Kosovo – South, West, East May 8-10, 2019

TIPS for KOSOVO

1. Your vehicle insurance may not be valid in Kosovo. Mine wasn’t and insurance needs to be purchased at the border.

2. Google Maps doesn’t work well here. After you start Directions, there is no Start button, only Preview. The route is marked but there is no navigation and it requires refreshing every minute. There is no rerouting so making a mistake and missing a turn requires using unmarked routes to get to the marked one.

3. Currency: Euro

OBSERVATIONS for KOSOVO

1. Traffic seems to move very slowly – large trucks, buses, tractors (many), the many very slow Kosovo local drivers and horses or oxen pulling carts all keep the pace around some of the towns to about 50kms/hour.

2. There is a lot of farm traffic: many horses and even a pair of oxen were seen usually manned by an old guy with his wife on the back and pulling ancient wood carts. Tractors and odd machines that looked like rototillers with bicycle-like handlebars were everywhere. There is an odd golf cart-like contraption with a loud engine.

3. Kosovo people seem unusually friendly and nice. I had many chance encounters. Even though this is an almost entirely Muslim country, I did not see one head scarf or burka.

I crossed into Kosovo at about 5 pm. Again my car insurance was not valid here and it was necessary to purchase 15 days of insurance for €15. I also got the agent to take all the N Macedonian money I had as I never planned on returning there in the future.

Google Maps turned weird after entering Kosovo. Normally after you choose your destination, a small icon for Directions appears, then one for Start. Instead, it was Preview – only a route that disappeared was possible with no turn-by-turn navigation. This is the first time this has happened in my almost 16 months of completely relying on Google Maps, fine if staying on one road but much more difficult if there are any turns or you get off route as there is no re-routing. I downloaded Maps Me offline maps to use in Kosovo, but the same problem occurred (Maps Me doesn’t have Preview so there was no route at all). Kosovo is a real outlier (one of the four independent countries in the world that don’t belong to the United Nations) and possibly Google Maps are not registered here. I searched the problem and the latter is the explanation.

Immediately across the border, Kosovo is building a huge expressway to North Macedonia, much of it elevated on big overpasses. It must have been very expensive to build. Supposedly it was to be finished in 2018, it looked like it would be open very soon. I turned west to go through the Sar Mountains on the Macedonian/Kosovo border. The mountains were covered with more snow than I have seen so far. I got water from a stream. The road topped out at a pass with a resort village, then descended to Prizren. Besides all the horses pulling wagons, an old woman was herding a single cow through one town. Just before the town, it passes through a lovely narrow gorge.

PRIZREN (pop 86,000)

Prizren is a historic city located on the banks of the Prizren Bistrica River and the slopes of the Šar Mountains. The municipality has a border with Albania and North Macedonia.[By road the city is 99 kilometres (62 miles) northwest of Skopje, 85 kilometres (53 miles) south of Pristina and 175 kilometres (109 miles) northeast of Tirana.

History. It was the Roman town of Theranda. Bulgarian rulers controlled the Prizren area from the 850s, Slav migrants arrived in the area in the 11th century and the Byzantines took over in the early 11th century. Serbians arrived retaking the area in 1180-90 and again in 1208. The Ottomans conquered it in 1455 and it was a prosperous trade city and the cultural and intellectual centre of Ottoman Kosovo. It was dominated by its Muslim population, who composed over 70% of its population in 1857. The city became the biggest Albanian cultural centre and the coordinated political and cultural capital of the Kosovar Albanians. During the late 19th century the city became a focal point for Albanian nationalism and saw the creation in 1878 of the League of Prizren, a movement formed to seek the national unification and liberation of Albanians within the Ottoman Empire.

it was involved in the First Balkan War in 1912 and the Serbs killed 5,000 Albanians in an attempt to destroy the Islamic population. Most foreigners were barred from entering the city (but Leon Trotsky arrived and worked for a Ukranian newspaper there). 30,000 fled to Bosnia. 30 of the 32 mosques were turned into hay barns and military quarters.

