Dominican Republic – East, South (Santo Domingo, La Romana, Barahona) March 22-25, 2022.

Capital. Santo Domingo

Languages. Spanish

Ethnic groups. 70.4% Mixed 58.0%, Mestizo/indio, 12.4% Mulatto, 15.8% Black, 13.5% White, 0.3% Other

Religion. 66.7% Christianity: 44.3% Roman Catholic 21.3% Protestant, 1.1% Other Christian, 29.6% No religion, 0.7% Other, 2.0% Unspecified

Population. 10,878,246 (86th)

Area. 48,671 km2 (18,792 sq mi) (128th)

GDP (PPP). $20,625

GDP (nominal) $9,195

Gini. ![]() 43.7 medium

43.7 medium

Calling code. +1-809, +1-829, +1-849

Currency. Dominican Peso (DOP): March, 2022 – 1US$=54.86; 1€=60.42; 1 CAD=43.53

I spent 2 1/2 days in Santo Domingo and then rented a car to see the rest of the island over three days. I drove 1,500 km to see most of the country except the far SW and Punta Cana.

SANTO DOMINGO/BAJOS de HAINA/SAN CRISTOBAL

Day 1

I arrived from Guadeloupe to Santo Domingo in the late morning (Santo Domingo – Las Americas Airport (SDQ). There is no organized public transport from the airport. Apparently, collectivos are on the road outside the airport but don’t enter. I hailed an Uber but he refused the price listed ($15) and wanted $25 (normal taxis $35) and didn’t appear, so I shared an Uber with an American couple ($10 of a $30 fare). They were going to a resort west of SD and I got off on the “freeway” north of my hostel (La Chosa) in Colonia and walked down passing the National Palace and Mercado Modelo.

Puente Juan Bosch. A road bridge crossing the river on the way to Colonia from the airport. One half is an old steel girder and the other half a new cable suspension bridge.

National Palace. Home to the president, it can’t be entered, but 3 sides can be walked around. The large 2-story yellow stone palace has a great central dome and is surrounded by large lawns and some decorative plantings in front.

Mercado Modelo. One part has produce and the other large part knick-knacks and jewelry. The business was very slow.

Colonial City of Santo Domingo WHS. After Christopher Columbus’s arrival on the island in 1492, Santo Domingo became the site of the first cathedral, hospital, customs house, and university in the Americas. This colonial town, founded in 1498, was laid out on a grid pattern that became the model for almost all town planners in the New World.

The first permanent establishment of the « New World » and capital of the West Indies, the Colonial City of Santo Domingo – the only one of the 15th century in the Americas – was the place of departure for the spread of European culture and the conquest of the continent. From its port conquerors such as Ponce de Leon, Juan de Esquivel, Herman Cortes, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Alonso de Ojeda and many others departed in search of new lands.

Located at the mouth of the Ozama, it is the core from which Santo Domingo de Guzman, the capital of the Dominican Republic, was founded. Originally established on the east side of the Ozama in 1496, it was founded by Bartholomew Columbus in 1498. In 1502, the city was transferred to the west bank and planned with a grid pattern from the Grand Place (Plaza Mayor). This checkerboard layout later became a reference for almost all the town planners of the New World.

City of « firsts »,Santo Domingo was the headquarters for the first institutions in the Americas: Saint Mary of the Incarnation Cathedral, Saint Francois Monastery, Saint Thomas Aquinas University, Nicholas de Bari Hospital, and the Casa de Contratación. It is also the first fortified city and the first headquarters of Spanish power in the New World.

Over an area of 106 ha, bordered by walls, bastions, and forts, the city has 32 streets that criss-cross the 116 blocks, constructions of one or two levels with stone, brick, or earthen walls. Its original plan, the scale of its streets, and its buildings are almost totally intact including Gothic buildings unique in this region.and the appearance of the first indications of the Renaissance, as is eloquently illustrated in its cathedral.

City of encounters, the Dominican monk, Brother Antonio Montesino launched his appeal for the natural right of the natives, marking the beginning of the combat for the fundamental rights of mankind.

Its institutional buildings date from the 16th century – Palace of the Viceroy, Cabildo (Town Hall), Real Audiencia (Royal Court of Justice) Chancery and Cathedral.

Hostel La Chosa. Owned by an Australian, this turned out to be a good value with no AC but good fans, a nice kitchen (lots of free coffee made in bilettis), a small pool and a nice sitting area. There were a lot of small black flies at dusk and dawn. In Colonia, it is very close to Calle El Conde, a popular pedestrianized street with many restaurants, art, stores, cigar stores, and a good supermarket. Cold Play had a concert the night I arrived but tickets started at over $200 for standing room.

Day 2

Memorial Museum of Dominican Resistance. There is a lot of writing only in Spanish with many biographies. This shows the history of PR since 1916. I got little from it. 50 DP reduced

Museo de la Porcelana. Except for all the cats, this is the porcelain collection of one woman – Violeta Martinez. It is organized by country with most from France, Germany, the US, and China. 100 DP

Larimar Museum. Larimar is natural volcanic stone found only in the DR. When cut, polished and made into jewelry, it is lovely light blue color. Free

Catedral Primada de América. Dating from 1523, it is the oldest church in the Americas. It is yellow stone, looks very old and has 12 chapels (some with domes, ribbed vaults and painted ceilings, three naves, 12 columns and a lovely ribbed vaulted ceiling. 100 DP with audiocassette.

Christopher Columbus statue. In Columbus Square next to the cathedral, this bronze of Columbus is pointing with his left arm. It stands on a nice stone plinth with metal ships projecting out.

Museo Casa Duarte. The story of the first president of the DR, most of his life is demonstrated in dioramas of wax figures (not that well done). There are also old guns, and other weapons.

Museum of Rum. Show the making of rum (from black strap molasses. Has a lovely bar and the opportunity to buy rum in the gift shop. Free.

Amber World Museum. This private museum is very good with a lot of amber with insects and plants with a great explanation of the formation of amber – millions of years old, fossilized resin from pine trees and here in SD from cacao trees, mined in dirt. 200 DP

Museo Naval de las Atarazanas. Shows the treasure from shipwrecks around SD – a lot of silver. 400 DP

Alcázar de Colón. A fort on the river with a few walls and a museum in a building founded by Columbus’ son – Palacio Verrainal de Diego Colon – with mediocre info. 50 DP

Museum of the Royal Houses. A large museum with an incredible carved elephant horn and models of Columbus’ ships. 100 DP

Pantheon. In a lovely old Jesuit church, this has graves of important Dominicans.

Fortaleza Ozama. A large fort with intact walls, a large grassed parade ground, a tower and a small museum. 100 DP

Day 3

I walked along the Malecon (George Washington Ave) to see if I could rent a car. The avenue is lovely right on the water with rows of palm trees on both sides. It is lined with hotels, many with casinos.

Obelisco Hembra. On a r9und about on the Malecon, this impressive obelisk is complete painted. Very attractive.

The next three museums are in a “Cultural park”.

National Museum of Natural History. On three floors there are several “ok” dioramas with painted backgrounds, many stuffed birds and some great whale skeletons. Free reduced

Modern Art Museum. Two floors of the bad art of one man (Jose Cestico) and an upper floor with sculptures by Amaya Salazar and paintings by Dustin Munoz (some very good). 100 DP

Museum of Dominican Man. History of SD 1844 to the present. It has been closed for some time but I was shown around by a nice young guy to see the few exhibits set up: piano that first played the national anthem, Trujillos car (full of bullets as he was assassinated in 1954), and a Cuban boat.

I took the metro (~40 cents) and a collectivo (~70 cents) to get to the zoo.

Parque Zoologico Nacional. This zoo is huge with no signs that tell where things are. Take the toy train (which leaves from the entrance plaza every 15-20 minutes). This has wonderful spaces with few fences (only monkeys and apes) and animals separated by a ditch. Emu, cassowary, ostrich, white rhino, camels, bison, iguanas, peccaries, chimpanzee, lions, tigers, lemurs, monkeys, hippo, jaguar, water buffalo, cattle, red deer, ponies (playground, food, and picnic area), zebra and return to start. 150 DP

National Botanical Garden. This huge garden is entered on the west side near the southwest corner. There are lovely palm trees and many flower beds and flowering trees. Some remain in a natural state. 270 DP

I walked about a km and then took the metro to the museum.

