Greece – Dodecanese Islands (Rhodes, Kos, Patmos) December 21, 2019

I took the ferry from Marmaris, Turkey to Rhodes for the day, leaving at 09:45 and returning at 15:00, cost €44, company SeaDreams, parking TL30. I had wanted to go to Patmos but there were no vehicle spaces remaining when I booked and would have had to spend 3 days in Rhodes over Christmas with no vehicle.

I arrived at, walked to the Medieval City of Rhodes and saw the Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes and the Modern Greek Art Museum.

RHODES

MEDIEVAL CITY OF RHODES World Heritage Site (1988)

The Order of St John of Jerusalem lost their last stronghold in Palestine, in Acre, in 1291. The military/hospital order founded during the Crusades survived in the eastern Mediterranean area when they then occupied Rhodes, the largest island of the Dodecanese, from 1309 to 1523 and set about transforming the city into fortified city characterised by an obsessive fear of siege and able to withstand sieges – as terrible as those led by the Sultan of Egypt in 1444 and Mehmet II in 1480. Rhodes finally fell in 1522 after a six-month siege carried out by Suleyman II. It subsequently came under Turkish and Italian rule from 1912-45.

With the Palace of the Grand Masters, the Great Hospital and the Street of the Knights, the Upper Town is one of the most beautiful urban ensembles of the Gothic period. In the Lower Town, Gothic architecture coexists with mosques, public baths and other buildings dating from the Ottoman period.

It is located within a 4 km-long wall. It is divided with the high town to the north and the lower town south-southwest. Originally separated from the lower town by a fortified wall, the high town was entirely built by the Knights. The Order was organized into seven “tongues”, each having its own seat, or “inn”. The inns of the tongues of Italy, France, Spain and Provence lined the principal east-west axis, the famous Street of the Knights, on both sides, one of the finest testimonies to Gothic urbanism. To the north, close to the site of the Knights’ first hospice, stands the Inn of Auvergne, whose facade bears the arms of Guy de Blanchefort, Grand Master from 1512 to 1513. The original hospice was replaced in the 15th century by the Great Hospital, built between 1440 and 1489, on the south side of the Street of the Knights.

The lower town has almost as many monuments as the high town. In 1522, with a population of 5000, it had many churches, some of Byzantine construction. Throughout the years, the number of palaces and charitable foundations multiplied in the south-southeast area: the Court of Commerce, the Archbishop’s Palace, the Hospice of St. Catherine, and others.

Its history and development up to 1912 has resulted in the addition of valuable Islamic monuments, such as mosques, baths and houses. After 1523, most churches were converted into Islamic mosques, like the Mosque of Soliman, Kavakli Mestchiti, Demirli Djami, Peial ed Din Djami, Abdul Djelil Djami, Dolapli Mestchiti.

A “Frankish” town. the medieval city was long considered to be impregnable, exerting an influence throughout the eastern Mediterranean basin at the end of the Middle Ages. The ramparts of the medieval city, partially erected on the foundations of the Byzantine enclosure, were constantly maintained and remodeled between the 14th and 16th centuries under the Grand Masters. Artillery firing posts were the final features to be added. At the beginning of the 16th century, in the section of the Amboise Gate, which was built on the northwest angle in 1512, the curtain wall was 12 m thick with a 4 m-high parapet pierced with gun holes. The fortifications of Rhodes exerted an influence throughout the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the Middle Ages.

Rhodes is one of the most beautiful urban ensembles of the medieval Gothic period. The fact that this medieval city is located on an island in the Aegean Sea, that it was on the site of an ancient Greek city, and that it commands a port formerly embellished by the Colossus erected by Chares of Lindos, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, only adds to its interest. Finally, the chain of history was not broken in 1523 but rather continued up to 1912 with the additions of valuable Islamic monuments.

With its Frankish and Ottoman buildings the old town of Rhodes is an important ensemble of traditional human settlement, characterized by successive and complex acculturation. The alterations to the fortification walls and the monuments within the city during the Ottoman period did not harm at all the character of the historical settlement, and are unique and integral evidence of historic layering. The Italian occupation after 1912 left a strong imprint on the urban landscape of Rhodes, with reconstructions of some of the major buildings and are considered a permanent integral part of the urban history of Rhodes. Rhodes remains a living city.

I walked through a large part of the medieval city inside the walls through tiny cobbled lanes with buttressed walls. It is a mixture of modern and stone buildings, and ruins. There are 21 churches, most ruins and 8 mosques.

The walls are completely intact as they were during the Turkish occupation in 1522. Built by the Knights in the 14th century, they have imposing towers, bridges, gates and moats. In some sections there are three sets of walls.

Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes. After a siege by the Ottomans in 1480 and an earthquake in 1481, the original palace was rebuilt in a late Gothic/Renaissance style. The successful second siege by the Ottomans in 1523 destroyed all the eastern residences. All the churches became mosques and the palace was turned into a penitentiary, the hospital into a soldier’s camp. The palace was reduced to a ruin with only the ground floor partially intact. During the Italian period (1912-45), it was completely reinstated in western medieval style as a palace for Mussolini.

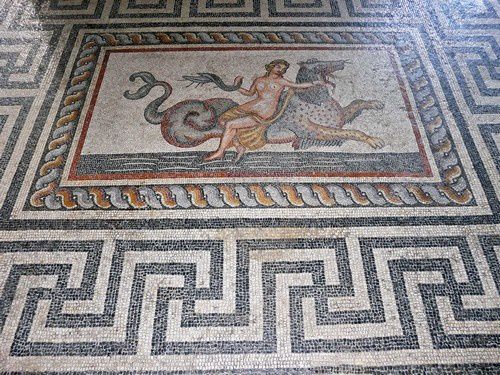

The most stunning part of the renovation were the 27 mosaic floors relocated form Kos civic buildings and 5 basilica churches in 1937-40. Covering most of the second floor, all are completely intact and many contain opus sectile (marble inlays). One room exhibits the intricate drawings of the floors by Hermes Balducci (1904-38).

The palace is a gorgeous reconstruction with wood-beamed ceilings, furniture, several chests, fireplaces, porcelain exhibits and polychromes. €4

Archaeological Museum of Rhodes. Housed in the Gothic hospital of the Knights, it exhibits the art of Rhodes and its surrounding islands from the prehistoric to the early Christian period and that of the Knights. €3

Modern Greek Art Museum. Within the medieval walls, it is on the second story of the Art Museum of Rhodes. €3

I then walked to the northern tip of Rhodes. There is nothing of value except if one wants to shop. The tip is a dark sand/small stone beach. I then continued along the shore. In the harbor is the detached Fortress of St Nicholas, built between 1464 and 67—round with a large central keep. The shore has many sculptures and five ancient round windmills with red conical roofs.

COLOSSUS of RHODES

The Colossus of Rhodes was a gigantic 33-metre-high statue of the sun god Helios that stood by the city’s harbour from c. 280 BCE, one of the most important trading ports in the ancient Mediterranean. Made by the local sculptor Chares using bronze, the statue soon appeared on contemporary travel writers’ lists of must-see sights and was thus known as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Sadly, the giant Helios did not last long. Toppled by an earthquake in 228 or 226 BCE, its massive broken pieces cluttered the docks of Rhodes for a millennium before being melted down as scrap in the mid-7th century CE.

Helios & Rhodes. Helios was the god of the Sun, offspring of the Titans Hyperion and Theia. Not specifically the subject of a widespread cult across Greece,, Plato informs us in his Symposium and other works that many people, including Socrates, would greet the Sun and offer prayers each day. One place Helios was particularly worshipped was at Rhodes, the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece in the eastern Mediterranean. There he was the most important deity, their patron god, and honoured by the Halieia festival, the highlight of the island’s religious calendar and a Pan-Hellenic games much like the ancient Olympic Games. Indeed, in the island’s founding mythology, its very name derives from the nymph Rhodos, who bore seven sons to Helios. In the Hellenistic period (the 4th to 1st century BCE), Helios and the god Apollo would become practically synonymous.

The city of Rhodes, with its five harbours, was ideally placed on the island of the same name to prosper from trade during the Hellenistic domination of the Mediterranean under Alexander the Great’s successors, especially when more and more cities were established in the East. The island’s wealth and strategic position on trade routes did not go unnoticed by ambitious foreign rulers. Antigonus I (c. 382 – 301 BCE), one of Alexander’s successors who controlled Macedon and northern Greece, was one such ruler, and he sent his son Demetrius I of Macedon (c. 336 – c. 282 BCE) to attack Rhodes in 305-4 BCE. The island’s recent alliance with Antigonus’ rival Ptolemy I (c. 366 – 282 BCE) in Egypt was another reason to attack Rhodes and neutralize its powerful naval fleet.