In WWI, Bulgarians took over with forced Bulgarisation and 1,000 people died of hunger in 1917. By the end of 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed. In WW II, the Italians controlled the area. In 1944, German forces were driven out of Kosovo by a combined Russian-Bulgarian force, and then the Communist government of Yugoslavia took control.

For many years after the restoration of Serbian rule, Prizren and the region of Dečani to the west remained centres of Albanian nationalism. In 1956 the Yugoslav secret police put on trial in Prizren nine Kosovo Albanians accused of having been infiltrated into the country by the (hostile) Communist Albanian regime of Enver Hoxha. The “Prizren trial” became something of a cause célèbre after it emerged that many leading Yugoslav Communists had allegedly had contacts with the accused. The nine accused were all convicted and sentenced to long prison sentences, but were released and declared innocent in 1968 with Kosovo’s assembly declaring that the trial had been “staged and mendacious.”

The town of Prizren did not suffer much during the Kosovo War but its surrounding municipality was badly affected 1998–1999. During the war, most of the Albanian population were either forced or intimidated into leaving the town. About 30 were killed and over a hundred houses were burned. At the end of the war in June 1999, most of the Albanian population returned to Prizren. Serbian and Roma minorities fled. The community is now predominantly ethnically Albanian. In 2004, during the Unrest in Kosovo, some Serb cultural monuments in Prizren were damaged, burned or destroyed, such as old Orthodox Serb churches. Also, during that riot, the entire Serb quarter of Prizren, near the Prizren Fortress, was destroyed, and all remaining Serb population was evicted from Prizren.

The municipality of Prizren is still the most culturally and ethnically heterogeneous of Kosovo, retaining communities of Bosniaks, Turks, and Romani in addition to the majority of Kosovo Albanian population living in Prizren. Only a small number of Kosovo Serbs remain in Prizren and area, residing in small villages, enclaves, or protected housing. Prizren’s Turkish community is socially prominent and influential, and the Turkish language is widely spoken even by non-ethnic Turks.

Prizren Old Town. A NM “Sight”, everything south of the river is in Prizren Old Town – the fortress, Church of the Holy Saviour and Sinan Pasha Mosque.

There are two trails both starting at Shadren Square: The Journey of Stone climbs up to the fortress and the 90-minute Marash Trail follows the west side of the river and then climbs up to the fortress.

Church of the Holy Saviour. On the way to the fortress, this is a tiny brick/stone church occupies the NE corner of a high-walled courtyard. The gate on this side is locked and razor wire prevents access. Maybe it can be entered from the west?

Prizren Fortress. Built in the 4th and 5th centuries, the curved north wall has been completely restored with several casements and rooms. There are foundations of a 1808 mosque and a nice restored building housing a museum. Views down to the town are enhanced by a good sign that points out the landmarks and compares the view to Prizren in the old days.

Sinan Pasha Mosque. Next to the river, this large stone 17th-century mosque has a great portico with 3 domes. It was locked and didn’t open all morning so I assume it is not used?

Albanian League of Prizren Museum. On the north side of the river, the political and military organization League of Prizren was formed in this complex. It established the first Albanian government in 1881 and chose Prizren as its capital. In 1999, Serbian forces destroyed an important Albanian cultural monument in Prizren, the League of Prizren building, but the complex was rebuilt later on and now constitutes the Albanian League of Prizren Museum. In the round square next to the complex is a statue of the Prime Minister and ministers of foreign affairs and defence.

Brod (pop 900). In the NM “XL” series it is a village in the extreme southwest of the country, in the region of Gora, about half the people are Gorani, Muslim and speak Našinski. Gorani are traditionally known as good confectioners and a variety of foods.

GHAKOVA (Gjakove or Đakovica) (pop 41,000)

In the south-western part of Kosovo, about halfway between the cities of Peć and Prizren, it is approximately 100 km inland from the Adriatic Sea and 208 km north-east of Tirana, 145 km north-west of Skopje, 80 kilometres west of the capital Pristina, 435 kilometres south of Belgrade and 263 kilometres east of Podgorica.

