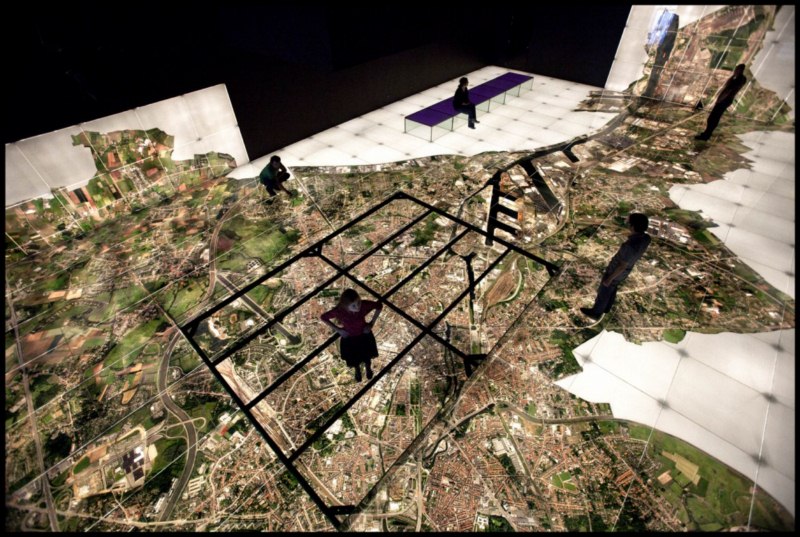

STAM (Stadmuseum Gent). All about the history of Ghent, this well-done museum is housed in another beautiful old building, once an abbey. A highlight is a photograph on the floor under a scale model of the city. The large panels in each room give a good overview in English but the individual descriptions are only in Flemish.

SMAK (Stedelijk Museum voor Actuel Kunst). Ghent’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in a wonderful building with enormously high ceilings, has changing exhibitions of provocative, cutting-edge installations, none of which I liked much. Do these guys get paid for producing this stuff? This gallery is about 4kms south of central Ghent.

MSK. Across the road from SMAK, the fine art gallery showcases all the great Belgian and Low Country painters from the 14th to the 20th century. It is housed in another beautiful 1903 building.

Duerle. Another NM “small town”, was truly senseless. Only about 5kms west of Ghent, it was a very high-end bedroom community for Ghent with mammoth homes on big lots, and not a business or church or belfry. Go figure out why it is on the list.

OUDENAARDE. About 15 km south of Ghent on the way to Ypres, this small Flemish city grew wealthy in the mid-16th century as local weavers switched to tapestry weaving. Enormous Oudenaarde wall tapestries, filled with exquisite detail and luminous scenes of nature, nobility or religion, were in great demand by French and Spanish royalty. But by the end of the 18th century, wars had caused serious trouble and the industry all but disappeared.

It hosts the last stage of the Tour of Flanders bike race.

Stadhuis. The impressive market square is dominated by a gorgeous 1536 town hall topped with a central belfry spire.

MOU. Within the Stadhuis, this displays silverware and a dozen faded but priceless 16th-century Oudenaarde tapestries.

St-Walburgakerk. This imposing church is a combination of 13th-century chancel and 15th-century Gothic tower. Inside are numerous paintings and tapestries.

PAM Ename. 3 km north of Oudenaarde, in AD 925, this was one of the three main defence posts along the border between pre-medieval France and Ottonian Germany. Later it was home to a vast abbey reduced to rubble after the French Revolution. The village is now a drab suburban village.

KORTRIJK (pop 76,000). Founded as the Roman settlement of Cortoriacom, it grew wealthy as a flax and linen centre but was severely bombed by the Allies in WWII. It was the venue for Flanders’ defining medieval battle.

Battle of the Golden Spurs. Flanders’ French overlords were incensed by the Bruges Matins massacre of May 1302. The French king sent a well-equipped force against a ragged, lightly armed force of weavers, peasants, and guild members from Bruges, Ypres, Ghent, and Kortrijk. But they have laid a cunning trap, the Flemish had previously disguised a boggy marsh with brushwood. Snared by the mud, the heavily armoured French were quickly immobilized and slaughtered, their golden spurs hacked off and displayed as trophies in Kortijk’s church. It was the first time professional knights had ever been defeated by an amateur infantry and the event became a potent symbol of Flemish resistance. July 11 is still celebrated as Flanders’ national holiday. The battlefield site is no Groeningheveld, a leafy park in central Kortrijk.

