Syria – Central and Northeast (Aleppo, Homs, Hama, Idlib, Latakia, Tartus) November 5-7, 2019

Aleppo was our final destination from Damascus. The main expressway (a 385kms drive from Damascus) has been closed for 5 years and is presently controlled by al-Nusra. The route we had to take was a two-lane highway, most without a center line and 580 km. We arrived in Aleppo well after dark at 18:30. There were all sorts of issues at night mandating slower speeds: big trucks, many vehicles without lights, tractors and other slow-moving traffic and motorcycles. We had had an accident after Homs hit a concrete barrier with the right rear of the car – the rim of the tire was significantly scraped and the bumper hanging off. We had to see a body repair place to reattach the bumper. This was a little more excitement than I needed.

The military checkpoints seemed endless. All asked for my passport and most looked in the trunk. As we approached Aleppo, they were in full uniform with helmets.

HOMS

Homs is a city in western Syria, 501m above sea level and is 162 km north of Damascus. Located on the Orontes River, Homs is also the central link between the interior cities and the Mediterranean coast.

Before the Syrian Civil War, Homs was a major industrial centre, and with a population of at least 652,609 people in 2004, it was the third-largest city in Syria after Aleppo to the north and the capital Damascus to the south. Its population reflects Syria’s general religious diversity, composed of Sunni and Alawite Muslims, and Christians. There are a number of historic mosques and churches in the city, and it is close to the Krak des Chevaliers castle, a World Heritage Site.

Starting on 6 May 2011, the city was under siege by the Syrian Army and security forces. The Syrian government claims it is targeting “armed gangs” and “terrorists” in the area. According to the Syrian opposition, Homs has since become a “blighted city,” where authorities regularly block deliveries of medicine, food and fuel to the inhabitants of certain districts. By June, there were near-daily confrontations between protesting residents and Syrian forces. As a result of these circumstances, there have been more deaths in Homs and its vicinity than in other areas of Syria. Homs was the first Syrian city where images of al-Assad and his family were routinely torn down or defaced and the first place where Syrian forces used artillery during the uprising. The Center for Documenting Violations in Syria claims that at least 1,770 people have been killed in Homs since the uprising began.

On 9 December 2015, under a UN-negotiated deal, the remnants of anti-government forces and their families, who had been under siege in the al-Wair district for three years, began to evacuate from the city

During the Syrian Civil War, 30% of the city was destroyed in war due to the Siege of Homs; reconstruction of affected parts of the city is underway with major reconstruction beginning in 2018.

Khalid ibn Al-Walid Mosque. This is a large grey stone mosque with two new limestone minarets and several silver domes. It was closed – the main mosque is relatively undamaged but the grey/white striped courtyard is heavily damaged.

HAMA

Hama is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located 213 km (132 mi) north of Damascus and 46 kilometres (29 mi) north of Homs. With a population of 854,000 (2009 census), Hama is the fourth-largest city in Syria after Damascus, Aleppo and Homs.

HISTORY

Hama grew prosperous during the Ayyubid period, as well as the Mamluk period. It gradually expanded to both banks of the Orontes River, with a new bridge, over thirty different-sized norias (water-wheels), a massive citadel and a special aqueduct that brought drinking water to Hama from the neighbouring town of Salamiyah. Ibn Battuta visited Hama in 1335 and remarked that the Orontes River made the city “pleasant to live in, with its many gardens full of trees and fruits.”

In the 18th century, it was under the governor of Damascus, the Azems, who also ruled other parts of Syria, for the Ottomans. They erected sumptuous residences in Hama, including the Azem Palace and Khan As’ad Pasha. There were 14 caravansaries in the city.

After the end of Ottoman rule in 1918, it was an agricultural area controlled by large estates worked by peasants and dominated by a few magnate families. During the French Mandate, the district of Hama included 114 villages, only four owned outright by local cultivators and the rest owned by landowning elites. Starting in the late 1940s, significant class conflict erupted as agricultural workers sought land reform and better social conditions. Hama was the base of his Arab Socialist Party, which later merged with another socialist party, the Ba’ath. This party’s ascent to power in 1963 signaled the end of power for the landowning elite.

Hama was a stronghold of conservative Sunni Islam and in 1964 and from 1976-1982, Hama was as a major source of opposition to the Ba’ath government. The 1981 and 1982 Hama massacres were put down by the president’s brother, Rifaat al-Assad, with very harsh means. Tanks and artillery shelled the neighbourhoods held by the insurgents indiscriminately, and government forces are alleged to have executed thousands of prisoners and civilian residents after subduing the revolt. The story is suppressed and regarded as highly sensitive in Syria.

