Capital. San Salvador

Official languages. Spanish

Ethnic Groups. 86.3% Mestizo (mixed White and Indigenous), 12.7% White, 0.2% Indigenous, 0.1% Black, 0.7% Other

Relgion. 84.1% Christianity, 44.9% Roman Catholicd, 37.1% Protestant

2.1% Other Christian, 15.2% No religion, 0.7% Other

Area. 21,041 km2 (8,124 sq mi) (148th)

GDP (PPP). $8,388 (111th)

GDP (nominal). $4,041 (111th)

Gini. 38.8 medium

Currency. United States dollar (USD; since 2001 with 1$, 25 and 10¢ coins), Bitcoin (BTC, XBT; since September 2021)

Calling code. +503

Covid. No rules. Most everyone wears a mask, even outdoors. Masks are required for entry to most businesses but hand sanitizer is not required.

Observations – El Salvador

1. People. They uniformly appear “mestizo” a mix of European (primarily Spanish) and indigenous people. They tend to be short and overweight. Most appear to make a livelihood in the itinerant selling industry – vegetables and fruit in markets and along highways.

2. Roads. The highways are of high quality with much appearing to be new pavement. Most have shoulders. Freeways connect the major areas. The roads leading into the major centers of Santa Ana and San Miguel are two-lane and clog up easily.

Gas is $4.15/US gallon (very cheap). Speed limits are generally 80km/hour and occasionally 90 but there are no speed traps and I often drove well over the limit, even through towns – all depending on traffic.

3. Drivers. As always there are a few crazy speed freaks but not many here. Most drive well but pay no attention to the speed lanes of 4-lane highways. There are many slow vehicles that hold up traffic and passing on 2-lane roads can be challenging, especially as many drivers are cautious creating long lines.

4. Cicadas. With a life cycle of every 11 or 17 years, I passed through many isolated areas with a loud whining sound, just like cicadas.

5. Get Around. Old Blue Bird buses are the norm between towns. However many travels in open trucks from small to large. There are no seats and all stand or sit in precarious places on the box sides. I wonder how many people die in accidents in these? It appears very dangerous.

EL SALVADOR – WEST (San Salvador, Santa Ana, West of River Lempa) Mar 31-April 5, 2022

Day 1

My original plan was to finish seeing all the countries in the Caribbean, but flying between Haiti, Jamaica, the Bahamas, and St Vincent is cumbersome as all go through Ft Lauderdale. I also didn’t think I could navigate the Covid rules of the Bahamas or St Vincent. So I decided to go to El Salvador, my last country in Central America. The flight was from Port au Prince on JetBlue to Ft Lauderdale, then on Spirit to San Salvador on Sprint for CAD$272, a very good deal.

The US Covid rules make little sense. If someone had a positive test within 90 days, they still must have a Doctors’ note stating recovery. I saw this in the IATA info but hoped I could get away with it. They wouldn’t let me board so I had to have an antigen test at the airport in Haiti for $85.

I arrived at 02:30 (the Spirit flight was late). The airport is 43 km from San Salvador and Uber and taxis are uncommon at this time of night. My incredible luck struck again. Sitting across the aisle was a young woman from Washington DC who had arranged a driver – and we were staying at the same hostel (La Zona)! The ride was $30 split between the two of us. The hostel is open 24 hours and I was soon tucked into bed.

SAN SALVADOR

I have been having difficulties with Google Maps as I keep losing my waymarks so spent most of the morning sorting things out. I then had a walk and bus about seeing most of the NM sites in the city. I was able to get a SIM card near the hostel but still never had data all day. With offline maps, I was able to easily find my way. I eventually resorted to using MapsMe.

Get around. There are no share vans but an extensive bus network at 25 cents a ride. I could not figure out the bus’s destination so jumped on any bus going in the right direction and got off if it turned. At 25 cents, it was cheap. However, at the end of the day, I had great difficulty getting back to my hostel and traveled the same route three times before I realized I had to return to the Cathedral area.

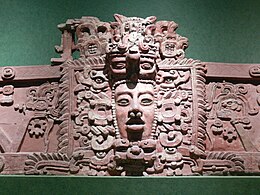

National Museum of Anthropology David J. Guzman. Opened in 1883, learn the history of El Salvador and its people. In five halls, see the treasures and ancient artifacts of pre-Columbian settlers, from the Maya and Olmec to Pipil tribes who inhabited the jungles and coasts. See the agriculture, human settlements, religion (ancient altar of stone and petroglyphs), arts, trade, and traditional Salvadoran crafts, $10

Mercado Nacional de Artesanias. Many shops sell knick-knacks, traditional woven cloth, and clothing.

Forma Museum. An art museum with a gallery of contemporary art (not interesting) to the permanent collection with some nice pieces. The best thing here is the lovely building. Free

Monumento al Divino Salvador del Mundo. This religious monument sits in the middle of a huge roundabout. It sits on a tall plinth with a glove and a relatively small Christ on top.