Museo Bellapart. This museum is very difficult to find. It is on the top floor of the Honda dealership. It houses a collection of one man, Juan Bellapart who also owns the Honda dealership. Most of the paintings and sculptures are from the DR but some are also form Spain. I did not appreciate his taste in art, but it is housed in a wonderful space. Free

I took the metro and then walked about 2.5 km back to my hostel for a relatively long day.

I tried to rent a car online but found it impossible. I marked several car agencies along Geo Washington Ave and the main street above it, but all were booked out. I eventually found one at Ozari ($86/day including insurance, easily the cheapest rental agency in SD). I then drove around DR for over three days.

Day 4

Punta Cana. A road in East Santo Domingo.

National Aquarium. This is very large with many tanks (and often cloudy water). I saw few interesting fish and only a few turtles in an outside pool. 125DP.

Boca Chica. A popular white sand beach (palm trees, hotels, restaurants) protected by a small marina, mangroves and well offshore, a reef. Many old obese people.

SAN PEDRO DE MARCORIS. A particularly unattractive city.

Mauricio Báez Bridge. A lovely modern cable-stayed bridge with two large concrete towers and 4 lanes. On the highway to Punta Cana.

ROMANA

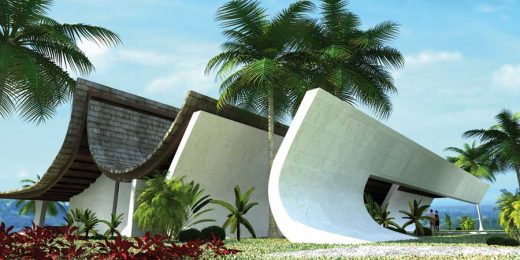

Cumayasa Building. In the NM Architectural Delights series, this is a hotel and luxury residential complex covering 1,400 hectares

It has 3,000 luxury villas, 3 hotels, 4 golf courses, a marina, tennis and ecotourism.

Altos de Chavón. In the NM Bizzarium series, it is a tourist attraction, a re-creation of a 16th century Mediterranean–style village, located atop the Chavón River. It is the most popular attraction in the city. Altos de Chavón overlooks Rio Chavón and the Dye Fore golf course of Casa de Campo; both built by former Gulf+Western chairman Charles Bluhdorn.

The project was conceived by the Italian architect Roberto Copa, and the industrialist Charles Bluhdorn. The project began in 1976 when the construction of a nearby road and bridge crossing the Chavón River had to be blasted through a mountain of stone. Charles Bludhorn, chairman of Paramount then parent Gulf+Western, had the idea of using the stones to re-create a sixteenth-century style Mediterranean village, similar to some of the architecture found in the historic center of Santo Domingo. Construction was completed in the early 1980s. Charles Bluhdorn’s daughter, Dominique Bluhdorn, is the current president of the Altos de Chavón Cultural Center Foundation.

Narrow, cobble-covered alleyways lined with lanterns and shuttered limestone walls yield several good Mediterranean-style restaurants, a number of quaint shops featuring the diverse craftwork of local artisans, and three galleries exhibiting the talents of local students.

Altos de Chavón School of Design. The on-site design school, it is an affiliate school of Parsons School of Design in New York City.

St. Stanislaus Church. With its plaza and sparkling fountain, it is a popular wedding venue. The St. Stanislaus Church was named after the patron saint of Poland, Stanislaus of Szczepanów in tribute to Pope John Paul II who visited Santo Domingo in 1979 and left some of the saint’s ashes behind.

Amphitheater. A Roman-styled 5,000-seat amphitheater hosts 20th century musical acts—The Pet Shop Boys, Frank Sinatra, and Julio Iglesias to name a few—while Génesis nightclub provides a popular dance venue for guests from the Casa de Campo resort nearby.

The Regional Museum of Archaeology contains a collection of pre-Columbian Indian artifacts unearthed in the surrounding area.

I didn’t go to East NP or Punta Cana because of time and lack of anything good to see. East NP (Cotubanamá)

Punta Cana*

Aromas Museum permanently closed

ChocoMuseo

Punta Cana beaches

The drive here was through very flat, dry country with sugar cane fields as far as one could see.

HIGUEY

Basílica Catedral Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia. Wow don’t miss this architecturally unique church. Constructed of reinforced concrete, the outside has a very narrow and tall arch. Inside it is shaped like a very tall arch. There is lovely orange geometric stained glass covering both ends and the sides of the cross, which also has frescoes. Behind the altar is a wood “scaffold” covered with large wood “leaves”. The bronze front doors have large bas relief panels dated from 1492 to 1989.

The church is surrounded by thousands of palm trees and a large field of grass.

Inaugurated in 1971, its 69-meter or 225 feet high arch, with a bronze and gold entrance is the exterior highlight. The altar holds a framed painting of the Virgin Mary dating back to the 16th century, the centerpiece of devotion. Every January 21, pilgrims from around the country flock here to pay their respects.

==============================================================

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC – NORTH (Santiago, Puerto Plata, Samaná, La Vega) Mar 25-28, 2022

Santa Cruz del Seibo. A lovely city passed through on the way to Samana.

SAMANA

This big peninsula is on the east coast of DR. The beginning is flat and the rest quite hilly.

Whale Museum. This small private museum is not very interesting. 100 DR

Puente De Cayo Samana. This must be the longest pedestrian bridge in the world. It has 3 spans, the first a short span to a headland and above a public beach, the second short to an island, and the third about 700 yards long with 15 piers to a large island with several small plazas, beaches, and an awful toilet.

Iguanario Los Tocones. This is 28 km from Samana town at the end of the peninsula. I didn’t go.

Day 5

It was 213 km to Puerto Plata. Google Maps said it would take 4+ hours and it took me 3 ¾ and I could not have driven more aggressively. Some bits were along gorgeous coast with palms and surf. But many towns were traversed causing delays – traffic, speed bumps, and slow traffic.

Playa Grand. Large beach with many resorts. This whole area is heavily touristed with many westerners.

PUERTO PLATA

(San Felipe de Puerto Plata), is the third-largest city in the Dominican Republic. Puerto Plata has resorts such as Playa Dorada and Costa Dorada, which are located east of the city proper. There are 100,000 hotel beds in the city.

The fortification Fortaleza San Felipe, which was built in the 16th century and served as a prison under Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorship, lies close to the port of Puerta Plata. The amber museum, is also a well-known attraction in this city. La Isabela, a settlement built by Christopher Columbus, is located near Puerto Plata. In April 1563, the Spanish settlement became notorious when the English slave trader Sir John Hawkins brought 400 people he had abducted from Sierra Leone. Hawkins traded his victims with the Spanish for pearls, hides, sugar, and some gold. This was the start of British involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The city sits on land that rises abruptly from the sea making it almost completely visible from the port. It is bordered on the north by the Atlantic Ocean and to the south and southwest by the hill Isabel de Torres.

The small bay around which the city was built provides a natural harbor. Puerto Plata is the largest city on the northern seaboard. The mountain Isabel de Torres is situated some 5 km to the southwest of the city of San Felipe. It is possible to drive to the top of the mountain by following the highway Don José Ginebra. At the summit, there is a tropical botanical garden covering about 7 acres (28,000 m2), featuring 600 varieties of tropical plants.

Climate. Puerto Plata has a tropical monsoon climate, with hot, somewhat wet summers and warm, very wet winters

History. Since the founding of La Isabela, the first village in the New World, on January 2, 1494, Puerto Plata has been a town of firsts in the Americas.

Historians are not clear on the exact year of Puerto Plata’s founding but was between 1503-06.

Christopher Columbus, on his first trip, called the mountain Monte de Plata, observing that since the top is frequently foggy it had a silver-like appearance, hence the name of the port. Around 1555, Puerto Plata’s importance as a port town was lost and it became one of the places of the Antilles frequented by pirates.

In 1605 it was depopulated and destroyed by order of Felipe III, to hinder the advance of English piracy. A hundred years later the town was repopulated with farmers originating from the Canary Islands.

From 1822 to 1844 the city was under Haitian control. From 1844 on began the period of the republic, in which the city began to recover its maritime and commercial boom. The city grew under the influence of European immigrants, who left a cultural and social footprint that remains unique among other cities on the island.

In 1863, during the Dominican Restoration War, the city was razed completely. Beginning in 1865, the current Puerto Plata began to be built. This explains the Victorian style of much of its current architecture. By the end of the 19th century, Puerto Plata had become important for its cultural, social, maritime, and economic development.