The city was one of the main arenas of the Syrian civil war during the 2011 siege of Hama but was left relatively unscathed.

Most of the residents are Sunni Muslims (Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmen) and Hama is the most conservative Sunni Muslim city in Syria.

MAIN SIGHTS

Norias of Hama. Hama’s most famous attractions are these 17 water wheels, dating back to the Byzantine times (and claimed by the locals to originate from 1100 BC). Fed by the Orontes river, they are up to 20 metres (66 ft) in diameter. The largest norias are the al-Mamunye (1453) and the al-Muhammediye (14th century). Originally they were used to route water into aqueducts, which led into the town and the neighbouring agricultural areas and used for watering the gardens. Though historically used for irrigation, the norias exist today as an almost entirely aesthetic traditional show.

Azem Palace. This 18th-century Ottoman governor’s residence holds the museum with its highlight, a precious 4th-century Roman mosaic from the nearby village of Maryamin.

Nur al-Nuri Mosque. Finished in 1163 by Nur ad-Din after the earthquake of 1157, it is noted for its minaret but has not been open for many years since the Great Mosque was built.

The Great Mosque. Destroyed in the 1982 bombardment, it has been rebuilt in its original form. It has elements dating from the ancient and Christian structures existing in the same location. It has two minarets and is preceded by a portico with an elevated treasury.

ALEPPO

Aleppo is the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Syrian governorate. With an official population of 4.6 million in 2010, Aleppo was the largest Syrian city before the Syrian Civil War; however, now Aleppo is probably the second-largest city in Syria after the capital Damascus.

Aleppo is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world; it may have been inhabited since the 6th millennium BC. Such a long history is attributed to its strategic location as a trading center at one end of the Silk Road and midway between the Mediterranean Sea and Mesopotamia. For centuries, Aleppo was the largest city in the Syrian region, and the Ottoman Empire’s third-largest after Constantinople and Cairo.

When the Suez Canal was inaugurated in 1869, much trade was diverted to sea and Aleppo began its slow decline. At the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, Aleppo lost its northern hinterland to modern Turkey, as well as the important Baghdad Railway connecting it to Mosul. In the 1940s, it lost its main access to the sea, Antakya and İskenderun, also to Turkey. Finally, the isolation of Syria in the past few decades further exacerbated the situation. This decline may have helped to preserve the old city of Aleppo, its medieval architecture and traditional heritage. It won the title of the “Islamic Capital of Culture 2006”, and has had a wave of successful restorations of its historic landmarks.

For more history on Aleppo.

Syrian Civil War

The Battle of Aleppo (2012–2016) occurred in the city during the Syrian Civil War, and many parts of the city suffered massive destruction. Affected parts of the city are currently undergoing reconstruction.

Starting in August 2011, some months after protests had begun elsewhere in Syria, anti-government protests were held in several districts of Aleppo, In early 2012, security forces began to be targeted with bombings. In late July 2012, the conflict reached Aleppo in earnest when fighters from the surrounding countryside mounted their first offensive there, apparently trying to capitalize on the momentum gained during the Damascus assault. Since then some of the civil war’s “most devastating bombing and fiercest fighting has taken place” in Aleppo, often in residential areas.

As of spring 2013, the Syrian army has entrenched itself in the western part of Aleppo (government forces were operating from a military base in the southern part of the city) and the armed opposition in the eastern part with a no man’s land between them. One estimate of casualties is 13,500 killed – 1,500 under 5 years of age – and 23,000 injured. Local police stations in the city were a focus of conflict.

As a result of the severe battle, many sections in Al-Madina Souq (part of the Old City of Aleppo World Heritage Site), including parts of the Great Mosque of Aleppo and other medieval buildings in the ancient city, were destroyed and ruined or burnt in late summer 2012 as the armed groups of the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Arab Army fought for control of the city. In March 2013, the Syrian Foreign Ministry claimed that some 1,000 factories in Aleppo had been plundered, and their stolen goods were transferred to Turkey with the full knowledge and facilitation of the Turkish government.

A stalemate that had been in place for four years ended in July 2016, when Syrian government troops closed the last supply line of the armed opposition into Aleppo with the support of Russian airstrikes. The Syrian government’s victory was widely seen as a potential turning point in Syria’s civil war.

On 22 December, the evacuation was completed with the Syrian Army declaring it had taken complete control of the city. Red Cross later confirmed that the evacuation of all civilians and rebels was complete.