After a 12-month siege, the Rhodians and their formidable fortifications stood firm, and Demetrius negotiated a truce and abandoned the blockade. The Macedonian prince gained his nickname “the Besieger of Cities” but not much else. Demetrius left behind so much siege engine material, including one 36.5 metres (120 ft) high tower, that the Rhodians were able to sell it off for a handsome profit. The polis or city-state already had plenty of money from its lucrative control of trade and there seemed no better way to spend this new windfall than on a massive statue in honour of their patron god, a move which celebrated the island’s hard-won freedom and which might perhaps perpetuate the good times the island was enjoying in the 4th century BCE.

The Colossus. The man commissioned with the Herculean task of sculpting the giant Helios was Chares of Lindus (a city on Rhodes). The project would not be finished until c. 280 BCE, and as the 1st-century CE Roman writer Pliny the Elder noted, it cost 300 talents and took at least 12 years to complete the bronze figure, which stood some 70 cubits or 33 metres (108 ft) high. It is likely that the bronze outer shell, presumably applied in sheets and assembled on site, was supported by internal struts made of iron, and certain pieces were weighted with stones to increase the figure’s stability.

Although Helios was usually envisaged and represented in art as a charioteer with a sun-beamed halo riding across the sky and dragging the sun behind him, the Rhodians perhaps went for a more statuesque representation for their colossal figure. Unlike many other super-famous sculptures from antiquity, though, there are no surviving representations or scale models of the Colossus in other ancient art forms to help reconstruct in detail what the Colossus may have looked like. If the depictions of Helios on the Hellenistic silver coins of Rhodes are anything to go by, we can speculate that the statue may have had the god with his usual crown of pointed sunbeams. A relief of Helios on a stone from a temple at Rhodes has the god shading his eyes with one hand but whether this was replicating the stance of the Colossus or not is unknown. Similarly, the popular belief that the statue was holding a torch like the US Statue of Liberty is based on the misreading of a later Rhodian poem, thus confusing a real light with the metaphor of one in the statue’s original base inscription.

The base of the statue carried the following inscription, preserved in the ancient anthology of poetry, the Palatine Anthology (VI.171): To you, Helios, yes to you the people of Dorian Rhodes raised this colossus high up to the heaven, after they had calmed the bronze wave of war, and crowned their country with spoils won from the enemy. Not only over the sea but also on land they set up the bright light of unfettered freedom. (quoted in Romer, 40)

The exact location of the statue is not known as no ancient writer bothered to say, but the eastern side of the harbour is the most likely spot. Certainly, later Roman statues at ports like Ostia had statues near their harbours that may have mimicked the great example at Rhodes. The medieval fortress of Saint Nicholas, itself built on the site of an earlier church dedicated to the same saint, still stands on the Mandraki harbour mole. Pagan monument sites were often reused by Christians as a potent symbol of the new order, and there was a tradition in medieval times that the broken feet of the Colossus once stood here. More concrete evidence, well, actually sandstone evidence, is a large circle of cut blocks that could have served as the foundation for the statue’s base. In addition, there are fine, slightly curved marble blocks randomly used in the fortresses’ walls that date to the 3rd century BCE, as well as odd-shaped stones which may have been part of the weights used in the statue’s interior.

A second possible location is in the high city centre, where there was a sanctuary to Helios if inscriptions and suitable pieces of masonry can be relied upon as testimony. The Greeks typically sited their statues of deities either in or next to the sanctuary that was dedicated to them but, despite extensive archaeological investigations, no traces of the statue have been found here. Finally, a tradition built up, perpetuated by oft-reprinted medieval drawings, that the giant figure stood astride the entrance to the military harbour, but the dimensions required for a figure in such a pose which allowed ships to pass underneath make it a highly unlikely possibility and contrary to all ancient sources on the statue’s dimensions.

All that can be said for sure about the Colossus of Rhodes, then, is that it was massive and that quality was a particular feature of Hellenistic sculpture and art in general.

Like the Hellenistic Age itself, the statue’s life was a brief one. Too big for its own good, the statue would, like the empire of Alexander, be shattered into pieces and picked over by subsequent cultures. If ever an art piece reflected a culture, it was the Colossus of Rhodes and its unfortunate fate.

The Seven Wonders. Some of the monuments of the ancient world so impressed visitors from far and wide with their beauty, artistic and architectural ambition, and sheer scale that their reputation grew as must-see sights for the ancient traveller and pilgrim. Seven such monuments became the original ‘bucket list’ when ancient writers such as Herodotus, Callimachus of Cyrene, Antipater of Sidon, and Philo of Byzantium compiled shortlists of the most wonderful sights of the ancient world. The Colossus of Rhodes made it onto the established list of Seven Wonders because of its audacious size. Previously, the Greeks had applied the term ‘colossus’ to statuary of any size, but from now on, thanks to the giant figure of Helios, the term would be applied only to very large figure sculptures.