The next two are in a nice large park.

Memory and Truth Monument. In the NM The Dark Side series, this is a long wall of black granite engraved with nearly 30,000 names, a roll of dead and disappeared from the civil war between leftist guerrillas and the right-wing military government which ended in 1992. It is incomplete. Officially, 75,000 died and thousands more are missing. Not all the names of the war’s victims were available when the monument project began, so the list is growing. An engraved name is often the closest thing to a gravesite many people will have.

Museum of Children’s Tin Marin. Really only for kids, this offers both fun and education – a butterfly garden, paint a car, act in a play at the theater, or go to the library and read about what interests you. Learn about science, medicine, transportation, outer space, the human body, and more.

A guide is required and English tours are only available on Thursdays and Sundays. The administrator was called and I was allowed to see it without a guide. $3

The following are downtown.

Mercado Central. Metal girders support a corrugated metal roof in the gigantic market. It has everything from wedding dresses to food. Surrounding the market for a few blocks are stalls with produce and food.

Cathedral of San Salvador. It was originally not open except for the crypt with large paintings showing the Ways of the Cross. After my bus confusion at the end of the day, I returned. The church is vented with lovered panes of coloured glass. Four large paintings back the altar. The ceiling is coffered wood.

Currency Museum (Museo Y Biblioteca Luis Alfaro Duran). Shows banknotes, coins, equipment, documents and photographs. paintings, sculptures, and a 30,000 volume library. It is named after the first president of the Central Reserve Bank (BCR) Free

Iglesia El Rosario. This unusual church was built in 1962 replacing older churches. It is a parabolic half circle 90m long, 35m wide and 23m high. The outside is rough reinforced concrete. The entire curve has 25 rows of coloured glass making for a lovely church. The altar side is red brick. The back wall is vented and has a lovely 2-foot high band of metalwork. $2

Military Museum of the Armed Forces of El Salvador. Outside are armoured vehicles. Several small rooms with weapons, many photographs, uniforms, and other uninteresting things. Inside the courtyard are 3 old planes and 2 helicopters. Free

Natural History Museum. The usual stuffed birds and not great dioramas. $2

Museum of Natural History. The usual stuffed birds and animals, and rocks. A lot of information on volcanoes. $3

National Zoo Park. Sitting in a very large space with many mature trees and a river running through it, this park has lions, Bengal tigers, jaguar, puma, ocelot, deer, monkeys, tapir, zebra, reptiles, and many birds. Access is on the NE corner. $2

After the zoo, I had bus confusion and finally returned to the cathedral area to find a bus going my way to my hostel.

Day 2

I was going to rent a car today and start a 3-day drive around ES, but Google Maps has crashed. I saw only these two places, both near my hostel, and basically took the day off.

Museum of Art of El Salvador. In a lovely new building, there was a lot of great photography and above-average art for a modern art museum but covered time from about 1900 to the present. $5

Monumento a la Revolucion. Commemorating the revolution of 1948, this was inaugurated in 1954. It is huge standing 25 m tall in the shape of a half curve. Made of reinforced concrete, the face has a mosaic with a man holding his arms upstretched.

Day 3

I rented a car (Inter Car $30/day + $15 to return to airport) and then drove it to my hostel. I then started a bid drive about through all of El Salvador over 3 days.

El Boquerón NP is located on top of the San Salvador Volcano at 5,905 feet (1800 meters) the park’s main attraction is a crater five kilometers in diameter and 558 meters deep. In addition, there is a small crater within the crater named “Boqueroncito” (little Boquerón). El Boquerón has a cool temperate climate year-round.

The park is home to many plant species identified as ornamentals such as “cartuchos”, hydrangeas, begonias, and wild “sultanas”. There is wildlife such as armahiiiidillos, raccoons, deer, and foxes.

The park features a visitors’ centre and short hiking trails up the side and along the rim of the crater.

Joya de Cerén Archaeological Site WHS is a pre-Hispanic farming community that, like Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy, was buried under an eruption of the Laguna Caldera volcano c. AD 600. Because of the exceptional condition of the remains, they provide an insight into the daily lives of the Central American populations who worked the land at that time.![]() Joya de Cerén Archaeological Site © Colinmac

Joya de Cerén Archaeological Site © Colinmac

The area was abandoned until the ash layer had weathered into fertile soil and the Joya de Cerén settlement was founded. Not long afterward, it was destroyed by the eruption of the Loma Caldera. The site was discovered during the construction of grain-storage silos in 1976, when a clay-built structure was exposed by a bulldozer.