When the battle ended, 500,000 refugees and internally displaced persons returned to Aleppo, and hundreds of factories returned to production as electricity supply increased. Many parts of the city that were affected, including the citadel, are undergoing reconstruction. The Aleppo shopping festival took place on 17 November 2017 to promote industry in the city.

By February 2018, Kurdish fighters had shifted to Afrin to help repel the Turkish assault. As a result, the pro-Syrian government forces regained control of the districts previously controlled by them.

We drove through east Aleppo, destroyed with bombed-out buildings skeletons and much reduced to rubble. Rebuilding is actively started with a few stores open. The sounds of construction are everywhere. It is cruel to watch a couple of guys with wheel barrows clearing huge piles of rubble and surprising to see one tiny rebuilt building in a totally destroyed neighborhood. Most of the streets and lanes have been cleared with piles of stone lined up on each side.

We talked to an engineer in charge of repairing the telephone building. He commented that Aleppo had been destroyed 38 times in the past (the last major one was the 1815 earthquake) and it has always been rebuilt. This time would be no different.

ANCIENT CITY of ALEPPO. A World Heritage Site, it received the most damage in Aleppo in the Syrian war. After ISIS did its thing, the al-Nusra Front moved in for 3 years and occupied most of it.

Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo. ISIS destroyed the minaret (they planted a bomb in the bottom but then blamed Assad for dropping bombs), the east side of the mosque was destroyed, the 12th-century wooden minbar was stolen by ISIS, and the courtyard was destroyed.

Before and after photos of Umayyad Mosque

The army guard in front was an eyewitness to the destruction of the minaret and subsequent occupation as he and the Syrian army were outside when it happened. He is 46, his family lives within 200m of the mosque and he is here defending his family. He told us that they were confident about ISIS planting a bomb. Al-Nusra occupied the mosque and east Aleppo for 3 years after ISIS left. Al-Husra stated that they would rape and kill their family.

It was not permitted to visit as it was undergoing full reconstruction. We parked on the street outside, saw the gate with its wonderful maqarnas, the west wall has been rebuilt and a large crane was involved in rebuilding the minaret. The soldier finally agreed to let me have a look inside. I was just able to walk a few metres past the portal into the courtyard. The open area in front of the mosque and the entire large courtyard was covered in 1,600 large blocks of stone, the remnants of the minaret. The first few meters of the minaret had been reconstructed in gleaming white limestone.

Al Vizer Caravanserai. This 17th-century caravanserai was intact but was surrounded by bombed-out buildings. It was once used by wealthy merchants and traders. Two-story, the bottom was shops and the upper arcaded part was hotel rooms. The three windows in the tower entrance were of Christian, Jewish and Moslem design.

The gate with its three windows

Bazaar of Haleb. Once 14 km of covered bazaar with 6,500 shops, the north end was totally destroyed and reduced to rubble and skeletons of walls. But all the rubble had been cleared and we were able to walk around. It was eerie walking through the long lane to the south end of the bazaar. Relatively intact but empty of people and shops, I marvelled at all the high domes over some of the side lanes. Near the end, we came upon one tiny shop

open.

The bazaar before the war

The end of the main lane of the bazaar opens onto the wide esplanade surrounding the citadel. The main hotel of Aleppo was completely flattened with not a wall standing. A few sidewalk cafes were open.

Ar-Rahman Mosque is a contemporary mosque located on King Faisal Street. It was opened in 1994 and features a combined style of the early Umayyad architecture and modern mosques.

It has a large central dome surrounded with 2 high and 4 shorter rectangular minarets. The external walls of the mosque are decorated with stones in the form of traditional Quran pages, inscribed with some verses from the Ar-Rahman sura.