History. The city of Gjakova has been populated since the prehistoric era. During the Ottoman period, Gjakova served as a trading center on the route between Shkodër and Istanbul. It was also one of the most developed trade centers at that time in the Balkans with the marketplace being by the Hadum Mosque, built in 1594 by Mimar Sinan, and financed by Hadum Aga.

Gjakova suffered greatly from the Serbian and Montenegrin armies during the First Balkan War. The New York Times reported in 1912, citing Austro-Hungarian sources, that people on the gallows hung on both sides of the road, and that the way to Gjakova became a “gallows alley.” The Montenegrin military police committed much abuse and violence against the non-Orthodox Christian population.

In the Kosovo War, the town suffered great physical destruction, large-scale human losses and human rights abuses. About 75% of the population was expelled by Serbian police. Large areas of the town were destroyed, chiefly through arson and looting but also in the course of localized fighting. Most of the Albanian population returned following the end of the war. In 2001, thousands of new stores were rebuilt as they had been before the war.

In 2011, the resident population was 94,556 (urban 40,827 and rural 53,729. The ethnic groups include Albanians (87,672), Balkan Egyptians (5,117), Roma (738), Ashkali (613), and smaller numbers of Bosniaks (73), Serbs (17), Turks (16), Gorani (13) and others. Based on those who answered, the religious make-up was 77,299 Muslims, 16,296 Roman Catholics, 22 Orthodox Christians, 142 others, and 129 irreligious.

Gjakova has a long tradition of education – the Hadim Aga library was so rich in books that it was said “Who wants to see the Kaaba, let them visit the library of Hadim Aga”. The economy is based primarily on farming and agriculture.

Historical Monuments.

Old Bazaar is the oldest bazaar in Kosovo serving as an Ottoman trading center and heart of the town’s economy and had 1000 businesses in 1900. It suffered damage during the Kosovo War but has since been renovated. The length of its main road is 1 km, with about 500 shops situated along it. The original street was cobbled stone, but the new pavement of tiles is already breaking up.

Hadum Mosque is located in the Old Bazaar. Built in 1594, it was financed by Hadum Aga and belongs to the Sufi order. Square, the 13.5m diameter, 12.6m high dome it is decorated with landscapes, architecture (mosques), cypress trees, floral ornaments geometric figures and quotations from the Qur’an, all beautifully painted.

It has a wonderful graveyard with many tombstones lying against the walls and fence.

Ethnographic Museum. Built in 1830.

Saint Paul and Saint Peter Church. Built in 1703, in 1999, it was destroyed but a new cathedral has been built.

Saint Ndou Church was built in 1882, it was later destroyed and rebuilt in 193.

Clock Tower. 30m high, it was built just after the Hadum Mosque, it was destroyed during the Balkan Wars, and a new clock tower was built of stone with the wooden observation area and the roof covered in lead.

Mirusha waterfalls. These were an adventure to find. Follow Google Maps and turn onto a rough gravel road. I drove about 1.1 km and walked down to the bridge (not usable) and the small river. A lovely rocky gorge is downstream. There was no evidence of a waterfall but a rudimentary track could be seen descending from above. I tried to find a way down, but it was very bushy and I could hear a waterfall. It appears that the best place to park would be at a large clear area with a track descending to the river. I got tired of the adventure and did not follow it down.

Gadime Cave (Marble Cave). Discovered in 1969, this was a very unique cave – I have never seen one like it despite being in a lot of caves. It is formed in limestone, not marble and consists of remarkably similar passages all about the same width and height (1.8-3m high) that form an interconnecting maze. The entire floor is concrete with stalagmites cemented into the floor. Spelioforms are not initially frequent with a few draperies and stalactites, many broken off in the Kosovo War. One drapery could be played like an xylophone. At the end of one passage is an almost joined column, a big based column, several soda straws and something I have never seen, a large area of small crystals on the roof with branches going in all directions. At the end of another is a large mass of stalactites. Another passage narrows and extends for 13 km. The cave has not been well explored.