The circumstances of the volcanic event led to the remarkable preservation of architecture and the artifacts of ancient inhabitants in their original positions of storage and use. It is the best-preserved example of a pre-hispanic village in Mesoamerica. 18 structures have been identified, all made of earth with thatch roofs: a large community (public) building on the side of a plaza, two houses of habitation that were part of domiciles, three storehouses, one kitchen, and a sweat bath. Rammed earth construction was used for the public buildings and the sauna, and wattle and daub (which is highly earthquake resistant) for household structures.

The degree of preservation also applies to organic materials, from garden tools and bean-filled pots to sleeping mats, animal remains, and religious items that normally deteriorate in tropical conditions and were part of the subsistence and daily life of the inhabitants. These have been preserved as carbonized materials or as casts in the ash deposits. Several cultivated fields containing young and mature maize plants, a garden with a variety of herbs and a henequen (agave) garden, guava and cacao, have also been found.

This site is remarkable by virtue of the completeness of the evidence that it provides of everyday life in Mesoamerican farming community of the seventh century A.D, which is without parallel in this cultural region.

Don’t miss the museum with great displays and a wonderful selection of well-painted pottery. The archaeological site is covered with 3 large metal-roofed buildings. The buildings have elaborate rammed earth walls. It is interesting to see the 14 layers of ash 3-5 m thick as part of all the excavations. $11

Caldera De Coatepeque is a volcanic caldera formed during a series of rhyolitic explosive eruptions between about 72,000 and 57,000 years ago. Since then, basaltic cinder cones and lava flows formed near the west edge of the caldera, and six rhyolitic lava domes have formed. The youngest dome, Cerro Pacho, formed after 8000 BC.

Lake Coatepeque is a large crater lake in the east part of the Coatepeque Caldera. There are hot springs near the lake margins. At 26 square kilometres (10 sq mi), it is one of the largest lakes in El Salvador. In the lake is the island of Teopan, which was a Mayan site of some importance.

SANTA ANA (pop 375,000) is the second-largest city in El Salvador 64 kilometers northwest of San Salvador. A major processing center for El Salvador’s sizable coffee bean industry is located near Santa Ana. Santa Ana has become a tourist destination, especially for tourists eager to learn about Salvadoran culture and traditions.

The city of Santa Ana is located on a meseta about 665 meters above sea level. The city has a year-round warm climate with an average temperature of around 25 °C (77 °F). The main river is the Guajoyo river, a major tributary of the much larger Lempa River. There is a major Hydroelectric Power station at the Guajoyo river that provides electricity to most of the western sector of the country.

The city is situated among a number of green hills, including Tecana Hill and the Hills of Santa Lucía. In the southern part of the municipality is the Ilamatepec volcano, the highest volcano in the country, which had a moderate eruption in 2005 that killed two people. Close to it is another famous volcano, Izalco, known to sailors throughout the mid-19th century and early 20th century as “The lighthouse of the Pacific” due to its constant eruptions.

History. The city of Santa Ana has a pre-Columbian origin that was depopulated by the eruption of Lake Ilopango at 250 DC. The city was founded by the Maya Poqomam in the classical period in 1200.

The town was conquered by the Spanish between 1530 and 1540. In 1894, a revolution that would overthrew President Carlos Ezeta, who had ruled the country as de facto dictator occurred. Since then, the town earned the nickname of “the heroic city” as the 44 rebels who led the revolution were from the municipality.

In the so-called “golden age of coffee” in El Salvador, Santa Ana was the most prosperous city in the country,

During the civil war in El Salvador (1980–1992), the municipality of Santa Ana was also affected by armed conflict, which led to the emigration of many residents of the city. After the war, Santa Ana and all of El Salvador began to address the problem of rising crime rates, mostly due to the existence of “maras” or gangs, mainly generated by the deportation of illegal immigrants from the United States.

Economy. The main economic engines of the city are in retail and manufacturing. In the north and west of the city are factories and assembly plants mostly of foreign origin. The southern part of the city is more commercially developed, containing many restaurants, commercial banks, hotels and shopping malls.

Santa Ana has two main markets: the Colón and Central Markets, only a few streets from one another, offering a great variety of products.

The city has many old buildings such as: Catedral de Santa Ana (The Cathedral of Saint Anne), Alcaldía Municipal de Santa Ana (Santa Ana City Hall) and the Teatro de Santa Ana (Santa Ana Theater).

Museo Regional del Occidente. In a grand old bank building is the main municipal museum with a large collection of archaeological and contemporary history pieces, a library, a cafeteria and a permanent exhibition on the History of La Moneda in El Salvador. $2 Note that it closes over noon.

Santa Ana Cathedral. (Catedral de la Señora Santa Ana), is a neo-Gothic cathedral built between 1902-1906. The marble altar of the image of Saint Anne was added in 1960.

Neo-Gothic cathedral, it has three naves, 122 m long and 22 m wide, the lateral naves eight meters wide. Each tower has 3 bells made in Holland.