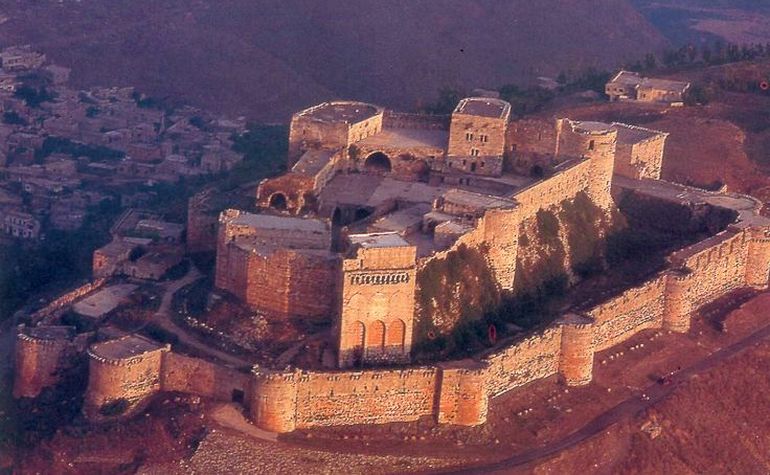

Aleppo Citadel is a large medieval fortified palace in the centre of the old city. It is considered to be one of the oldest and largest castles in the world. Usage of the Citadel hill dates back at least to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. Subsequently, occupied by many civilizations including the Greeks, Byzantines, Ayyubids and Mamluks, the majority of the construction as it stands today is thought to originate from the Ayyubid period. An extensive conservation work took place in the 2000s by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Dominating the city, the Citadel is part of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.

The Citadel in its present form today, sits on an elliptical mound with a base 450m long and 325m wide. The top is 285m by 160m with the height of this slanting foundation of 50 metres (160 feet). In the past, the entire mound was covered with large blocks of gleaming limestone, some of which still remain today. The mound is surrounded by a 22-metre-deep and 30-metre-wide moat, dating from the 12th century. Notable is the 16th century fortified gateway, accessible though an arched bridge.

The enormous stone bridge constructed by Sultan Ghazi over the moat led to an imposing bent entrance complex. Would-be assailants to the castle would have to take over five turns up a vaulted entrance ramp, over which were machicolations for pouring hot liquids on attackers from the mezzanine above. Secret passageways wind through the complex, and the main passages are decorated with figurative reliefs. The Ayyubid block is topped by the Mamluk “Throne Hall”, a hall where Mamluk sultans entertained large audiences and held official functions.

Architecturally, the entrance portal has muqarnas, or honeycomb vaulting, and a courtyard on the four-iwan system, with tiling. Laid out in traditional medieval Islamic style, the palace hammam has three sections.

Several wells penetrate down to 125 m (410 ft) below the surface of the crown. Underground passageways connect to the advance towers and possibly under the moat to the city.Particularly interesting in the interior are the Weapons’ Hall, the Byzantine Hall and the Throne Hall, with a restored decorated ceiling. A 30-year old amphitheater is often used for musical concerts or cultural events.

In August 2012, during the Battle of Aleppo, the external gate was damaged by shelling and in 2015, a bomb was exploded in a tunnel under one of the outer walls causing further damage to the citadel. During the conflict, the Syrian Army used the Citadel as a military base, and according to the opposition fighters, with the walls acting as cover while shelling surrounding areas and ancient arrow slits in walls being used by snipers to target rebels.

JDAIDEH NEIGHBORHOOD

The east part of the Christian area was likewise totally destroyed. Once full of hotels, gold and silver stores and restaurants, we had a walk through the ruins. Aleppo’s best boutique Hotel was completely flattened. We walked through lanes lined with ruins to reach the New Bazaar (shopping street), totally untouched and then walked back through the south part of the neighborhood.

Maronite Cathedral of Aleppo (1873-1923). The wood roof and some inside walls were destroyed and the dome had several holes. But all had been totally repared, we entered despite being under construction. The wood roof had been totally reconstructed, holes in the dome repaired, the entire back wall of the apse rebuilt. We sat and talked to Mohammud, the Muslim architect from the north of Syria working here for free and drank tea.

Cathedral before the war

And after – all of this has been repaired

40 Martyrs Armenian Cathedral. Also rebuilt after minor damage, the church is 5-naved with 4 rows of stone columns and rough stone ceilings formed into many domes. An original chapel dates to the 9th century but the main church is 19th. The church contains several wonderful paintings, one of the Last Judgement and one of St George slaying the dragon.

The Church of Saint Simeon Stylites. A part was destroyed by ISIS. It is being used by the army to teach women to be snipers. Al-Nusra is still in the area and it cannot be visited.

Day 5 Homs and Crac de Chevalier

We saw the inside of the Aleppo Citadel in the morning and then started the long 350kms drive to Homs and Crac de Chevalier.

At the Aleppo Citadel, from the entire west side of Aleppo, we head explosions and gunfire.

North of Homs we encountered a huge convoy of Syrian military – 23 transport buses full of troops and about 15 Toyoto trucks equipped with large machine guns. At the next military checkpoint, I asked where the army was going. He replied to Raqqa. Raqqa has been in Syrian army control for some time but has been looked after by the Kurdish army. The Syrian Army was going there to relieve them (peacefully) in order for them to be able to better deal with Turkey aggression in the north.