A NM “Sight” and “Cave”, the highway went north almost to Pristina and then south. Seeing the cave is by guided tour in Albanian, but one fellow translated. €2

Gračanica Monastery. South of Pristina, this lovely church is set in the middle of large lawns all fenced by a 2m stonewall. The portico is glassed in and has good frescoes. Inside there are two massive arched columns, good frescoes on the walls, columns and ceiling, a very high dome and a large gilt cross on top of the simple wood iconostasis. Free

Serbian enclaves in Southern Kosovo. This refers to settlements in Kosovo, outside North Kosovo (“south of the Ibar”) where Serbs form a majority. After the initial outflow after the Kosovo War, the situation of the Kosovo Serb communities has improved. According to the 1991 census in Yugoslavia, there were five municipalities with a Serb majority: Leposavić, Zvečan, Zubin Potok, Štrpce and Novo Brdo.

The remaining municipalities had an Albanian majority, while other significant ethnic minorities (such as Muslims and Romani) did not form majorities in any of the municipalities.

PRISTINA

Ethnographic Museum. Situated in the home of a wealthy Pristina family, it consists of their18th century house, the oldest building in Pristina (downstairs meeting room and kitchen and lovely upstairs living suite and bedroom, both with a bank of windows – used as their “guest house”) and their 19th-century new house presently being renovated. All is enclosed in a courtyard surrounded by high walls. This is a hard place to access as it is surrounded by housing complexes. Outside is the Stone House, a Jewish store, the only remaining building from the old Pristina bizarre. Free

Imperial Mosque (Carska džamija u Prištini) is an Ottoman mosque located near the clock tower. It was built in 1461 by Sultan Mehmet II Fatih. The mosque was declared a Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance in 1990 by the Republic of Serbia. During the Austro-Turkish wars, at the end of the 17th century, it was temporarily turned into a Catholic church. After the Ottomans regained control, in 1690, the bones of Pjetër Bogdani, a prominent pro-Austrian rebel buried here were exhumed and thrown into the street by the Ottoman soldiers.

Kosovo Museum/Archaeological Museum. The archaeology section has few labels, and lots of pots and artifacts from Roman Ulpiana and Venice (including an unusual lead sarcophagus and upstairs weapons, guns, mortars, an old motorcycle, and many uniforms. The gallery was closed. Free

Clock Tower (Sahatkulla). This hexagonal stone tower has a square brick top with clocks on each side, all at different times and not working.

Newborn Sign. In the NM “sights” series, this consists of large block letters sitting in front of a shopping centre. It is painted with graffiti-like images and covered in graffiti signatures.

Heroinat Memorial. Across the street from Newborn, this lovely monument of a large bas-relief woman’s head is made of 20,145 brass medals commemorating the dignity, education, care, courage and endurance of ethnic Albanian women during the 1998-99 Kosovo War – the cruel rape of 20,000 women committed by Serbian forces.

It was unveiled on 12 June 2015, celebrated as Kosovo’s Liberation Day. It depicts an Albanian woman using 20,000 pins. Each pin represents a woman raped during the Kosovo War from 1998-1999. The pins are at different heights, creating a portrait in relief.

Cathedral of Saint Mother Teresa. This huge modern church has a very austere interior with plain white walls, a wood ceiling, stained glass of several saints and a dome with a wooden dove. A wood carving of Mother Theresa is in the south transept.

Christ the Saviour Cathedral. This is an intact ruin – a large brick church with a gold cross on the concrete dome sitting in an unkept grassy field next to the university. It is all locked and not accessible.

Gazimestan. This monument, about 8 km north of Pristina, is a large square stone tower sitting on a platform with six cylinders cut on bias. Built in 1953, it commemorates the 1387 Kosovo War where the Ottomans defeated the Kosovo army and then the control of Kosovo by the Ottoman Empire. There are stairs inside that can be climbed to the top.

This was unusual as it had locked gates, two police and identification had to be presented to enter.