In 1996, Birgenair Flight 301 crashed near Puerto Plata, killing all 189 people on board.

Brugal Rum Distillery. The largest producer of traditionally made rum in the DR since 1888, Brugal is aged in around 200,000 American white oak barrels on-site at the distillery in Puerto Plata city. Tours of the distillery are available to learn about the making of this popular brand, and end with rum tasting, as well as the chance of purchasing well-priced premium rums on-site. A large distillery but with no tours.

Historical Centre of Puerto Plata Tentative WHS: (21/11/2001). Centered around the central square and extending down to the water, the buildings are lovely pastel 2-story with balconies.

Casa Museo General Gregorio Luperon. This is the home of Luperon, a lovely small 2-story blue house with white balconies on a residential street. It showcases his life through various exhibits. Gregorio Luperón was born 1839 in Puerto Plata. $5.

Luperon (1839 –1897) was a Dominican president, military general, businessman, liberal politician, freemason, and Statesman who was one of the leaders in the Restoration of the Dominican Republic after the Spanish annexation in 1863.

Luperón was an active member of the Triunvirato of 1866, becoming the President of the Provincial Government in San Felipe de Puerto Plata, and after the successful coup against Cesareo Guillermo, he became the 28th President of the Dominican Republic. During his government in 1879, he incentivized secularism in the Dominican Republic

Catedral San Felipe. This lovely church is 3-nave with large arches giving it light airy feeling. It has wonderful stained glass. It sits on the south of the square.

Puerto Plata Lighthouse. Sitting on the hill next to the fort, this unusual LH is supported on 8 round steel girders with a central stairway.

Fortaleza San Felipe. This small fort sits on the point of land with great views of the ocean and port. The fort is surrounded by manicured lawns and hedges. It has low stone walls and two low round corner towers. Inside a shallow moat separates the round central “keep”. The museum is not so interesting. 100 DP

Puerto Plata Cable Car. The first aerial tramway of the Caribbean it goes up to the Pico Isabel de Torres, a 793-meter (2600-foot) high mountain within the city. $10 or 580 DP

Christ the Redeemer (Cristo Redentor). On the top of Isabel de Torres, this is a 16m tall tall bronze on top of a half dome. It is an exact copy of Rio’s Christ the Redeemer which is 32m tall and made of concrete.

Playa Rincon. A nice beach at the far eastern end of the malecon.

27 Waterfalls (27 Charcos). The original and best known of the area’s falls, it is a moderately strenuous hike of around 70 minutes that leads up to the top of the falls where the real fun begins as you jump, slide and swim your way back down to base camp, Total river time approx. 2.5 hours. Jumps of up to 8m/25ft. Iguana Mama is the only tour company that goes all the way to No.27.

The name 27 “Waterfalls” is actually a mistranslation from the Spanish word “Charcos” that means pools not waterfalls, there are only in fact a total of around 12 actual waterfalls even on the full trip to number 27.

Sitio Arqueológico de la Villa La Isabela. Villa Isabela was the first European settlements in America. The first settler of the village was Christopher Columbus, who in 1494, during his second travel to America, settled there together with 1500 colonisers. But in 1500, the city was abandoned due to the violent hurricanes that destroyed it. In the 20th Century, this little village was rediscovered and now has the Archaeological Museum of La Isabela, the graveyard, and Christopher Columbus’s House.

After Trujillo mistakenly ordered the site destroyed, all the buildings were pushed into the ocean and all that remains are rocks marking the boundaries of the church, several houses and the low foundation walls of Columbus’ house. Take a guided tour with a fellow with passable English. 100 DP

Santuario de Mamíferos Marinos Bancos de La Plata y Navidad (Marine Mammals Sanctuary was created in 1986, one of the first protected areas of this nature established worldwide and the first sanctuary of marine mammals created in the Atlantic Ocean. It is made up of the Banco de la Plata, the Banco del Pañuelo and the Banco de la Navidad, part of the Samaná bay. Its main attraction is humpback whales between the months of January and April, when these marine mammals move to the area to mate and give birth. The Sanctuary is considered a critical habitat for the survival of the humpback whale. It has coral reefs, mangroves and marine grasslands. Also protected are whales, dolphins, manatees, marine turtles, pelagic fish of commercial importance and invertebrates such as lambi.

There are a large number of shipwrecks Guadalupe and Tolosa galleons, sunk by a hurricane in 1724, the Conception, sunk in 1641 in the Silver bank; the Scipion, a French ship of war sunk in 1782 and the wreck of the Golden Fleece, the boat of the pirate Bannister sunk in 1686.

The only possible trips here are in small boats from the small towns of ??? to see manatees and dolphins. They don’t go beyond the reef and you can’t see whales (tours only from Semana.

Montecristi Tentative WHS. (21/11/2001). The city of Montecristi is inserted in a natural environment, in which the highlights is the giant silhouette of the ‘El Morro” next to the islet Pablillo, they seem to be remainders of an old mountain rance, beside the beach of Bolaños. The environment of Montecristi is framed by the end of the Northern mountain range, for the hill of the Guano and the hill Isabel de Torres. The area historical bill wide streets to grid, most asphalted. The houses built in wood and roof of zinc, of a rich and beautiful Victorian style, unique in the country, they represent a time of peace and economic development of the city, in the XXIII and XIX century.

Montecristi NP. The northwest border province of Montecristi is a wild and striking landscape with rice plantations, banana fields, goats and giant cacti, salt ponds and limestone cliffs. Part desert and part Mediterranean-like scenery, thick mangrove tunnels give way to fresh lagoons, offshore cayes teem with migratory birds and white sand beaches. Founded in 1506, its t inhabitants were moved due to illegal trading and smuggling with foreign pirates.

El Morro de Montechristi. A large ridge on the ocean in the park.

House Museum Of Máximo Gómez. He was born in Bani and retired in Havana but lived in Montechristi.(1836 – 1905), was a Dominican Major General in Cuba’s Ten Years’ War (1868–1878) against Spain. He was also Cuba’s military commander in that country’s War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains and torching the Spanish loyalists’ property and sugar plantations—including many owned by Americans. He greatly increased the efficacy of the attacks by torturing and killing not only Spanish soldiers, but also Spanish sympathizers. By the time the Spanish–American War broke out in April 1898, Gómez had the Spanish forces on the ropes. He refused to join forces with the Spanish in fighting off the United States, and he retired to a villa outside of Havana after the war’s end.

Day 6

Davidoff Factory. A large very attractive cigar factory.Good tour.

Jacagua, Villa of Santiago Tentative WHS. (21/11/2001) (Los Cocos de Jacagua (officially Distrito Municipal San Francisco de Jacagua ) is a municipal district of the Santiago de los Caballeros municipality.

History. The town of Santiago was moved from the banks of the Yaque River to Los Cocos de Jacagua in 1504 for unknown reasons. The first church of “Tapia y techo de Santo Domingo” was built in this new town, of which the ruins exist within the land belonging to the Benoit family. It lasted 58 years as in 1562 a great earthquake hit the area and destroyed all the buildings, forcing its inhabitants to return to an area adjacent to the bank of the Yaque River. It is known as Old Santiago. It is centered around the remains of the old church as overgrown ruins on private property.

It was not possible to find this on Google Maps.

SANTIAGO/MOCA

It was a Sunday and difficult to navigate the city because of a bicycle race, road construction and Dominicans are very out and about on this day.

La Aurora Cigar Factory. Arrange a tour through the office. Learn how to smoke a cigar.

Monumento a los Héroes de la Restauración. A mammoth monument on a hill in a park with a large three-story base and a big column with a bronze figure with outstretched arms.

Luis Fortress. This active fort has a large clocktower, artillery/armoured vehicles and the busts of 20 heroes. Free

St. James the Apostle Cathedral. A lovely large 3-nave church with large arches and great stained glass high up. Free

Centro Leon. A large opulent modern museum with a Caribbean anthropology section and a modern art museum on the second floor was not interesting. 150 DP

LA VEGA Tentative WHS: Archaeological and Historical National Park of Pueblo Viejo, La Vega (#) (21/11/2001). I spent at least an hour trying to find this as the above name has no relation to what it is. I believe that the proper name is the Ruins of Concepcion. I drove around it but could see no trail or access. The locals were of no help.

Immaculate Conception Cathedral. This is a very odd-looking church – modern, precast concrete with odd towers, two round brick structures, and large black metal doors.