With a very ornate facade of balconies and spires, this is a lovely church inside. Very long and narrow, the arches are pointed, columns red and green and altar backed by a white spired “thing”. Many of the polychromes in the side altars were draped with cloth. I entered during a service on a Sunday, and the church was relatively crowded.

I ate in Santa Ana and continued on to Lake Guija for the night.

Lake Guija Tentative WHS (21/09/1992). Shared with neighboring Guatemala, it is one of the largest natural lakes in the region preserving an outstanding natural environment – a large forest on San Diego Volcano and an area of marshland and ponds extending north of the lake (the “Lagunas de Metapan”). A traditional fishery still exists.

Over 20 archaeological sites have been recorded in the lakes environs, including a Late Preclassic settlement (400 BC- 200 AD), several Postclassic mound groups (900-1550 AD), and an early Colonial church ruin. Some well-preserved architecture but none have been professionally excavated.

I drove from Santa Ana 33 km to the shore of Lake Guija and camped for the night. Unfortunately, two of the car windows did not roll down so ventilation was not as good as needed. I finally opened the door. There were no bugs.

At about 8:30, the police arrived. I refused to open the door and asked if there was a problem? They said no, so I told them to leave me alone, and they left. I had a lovely sleep with no mosquitos.

San Diego La Barra Forest is a dry tropical forest just south of Lake Guija.

Day 5

The drive into Santa Ana was a traffic nightmare. I drove on the wrong side and some side streets and was able to bypass a lot.

Chalchuapa Tentative WHS (21/09/1992). Divided into two sites.

Archaeological investigations have demonstrated that the present town of Chalchuapa has at least 3200 years of continuous human occupation. There are several groups of monumental architecture relating to different periods of the community’s prehistory. Three of these groups are currently protected, including the two Late Preclassic (400 BC – 200 AD) of El Trapiche and Casa Blanca, and the Classic to Early Postclassic Tazumal group (200 – 1200 AD). Two monumental Olmec sculptures from Chalchuapa are the southernmost examples known in Mesoamerica. Chalchuapa is considered to have been an outstanding center of Late Preclassic times.

Chalchuapa also possesses important examples of architecture from the Colonial and Republican periods. There is a small volcanic Lake Cuscachapa.

Sitio Arqueoogico Casa Blanca. The main and largest site. $5.

El Tazumal. $5

I had a typical breakfast of beans, eggs, and half a large avocado in Chalchuapa.

Salto El Cubo. This was on the way but the last 5.7 km off the highway was a disastrous road. I didn’t go.

The next 3 sites are on the Ruta de las Flores, a drive through a very hilly area, but with a great road.

Concepción de Ataco. NM Villages and Small Towns series. A nice market full of produce, a lovely central square with a gazebo, big trees, tables and benches (where I am sitting now writing this), the church Ava Maria (gorgeous with polychromes in lovely elevated wood cases and.a wood arched ceiling and many murals.

Apaneca. NM Villages and Small Towns series. Very quiet and not nearly as busy as Concepcion, it has a large white colonial church (not open), and a small square with a monstrous tree.

Juayúa. NM Villages and Small Towns series. A very active town on a Monday with an active veg market, square (small, lovely, a running fountain, many trees, benches and people, stores, knick-knack market, and a big white/red trim church (closed but two levels of stained glass).

Los Chorros (7 waterfalls). Very near the town of Juayua, maps show two routes. The first was a long 2.8 km walk (along the river and uncertain if even doable) or the right way: a short drive some on dirt and then deal with the family that controls access. $2 to park (he didn’t have change for a five so told me to drive down) but I parked just outside their “lot”. The dirt road is rough and the steep section paved but I doubt that my underpowered car could handle coming back up. He said a 20-minute walk but it was more like 10 minutes. Then arrive at a locked gate (signed by a hydroelectric company) and a nive stone walkway down to the falls. A tour arrived and a woman from above appeared behind the gate and unlocked it but said I would have to pay $10. From outside the gate, I could see the creek, the bottom of one fall and hear them. I left.

Cerro Verde (Los Volcanes) NP. A volcano located in the Apaneca mountain range. 2030 meters high, its crater is eroded and covered by a thick cloud forest. It is estimated that its last eruption was 25 thousand years ago.

It has viewpoints of the volcanoes of Santa Ana, Izalco and Lake Coatepeque, as well as an orchid garden, a walk through the forest and climbs to the Izalco Volcano (height 1,980 meters above sea level) and to the Santa Ana Volcano (height 2,381 meters above sea level). The park also has three recreational trails: Las Flores Misteriosas, Ventana a la Naturaleza and Antiguo Hotel de Montaña. The walks to the summits of Izalco and Santa Ana must be done in the company of local guides

More than 125 species of trees in a Tropical Evergreen Broadleaf High Mountain Forest: wax sticks, pinabete, sapuyulo or lava species such as lichens, clubmosses, grasses and agaves; orchids of different species and bromeliads known as gallitos. A unique species has broad, flattened and soft leaves due to the presence of hairs. It is adapted to sulfurous gases and strong winds. There are approximately 134 hectares of cypress plantations that were introduced by the former owners.