The site was the place where Despot Stefan Lazarević erected a marble pillar with an inscription commemorating the battle. That monument disappeared during the Ottoman period. In 1924 a small monument honouring the Serbian heroes at the battle (Kosovski junaci, “Kosovo heroes”) was erected; it was an obelisk with a cross on top. It had a Cyrillic inscription: “To the fallen heroes for the honourable cross, freedom, and rights of their people – 1389 1912 – [by] thankful descendants, citizens and soldiers of the city of Priština”. During World War II, just after the Yugoslav capitulation, the monument was mined by Albanian fascist troops and destroyed. In the years before the war, a larger monument had been planned and a cornerstone placed near where the present monument is, but the threat of war put it on hold.

Until the end of World War I and the creation of Yugoslavia (1918), there were no conditions or opportunities for large masses to gather at the site. More notable celebrations of Vidovdan (St. Vitus’ day) at Gazimestan have been noticed only since 1919, in 1924 when the obelisk was erected, and finally before the start of the war, five and a half centuries after the battle. In this period an estimated 20,000–100,000 people gathered on Vidovdan at Gazimestan. Participants included not only native Kosovo Serbs, but also Serbs from distant regions, such as the Bay of Kotor, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Old Montenegro, and Skoplje, Zagreb, Belgrade and some places in Vojvodina.

In 1989, on the 600th anniversary, Serbian President Slobodan Milošević held the famous Gazimestan speech at the site. In 1997 the site was declared a cultural heritage of Serbia. In 1999, in the aftermath of the Kosovo War (1998–99) the monumental area was mined. In 2007, a 14-day march from Belgrade to Gazimestan was organized by several patriotic organizations. In 2009, the commemoration brought the biggest crowd since 1999, with several thousand people. In 2010, the Kosovo Police was handed over the task of guarding the monument, which was criticized by the Serbian government. In 2014, President Tomislav Nikolić held a speech at the monument.

The Gazimestan monument was designed by Aleksandar Deroko, in the shape of a medieval tower, and built in 1953 under the authority of SFR Yugoslavia.

— Inscription on the monument of the “Kosovo curse” attributed to Prince Lazar.

This version first appeared in the 1845 folk songs collection of Vuk Karadžić.

Whoever is a Serb and of Serb birth

And of Serb blood and heritage

And comes not to the Battle of Kosovo,

May he never have the progeny his heart desires!

Neither son nor daughter

May nothing grow that his hand sows!

Neither dark wine nor white wheat

And let him be cursed from all ages to all ages!

Free

After seeing North Kosovo, I reentered South Kosovo on my way to Montenegro.

PEĆ (Peja) (pop 49,000)

This city and municipality in the Peć District of Kosovo includes the city of Peć and 95 villages.

Geographically, it is located on the Peć Bistrica, a tributary of the White Drin to the east of the Prokletije Mountains. The Rugova Canyon is one of Europe’s longest and deepest canyons and is about three kilometres from the city of Peć. The city is located some 250 km north of Tirana, Albania, 150 km north-west of Skopje, 85 km west of Pristina and some 280 km east of Podgorica, Montenegro.

In medieval times the city was the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1346. Later in 1899, the Albanian political organization, League of Peja, was established in the city. The patriarchal monastery of Peć is a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the Medieval Monuments in Kosovo.

History. The medieval city was possibly built on the ruins of Siparant(um), a Roman municipium (town or city). Slavs settled the Balkans, heavily depopulated by “barbarians”, in the 6th century. The Byzantine Empire and the First Bulgarian Empire fought for control of the area until it finally fell under full Serbian control. Between 1180 and 1190.

In 1220, Serbian King Stefan Nemanjić donated Peć and several surrounding villages to his newly founded monastery of Žiča. As Žiča was the seat of a Serbian archbishop, Peć came under direct rule of Serbian archbishops and later patriarchs who built their residences and numerous churches in the city starting with the church of Holy Apostles built by archbishop Saint Arsenije I Sremac. After the Žiča monastery was burned by the Cumans (between 1276 and 1292) the seat of the Serbian archbishop was transferred to a more secure location – the Patriarchal Monastery of Peć where it remained until the abolition of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in 1766.

The city became a major religious center of medieval Serbia under the Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan, who made it the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1346. It retained this status until 1766 when the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was abolished. The city and its surrounding area are still revered by adherents of Serbian Orthodoxy; the Patriarchal Monastery of Peć is an easy walk from the city centre.