Kortrijk 1302. This modern experience museum explains the battle. The English language audio guide is essential to follow the multiple video screens, but it is all disappointing and unsatisfying, especially for non-Flemish visitors. The 14-minute movie climax offers the self-deprecating conclusion that the battle’s importance has been overblown.

Dud Rekem. A NM small town, the houses are red brick, and the church is an amalgamation of a stone tower and red brick addition. The weather vane is a lovely rooster.

Rampaffairz Skatepark. Just west of Kortrijk, this indoor park has plywood ramps and tricks. €8.50/day

YPRES SALIENT

The Ypres Salient was formed by the Allies to repel the invading German army before it reached the strategic North Sea ports in Northern France. The area’s line of barely visible undulations provided enough extra elevation to make good vantage points and were prized military objectives. Hundreds of lives were lost in numerous bids to take these very modest ridges. The first battle of Ypres in October and November 1914 set the lines of the Salient. After that, both sides dug in and gained relatively little around for the remainder of the war, despite three valiantly suicidal battles that followed. The most infamous of these came in the spring of 1915 when Germans around Langemark launched WWI’s first poison gas attack. It had devastating effects on the advancing Allied soldiers and on the Germans themselves. On 31 July 1917, British forces launched a three-month offensive commonly remembered as the Battle of Passendale, the ‘battle of the mud’. Fought in shocking weather on fields already liquidized by endless shelling, this horrifically futile episode killed or wounded over half a million men, all for a few kilometres of ground. These modest Allied gains were lost again in April 1918.

Flanders’s WW I battlefields suffered four years of senseless fighting during which 850,00 Allied soldiers lost their lives. Whole towns disappeared into a muddy, bloody quagmire. The fighting was fiercest in the ‘Ypres Salient’, a bulge in the Western Front with poison gas, tunnels, and trenches. The reconstruction of villages and replanting of trees took years, and even now farmers regularly plow up unexploded munitions. Today the pleasant farmland is patchworked with 170 cemeteries where rows of crosses stand in silent witness to all the wasted life.

Local museums show WW I memorabilia and dozens of painstakingly maintained war graveyards have regimented ranks of headstones. Concrete bunkers, bomb craters and trench sites would have been much muddier and unshaded as virtually every tree had been shredded by artillery fire.

North of Ypres

Deutscher Soldtenfrienhof. After the war, there were 678 German military cemeteries with 134,000 soldiers in Belgium alone. In 1925, the number was reduced to 128 and in 1954 to just four: Hooglede (8,247), Langemark (44,294 including 25,000 in a mass grave), Menen (47,864), and Vladslo (25,645). Initially, there were wooden blocks with a bronze plaque that were replaced by the current granite grave markers each commemorating 20 soldiers. Vladslo, amid oak trees, is best known for the two statues Grieving Parents created by Kathie Kollwitze whose son Peter is buried at the foot of the father’s statue. They are universal symbols for every parent who has lost a child to the tragedy of war and are renowned for their simplicity: the father is kneeling with hunched shoulders but his head is erect and the mother is kneeling but head bowed. Both have their arms crossed in front.

When I was here, in contrast to the Allied cemeteries, there were no other visitors.

Tyne Cot. Near Passendale, this is probably the most visited Saliente site, the world’s biggest British Commonwealth war cemetery with 11.956 graves. A huge semicircular wall commemorates 34,857 lost-in-action soldiers from the UK and New Zealand whose names wouldn’t fit on Ypres’ Menin Gate (which has the Canadian entries). Oddly there is one from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment – Second Lieutenant Barrett. Two dumpy concrete bunkers sit amongst the graves and the large central 1927 Cross of Sacrifice.