Unfortunately it was closed on a Sunday afternoon.

I didn’t see any of the following in the north.

Cities of the Americas

Sabaneta

San Francisco de Marcoris.

Villages and Small Towns: Jarabacoa

Art Museums: Sosua: Mundo King art museum

House and Biographical Museums: Tenares: Casa Museo Hermanas Mirabal

World of Nature

El Choco NP

Jose Armando Bermúdez NP

La Salcedoa Scientific Reserve

Pico Diego de Ocampo Natural Monument

Valle Nuevo NP

Botanical Gardens: Las Terrenas: Shaggy’s Paradise Botanical Garden

Waterfalls: El Limon Waterfall

Festivals: Dominican Republic Jazz Festival

Beaches

Bolaños Island beaches

Playa Dorada

Well-being: Factories: Sendero del Cacao

==============================================================

After visiting everywhere in the north of the country, I returned to the south.

Domincan Republic South

BONAO

Museo de Arte Candido Bidó. An art museum. Three large murals are on the side facing a small square and the church. It exhibits local plastic and folk arts with great masters of Dominican plastic art stand out, including Cándido Bidó, Guillo Pérez, Elsa Núñez, Alonso Cuevas.

Arte Rupestre Prehispanico en Republica Dominicana Tentative WHS

The pre-Hispanic rock art of the Dominican Republic is located in caves, shelters and open-air rocks scattered throughout the DR – on the coast, valleys and mountains. 20% of 247 described caves contain rock art – 247 are described. There are three types of rock art: paintings, petroglyphs and bas-reliefs. Petroglyphs have two groups: mural petroglyphs and geometric petroglyphs. The bas-reliefs are both mural and geometric. Such an extensive set of caves spanning 5000 years is unique showing the life and culture of the ancient inhabitants of the Caribbean.

There are three basic schools of rock art: three different schools of rock painting and two of petroglyphs.

1. Geometric (oldest school dates from the first settlers of the island who arrived 5,000 years ago, probably from Cuba, where they in turn arrived from Florida or Yucatan, with paintings and petroglyphs).

2. José María. Also old, this school includes José María Cave and Ramoncito Cave in the National Park of the East

3. Borbón (the most recent, ascribed to farming peoples of the first and second millennium after Christ). Cave No. 2 of Borbón in the Cuevas de Borbón or Pomier Anthropological Reserve

Ferrocarril cave in Los Haitises National Park

La Colmena Cave in the Jaragua National Park

The caves show technical innovations in the manufacture of pigments, their application and the use of the telluric matter of the stone support. They were used as habitation sites, centres of worship or funeral places. The art has religious, funerary or mythological themes, flora and fauna of the island, data on the Antillean pre-Hispanic calendar, images of their deities and even ideograms and hieroglyphs made by the shamans.

I went to Pomier Anthropological Reserve (Cuevas de Borbón). Near the cave, drive on a rough dirt road through a quarry. There is one cave with 4 entrances. One needs a guide as the art is not easy to find and relatively high, most 8-9 feet off the ground. He also had a good flashlight. The cave has surprisingly good construction. Walk along paths bounded by a cement retaining wall, climb up, and then back down 200 steps. The only petroglyph is a man’s face on a knob hanging down from the ceiling. There are not that many pictographs or much variety, all black charcoal mainly birds but also a man and some fish. There were many small black bats, but few speliotherms, one stalactite, one stalagmite, and a flow formation. Enter one side with a large cavern and several branching lines and exit at the other end. 500 DP cash only.

Primeros Ingenios Coloniales Azucareros de América. Tentative WHS. A tour of the oldest industry in the New World: the sugar mills. During the sixteenth century, the island of La Española was the main producer of the American sugar trade in the Caribbean and also the first colony where the agriculture of sugarcane and sugar production was introduced and disseminated to the rest of America.

Serial properties integrated by four archaeological sites, vestiges of the first colonial sugar mills in America, built by Europeans on the island of Hispaniola at the beginning of the 16th century to produce sugar and its derivatives. The complexes were located on rivers and forests for the supply of water and wood for energy; it also permitted the fluvial transport of the products from the factories to the adjacent ports. For its links with the history of slavery in the Caribbean region those mills are illustrative cases of the Slave Route’s Memory Sites.

I only went to the first mill.

Ingenio de Boca de Nigua (N18 22 21.30 E70 03 8.625): Horses moved the trapiche built in the sixteenth century and rebuilt in the eighteenth century. The mill consists in a group of buildings constructed with brick and stone masonry: a boiler house (a two-story building, the ground floor has a vaulting web ceiling and was used for the installation of ovens, while the second floor served for the installation of cauldrons or pails in a continuous arrangement); the mill (with a polygonal plan, is reinforced on each side by masonry buttresses covered with bricks, the mill´s trapiche used to squeezed the canes was installed in it center with a stone ramp facilitated the transportation of the raw materials and the finished products); the warehouses, drying rooms and warehouses were organized around a central patio.

Boca de Nigua is the site where the second-largest slave rebellion of the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo happened in 1796.

Ingenuity of Diego Caballero. (N18 21 58.85 E70 03 38.40). The old brick and stone masonry mill used water power from the Nigua River: boiler house (five furnaces and pans arranged in a continuous way); purge house (molds used to solidify the cane juices after being cooked; the mill; water supply and drainage canals built of stone, brick and rammed earth, led the water from the Nigua River); a two-story owner´s house; a chapel with a single ship, a two gable roof, an apse covered by a dome of half orange in bricks and the bell tower; and a warehouse.

Engombe sugar mill. Despite being built on a river, this mill was not hydraulic as a dam could not be made from the river because it was too high. The site name has an African origin and comes from the Bantu word “ngombé” which means “cattle” or “cow”. The set is composed for various buildings made out of stone: a polygonal mill, a boiler house, and a warehouse.

Ingenio de Palavé (N18 28 49.62 E70 02 5.10): Two-story brick masonry house built in the 17th century on a land that belonged to San José cacao farm. The façade is composed by a central portico with three arches and four columns (two exempt columns and two attached) crowned by bulrush and pinnacles. From the ground floor a stair affords independent access to the bedroom side located upstairs.

Hermitage of San Gregorio de Niguad. Has the only Virgin of La Altagracia with earrings, the product of an African transculturation as the entire city was surrounded by black settlements.

BANI

A large and very busy city between the sugar mills and Azua. I drove through it twice.

Máximo Gómez NP. A small urban park in the middle of Bani. Has trees, flowering bushes, and a bust of Maximo Gomez.

He was born in Bani and retired in Havana but lived in Montechristi.(1836 – 1905) was a Dominican Major General in Cuba’s Ten Years’ War (1868–1878) against Spain. He was also Cuba’s military commander in that country’s War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains and torching the Spanish loyalists’ property and sugar plantations—including many owned by Americans. He greatly increased the efficacy of the attacks by torturing and killing not only Spanish soldiers, but also Spanish sympathizers. By the time the Spanish–American War broke out in April 1898, Gómez had the Spanish forces on the ropes. He refused to join forces with the Spanish in fighting off the United States, and he retired to a villa outside of Havana after the war’s end.

City of Azúa de Compostela Tentative WHS (21/11/2001) (pop 23,242). (also simply Azua) is 100 kilometres west of Santo Domingo.. Founded in 1504, Azua is one of the oldest European settlements in the Americas.

Azua is known for important battles: the Battle of Azua (battle of March 19), the battle of El Número and the battle of El Memiso over the independence La Español Island. Several monuments were built to remember these significant dates. The Park of 19 de Marzo dedicated to the Battle of Azua (battle of March 19).

Other tourist attractions are the Cathedral of Azua, which has its plain colonial style and white facade. Duarte Park is the favourite place to relax for the Dominicans.

I drove back from here in the dark. There was an endless line of traffic returning to Santo Domingo on a Sunday evening. I passed hundreds of cars and earned my DR “driving badge”.

Torre Canay. A modern skyscraper in west Santo Domingo.

I returned to La Choza Hostel for the night and got up at 5 to return my rental car and get to Caribe Tours for the 6-hour bus ride to Cap Haitian in Haiti (1795 DP + US$37 border pass). I took the Metro two stops to near Caribe Tours. It was a cool, rainy day and a great day to be on a bus. We left at 08:15

I didn’t see any of these in the south.