The Colossus, along with many other structures on Rhodes, was toppled by an earthquake in either 228 or 226 BCE. According to the Greek geographer and writer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – 24 CE) in his Geography, the statue snapped at the knees and then lay forlorn and untouched because the locals believed the great oracle of Delphi’s prediction that to move it would bring misfortune on the city. Pliny the Elder made the following observations on the Colossus’ awesome aspect, even when in fragments: This statue fifty-six years after it was erected, was thrown down by an earthquake; but even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior. Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of which the artist steadied it while erecting it.

Around 654 CE, according to the Byzantine historian Theophanes (c. 758 – c. 817 CE), when Rhodes was occupied by the Muslims of the Umayyad Caliphate, a Jewish merchant from the city of Edessa in upper Mesopotamia bought the bronze wreckage of the Colossus to melt down and reuse the metal, transporting it to the East using 900 camels.

NOMAD MANIA Greece – Dodecanese Islands (Rhodes, Kos, Patmos)

World Heritage Sites:

Medieval City of Rhodes

The Historic Centre (Chorá) with the Monastery of Saint-John the Theologian and the Cave of the Apocalypse on the Island of Pátmos

Tentative WHS:

Ancient Greek Theatres (16/01/2014)

Ancient Towers of the Aegean Sea (16/01/2014)

Late Medieval Bastioned Fortifications in Greece (16/01/2014)

XL:

Agathonisi

Kastelorizo (Megisti)

Islands:

KOSOS

KALYMNOS

LEROS

TILOS

ASTYPALAIA

Castles, Palaces, Forts: Astypalaia Castle

KARPATHOS

Villages and Small Towns: Olympos

Airports: Karpathos (AOK)

KOS

Airports: Kos (KGS)

Museums: Archaeological Museum

Festivals: Hippocratea Festival

PATMOS

World Heritage Sites: The Historic Centre (Chorá) with the Monastery of Saint-John the Theologian and the Cave of the Apocalypse on the Island of Pátmos

Religious Temples: Monastery of Saint John the Theologian, Patmos

RHODES

World Heritage Sites: Medieval City of Rhodes

Airports: Rhodes (RHO)

Museums: Modern Greek Art Museum

Castles, Palaces, Forts: Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes

Villages and Small Towns:

Maritsa

Rhodes town

Aquariums: Rhodes Aquarium

SYMI

Villages and Small Towns: Symi Town

I didn’t go here, but I included it for information.

THE HISTORIC CENTRE (Chorá) with the MONASTERY of SAINT-JOHN the THEOLOGIAN and the CAVE of the APOCALYPSE on the ISLAND of PATMOS

The small island of Pátmos in the Dodecanese is reputed to be where St John the Theologian wrote both his Gospel and the Apocalypse around 95AD. A monastery dedicated to the ‘beloved disciple’ was founded there in the late 10th century and it has been a place of Greek Orthodox pilgrimage and learning ever since. The fine monastic complex dominates the island. The old settlement of Chorá, associated with it, contains many religious and secular buildings.

The colonization of the Chóra of Pátmos took place gradually around the fortified monastic complex and was the centre of social life of the islanders.

The Monastery of St John the Theologian is unique in integrating a monastery within a fortified enclosure, which has evolved in response to changing political and economic circumstances for over 900 years. It has the external appearance of a polygonal castle, with towers and crenellations. It is also home to a remarkable collection of manuscripts, icons, and liturgical artwork and objects.

The earliest elements, belonging to the 11th century, are the Katholikón (main church) of the monastery, the Chapel of Panagía, and the refectory. The north and west sides of the courtyard are lined with the white walls of monastic cells and the south side is formed by the Tzafara, a two-storyed arcade of 1698 built in dressed stone, whilst the outer narthex of the Katholikón forms the east side.

The active monastic community of Pátmos continues to practice old traditions and rituals such as the Byzantine ritual of Niptir, which takes place every Wednesday of the Holy Week that marks the beginning of the Passion of Christ. The Patmiada School active since 1713 is one of the most prominent Greek schools.

Cave of the Apocalypse (Spilaion Apokalypseos). Midway along the road that winds steeply up from Skála to Chorá, it is where St John dictated the Book of Revelation and his Gospel to his disciple Prochoros. This holy place attracted a number of small churches, chapels, and monastic cells, creating an interesting architectural ensemble.