Peja came under Ottoman rule after its capture in 1455. The city was settled by a large number of Turks, many of whose descendants still live in the area, and took on a distinctly oriental character with narrow streets and Ottoman-style houses. It also gained an Islamic character with the construction of a number of mosques, many of which still remain. One of these is the centrally located Bajrakli Mosque built in the 15th century.

Ottoman rule came to an end in the First Balkan War of 1912–13, when Montenegro took control of the city. Relations between Serbs and Albanians, who were the majority population, were often tense during the 20th century. They came to a head in the Kosovo War of 1999, during which the city suffered heavy damage and mass killings. More than 80 percent of the total 5280 houses in the city were heavily damaged or destroyed. It suffered further damage in violent inter-ethnic unrest in 2004.

Ethnic groups. The vast majority of the inhabitants are Kosovo Albanians. Most Kosovo Serbs live in the village enclaves of Goraždevac, Belo Polje and Ljevoša. There is also a large Bosniak community while significant Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities are in urban and rural areas.

Tourism. Peć is rapidly developing a significant tourist infrastructure with a new Zip Line, and two Via Ferrata, built between 2013 and 2016.

You can find information and maps for the “Trail of Cultural Monuments” at the Tourist Information Office as well as maps and attractions in the Rugova Gorge/Canyon and surrounding mountains. Skiing is available at the Ski Center in Bogë nearby. The peak of the Balkans trail wanders through 3 countries with mountain views and can be supported by local guides and tour companies.

Peja Old Town. Pedestrianized, it does not look very old as most were reconstructed after the Kosovo War but is very attractive with dark wood store fronts, white plaster and terracotta roofs.

Ethnographic Museum (Etno Kuca). In the Tahir Beg, a 17th-century townhouse that is very well preserved, it has exhibits on costumes, jewelry, work implements and other cultural artifacts. €2

Bajrakli Mosque. In the Old Town, this square stone mosque with one huge central dome was undergoing renovation and could not be visited. It was destroyed during WW II and then rebuilt.

Pec Hamam is an Ottoman-era bath.