The mammals are: coyotes, spiny fox, deer, ocelots. Birds: short-tailed hawk, mountain falcon and black eagle among others.

It has two visitor centers in the San Blas and Los Andes sectors, camping areas, viewpoints and hiking trails that lead to the volcanic crater. The climate is cool, on average around 6ºC to 8ºC and 16ºC to 24ºC in May to October it rains copiously. Access to the summits of the three volcanoes is allowed in the Park .

The three entrances are: 1. The Cerro Verde Sector, 2. The San Blas Sector and 3. The Los Andes Sector, 6.5 km along a dirt road (4×4 required) from the Carretera a Cerro Verde (8.4 kilometers after the detour),

Sonsonate. (pop 71,541. On the Sensunapan River and the Pan-American Highway from San Salvador to the Pacific port of Acajutla, 21 km south.

Historically, the area was a producer of cotton. Most of the cotton produced, as of 1850, was retained for local use. Today, tobacco farming, cattle ranching and tourism (volcanos, coral reef) are important industries.

I stopped by the main square with its 4 fountains. Across the street is the cathedral, totally white outside and in, it has three unusual metal “sleds” holding large wood effigies.

Cara Sucia / El Imposible Tentative WHS (21/09/1992). Combining cultural and natural characteristics, its archaeological record extends to 166 BC, with some of the earliest evidence for agricultural settlements in southern Mesoamerica. During the Late Classic Period (600-900 AD), a regional center of the Cotzumalhuapa culture was located here, being the easternmost extension of this ethnic group. These and other prehistoric peoples exploited the rich natural resources available from the highly varied environment compressed into a narrow coastal fringe, including sand beaches, mangrove forests, alluvial plains, and volcanic highlands. Unusually for a Tentative WHS, there is no archaeological site.

El Imposible NP. The highland sector (El Imposible) preserves the largest extant forest in El Salvador.

I then drove along the Pacific coast. The road occasionally follows very close to the coast but there are high cliffs with the only viewpoints at restaurants (all with thatched roofs).

El Tunco is a tiny off-the-beaten-path beachside town with only two streets, Backpackers and surfers come for the nightlife and legendary surfing. El Tunco means “The pig” referring to a huge ocean rock that used to look like a pig.

There is no sand beach but a steep, large black cobble that shifts with the surf;  El Tunco is famous for its surfing. At the west end is a rocky right-hand pointbreak called Sunzal, and in the east, there’s Bocana a stronger left.

El Tunco is famous for its surfing. At the west end is a rocky right-hand pointbreak called Sunzal, and in the east, there’s Bocana a stronger left.

The caves are big amphitheatres you can walk through and are accessible at low tide, To get to the caves walk left over rocks for about ten minutes.

La Libertad beaches. About 7 km from El Tunco, they are also famous for surfing. Catch buses that come every 10-15 minutes (25 cents). See the boats being hauled using ropes and pulleys. It is a good place to buy groceries as El Tunco is expensive.

Tamanique Waterfalls. The way isn’t clear and the path is steep with exposed roots and loose stones. The return journey requires a rope to pull yourself up the cliff. Hire a guide from any shop in El Tunco for $US10 per person for groups of 3-4 or $US20 if you do it on your own. There’s a twelve-meter high cliff jump. Everyone goes to the beach at sunset. See friends, play frisbee, and have that last dip in the ocean.

Everyone goes to the beach at sunset. See friends, play frisbee, and have that last dip in the ocean.

Costa del Sol. About 58 km east of La Libertad, public beaches are difficult to access as most are private related to resorts. The road follows high concrete walls with large metal gates for many miles. Most appear private but there are some large resorts including Costa del Sol. Only one hotel had an open gate – a gorgeous hotel for $85.

I ended up staying at the only hotel on the landside – the Real Costa Inn – with perfectly acceptable rooms and a great deal for $25 per night. It appeared I was one of the only guests.

The next morning I found beach access. Costal del Sol is a deep, grey sand beach that stretches for miles as far as one can see. There was big surf.

Day 6

I was up early on my way to San Miguel in El Salvador East.