The old settlement of Chóra contains many religious and secular buildings and is one of the best preserved and oldest of the Aegean Chorá. Beginning in the 13th century, the town was expanded in the 15th century for refugees from Constantinople (the Alloteina) and in the 17th century from Crete (the Kretika). Paradoxically, perhaps, Patmos thrived as a trading centre under Ottoman occupation, reflected by fine merchants’ houses of the late 16th and 17th centuries in Chorá. The town contains a number of fine small churches dating mostly from the 17th and 18th centuries with mural paintings, icons, and other church furnishings.

Patmos is unique – Pátmos is the only example of a fortified Orthodox monastic complex integrating a supporting community, the Chorá, built around the hill-top fortifications. Chóra is one of the few settlements in Greece that have evolved uninterruptedly since the 12th century with religious ceremonies that date back to the early Christian times still being practised unchanged. The settlement is still inhabited.

LATE MEDIEVAL BASTIONED FORTIFICATIONS IN GREECE

| SITE | REGION | REGIONAL UNIT | COORDINATES |

| Corfu | Ionian islands | Corfu | 19.928385 E, 39.624538 N |

| Zakynthos | Ionian islands | Zakynthos | 20.891944 E, 37.789444 N |

| Koroni | Peloponnese | Messinia | 21.961826 E, 36.794382 N |

| Methoni | Peloponnese | Messinia | 21.700 E, 36.8150 N |

| Bourtzi- Palamidi- Akronafplia | Peloponnese | Argolis | 22.790586 E, 37.569689 N 22.804472 E, 37.561486 N 22.795028 E, 37.563869 N |

| Heraklion | Crete | Heraklion | 25.136743 E, 35.344548 N |

| Chania | Crete | Chania | 24.013659 E, 35.518245 N |

| Rhodes | South Aegean | Rhodes | 28.2270 E, 36.4450 N |

| Mytilini | North Aegean | Lesbos | 26.561829 E, 39.110116 N |

With the appearance and establishment, in the 15th century, of the use of gunpowder, a new, powerful and destructive means of warfare, city fortification practices changed. Since medieval fortifications were unable to withstand the constantly increasing artillery power, additional defensive structures began to be added to existing fortresses. This change was completed in the 16th century, establishing the “bastion system” or “fronte bastionato”, based on the principle of “flanking fire”. In the 17th century, the need to confront even greater artillery firepower led to the construction of a multitude of smaller fortifications outside the main moat, whose aim was to keep the enemy as far away as possible from the main fortifications.

These fortifications are mostly found in areas that passed into Latin hands, such as the Peloponnese, the coasts of Western Greece, the Ionian Islands, Crete and the Dodecanese. Most were built on the site of older, ancient and/or Byzantine fortifications, but their main phase was constructed during the various phases of Latin domination.

These are particularly well-preserved retaining their integrity and original layout intact to the present day as that they were built by the leading engineers of the time They are strategically positioned on the hubs of the trade routes between West and East and also North and South, and therefore played an important part as trading stations in the East Mediterranean basin.

1. Methoni Fortress

This is a typical citadel built on an exceptional natural harbour in medieval times a stop on the pilgrimage route to the Holy Land and a port for cargo ships voyaging from the West to the East. Together with Koroni, the ports are known as the “two eyes” of the Serenissima.

The city reached the peak of its prosperity in the two centuries after 1204, when it became a Venetian colony and international trading station. That was when the fortress assumed its present form with two fortified enclosures, the south one protecting the city and the north one covering the side facing the interior. The fortress came under Ottoman dominion from 1500 to the early 19th century, with a brief interlude of Venetian rule (1685-1715). In 1828, when Ibrahim Pasha surrendered Methoni to the French expeditionary corps, the inhabitants moved to the present-day town outside the walls.

The fortress covers an area of approximately 9.3 hectares. The walls are defended by a wide dry moat and reinforced with towers at intervals. Two bastions rise below the main gate with its elaborately decorated posts. The fortress has another six gates which open onto the ground floors of towers and are protected by portcullis and machicolations. Bourtzi, an octagonal tower on the sea, forms part of the Methoni seaward defences, serving various functions through the ages.

Within the walls are preserved various buildings such as the church of the Transfiguration of the Saviour (1685-1715), a square building with a pyramidal roof that served as a powder-magazine (1500-1686), two Ottoman baths and the ruins of the episcopal cathedral of the city, which was dedicated to St John the Divine and turned into a mosque after 1500.