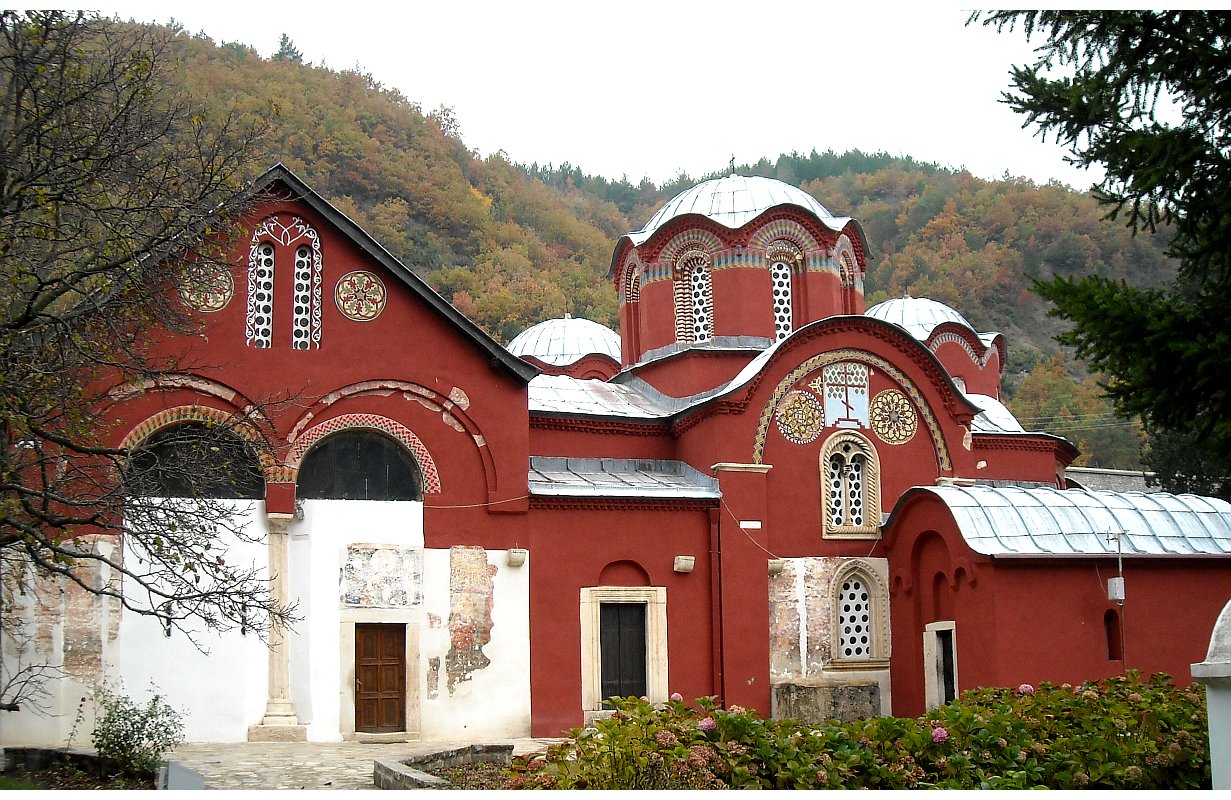

Patriarchate of Peć Monastery is a medieval Serbian Orthodox monastery located near the city of Peć. Built in the 13th century, it became the residence of Serbian Archbishops. It was expanded during the 14th century, and in 1346, when the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was created, the Monastery became the seat of Serbian Patriarchs. The monastery complex consists of several churches, and during medieval and early modern times it was also used as the mausoleum of Serbian archbishops and patriarchs. Since 2006, it has been part of the “Medieval Monuments in Kosovo”, a combined World Heritage Site along with three other monuments of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

The monastery is ecclesiastically administrated by the Eparchy of Raška and Prizren, but it has special (stavropegial) status since it is under the direct jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarch whose title includes Archbishop of Peć. The monastery church is unique in Serbian medieval architecture, with three churches connected as one whole, with a total of four churches.

The monastery complex is located near Peć, in the Metohija region, on the main road connecting Metohija with Montenegro. It is situated by the Peć Bistrica, at the entrance of the Rugova Canyon. A morus nigra tree, 750 years old, is preserved in the monastery yard, planted by Archbishop Sava II between 1263 and 1272.

History. The monastery is located at the edges of the old Roman and Byzantine Siperant. The monastery complex, consisting of four churches, of which three churches connected as one whole, was built in the first third of the 13th century, 1321–24, and 1330–37. It is presumed that the site became a metochion (land owned and governed by a monastery) of the Žiča monastery, the seat of the Serbian Archbishopric at that time, while Archbishop Sava (d. 1235) was still alive. In the first third of the 13th century, Archbishop Arsenije I (s. 1233–63) had the Church of the Holy Apostles built on the north side. That church was decorated on Arsenije’s order in ca. 1250 or ca. 1260. In 1253, Arsenije I moved the Serbian Church seat from Žiča to Peć amid foreign invasion, to a more secure location, closer to the centre of the country. The Serbian Church seat was then shortly returned to Žiča in 1285, before being moved to Peć in 1291, again amid foreign invasion. Archbishop Nikodim I (s. 1321–24) built the Church of St. Demetrius on the north side of the Church of the Holy Apostles, while his successor, Archbishop Danilo II (s. 1324–37) built the Church of the Holy Mother of God Hodegetria and the Church of St. Nicholas on the south side. In front of the three main churches, he then raised a monumental narthex. In the time of Archbishop Joanikije II, around 1345, the hitherto undecorated Church of St. Demetrius was decorated with frescoes. Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan (r. 1331–1355) raised the Serbian Archbishopric to the patriarchal status in 1346, thus creating the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.