Parque Nacional Cotubanamá (Parque Nacional del Este) is one of the most cave riddled and adventure-packed national parks in the DR—understandably one of its most visited—counting more than 500 flora species, 300 types of birds, and including long stretches of diamond white beaches on Saona and Catalina islands, along with their underwater marine life. Visitors can hike the land portion, accessible from Bayahíbe village, to explore a handful of the park’s cave and freshwater springs along marked trails of varying difficulty, or go birdwatching. On the coastline, snorkeling and diving sites are numerous along colorful coral reefs, and steep walls teeming with sea life. Onshore, the park’s sparkling beaches, particularly on Saona Island, is the most important turtle-nesting site in the Dominican Republic.

Jaragua National Park Tentative WHS (21/11/2001). Located on the southern tip of Pedernales. this is one of the Dominican Republic’s most significant natural reserves. Part of the first UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in the DR, the Jaragua National Park’s 1,295 square kilometers (500 square miles) encompass diverse ecosystems–from sea to land, lagoon to isles, Taino caves, the stunning Bahía de Las Águilas virgin coastline, and the secluded offshore isles of Beata and Alto Velo. The wildlife and fauna are a match in diversity. Fauna spotted at Jaragua National Park range from manatees, and turtles that nest on its beaches–hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, and green sea. At least 400 species of flora have been identified, including tropical forests, cacti, mangroves, and wetlands where over 130 species of birds thrive, 10 of which are endemic. You’ll see large flocks of American flamingos, white-crowned pigeons, as well as white ibis, osprey, back-crowned night herons, roseate spoonbills, and blue herons, among others. Iguanas also call the park home, from the endangered rhinoceros iguana to Ricord’s, the Hispaniolan solenodon, and the Hispaniolan hutia.

Nuestra Señora de Monte Alegre or la Duquesa Sugar Mill [Ruta de Los Ingenios] Tentative WHS (05/04/2002). La Duguesa Sugar mill was founded in 1882 by American machinist Alejandro Bass and F. Von Krosigh is located in the Distrito Nacional (National District) of the Dominican Republic. It is impossible to find this mill. A YouTube video shows it as a complete ruin.

Cities of the Americas

BARABONA

COTUI

SAN JUAN de la MANGUANA

XL

Isla Cabritos

Las Caobas Reserve Area

Southeastern capes (Cabo Falso, Cabo Beata)

Well-being: Factories: Davidoff Factory Tour

World of Nature

Jaragua NP

Loma Barbacoa Scientific Reserve

Miguel Domingo Fuerte Natural Monument

Sierra de Baoruco NP

Caves and Sinkholes

Cueva de las Maravillas

Cueva Fun Fun

Lakes

Lago de Oviedo

Lake Enriquillo

Rivers: Artibonite River marked in Haiti

Beaches

Bahía de Las Águilas

Bavaro Beach

Juanillo Beach

M@P

Isla Beata

Isla Saona

Experiences

Cocolo dance drama tradition

Quinceañera/Festa de quince/Festa de debutantes

OBSERVATIONS DR

1. People. Almost universally black, there appears to be a lot of poverty. A whole generation of young men appears to do little but ride around on their motorcycles and sit in the frequent bars that play music at deafening levels. I expected to see a lot of baseball diamonds but saw almost none. Sports don’t seem too popular.

2. Drivers. Possibly the worst drivers I have ever encountered, they range from mad racers driving at tremendous speeds to overly cautious. Most “crawl” over the many speed bumps (most very steep and very frequent in towns). On highways, they pay no attention to the fast and slow lanes, and most drive with brights on at night.

3. Motocyclists. Easily the most common way to get around in DR. It would be interesting to find the death and serious injury stats as they follow no rules – zero helmets, ignor red. lights, drive on the wrong side, often have no tail lights at night, and carry a lot of cargo. They are always in the way making passing difficult. They get very indignant it treated them like they treat others.

4. Lotteries. Easily the dominant building in the DR, there are at least 5 lotteries, each with their own kiosks, usually manned and often busy. A sign of poor countries, only poor people who can least afford it, buy these tickets.

GENERAL INFORMATION

The Dominican Republic is located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with Haiti, making Hispaniola one of only two Caribbean islands, along with Saint Martin, that is shared by two sovereign states. The Dominican Republic is the second-largest nation in the Antilles by area (after Cuba) at 48,671 square kilometers (18,792 sq mi), and third-largest by population, with approximately 10.8 million people (2020 est.), of whom approximately 3.3 million live in the metropolitan area of Santo Domingo, the capital city. The official language of the country is Spanish.

The native Taíno people had inhabited Hispaniola before the arrival of Europeans, dividing it into five chiefdoms. They had constructed an advanced farming and hunting society, and were in the process of becoming an organized civilization. The Taínos also inhabited Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the Bahamas. The Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus explored and claimed the island for Castile, landing there on his first voyage in 1492. The colony of Santo Domingo became the site of the first permanent European settlement in the Americas and the first seat of Spanish colonial rule in the New World. In 1697, Spain recognized French dominion over the western third of the island, which became the independent state of Haiti in 1804.

After more than three hundred years of Spanish rule, the Dominican people declared independence in November 1821. The leader of the independence movement, José Núñez de Cáceres, intended the Dominican nation to unite with the country of Gran Colombia, but the newly independent Dominicans were forcefully annexed by Haiti in February 1822. Independence came 22 years later in 1844, after victory in the Dominican War of Independence. Over the next 72 years, the Dominican Republic experienced mostly civil wars (financed with loans from European merchants), several failed invasions by its neighbour, Haiti, and a brief return to Spanish colonial status, before permanently ousting the Spanish during the Dominican War of Restoration of 1863–1865. During this period, two presidents were assassinated (Ulises Heureaux in 1899 and Ramón Cáceres in 1911).

The U.S. occupied the Dominican Republic (1916–1924) due to threats of defaulting on foreign debts; a subsequent calm and prosperous six-year period under Horacio Vásquez followed. From 1930 the dictatorship of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo ruled until his assassination in 1961. Juan Bosch was elected president in 1962 but was deposed in a military coup in 1963. A civil war in 1965, the country’s last, was ended by U.S. military intervention and was followed by the authoritarian rule of Joaquín Balaguer (1966–1978 and 1986–1996). Since 1978, the Dominican Republic has moved toward representative democracy, and has been led by Leonel Fernández for most of the time after 1996. Danilo Medina succeeded Fernández in 2012, winning 51% of the electoral vote over his opponent ex-president Hipólito Mejía. He was later succeeded by Luis Abinader in the 2020 presidential election.

The Dominican Republic has the largest economy (according to the U.S. State Department and the World Bank) in the Caribbean and Central American region and is the seventh-largest economy in Latin America. Over the last 25 years, the Dominican Republic has had the fastest-growing economy in the Western Hemisphere – with an average real GDP growth rate of 5.3% between 1992 and 2018. GDP growth in 2014 and 2015 reached 7.3 and 7.0%, respectively, the highest in the Western Hemisphere. In the first half of 2016, the Dominican economy grew 7.4% continuing its trend of rapid economic growth. Recent growth has been driven by construction, manufacturing, tourism, and mining. The country is the site of the third largest gold mine in the world, the Pueblo Viejo mine. Private consumption has been strong, as a result of low inflation (under 1% on average in 2015), job creation, and a high level of remittances. Illegal Haitian immigration is a big problem in the Dominican Republic, putting a strain on the Dominican economy and increasing tensions between Dominicans and Haitians. The Dominican Republic is also home to 114,050 illegal immigrants from Venezuela.

The Dominican Republic is the most visited destination in the Caribbean. The year-round golf courses are major attractions.

A geographically diverse nation, the Dominican Republic is home to both the Caribbean’s tallest mountain peak, Pico Duarte, and the Caribbean’s largest lake and lowest point, Lake Enriquillo. The island has an average temperature of 26 °C (78.8 °F) and great climatic and biological diversity. The country is also the site of the first cathedral, castle, monastery, and fortress built in the Americas, located in Santo Domingo’s Colonial Zone, a World Heritage Site. Baseball is the de facto national sport.

The name Dominican originates from Santo Domingo de Guzmán (Saint Dominic), the patron saint of astronomers, and founder of the Dominican Order.

The Dominican Order established a house of high studies on the colony of Santo Domingo that is now known as the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, the first University in the New World. They dedicated themselves to the education of the inhabitants of the island, and to the protection of the native Taíno people who were subjected to slavery.