I didn’t see the following in El Salvador West:

World of Nature

Cerrón Grande Dam Wetlands

Montecristo NP

Rancho Grande or El Junquillo Forest

Villages and Small Towns: Jayaque

Waterfalls. Malacatiupan Hot Spring Waterfalls

Lakes: Lake Ilopango

==============================================================

EL SALVADOR – EAST (San Miguel, La Union, East of River Lempa) April 5, 2022

Casa Del Escritor Alberto Masferrer, Usulutan. In the House and Biographical Museums, Masferrer (1868-1932) was a Salvadoran essayist, philosopher, fiction writer, and journalist, best known for the development of the philosophy of ‘vitalismo’. He was born in Alegría, Usulután formerly Tecape, Usulután on 24 July 1868. He did not receive a formal education, instead claiming to have been educated by “the university of life,” but he did travel widely, having lived in several Central American countries, as well as in Chile, New York, and several European nations. During his public career at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of El Salvador, he served as an ambassador of El Salvador in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Belgium, and served as a professor in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Chile, and Argentina. Having served in the government of President Arturo Araujo, he was sent into exile in Honduras by the dictatorship of Maximiliano Hernández Martínez following the uprising of 1932 known as the 1932 Salvadoran peasant massacre, dying that same year on 8 September in the city of Tegucigalpa. He was well respected during his life, having earned the praise of such major Salvadoran figures as Arturo Ambrogi, Miguel Ángel Espino, Claudia Lars, and Salarrué.

SAN MIGUEL (pop 518,000) is a city 138 km east of San Salvador, the country’s third most populous city.

It was established in 1530, as a bastion for the conquest of the Lenca kingdom of Chaparrastique. In 1655, a volcanic eruption almost destroyed the entire city and only an image of Mary in the parish church was spared.

It is an important center for agriculture, textile and chemical industries

In November, San Miguel celebrates its municipal festivities in honor of “Nuestra Señora De La Paz” (Our Lady of Peace), the San Miguel Carnival being the final and main event that takes place on the last Saturday of the month with 1,000,000 people attending it for its 50th anniversary. It is considered the biggest entertainment, music and food festival in El Salvador and one of the largest in Central America.

San Miguel is famous for its nightlife along Roosevelt Avenue, the main thoroughfare that slices the city in half. One of those halves includes places of historical interest such as the Cathedral of “Nuestra Señora de la Paz” (1862), Guzman Park, and Francisco Gavidia Theater (1909), and the Palacio Municipal (1935).

Museo Regional del Oriente. Exhibits on East Salvadorian cultural heritage with the usual for a regional museum: archaeology, ethnography, and history. $3

San Miguel Cathedral. Near the square, the layout of this 3-nave church is unusual as there are no columns making for a wide-open church.

I then returned to El Salvador West.

SENSUNTEPEQUE*

Iglesia Nuestra Señora del Pilar. A nice 3-nave church but has a new odd ceiling. It is well ventilated with louvers and stained glass windows that open. It sits on the square near the tower.

Torre de San Vicente, Built in 1929-30, it stands 40m tall. It withstood the earthquake of December 19, 1936, another on January 13, 2001, but not the earthquake of February 13, 2001 a month later, The tower was badly damaged and had to be demolished to be rebuilt at a cost of 1 million dollars including the new clock. The original clock was German but this one came from Mexico. It chimes on the hour and is preceded by music.

This unusual clocktower is a white wedding cake with 6 levels. Normal stairs access the first big area and a spiral staircase (closed) goes up the middle. It is in the middle of the main square.

Ciudad Vieja / La Bermuda Tentative WHS (21/09/1992) Founded in 1525 as Villa in the Valle de la Bermuda, but not occupied until 1528 due to resistance from the natives, they set about pacifying, dominating, Christianizuing and Castilianize the natives.

The town has more characteristics of a military fort than of a proper city. It was abandoned around 1545 to move to present-day San Salvador in the Valle de las Hamacas. Rediscovered in the 20th century, it is one of the few places in Latin America from the time of the Conquest of America and the first decades of colonization. The site is located some ten kilometers south of Suchitoto.

Santiago, Guatemala, founded in July 1524 was the first city founded by Spain and the second. Located at the foot Tecomatepe hill on the El Molino river, it still maintains its grid layout, with streets that start from the main square. When abandoned in 1545, the buildings were dismantled and were never subsequently built upon, so the foundations were preserved.

There may have been seventy families of encomenderos, mostly with mestizo children and indigenous people.

The last 1.5kms was on an extremely rough road and was not worth the effort. I doubt it gets many visitors.

SUCHITOTO. (pop 24,786 – 7,654 urban and 17,132 people in the rural communities). This is one of the prettiest small towns in the world – cobbled streets, well cared for pastel homes, and a lovely church, very long and narrow with wood columns, blue altar cases, and a wooden altar. It should apply for WHS status.

On the 1980-92 civil war in El Salvador, the population of Suchitoto decreased from 34,101 people in 1971 to 13,850 by 1992. It has become an important tourist destination due to its well-conserved colonial architecture and cobblestone roads, hostels, restaurants, arts and cultural spaces.

Casa De Alejandro Cotto. In the NM House and Biographical Museums series, this is a wonderful U-shaped house (bedroom, chapel, dining room and kitchen don’t have exhibits) surrounding a not to be missed garden. Cobble paths surround raised beds, a pool, fountain and descend to a viewpoint with the entire Lake Suchitoto spread out below it.