I drove the car for about an hour – considerably safer than my guide who tended to hug the center line playing “chicken” with all the big trucks and often passed unsafely.

We saw the castle at the end of the day in good

KRAK DES CHEVALIERS

(Crac des Chevaliers, literally “Fortress of the Kurds”), and formerly Crac de l’Ospital, is a Crusader castle in Syria and one of the most important preserved medieval castles in the world. The site was first inhabited in the 11th century by a settlement of Kurdish troops garrisoned there by the Mirdasids. As a result, it was known as Hisn al-Akrad, meaning the “Fortress of the Kurds”. In 1142, it was given by Raymond II, Count of Tripoli, to the order of the Knights Hospitaller and remained in their possession until it fell in 1271. It became known as Crac de l’Ospital; the name Krak des Chevaliers was coined in the 19th century.

The Hospitallers began rebuilding the castle in the 1140s and were finished by 1170 when an earthquake damaged the castle. The order controlled a number of castles along the border of the County of Tripoli, a state founded after the First Crusade. Krak des Chevaliers was among the most important, and acted as a center of administration as well as a military base. After a second phase of building was undertaken in the 13th century, Krak des Chevaliers became a concentric castle. This phase created the outer wall and gave the castle its current appearance. The first half of the century has been described as Krak des Chevaliers’ “golden age”. At its peak, Krak des Chevaliers housed a garrison of around 2,000. Such a large garrison allowed the Hospitallers to exact tribute from a wide area. From the 1250s the fortunes of the Knights Hospitaller took a turn for the worse and in 1271 Mamluk Sultan Baibars captured Krak des Chevaliers after a siege lasting 36 days, supposedly by way of a forged letter purportedly from the Hospitallers’ Grand Master that caused the Knights to surrender.

Renewed interest in Crusader castles in the 19th century led to the investigation of Krak des Chevaliers, and architectural plans were drawn up. In the late 19th or early 20th century a settlement had been created within the castle, causing damage to its fabric. The 500 inhabitants were moved in 1933 and the castle was given over to the French Alawite State, which carried out a program of clearing and restoration. When Syria declared independence in 1946, it assumed control. Krak des Chevaliers is located approximately 40kms west of the city of Homs, close to the border of Lebanon. Since 2006, the castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din have been recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.

It was partially damaged in the Syrian civil war from shelling and recaptured by the Syrian government forces in 2014. Since then, reconstruction and conservation work on the site had begun.

Today, a village called al-Husn exists around the castle and had a population of nearly 9,000. But it was almost completely destroyed in the war – only a few citizens have returned.

Before the war, Krac des Chevaliers received 5,000 visitors per day at the height of the tourist season. When I visited, I had it all to myself.

For more detail on Krac des Chevaliers, see Syria – World Heritage Sites

TARTUS (pop 115,769 2004)

Tartus is a city on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. It is the second largest port city in Syria (after Latakia). In the summer it is a vacation spot for many Syrians with many vacation compounds and resorts. The port holds a small Russian naval facility. The city occupies most of the coastal plain, surrounded to the east by Syrian Coastal Mountain Range composed mainly of limestone and, in certain places around the town of Souda, basalt. Arwad, the only inhabited island on the Syrian coast, is located a few kilometers off the shore of Tartus.

Climate. Tartus has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa) with mild, wet winters, hot and dry summers, and short transition periods in April and October. The hills to the east of the city create a cooler climate with even higher rainfall. Tartus is known for its relatively mild weather and high precipitation compared to inland Syria. Humidity in the summer can reach 0%.

HISTORY

The History of Tartus goes back to the 2nd millennium BC when it was founded as a Phoenician colony of Aradus. The colony was known as Antaradus (from Greek “Anti-Arados → Antarados”, Anti-Aradus, meaning “The town facing Arwad”). Not much remains of the Phoenician Antaradus, the mainland settlement that was linked to the more important and larger settlements of Aradus, off the shore of Tartus, and the nearby site of Amrit.

Greco-Roman and Byzantine. The city was called Antaradus in Latin. At the time of the Crusades, Antaradus, by then called Tartus or Tortosa, was a Latin Church diocese. It was united to the see of Famagosta in Cyprus in 1295.

No longer a residential bishopric, Antaradus is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see. The city was favored by Constantine for its devotion to the cult of the Virgin Mary. The first chapel to be dedicated to the Virgin is said to have been built here in the 3rd century.[citation needed]

Islamic. Muslim armies conquered Tartus under the leadership of Ubada ibn as-Samit in 636.