It was decided to not repatriate those who fought together should remain united in death. The dead remained where they fell, many were lost in the mud and then were taken to a large concentration cemetery. In 1919-21, they were reburied with a wooden cross eventually replaced by a headstone made of Portland cement. The cemetery seen today was completed in 1927.

Each grave has the regiment badge if from the UK, a maple leaf if Canadian, a harp if Irish, a springbok if South African, a fern if from NZ or a setting sun if Australian. If the body is unidentified, there is the inscription “A Soldier of the Great War” and “Known Unto God”. Religion is marked with a cross if Christian, Star of David if Jewish and none if religion is unspecified or Presbyterian Church of Scotland. There are rows of 6 different kinds of roses and in front of each grave are five types of flowers. The four gardeners in charge of this cemetery and the interns are all employees of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

I had a great tour of the cemetery from an intern from north England. She showed me some of the more interesting graves. Arthur Conway Young – Royal Irish Fusiliers 16/08/17 Born in Kobe Japan, has no religious sign and the inscription “Sacrificed to the Fallacy That War Can End War” so is presumed to have been a conscientious objector. J P Robertson VC 6/11/1917 was known as ‘Whistling Pete”, at 35 still a private as he had refused promotion. “Behold How Good and How Pleasant it is For Brethren to Dwell Together in Unity (Mother)”. There was also a Canadian Victoria Cross recipient.

SE of Ypres

Canadian Hill 62 Memorial. On a small rise called Mount Sorreland and up two wide staircases is this square granite boulder with the inscription “THE CANADIAN CORPS FOUGHT IN THE DEFENCE OF YPRES April-August 1916” and on the base “HONOUR TO CANADIANS WHO ON THE FIELDS OF FLANDERS AND OF FRANCE FOUGHT IN THE CAUSE OF THE ALLIES WITH SACRIFICE AND DEVOTION”. Around the boulder on the floor are the directions of the significant scenes of battle – all points of the compass are present.

The memorial is just past the Commonwealth Sanctuary Wood Cemetery.

Essex Farm Cemetery. This small cemetery originated in 1915. It is significant for the memorial to the Canadian Medical Doctor, Lt Colonel John McCrae (1872-1918) who wrote In Flanders Fields when stationed here as the medical officer for 17 days during the gas attack of April 22, 1915. Initially, the medical station was simply dug into the canal bank and then was replaced in September 1916 with the concrete bunker seen today. McCrae died in 1918 from pneumonia (I presume influenza) while serving at a Canadian Army hospital in Boulogne-Sur-Mer, south of Calais and that is where his grave is.

YPRES (IEPER pop 36,000)

in the Middle Ages, it was an important cloth town, ranking alongside Bruges and Ghent. In WWI some 300,000 Allied soldiers died in the ‘Salient”, a bow-shaped bulge that formed the front line around town. Ypres remained unoccupied by German forces but was utterly flattened by bombardment. After the war, the medieval core was convincingly rebuilt. Most tourism still revolves around WWI and related themes.

Lakenhalle. Dominating the large market square, this is one of Belgium’s most impressive buildings. Its 70m high belfry tower looks like Big Ben. The original 1304 building beside the Ieperslee, a river that, now covered over, allowed ships to sail right up to it. It is possible to climb the tower for €2.

In Flanders Fields. On the bottom of the Lakenhalle, this museum gives a moving introduction to WWI history using soundscapes, videos, exhibits, and interactive learning stations that allow you to become a character traversing the wartime period. €10

Menin Gate. This huge stone gateway straddles the main road at the city moat. It’s inscribed with the names of 54,896 ‘lost’ British and Commonwealth WWI troops whose bodies were never found. At 8 pm daily, traffic through Menin Gate is halted while buglers sound the Last Post in remembrance of the WWI dead, a moving tradition started in 1928. Sometimes it is accompanied by pipers, troops of cadets, or military bands.

Comines. This commune is an administrative curiosity, a detached enclave of Francophone Hainaut sandwiched between Flanders and France with Comines town cut in half by the Belgo-French border. The French side has the bulbous belfry tower meticulously rebuilt after WWI. The museum on the Belgian side celebrates the ribbon-making industry, Comines’ economic mainstay since 1719.