For most of its history, up until independence, the colony was known simply as Santo Domingo – the name of its present capital and patron saint, Saint Dominic – and continued to be commonly known as such in English until the early 20th century. The residents were called “Dominicans” (Dominicanos), the adjectival form of “Domingo”, and as such, the revolutionaries named their newly independent country the “Dominican Republic” (la República Dominicana).

HISTORY

Pre-European history. The Arawakan-speaking Taíno moved into Hispaniola from the northeast region of South America, displacing earlier inhabitants, c. 650 C.E. They engaged in farming, fishing, hunting and gathering. The fierce Caribs drove the Taíno to the northeastern Caribbean, during much of the 15th century.

The Spaniards arrived in 1492. Initially, after friendly relationships, the Taínos resisted the conquest. Within a few years after 1492, the population of Taínos had declined drastically, due to smallpox, measles, and other diseases that arrived with the Europeans.

The first recorded smallpox outbreak, in the Americas, occurred on Hispaniola in 1507. The last record of pure Taínos in the country was from 1864. Still, Taíno biological heritage survived to an important extent, due to intermixing. Census records from 1514 reveal that 40% of Spanish men in Santo Domingo were married to Taíno women, and some present-day Dominicans have Taíno ancestry. Remnants of the Taíno culture include their cave paintings, such as the Pomier Caves, as well as pottery designs, which are still used in the small artisan village of Higüerito, Moca.

European colonization. Christopher Columbus arrived on the island on December 5, 1492, during the first of his four voyages to the Americas. He claimed the land for Spain and named it La Española, due to its diverse climate and terrain, which reminded him of the Spanish landscape. In 1496, Bartholomew Columbus, Christopher’s brother, built the city of Santo Domingo, Western Europe’s first permanent settlement in the “New World”. The Spaniards created a plantation economy on the island. The colony was the springboard for the further Spanish conquest of America and for decades the headquarters of Spanish power in the hemisphere.

The Taínos nearly disappeared, above all, due to European infectious diseases. Other causes were abuse, suicide, the breakup of family, starvation, the encomienda system, which resembled a feudal system in Medieval Europe, war with the Spaniards, changes in lifestyle, and mixing with other peoples. Laws passed for the native peoples’ protection (beginning with the Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513) were never truly enforced. African slaves were imported to replace the dwindling Taínos.

After its conquest of the Aztecs and Incas, Spain neglected its Caribbean holdings. Hispaniola’s sugar plantation economy quickly declined. Most Spanish colonists left for the silver-mines of Mexico and Peru, while new immigrants from Spain bypassed the island. Agriculture dwindled, new imports of slaves ceased, and white colonists, free blacks, and slaves alike lived in poverty, weakening the racial hierarchy and aiding intermixing, resulting in a population of predominantly mixed Spaniard, Taíno, and African descent. Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on contraband trade, which, along with livestock, became one of the main sources of livelihood for the island’s inhabitants.

In the mid-17th century, France sent colonists to settle the island of Tortuga and the northwestern coast of Hispaniola (which the Spaniards had abandoned by 1606) due to its strategic position in the region. In order to entice the pirates, France supplied them with women who had been taken from prisons, accused of prostitution and thieving. After decades of armed struggles with the French settlers, Spain ceded the western coast of the island to France with the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, whilst the Central Plateau remained under Spanish domain. France created a wealthy colony on the island, while the Spanish colony continued to suffer economic decline.

On April 17, 1655, English forces landed on Hispaniola, and marched 30 miles overland to Santo Domingo, the main Spanish stronghold on the island, where they laid siege to it. Spanish lancers attacked the English forces, sending them careening back toward the beach in confusion.

18th century. The House of Bourbon replaced the House of Habsburg in Spain in 1700, and introduced economic reforms that gradually began to revive trade in Santo Domingo. The crown progressively relaxed the rigid controls and restrictions on commerce between Spain and the colonies and among the colonies. The last flotas sailed in 1737; the monopoly port system was abolished shortly thereafter. By the middle of the century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and importation of slaves was renewed.

Santo Domingo’s exports soared and the island’s agricultural productivity rose, which was assisted by the involvement of Spain in the Seven Years’ War, allowing privateers operating out of Santo Domingo to once again patrol surrounding waters for enemy merchantmen. Dominican privateers in the service of the Spanish Crown had already been active in the War of Jenkins’ Ear just two decades prior, and they sharply reduced the amount of enemy trade operating in West Indian waters. The prizes they took were carried back to Santo Domingo, where their cargoes were sold to the colony’s inhabitants or to foreign merchants doing business there. The enslaved population of the colony also rose dramatically, as numerous captive Africans were taken from enemy slave ships in West Indian waters.

Between 1720 and 1774, Dominican privateers cruised the waters from Santo Domingo to the coast of Tierra Firme, taking British, French, and Dutch ships with cargoes of African slaves and other commodities. During the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), Dominican troops, shoulder to shoulder with Mexicans, Spaniards, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans fought under General Bernardo de Gálvez’ command in West Florida.

The colony of Santo Domingo saw a population increase during the 18th century, as it rose to about 91,272 in 1750. Of this number, approximately 38,272 were white landowners, 38,000 were free mixed people of color, and some 15,000 were slaves. This contrasted sharply with the population of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) – the wealthiest colony in the Caribbean and whose population of one-half a million was 90% enslaved and overall, seven times as numerous as the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo. The ‘Spanish’ settlers, whose blood by now was mixed with that of Taínos, Africans, and Canary Guanches, proclaimed: ‘It does not matter if the French are richer than us, we are still the true inheritors of this island. In our veins runs the blood of the heroic conquistadores who won this island of ours with sword and blood. As restrictions on colonial trade were relaxed, the colonial elites of Saint-Domingue offered the principal market for Santo Domingo’s exports of beef, hides, mahogany, and tobacco. With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, the rich urban families linked to the colonial bureaucracy fled the island, while most of the rural hateros (cattle ranchers) remained, even though they lost their principal market.

Inspired by disputes between whites and mulattoes in Saint-Domingue, a slave revolt broke out in the French colony. Although the population of Santo Domingo was perhaps one-fourth that of Saint-Domingue, this did not prevent the King of Spain from launching an invasion of the French side of the island in 1793, attempting to seize all, or part, of the western third of the island in an alliance of convenience with the rebellious slaves. In August 1793, a column of Dominican troops advanced into Saint-Domingue and were joined by Haitian rebels. However, these rebels soon turned against Spain and instead joined France. The Dominicans were not defeated militarily, but their advance was restrained, and when in 1795 Spain ceded Santo Domingo to France by the Treaty of Basel, Dominican attacks on Saint-Domingue ceased. After Haiti received independence in 1804, the French retained Santo Domingo until 1809, when combined Spanish and Dominican forces, aided by the British, defeated the French, leading to a recolonization by Spain.

Ephemeral independence. After a dozen years of discontent and failed independence plots by various opposing groups, Santo Domingo’s former Lieutenant-Governor (top administrator), José Núñez de Cáceres, declared the colony’s independence from the Spanish crown as Spanish Haiti, on November 30, 1821. This period is also known as the Ephemeral independence.

Unification of Hispaniola (1822–44). The newly independent republic ended two months later under the Haitian government led by Jean-Pierre Boyer.

As Toussaint Louverture had done two decades earlier, the Haitians abolished slavery. In order to raise funds for the huge indemnity of 150 million francs that Haiti agreed to pay the former French colonists, and which was subsequently lowered to 60 million francs, the Haitian government imposed heavy taxes on the Dominicans. Since Haiti was unable to adequately provision its army, the occupying forces largely survived by commandeering or confiscating food and supplies at gunpoint. Attempts to redistribute land conflicted with the system of communal land tenure (terrenos comuneros), which had arisen with the ranching economy, and some people resented being forced to grow cash crops under Boyer and Joseph Balthazar Inginac’s Code Rural. In the rural and rugged mountainous areas, the Haitian administration was usually too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation were most acutely felt, and it was there that the movement for independence originated.

The Haitians associated the Roman Catholic Church with the French slave-masters who had exploited them before independence and confiscated all church property, deported all foreign clergy, and severed the ties of the remaining clergy to the Vatican. All levels of education collapsed; the university was shut down, as it was starved both of resources and students, with young Dominican men from 16 to 25 years old being drafted into the Haitian army. Boyer’s occupation troops, who were largely Dominicans, were unpaid and had to “forage and sack” Dominican civilians. Haiti imposed a “heavy tribute” on the Dominican people.