Crusades. The Crusaders called the city Antartus, and also Tortosa, first captured by Raymond of Saint-Gilles. In 1123 the Crusaders built the semi-fortified Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa over a Byzantine church that was popular with pilgrims. The Cathedral itself was used as a mosque after the Muslim reconquest of the city, then as a barracks by the Ottomans. It was renovated under the French and is now the city museum, containing antiquities recovered from Amrit and many other sites in the region. Nur ad-Din Zangi retrieved Tartus from the Crusaders for a brief time before he lost it again.

In 1152, Tortosa was handed to the Knights Templar, who used it as a military headquarters. They engaged in some major building projects, constructing a castle with a large chapel and an elaborate keep, surrounded by thick double concentric walls. The Templars’ mission was to protect the city and surrounding lands, some of which had been occupied by Christian settlers, from Muslim attack. The city of Tortosa was recaptured by Saladin in 1188, and the main Templar headquarters relocated to Cyprus. However, in Tortosa, some Templars were able to retreat into the keep, which they continued to use as a base for the next 100 years. They steadily added to its fortifications until it also fell, in 1291. Tortosa was the last outpost of the Templars on the Syrian mainland, after which they retreated to a garrison on the nearby island of Arwad, which they held for another decade.

Civil war. On May 23, 2016, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant claimed responsibility for three suicide bombings at a bus station in Tartus, which had remained largely unaffected since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011. Purportedly targeting Alawite gatherings, the bombs killed 48 people. In Jableh, similarly insulated, another four bombers killed over a hundred people.

Economy, transportation and navy

Tartus is an important trade center in Syria and has one of the two main ports of the country on the Mediterranean. The city port is experiencing major expansion as a lot of Iraqi imports come through the port of Tartus to aid reconstruction efforts in Iraq.

Tartus is a destination for tourists. The city has sandy beaches, several resorts and the Antaradus and Porto waterfront development. The Chemins de Fer Syriens operated railway network connects Tartus to major cities in Syria, although only the Latakia-Tartus passenger connection is in service.

Russian naval base: Tartus hosts a Soviet-era naval supply and maintenance base, under a 1971 agreement with Syria, which is still staffed by Russian naval personnel. Tartus is the last Russian military base outside the former Soviet Union, and its only Mediterranean fueling spot, sparing Russia’s warships the trip back to their Black Sea bases through straits in Turkey, a NATO member.

MAIN SITES

Amrit of Tartus Phoenician Temple (Ma’abed), cella at the center of the court,

Arwad island and castle.

The ancient cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa, now used as the city museum.

The outlying town of Al Hamidiyah just south of Tartus is notable for having a Greek-speaking population of about 3,000 who are the descendants of Ottoman Greek Muslims from the island of Crete but usually confusingly referred to as Cretan Turks. Their ancestors moved there in the late 19th century as refugees from Crete after the Kingdom of Greece acquired the island from the Ottoman Empire following the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. Since the start of the Iraqi War, a few thousands Iraqi nationals now reside in Tartus.

Amrit. This was a large 5th to 6th century Phoenician city near the shore of the sea. The only real thing left is the ruins of a hippodrome and the Temple of Melkert. Built on a natural spring, the limestone walls were excavated to form a square sunken water temple. The cut out blocks were used to build the square temple in the middle and erect the 2.5m columns surrounding it. The columns at one time had a capital around its entire perimeter. The building is quite intact with lovely stepped designs and the basin still filled with water.

Citadel of Tartus. The historic centre of Tartus consists of more recent buildings built on and inside the walls of the Crusader-era Templar fortress, whose moat still separates this old town from the modern city on its northern and eastern sides. Once a large Crusader Castle on the water, it is now riven with streets and mainly used as a residence. Laundry hangs out the windows.

This is a tentative WHS – la cité-citadelle des Croisés (08/06/1999)

After Tartus, we drove to Latakia and stayed in the Vitro Hotel.

LATAKIA (384,000 in 2004, now 1.5million with all the immigration from the rest of Syria)

Latakia is the principal port city of Syria. Its population greatly increased as a result of the ongoing Syrian Civil War due to the influx of refugees from rebel and terrorist held areas. It is the 4th-largest city in Syria after Aleppo, Damascus and Homs, and it borders Tartus to the south, Hama to the east, and Idlib to the north while Cape Apostolos Andreas, the most north-eastern tip of Cyprus is about 109 km away.