2. Koroni Fortress

The fortress of Koroni, together with neighbouring Methoni, was one of the most important harbours of La Serenissima. The fortress, covering an area of approximately 4 hectares, was built in Byzantine times on the site of ancient Asine. In 1205 it was conquered by the Franks, before passing into the hands of the Venetians (1206-1500 & 1685-1715) and the Ottomans (1500-1685 & 1715-1821) due to its strategic location. For a brief period it was taken by the Genoese (1532-1534), while in 1770 it was held by the Russian Orlov brothers. In 1825 it was conquered by Ibrahim Pasha and in 1828 it was surrendered to the French expeditionary corps, before being ceded to Nikitaras, first garrison commander of liberated Koroni.

The two centuries of the First Venetian period (13th-15th c.) were the peak of Koroni’s power, and most of the fortifications date from that time. There are two fortified enclosures, one on the west, landward side and a larger one on the east. The enclosures are separated by a wall with rectangular towers, which is probably the only remnant of the Byzantine fortifications. This layout of the fortress was preserved unaltered throughout its long history. Today the west enclosure is occupied by the Monastery of John the Baptist (founded in 1920). The east side of the fortress was reinforced during the First Ottoman period (1500-1685) with a dry moat and two round bastions, of which the north bastion, now ruined, was used as a powder magazine and blown up by the Germans in 1941.

Within the fortress there stands today the church of St Charalambos, which was built in the late 17th c. as a Catholic church, was turned into a mosque (1715-1821), and later became an Orthodox church. The ruins of a three-aisled 8th- or 9th-century basilica, dedicated to St Sophia in early modern times, are also visible. It is worth noting that there are still people living within the walls of Koroni, as well as in the traditional village outside them.

3. Akronafplia – Bourtzi – Palamidi (Fortresses of Nafplio). Akronafplia

Akronafplia fortress formed the walled burg of Nafplio from antiquity to the end of the 15th century, when the Venetians built the lower town of Nafplio. During the Frankish period it was divided by a wall into two parts, the fortress of the Franks and the fortress of the Greeks, while in the First Venetian period another fortress, the “Castello di Toro”, was built at the east end of Akronafplia.

Bourtzi is a seaside fortress built by the Venetians circa 1470, on a rocky islet in the mouth of Nafplio harbour, which it was designed to protect. In the centre rises a tall tower with three floors, with two smaller vaulted structures below it which served as canon batteries (gun emplacements), one facing the sea and the other the land. Thick chains were stretched out from the two sides of the fortress across the harbour, which is why it was known as “Porto Catena”.

Palamidi. The fortress of Palamidi was built by the Venetians and is a true achievement, as regards both the time taken to construct it (1711-1714) and its fortifications. It consists of eight bastions, one of which was left unfinished and was completed by the Ottomans, while the last was wholly constructed by them. The bastions were independent, with their own storerooms and water cisterns, and were connected by a wall.

4. Corfu

The Old Town of Corfu, strategically located at the entrance to the Adriatic Sea, has been inscribed on the List of World Heritage Properties since 2007. It is one of the most important fortified towns in the Mediterranean. Its fortifications, technical works on a huge scale, are among the most perfect examples of Venetian fortification architecture. The present form of this impressive complex is mainly the result of the work of Venetian engineers (1386-1797), with modifications and additions dating from the period of the British Protectorate (1814-1864).

The basic core of the fortifications (Old Fortress-New Fortress-Perimeter Wall-Peripheral Forts) is preserved in good condition today. The oldest part of the fortifications is the Old Fortress, which has been through all the phases of the defensive art since Byzantine times. In its final form, it was linked to Michele Sanmicheli, who applied the “bastion system” to the west side of the walls, where the monumental gate of the Fortress stands.

The massive project of walling the town, completed in the late 16th century, included the construction of the New Fortress and the line of defence that isolated the town from the countryside and the sea. The fortifications of the New Fortress, which had two gates, one to the harbour and one to the town, were laid out on two levels. The first, lower level consists of a pentagonal bastion which protected the harbour. The Castello della Campana controls the ascent to the second level, where rise the twin bastions of the “Epta Anemoi”(Seven Winds) and one more known as Skarponas. The defences of the town were reinforced by the fortification of the three hills to the west in the first half of the 18th century and the fortification of the Vido islet by the Imperial French (1807-1814).

5. Zakynthos

The Venetian fortress at the top of the naturally fortified hill that rises over Zakynthos harbour is built on what was, according to travellers’ accounts, the site of the ancient acropolis of the island, although no traces of its fortifications remain. There is no evidence of the medieval fort that stood on the same site, except for the Byzantine church of the Saviour, part of which survives inside the Venetian fortress, and which is known to have been used as the Latin cathedral. The walls and fortifications preserved today were built in 1646-47 under the direction of Venetian engineers.