There are two waterfalls near town that I didn’t see: Cascada Los Tercios-Suchitoto and Salto El Cubo

The road to Cihuatan was hard to find in Sochitoto, but it is a fast 23 km drive here.

Cihuatán is a major pre-Columbian archaeological site and a very large city located in the extreme south of the Mesoamerican cultural area and has been dated to the Early Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology (c. 950–1200 AD).

Cihuatán was established in the 8th or 9th century AD with occupation not lasting more than a century or so. The founding of the city coincides with the abandonment of major Maya Classic period cities in Honduras. It was destroyed by a massive fire.

Ceramics excavated at Cihuatán include large locally-produced ceramic effigies of central Mexican deities such as Tlaloc and Xipe Totec, locally-produced utilitarian ceramics, obsidian artifacts

The city had two principal ceremonial centres: the Western Ceremonial Centre includes a large pyramid, platforms that originally supported superstructures, and two Mesoamerican ballcourts. The Eastern Ceremonial Centre has a residential cluster and the main marketplace.

I then returned to San Salvador and stayed again at La Zona Hostel.

I then had a decision to make – whether to return home or continue traveling to finish South America (Paraguay is my last country in South America and I wanted to see the rest of Brazil, especially Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo). Finishing S America would be a huge relief to eliminate one isolated country from my list. I also have nothing pressing to do at home. I am tired after another long 9+ months of travel but my drive and curiosity keep me going.

I booked a relatively cheap flight to Asuncion on Avianca/Copa via Quito Ecuador and Panama City ($CAD 591, 23+ hours) and a great hostel in Asuncion (Nomada Hostel, $11 per night, rated 9.3) close to the city center.

I had to return the car to the airport by 1 pm so had a wait in the airport of over 8 hours (added to my 7 and 5-hour layovers in Ecuador and Panama).

I didn’t see the following in Salvador East:

SE of San Miguel:

Playa El Cuco

Lake Olomega

North of San Miguel:

Cacaopera Tentative WHS (21/09/1992) Cacaopera is the sole surviving traditional community representative of an otherwise vanished ethnic group thought to have come from Nicaragua in the 5th-7th centuries.

The marked traditionalism of Cacaopera is attributed to its isolation within very mountainous terrain. The region was severely affected by the war and many of the inhabitants of outlying hamlets relocated to Cacaopera. Cacaopera was alternatively occupied by Army and FMLN troops, and was the scene of firefights and bombardments. These circumstances introduced considerable changes in traditional lifeways.

The area has numerous archaeological sites, including rock shelters with petroglyphs, pictographs and stone tools. The archaeological site of Xualaka is considered to have been the dominant and main site; while Yarrawalaje, Siriwal, and Unamá Cave were ceremonial centers.

Espiritu Santo Cave, Corinto

Next to the north Honduras border:

Museum of the Revolution, Perquin

Llano del Muerto in Ciudad Barrios

In the far east:

Gulf of Fonseca Tentative WHS (21/09/1992).Gulf region with a wide variety of well preserved coastal environments, including islands, mangrove forests, sand beaches, and rock cliffs with rich flora and fauna. In the prehispanic past, there was a dense human settlement on its islands and mainland fringes, with over 10 major sites usually shellmounds of mollusks that accumulated layer by layer. Dates range from 1850 BC to the colonial period. There are mound groups and ruins of early colonial churches. Facing the onslought of pirates, the Lenca community situated on islands was abandoned by the late 17th century. There remains traditional fishing and gathering of molluscs and crustaceans.

Conchaguita and Meanguera del Golfo (beaches) are islands in the gulf. El Icacal Beach and Maculis Beach are near the Gulf.

The Goascorán River forms the east border with Honduras.

========================================================

EL SALVADOR GENERAL

El Salvador (“The Saviour”), is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador’s capital and largest city is San Salvador. The country’s population in 2021 is estimated to be 6.8 million.

Among the Mesoamerican nations that historically controlled the region are the Lenca (after 600 AD), the Mayans,] and then the Cuzcatlecs. Archaeological monuments also suggest an early Olmec presence around the first millennium BC. In the beginning of the 16th century, the Spanish Empire conquered the Central American territory, incorporating it into the Viceroyalty of New Spain ruled from Mexico City. However the Viceroyalty of Mexico had little to no influence in the daily affairs of the isthmus, which was colonized in 1524. In 1609, the area was declared the Captaincy General of Guatemala by the Spanish, which included the territory that would become El Salvador until its independence from Spain in 1821. It was forcefully incorporated into the First Mexican Empire, then seceded, joining the Federal Republic of Central America in 1823. When the federation dissolved in 1841, El Salvador became a sovereign state, then formed a short-lived union with Honduras and Nicaragua called the Greater Republic of Central America, which lasted from 1895 to 1898.