Although the site has been inhabited since the 2nd millennium BC, the city was founded in the 4th century BC under the rule of the Seleucid empire. Latakia was subsequently ruled by the Romans, then the Ummayads and Abbasids in the 8th–10th centuries of the Christian era. Under their rule, the Byzantines frequently attacked the city, periodically recapturing it before losing it again to the Arabs, particularly the Fatimids. Afterward, Latakia was ruled successively by the Seljuk Turks, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and the Ottomans. Following World War I, Latakia was assigned to the French mandate of Syria, in which it served as the capital of the autonomous territory of the Alawites. This autonomous territory became the Alawite State in 1922, proclaiming its independence a number of times until reintegrating into Syria in 1944.

Geography. Latakia is located 348kms north-west of Damascus, 186kms SW of Aleppo, 148kms NW of Homs, and 90kms north of Tartus, bordering Turkey to the north.

Demographics.

Latakia was historically a Sunni city, however the Alawatization process under Hafez al Asaad led to many Alawites moving from the rural hinterland into the city. In 2010 Latakia City was 50% Alawite, 40% Sunni and 10% Christian, with the rural hinterland an Alawite majority of roughly 70%, with Christians 14%, Sunni Muslims 12%, and Ismailis 2%. The city serves as the capital of the Alawite population and is a major cultural center for the religion.

Within the city boundaries is the “unofficial” Latakia camp, established in 1956, which has a population of 6,354 Palestinian refugees, mostly from Jaffa and the Galilee.

Economy. The Port of Latakia is the main seaport in Syria established in 1950.

For more detail, go to Latakia.

Day 8 Ugarit, Saladin Castle, drive to Homs

UGARIT (Tell Shamra). Tentative WHS (08/06/1999)

The kingdom of Ugrarit flourished in the second millennium on the Mediterranean coast. The excavations began in 1929 with the fortuitous discovery of a tomb and subsequently the capital, temples, the remains of a fortification, a vast royal palace and many houses. However, only 1/6 of the site has been excavated. Ugrarit added significant knowledge of urbanism and civilization of a Levant city at the end of the Bronze Age with exceptional works of art. The city was definitivly destroyed in the first years of the 12th century BC by the invasion of the Philistines or “Peoples of the sea”. Archival tablets and documents in several languages show the presence of the first alphabet.

Economy. The wealth of the kingdom came from agriculture (vineyards, olive trees, cereals, livestock, forest), craftsmanship of a mastery never equaled before (metal figurines, tools and ivory tiling workshops) and especially commercial activity: very active Mediterranean trade with the Aegean and Crete, Cyprus, and all the coastal regions of the Levant: Arwad, Byblos, Sidon, Tyr and Egypt. Ugrarit was the intermediary between the Mediterranean, Central Syria and Mesopotamia.

At the beginning of the Bronze Age, the city was surrounded by a powerful rampart of which only part remains, that protecting the royal palace on the western side of the city. The royal zone had its own fortified entrance on the west passed as you access the site. The portal is perfectly preserved – a large oval capped by a huge rock with an inclined stair and two acute angles for defense.

The main urban traffic lane has a width of 4m and was guarded by several gates with massive doors and two unusual “spy holes”. much less than ordinary streets (between 0, 90 m and 2,50 m).

The Royal Palace of the Late Bronze Age, rebuilt several times during the 14th and 12th centuries, covered one hectare. Its splendor was much the admired by its contemporaries. Despite the destruction caused by the fire of the 12th century BC, the pillaging of stones and three thousand years of erosion ruins remain spectacular, with stonewalls preserved in places up to the first floor.

Nearly a hundred courtyards and covered rooms have been recognized at ground level, but to this must be added all the space built in stories, the presence of many stairs attests the existence. The layout of the plan and the nature of the archaeological and archival documents found in the different parts of the palace, show a division between areas reserved for the royal function – with a throne room – and the administration, and private parties and a set reserved for the funeral cult of the royal family and containing beautiful vaults.

Acropolis. At the top of the city-acropolis were the Temples where steles made it possible to identify the deities to whom these monuments were dedicated.

The houses vary in shape and size but characteristically had an entrance vestibule leading to the courtyard and giving access to the staircase; separate house in two autonomous areas each with its entrance on the street and interconnected internally. Privacy was protected by narrow streets with no regular route, the end result of several centuries during which it was rebuilt several times.

Two of the most amazing remnants are in the north end of the site. A huge, 1m high stone jar is perfectly carved.

The tomb of an aristocrat was spectacular – still completely intact, it has perfect stone work in its entrance, walls and perfect vaulting. All the perfectly cut stones are in rows of 7 including the perfect keystone layer at the centre of the vault. The stones on the corners often are shaped to extend past the corner.