Zakynthos Fortress is a typical example of fortification architecture of the period. The enceinte is trapezoidal in shape, with an inner passageway for the movement of soldiers along the weaker east side, where most of the bastions are. The British contributed significantly to the conservation of the walls and the public buildings of the fortress, when they installed their garrison there in 1812. The fortress was abandoned by its inhabitants for good following the Union of the Ionian Islands with Greece in 1864. Excavations have brought to light archaeological material from prehistoric times to the Post-Byzantine period, demonstrating that the fortress is the longest-surviving settlement on Zakynthos. Inside the fortress there are also two Venetian powder magazines and the ruins of churches dating to the Venetian period, as well as the remains of the British government building and barracks.

6. Heraklion

Following its occupation of Crete in 1211, Venice originally preserved the existing Byzantine fortifications of the city. With the change in siege technique, it was decided to reinforce the fortifications and construct a new, extended fortified enceinte. The new Venetian walls of Heraklion (known as Candia to the Venetians) are among the greatest Venetian fortifications in the Mediterranean. They are built according to the principles of the bastion system. Their construction began in 1462, with constant modifications, supplements and additions up to the end of the Venetian period (1669). The basic design was drawn up by Michele Sanmicheli and rendered definitive by Giulio Savorgnan.

The fortified enceinte, with a perimeter of approximately seven kilometres, is triangular in shape, with the base of the triangle on the seafront, and the apex (the Martinengo Bastion) pointing inland. It consists of seven heart-shaped bastions (Sabbionara, Vitturi, Jesus, Martinengo, Bethlehem, Pantocrator and San Andrea) which defended the intervening straight sections of the fortifications, the curtain walls. For better supervision of the surrounding area, raised cavaliers shaped like truncated cones were constructed on the bastions (Martinengo, San Andrea, Vitturi, Zane). The walls were surrounded by a deep dry moat, while the system was completed by the earthen counterscarps and the outwork of San Demetrio. The main gates (St George or Lazaretto, Jesus, Pantocrator) leading out of the city into the surrounding countryside were set, for reasons of defence, in the sides of the bastions. Other, smaller military gates led up sloping galleries to the low squares of the bastions.

Set into the walls all around the perimeter of the fortifications are relief plaques bearing the winged lion of St Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of Venice, and the coats of arms of Venetian noblemen and officials.

The defences of the coastal front were further reinforced by the sea fortress (known as the “Rocca a Mare”, “Castello a Mare” or “Castello” during the Venetian period and as the “Su Kulesi” or “Koules” during the Ottoman period) at the harbour entrance, and the fortress of Paleokastro on the north coast of Heraklion Bay, both also constructed according to the “bastion system”.

7. Chania

The design of the Venetian fortifications of Chania was entrusted to the Veronese Michele Sanmicheli. The work on Chania began in 1538 and continued up to the Ottoman conquest of the city, in 1645.

The form of the fortifications followed the basic principles of the bastion system, the natural terrain and the boundaries of the city outside the walls, which would have to be protected. The fortifications also included the harbour and a round tower from the original harbour fortifications built by the Genoese in the early 13th c. The walls formed a rectangle, parallel to the seafront, reinforced by four heart-shaped bastions and an equal number of cavaliers. These are the bastions of: a) Salvatore or Gritti, b) San Andrea, c) Piattaforma and d) Santa Lucia, and the cavaliers of Priuli, Lando or Schiavo or San Demetrio, San Giovanni and Santa Maria. Access to the city was via three gates, the Porta Retimiotta, the Sabbionara and the San Salvatore Gate. Further north, facing the sea, were the Sabbionara and Mocenigo bastions, and the harbour breakwater, with the bastion of San Nicolò del Molo. The breakwater ended in the small tower of the Pharos (Lighthouse), which was lower than the present-day structure, built after 1830. On the opposite side, the Rivellino del Porto, with the Firkas Fortress, protected the harbour mouth. Inside, the fortress was laid out with barracks buildings and military stores, while it was also the seat of the military governor of the city.

During the Ottoman period, some parts of the Venetian fortifications were restructured and added to.

8. Rhodes

The medieval city of Rhodes, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1988, is an outstanding example of an architectural ensemble illustrating the major period of history in which a military hospital order, founded during the Crusades, survived in the eastern Mediterranean area, in a context characterized by an obsessive fear of siege. Rhodes, from 1309 to 1523, was occupied by the Knightly Order of St John of Jerusalem, who transformed the island capital into a fortified city able to withstand sieges as terrible as those led by the Sultan of Egypt in 1444 and Mehmet II in 1480. It was later that the island came under Turkish and Italian rule.