Haiti’s constitution forbade white elites from owning land, and Dominican major landowning families were forcibly deprived of their properties. During this time, many white elites in Santo Domingo did not consider owning slaves due to the economic crisis that Santo Domingo faced during the España Boba period. The few landowners that wanted slavery established in Santo Domingo had to emigrate to Cuba, Puerto Rico, or Gran Colombia. Many landowning families stayed on the island, with a heavy concentration of landowners settling in the Cibao region. After independence, and eventually being under Spanish rule once again in 1861, many families returned to Santo Domingo including new waves of immigration from Spain.

Dominican War of Independence (1844–56). In 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte founded a secret society called La Trinitaria, which sought the complete independence of Santo Domingo without any foreign intervention. Duarte, Mella, and Sánchez are considered the three Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic.

In 1843, the new Haitian president, Charles Rivière-Hérard, exiled or imprisoned the leading Trinitarios (Trinitarians). After subduing the Dominicans, Rivière-Hérard, a mulatto, faced a rebellion by blacks in Port-au-Prince. Haiti had formed two regiments composed of Dominicans from the city of Santo Domingo; these were used by Rivière-Hérard to suppress the uprising.

On February 27, 1844, the surviving members of La Trinitaria, now led by Tomás Bobadilla, declared independence from Haiti. The Trinitarios were backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo, who became general of the army of the nascent republic. The Dominican Republic’s first Constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844, and was modeled after the United States Constitution. The decades that followed were filled with tyranny, factionalism, economic difficulties, rapid changes of government, and exile for political opponents. Archrivals Santana and Buenaventura Báez held power most of the time, both ruling arbitrarily. They promoted competing plans to annex the new nation to another power: Santana favored Spain, and Báez the United States.

Threatening the nation’s independence were renewed Haitian invasions. In March 1844, Rivière-Hérard attempted to reimpose his authority, but the Dominicans put up stiff opposition and inflicted heavy casualties on the Haitians. In early July 1844, Duarte was urged by his followers to take the title of President of the Republic. Duarte agreed, but only if free elections were arranged. However, Santana’s forces took Santo Domingo on July 12, and they declared Santana ruler of the Dominican Republic. Santana then put Mella, Duarte, and Sánchez in jail. On February 27, 1845, Santana executed María Trinidad Sánchez, heroine of La Trinitaria, and others for conspiracy.

On June 17, 1845, small Dominican detachments invaded Haiti, capturing Lascahobas and Hinche. The Dominicans established an outpost at Cachimán, but the arrival of Haitian reinforcements soon compelled them to retreat back across the frontier. Haiti launched a new invasion on August 6. The Dominicans repelled the Haitian forces, on both land and sea, by December 1845.

The Haitians invaded again in 1849, forcing the president of the Dominican Republic, Manuel Jimenes, to call upon Santana, whom he had ousted as president, to lead the Dominicans against this new invasion. Santana met the enemy at Ocoa, April 21, with only 400 militiamen, and succeeded in defeating the 18,000-strong Haitian army. The battle began with heavy cannon fire by the entrenched Haitians and ended with a Dominican assault followed by hand-to-hand combat. In November 1849, Dominican seamen raided the Haitian coasts, plundered seaside villages, as far as Dame Marie, and butchered crews of captured enemy ships.

By 1854 both countries were at war again. In November, a Dominican squadron composed of the brigantine 27 de Febrero and schooner Constitución captured a Haitian warship and bombarded Anse-à-Pitres and Saltrou. In November 1855, Haiti invaded again. Over 1,000 Haitian soldiers were killed in the battles of Santomé and Cambronal in December 1855. The Haitians suffered even greater losses at Sabana Larga and Jácuba in January 1856. That same month, an engagement at Ouanaminthe again resulted in heavy Haitian casualties, bringing an effective halt to the invasion.

First Republic. The Dominican Republic’s first constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844. The state was commonly known as Santo Domingo in English until the early 20th century. It featured a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by Article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana on the constitutional assembly by force, giving him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence was over. These privileges not only served him to win the war but also allowed him to persecute, execute and drive into exile his political opponents, among which Duarte was the most important.

The population of the Dominican Republic in 1845 was approximately 230,000 people (100,000 whites; 40,000 blacks; and 90,000 mulattoes).

Due to the rugged mountainous terrain of the island the regions of the Dominican Republic developed in isolation from one another. In the south, also known at the time as Ozama, the economy was dominated by cattle-ranching (particularly in the southeastern savannah) and cutting mahogany and other hardwoods for export. This region retained a semi-feudal character, with little commercial agriculture, the hacienda as the dominant social unit, and the majority of the population living at a subsistence level. In the north (better-known as Cibao), the nation’s richest farmland, farmers supplemented their subsistence crops by growing tobacco for export, mainly to Germany. Tobacco required less land than cattle ranching and was mainly grown by smallholders, who relied on itinerant traders to transport their crops to Puerto Plata and Monte Cristi.

Santana antagonized the Cibao farmers, enriching himself and his supporters at their expense by resorting to multiple peso printings that allowed him to buy their crops for a fraction of their value. In 1848, he was forced to resign and was succeeded by his vice-president, Manuel Jimenes.

After defeating a new Haitian invasion in 1849, Santana marched on Santo Domingo and deposed Jimenes in a coup d’état. At his behest, Congress elected Buenaventura Báez as president, but Báez was unwilling to serve as Santana’s puppet, challenging his role as the country’s acknowledged military leader. In 1853, Santana was elected president for his second term, forcing Báez into exile. Three years later, after repulsing another Haitian invasion, he negotiated a treaty leasing a portion of Samaná Peninsula to a U.S. company; popular opposition forced him to abdicate, enabling Báez to return and seize power.

With the treasury depleted, Báez printed eighteen million uninsured pesos, purchasing the 1857 tobacco crop with this currency and exporting it for hard cash at immense profit to himself and his followers. Cibao tobacco planters, who were ruined when hyperinflation ensued, revolted and formed a new government headed by José Desiderio Valverde and headquartered in Santiago de los Caballeros.

In July 1857, General Juan Luis Franco Bidó besieged Santo Domingo. The Cibao-based government declared an amnesty to exiles and Santana returned and managed to replace Franco Bidó in September 1857. After a year of civil war, Santana captured Santo Domingo in June 1858, overthrew both Báez and Valverde and installed himself as president.

In 1861, Santana asked Queen Isabella II of Spain to retake control of the Dominican Republic, after a period of only 17 years of independence. Spain, which had not come to terms with the loss of its American colonies 40 years earlier, accepted his proposal and made the country a colony again. Haiti, fearful of the reestablishment of Spain as colonial power, gave refuge and logistics to revolutionaries seeking to reestablish the independent nation of the Dominican Republic. The ensuing civil war, known as the War of Restoration, claimed more than 50,000 lives.

The War of Restoration began in Santiago on August 16, 1863. Spain had a difficult time fighting the Dominican guerrillas. Over the course of the war, they would spend over 33 million pesos and suffer 30,000 casualties. In the south, Dominican forces under José María Cabral defeated the Spanish in the Battle of La Canela on December 4, 1864. The victory showed the Dominicans that they could defeat the Spaniards in pitched battle. After two years of fighting, Spain abandoned the island in 1865. Political strife again prevailed in the following years; warlords ruled, military revolts were extremely common, and the nation amassed debt.

After the Ten Years’ War (1868–78) broke out in Spanish Cuba, Dominican exiles, including Máximo Gómez, Luis Marcano and Modesto Díaz, joined the Cuban Revolutionary Army and provided its initial training and leadership.

In 1869, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant ordered U.S. Marines to the island for the first time. Pirates operating from Haiti had been raiding U.S. commercial shipping in the Caribbean, and Grant directed the Marines to stop them at their source. Following the virtual takeover of the island, Báez offered to sell the country to the United States. Grant desired a naval base at Samaná and also a place for resettling newly freed African Americans. The treaty, which included U.S. payment of $1.5 million for Dominican debt repayment, was defeated in the United States Senate in 1870 on a vote of 28–28, two-thirds being required.

Báez was toppled in 1874, returned, and was toppled for good in 1878. A new generation was thence in charge, with the passing of Santana (he died in 1864) and Báez from the scene. Relative peace came to the country in the 1880s, which saw the coming to power of General Ulises Heureaux. “Lilís”, as the new president was nicknamed, enjoyed a period of popularity. He was, however, “a consummate dissembler”, who put the nation deep into debt while using much of the proceeds for his personal use and to maintain his police state. Heureaux became rampantly despotic and unpopular. In 1899, he was assassinated. However, the relative calm over which he presided allowed improvement in the Dominican economy. The sugar industry was modernized, and the country attracted foreign workers and immigrants.