Alphabet. What has most contributed Ugarit’s fame is the discovery of some tablets written in the local language of Akkadian and Ugaritian, using thirty signs, a new system of revolutionary writing that is the first alphabet.

These tablets date over about two centuries, the oldest witness of a true literature. The fall and disappearance of the city of Ugarit marked the end of this uniform alphabet. But the invention itself, the principle of alphabetic writing has survived the upheavals that affected the entire coast at the beginning of the 13th century BC.

Between the temples stood constructions including the “house of the high priest” who delivered the most important written documents of the history of the site: the series of tablets which bear the mythological story cycle of Baal which have made the fame of Ugrarit, plus many Bronze tools bearing dedications in Ugaritic that allowed the decipherment of this language in 1930.

Around the year 1000 BC In Byblos, an inscription engraved on a sarcophagus attests the existence of the Phoenician alphabet at that time. Between the 10th and the 6th century BC The alphabet was also borrowed by the Greeks who are at the origin of all the European tradition, both Latin and Cyrillic, while the Aramaic alphabet gave birth to all the Semitic alphabets currently in existence. use, Arabic, Syriac or Hebrew. The alphabet has spread throughout the Mediterranean and throughout the Middle East.

I was very impressed by this site: the separate entrance to the Royal Palace, 1-2m high base layer of the limestone walls are of perfectly cut blocks, 3 streets, the stone jar and the wonderful tomb with perfectly cut blocks and vaulting.

SALADIN CASTLE (Citadel of Salah Ed-Din, Qal’at Salah El-Din. The traditional name of the site is Ṣahyūn, the Arabic equivalent of Zion)

About 25kms NE of Latakia, this was built on a 700m long triangular rock promontory protected on the south and north by deep gorges. It guarded the route between Latakia and the city of Antioch. The first structure was originally Phoenician from the 4th century BC, the remnant of those walls remain in the centre of the present castle. In the 970s, Byzantines built walls on the west extending to the point of the triangle plus a wall on the wide east side. In 1108, the Crusaders took control. They were from the Principality of Antioch, one of the four Crusader states established after the First Crusade. The lords of Sahyun were among the most powerful in Antioch. The fortress was notable as being one of the few which were not entrusted to the major military orders of the Hospitaller and the Templars. The Crusaders built the structure that exists today.

The most amazing construction was a 30m deep, 158m long and 14-20m wide rock cut made to completely isolate the castle from the plateau to the east. A lonely 27m high rock pinnacle was left in the middle of the cut with a 5m high stone column on top to support the wood drawbridge, the only access to the castle. The access road to the castle passes through the rock cut and a stairway was constructed in the 1970s to now give access to the castle.

Stone from the rock cut were used to construct the present castle built on the edge of the cliff faces. They are all perfectly cut with a centre bulge to protect the cement bonding the stones. Massive round towers on the corners square towers on the walls and a keep with 5m thick walls completed the structure.

The present entrance on the south enters one of the square towers. A 22-step staircase fashioned from stones embedded in that tower is not supported on its outside edge.

Cross through the centre of the castle passing the Phoenecian and Byzantine structures to walk out onto the entrance to the drawbridge for views across the cut to where there once was a village. Then climb up into the massive square keep on the east side. The vaulted roofs are supported by a huge 2m square column in the centre. Two sets of stairs climb up perfectly vaulted wells to the top of the tower for amazing views down to the rock cut and canyons surrounding the promontory.

The citadel was made a World Heritage Site along with Krak des Chevaliers, in 2006.

It was then a 220km drive from the castle to Homs, mostly on 4-lane expressway. We passed a gigantic statue of the elder Assad on a small hill. Near Homs we passed a highway sign “LONDON, CAPE TOWN – Adventure Road” dating from the Rally London Cape Town, an adventure race involving as many as 120 antique cars that was last held in 2006.

We drove through large bombed out areas, but the bottom stories often contain open shops.

We stayed in the New Basnan Hotel in Homs. This hotel is the only non-5 Star hotel in Homs. The UN stays at the 5 Star. It is 2 Star and easily the least splashy hotel I have been in for the last month since traveling through Iran, Turkmenistan and now Syria – tiny, single bed, ugly bro In fact, it is the least splashy hotel room I have ever stayed in, including the single bed. But it has things not available before especially in Syria – hot water, coffee, sugar, powdered milk, a clock, plate and utensils, BBC on the TV, needles and thread, a very convenient chair with power nearby. In this mostly Sunni city, it even has a prayer rug (I thought it may be the bathroom mat!). What more could you want? You are mainly sleeping anyway.