The ramparts of the medieval city, partially erected on the foundations of the Byzantine enclosure, were constantly maintained and remodeled between the 14th and 16th centuries under the Grand Masters Giovanni Battista degli Orsini (1467-76), Pierre d’Aubusson (1476-1505), Aiméry d’Amboise (1505-12), and Fabrizio del Carretto (1513-21).

With the Palace of the Grand Masters, the Great Hospital and the Street of the Knights, the Upper Town is one of the most beautiful urban ensembles of the Gothic period. In the Lower Town, Gothic architecture coexists with mosques, public baths and other buildings dating from the Ottoman period.

9. Mytilini

The fortress is set on a peninsula, between the two harbours of the city: the ancient (north) and the modern (south) harbour. The fortress, which covers an area of 9.1 hectares, stands on the site of the ancient acropolis of Mytilini and was one of the strongest fortresses in the Mediterranean. It was originally built in the 6th c. during the reign of the Emperor Justinian, although only three features of the Byzantine phase survive: a small Byzantine gate on the north side of the walls, the east wall of the keep and the water cistern in the Middle Fortress.

In 1355 Lesbos passed into the hands of the Gattelusi family, who completely repaired the fortress in 1373, along the general lines of the existing Byzantine fortifications. The area is divided into two parts, now known as the Upper and Middle Fortress, where the lords lived and where most of the religious and administrative buildings stood, while the local population lived in the fortified suburb of Melanoudi. All that survives of this phase today is the central fortified keep (the donjon) and the ruins of the church of St John.

The major earthquake of 1384 devastated both city and fortress. The two last Gattelusi, Domenico (1445-1458) and his brother Niccolò (1458-1462), carried out reinforcement works to the fortress, placing the first cannon there and constructing bastions and revetments, embrasures, dry moats and watchtowers.

In September 1462 the Ottomans took the city of Mytilini, after a brief but violent siege. In 1501, in the reign of Sultan Bayezid, and again in 1643/44, under Sultan Ibrahim Khan, the ruined fortifications of the north harbour were repaired, two new large, round fortification towers with gun ports were built, new walls were constructed and a dry moat was dug. The most important of the Ottoman buildings inside the fortress are the Medrese (Ottoman religious school) which included a public soup kitchen and hospice (Imaret), and the Teke (Ottoman monastery), all dated to the first half of the 16th century.

New, extensive repair works were carried out after an earthquake in 1765/66. During the course of the 19th century, the barracks next to the Medrese were constructed, together with the neighbouring powder magazine.

A particularly extensive network of medieval bastioned fortifications survives in Greece. The suggested fortifications are representative examples of the “bastion system”, characterized by the particular architectural features of the new system of defence invented to meet the constant developments of the art of war, with the widespread use of artillery. They also made masterful use of the geomorphological peculiarities of each area, exploiting their strategic location to a significant degree. Some of these fortifications are among the best-preserved fortification works in the Mediterranean area and were designed in the context of a wider defensive programme by great contemporary engineers, such as the Veronese Michele Sanmicheli.

The construction of bastioned fortifications was originally developed by Venice in the context of the realisation of a wider defensive programme for the Mediterranean area. It therefore reflects the influence of Western ideas in the field of fortification architecture during the Late Renaissance/Mannerist period in the East Mediterranean, where Byzantine fortifications were still in use. The most interesting element is the appearance of a new system of fortification, the “bastion front” or “fronte bastionato”, a landmark in the evolution of fortification technology and architecture.

The proposed fortifications are prime examples of the “bastion system” and defensive/fortification works in the East Mediterranean generally. They still preserve today, in good condition, basic features of fortification architecture, and illustrate important phases in the history of fortification architecture and, in some cases, of the towns and cities that lay within their walls, from the time they were first constructed to the later interventions they sustained, the latter being directly linked to the requirements, practices, choices and convictions of each period.

Apart from their importance to fortification architecture, the proposed fortifications are also trading stations which played a major role in the history of the East Mediterranean, and reflect the osmosis of ideas between East and West.

The “bastion system” applied to the fortification works of the Mediterranean, and particularly their design by famous contemporary architects, is also shared by the fortifications of other cities, such as Verona and Lucca in Italy, Dubrovnik in Croatia, Valetta in Malta, and Vauban in France, all monuments already inscribed on the World Heritage List.

Soldiers and politicians, travellers and merchants, immigrants and ambassadors passed through the fortresses, leaving behind testimonies both material and immaterial, whose transmission and transformation were facilitated by the maritime routes.