Lebanese, Syrians, Turks, and Palestinians began to arrive in the country during the latter part of the 19th century. At first, the Arab immigrants often faced discrimination in the Dominican Republic, but they were eventually assimilated into Dominican society, giving up their own culture and language. During the U.S. occupation of 1916–24, peasants from the countryside, called Gavilleros, would not only kill U.S. Marines, but would also attack and kill Arab vendors traveling through the countryside.

20th century (1900–30). From 1902 on, short-lived governments were again the norm, with their power usurped by caudillos in parts of the country. Furthermore, the national government was bankrupt and, unable to pay its debts to European creditors, faced the threat of military intervention by France, Germany, and Italy. United States President Theodore Roosevelt sought to prevent European intervention, largely to protect the routes to the future Panama Canal, as the canal was already under construction. He made a small military intervention to ward off European powers, to proclaim his famous Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, and also to obtain his 1905 Dominican agreement for U.S. administration of Dominican customs, which was the chief source of income for the Dominican government. A 1906 agreement provided for the arrangement to last 50 years. The United States agreed to use part of the customs proceeds to reduce the immense foreign debt of the Dominican Republic and assumed responsibility for said debt.

After six years in power, President Ramón Cáceres (who had himself assassinated Heureaux) was assassinated in 1911. The result was several years of great political instability and civil war. U.S. mediation by the William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson administrations achieved only a short respite each time. A political deadlock in 1914 was broken after an ultimatum by Wilson telling the Dominicans to choose a president or see the U.S. impose one. A provisional president was chosen, and later the same year relatively free elections put former president (1899–1902) Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra back in power. To achieve a more broadly supported government, Jimenes named opposition individuals to his cabinet. But this brought no peace and, with his former Secretary of War Desiderio Arias maneuvering to depose him and despite a U.S. offer of military aid against Arias, Jimenes resigned on May 7, 1916.

Wilson thus ordered the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic. U.S. Marines landed on May 16, 1916, and had control of the country two months later. The military government established by the U.S., led by Vice Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp, was widely repudiated by the Dominicans, with caudillos in the mountainous eastern regions leading guerrilla campaigns against U.S. forces. Arias’s forces, who had no machine guns or modern artillery, tried to take on the U.S. Marines in conventional battles, but were defeated at the Battle of Guayacanas and the Battle of San Francisco de Macoris.

The occupation regime kept most Dominican laws and institutions and largely pacified the general population. The occupying government also revived the Dominican economy, reduced the nation’s debt, built a road network that at last interconnected all regions of the country, and created a professional National Guard to replace the warring partisan units. Opposition to the occupation continued, nevertheless, and after World War I it increased in the U.S. as well. There, President Warren G. Harding (1921–23), Wilson’s successor, worked to put an end to the occupation, as he had promised to do during his campaign. The U.S. government’s rule ended in October 1922, and elections were held in March 1924.

The victor was former president (1902–03) Horacio Vásquez, who had cooperated with the U.S. He was inaugurated on July 13, 1924, and the last U.S. forces left in September. In six years, the Marines were involved in at least 370 engagements, with 950 “bandits” killed or wounded in action to the Marines’ 144 killed. Vásquez gave the country six years of stable governance, in which political and civil rights were respected and the economy grew strongly, in a relatively peaceful atmosphere.

During the government of Horacio Vásquez, Rafael Trujillo held the rank of lieutenant colonel and was chief of police. This position helped him launch his plans to overthrow the government of Vásquez. Trujillo had the support of Carlos Rosario Peña, who formed the Civic Movement, which had as its main objective to overthrow the government of Vásquez.

In February 1930, when Vásquez attempted to win another term, his opponents rebelled in secret alliance with the commander of the National Army (the former National Guard), General Rafael Trujillo. Trujillo secretly cut a deal with rebel leader Rafael Estrella Ureña; in return for letting Ureña take power, Trujillo would be allowed to run for president in new elections. As the rebels marched toward Santo Domingo, Vásquez ordered Trujillo to suppress them. However, feigning “neutrality,” Trujillo kept his men in barracks, allowing Ureña’s rebels to take the capital virtually uncontested. On March 3, Ureña was proclaimed acting president with Trujillo confirmed as head of the police and the army. As per their agreement, Trujillo became the presidential nominee of the newly formed Patriotic Coalition of Citizens (Spanish: Coalición patriotica de los ciudadanos), with Ureña as his running mate.

During the election campaign, Trujillo used the army to unleash his repression, forcing his opponents to withdraw from the race. Trujillo stood to elect himself, and in May he was elected president virtually unopposed after a violent campaign against his opponents, ascending to power on August 16, 1930.

Trujillo Era (1930–61). Rafael Trujillo imposed a dictatorship of 31 years in the country (1930–1961). There was considerable economic growth during Rafael Trujillo’s long and iron-fisted regime, although a great deal of the wealth was taken by the dictator and other regime elements. There was progress in healthcare, education, and transportation, with the building of hospitals, clinics, schools, roads, and harbors. Trujillo also carried out an important housing construction program, and instituted a pension plan. He finally negotiated an undisputed border with Haiti in 1935, and achieved the end of the 50-year customs agreement in 1941, instead of 1956. He made the country debt-free in 1947. This was accompanied by absolute repression and the copious use of murder, torture, and terrorist methods against the opposition. It has been estimated that Trujillo’s tyrannical rule was responsible for the death of more than 50,000 Dominicans.

Trujillo’s henchmen did not hesitate to use intimidation, torture, or assassination of political foes both at home and abroad. Trujillo was responsible for the deaths of the Spaniards José Almoina in Mexico City and Jesús Galíndez in New York City.

In 1930, Hurricane San Zenon destroyed Santo Domingo and killed 8,000 people. During the rebuilding process, Trujillo renamed Santo Domingo to “Ciudad Trujillo” (Trujillo City), and the nation’s – and the Caribbean’s – highest mountain La Pelona Grande (Spanish for: The Great Bald) to “Pico Trujillo” (Spanish for: Trujillo Peak). By the end of his first term in 1934 he was the country’s wealthiest person, and one of the wealthiest in the world by the early 1950s; near the end of his regime his fortune was an estimated $800 million ($5.3 billion today).

Trujillo, who neglected the fact that his maternal great-grandmother was from Haiti’s mulatto class, actively promoted propaganda against Haitian people. In 1937, he ordered what became known as the Parsley Massacre or, in the Dominican Republic, as El Corte (The Cutting), directing the army to kill Haitians living on the Dominican side of the border. The army killed an estimated 17,000 to 35,000 Haitian men, women, and children over six days, from the night of October 2, 1937, through October 8, 1937. To avoid leaving evidence of the army’s involvement, the soldiers used edged weapons rather than guns. The soldiers were said to have interrogated anyone with dark skin, using the shibboleth perejil (parsley) to distinguish Haitians from Afro-Dominicans when necessary; the ‘r’ of perejil was of difficult pronunciation for Haitians. As a result of the massacre, the Dominican Republic agreed to pay Haiti US$750,000, later reduced to US$525,000.

During World War II, Trujillo symbolically sided with the Allies and declared war on Japan the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor and on Nazi Germany and Italy four days later. Soon after, German U-boats torpedoed and sank two Dominican merchant vessels that Trujillo had named after himself. German U-boats also sank four Dominican-manned ships in the Caribbean. The country did not make a military contribution to the war, but Dominican sugar and other agricultural products supported the Allied war effort. American Lend-Lease and raw material purchases proved a powerful inducement in obtaining cooperation of the various Latin American republics. Over a hundred Dominicans served in the American armed forces. Many were political exiles from the Trujillo regime.

Trujillo’s dictatorship was marred by botched invasions, international scandals and assassination attempts. 1947 brought the failure of a planned invasion by leftist Dominican exiles from the Cuban island of Cayo Confites. July 1949 was the year of a failed invasion from Guatemala, and on June 14, 1959, there was a failed invasion at Constanza, Maimón and Estero Hondo by Dominican rebels from Cuba.

On June 26, 1959, Cuba broke diplomatic relations with the Dominican Republic due to widespread Dominican human rights abuses and hostility toward the Cuban people.