During the 14th century, small modifications were made to the Church of the Holy Apostles, so some parts were decorated later. From the 13th to the 15th century, and in the 17th century, the Serbian Archbishops and Serbian Patriarchs were buried in the churches of the Patriarchate. In 1459–63, after the death of Arsenije II, the patriarchate became vacant upon abolishment by the Ottoman Empire but was restored in 1557 during the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent The re-establishment was done under the advice of grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, while some of Bulgarian eparchies were also placed under its jurisdiction. Georgije Mitrofanović (1550–1630) painted new frescoes in the Church of St. Demetrius in 1619–20. In 1673–74 painter Radul painted the Church of St. Nicholas. In the early 18th century, and especially during and after the Austro-Russian–Turkish War (1735–1739), the patriarchate became the target of the Phanariotes and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, whose goal was to place the eparchies of the Serbian Patriarchate under its own jurisdiction. In 1737 the first Greek head of the Serbian Patriarchate was appointed after the intervention of Alexandros Mavrocordatos, who labeled the Serb leadership “untrustworthy”. In the following years, the Phanariotes embarked on policy initiatives that led to the exclusion of Serbs in the succession of the patriarchate, which was eventually abolished in September 1766.

The period of Ottoman rule in the region ended in 1912. At the beginning of the First Balkan War (1912-1913), an army of the Kingdom of Montenegro entered into Peć. By the Treaty of London (1913) the region of Peć was officially awarded to Montenegro and the Monastery of Peć again became an episcopal seat. Bishop Gavrilo Dožić of Peć (future Serbian Patriarch) initiated works on the monastery complex, but those efforts were halted due to the breakout of the First World War (1914) and subsequent Austro-Hungarian occupation of Montenegro, including Peć. War ended in 1918, and Montenegro joined the Kingdom of Serbia and South Slavic provinces of former Austria-Hungary to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians. In 1920, the structural unity of the Serbian Orthodox Church was restored, and the Serbian Patriarchate was renewed, with a traditional primatial seat in the Patriarchal Monastery of Peć. Since then, all Serbian Patriarchs were enthroned in the Monastery. Major reconstruction works in the Monastery were undertaken during 1931 and 1932.

In 1947, the Patriarchate of Peć was added to Serbia’s “Monument of Culture of Exceptional Importance” list, and on 13 July 2006 it was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List as an extension of the Visoki Dečani site which was overall placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger.

Restoration of the complex began in June 2006 and was completed in November 2006. The main aim was to protect the complex from the weather, as well as to repair the inner walls and exterior appearance. Two previously unknown frescoes were uncovered on the north facade of the Church of St. Demetrios, of a Serbian queen and nobleman. In 2008, the church facades were painted red, as Žiča, which led to some reactions. The sites were protected by the Kosovo Force until 2013 when the Kosovo Police took over responsibility.

Mausoleum. The monastery is the greatest mausoleum of Serbian religious dignitaries (most of whom are saints: Arsenije (s. 1233–63), Sava II (s. 1263–71), Jevstatije I (s. 1279–86), Jefrem (s. 1375–79; 1389–92), Spiridon (s. 1380–89) and Joanikije II (s. 1338–54), Maksim I (s. 1655–74).

The three main churches with domes (Holy Apostles, St. Demetrius and Hodegetria) are connected, and linked by a joint monumental narthex. A smaller church, without a dome, is by the side of the Hodegetria Church.

The gift shop was manned by a very talkative nun. 20 nuns reside here. There are orchards, vineyards and agricultural land associated with the monastery. €2

![]()

White Drin Waterfall. About 11 km from the outskirts of Pec, drive past a restaurant and then another 200m down a gravel road and park at another restaurant. Signs are for Dravadc Cave. Walk a short distance to see the falls that drop initially in 3 small cascades and then a large drop into a pool. You can walk down to the bottom or along the side, cross the falls at the very top on a water control/diversion system and continue onto the cave. Apparently, the cave goes completely through the mountain but has never been explored. A dog reputably made the trip. This waterfall is the most powerful in Kosovo at 5 cubic metres/second.

I continued onto Montenegro from here. From the waterfall turn-off, it was about 20 km up a long switchbacking road (that never seemed to end) to the Montenegro border check at the top of the mountains. Snow was beside the road.