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, El Salvador endured chronic political and economic instability characterized by coups, revolts, and a succession of authoritarian rulers. Persistent socioeconomic inequality and civil unrest culminated in the Salvadoran Civil War from 1979 to 1992, fought between the military-led government backed by the United States, and a coalition of left-wing guerrilla groups. The conflict ended with the Chapultepec Peace Accords. This negotiated settlement established a multiparty constitutional republic, which remains in place to this day.

While this Civil War was going on in the country large numbers of Salvadorans emigrated to the United States, and by 2008 they were one of the largest immigrant groups in the US.

El Salvador’s economy has historically been dominated by agriculture, beginning with the Spanish taking control of the indigenous cacao crop in the 16th century, with production centered in Izalco, and the use of balsam from the ranges of La Libertad and Ahuachapan. This was followed by a boom in the use of the indigo plant (añil in Spanish) in the 19th century, mainly for its use as a dye. Thereafter the focus shifted to coffee, which by the early 20th century accounted for 90% of export earnings. El Salvador has since reduced its dependence on coffee and embarked on diversifying its economy by opening up trade and financial links and expanding the manufacturing sector. The colón, the currency of El Salvador since 1892, was replaced by the United States dollar in 2001.

El Salvador ranks 124th among 189 countries in the Human Development Index. In addition to high rates of poverty and gang-related violent crime, El Salvador is the most egalitarian country in terms of income inequality in Latin America. Among 77 countries included in a 2021 study, El Salvador was one of the least complex economies for doing business.

HISTORY

Tomayate is a palaeontological site located on the banks of the river of the same name in the municipality of Apopa. The site has produced abundant Salvadoran megafauna fossils belonging to the Pleistocene. The palaeontological site was discovered accidentally in 2000, and in the following year, an excavation by the Museum of Natural History of El Salvador revealed several remnants of Cuvieronius and 18 other species of vertebrates including giant tortoises, Megatherium, Glyptodon, Toxodon, extinct horses, paleo-llamas. The site stands out from most Central American Pleistocene deposits, being more ancient and much richer, which provides valuable information of the Great American Interchange, in which the Central American isthmus land bridge was paramount. At the same time, it is considered the richest vertebrate site in Central America and one of the largest accumulations of proboscideans in the Americas.

Pre-Columbian. Sophisticated civilization in El Salvador dates to its settlement by the indigenous Lenca people; theirs was the first and the oldest indigenous civilization to settle in there. They were a union of Central American tribes that oversaw most of the isthmus from southern Guatemala to northern Panama, which they called Managuara. The Lenca of eastern El Salvador trace their origins to specific caves with ancient pictographs dating back to at least 600 AD and some sources say as far back as 7000 BC. There was also a presence of Olmecs, although their role is unclear. Their influence remains recorded in the form of stone monuments and artifacts preserved in western El Salvador, as well as the national museum. A Mayan population settled there in the Formative period, but their numbers were greatly diminished when the Ilopango supervolcano eruption caused a massive exodus.

Centuries later the area’s occupants were displaced by the Pipil people, Nahua-speaking groups who migrated from Anahuac beginning around 800 AD and occupied the central and western regions of El Salvador. The Nahua Pipil were the last indigenous people to arrive in El Salvador. They called their territory Kuskatan, a Nawat word meaning “The Place of Precious Jewels,” back-formed into Classical Nahuatl Cōzcatlān, and Hispanicized as Cuzcatlán. It was the largest domain in Salvadoran territory up until European contact. The term Cuzcatleco is commonly used to identify someone of Salvadoran heritage, although the majority of the eastern population has indigenous heritage of Lenca origin, as do their place names such as Intipuca, Chirilagua, and Lolotique.

Most of the archaeological sites in western El Salvador such as Lago de Guija and Joya De Ceren indicate a pre-Columbian Mayan culture. Cihuatan shows signs of material trade with northern Nahua culture, eastern Mayan and Lenca culture, and southern Nicaraguan and Costa Rican indigenous culture. Tazumal’s smaller B1-2 structure shows a talud-tablero style of architecture that is associated with Nahua culture and corresponds with their migration history from Anahuac. In eastern El Salvador, the Lenca site of Quelepa is highlighted as a major pre-Columbian cultural center and demonstrates links to the Mayan site of Copan in western Honduras as well as the previously mentioned sites in Chalchuapa, and Cara Sucia in western El Salvador. An investigation of the site of La Laguna in Usulutan has also produced Copador items that link it to the Lenca-Maya trade route.

European and African arrival (1522). By 1521, the indigenous population of the Mesoamerican area had been drastically reduced by the smallpox epidemic that was spreading throughout the territory, although it had not yet reached pandemic levels in Cuzcatlán or the northern portion Managuara. The first known visit by Spaniards to what is now Salvadoran territory was made by the admiral Andrés Niño, who led an expedition to Central America. He disembarked in the Gulf of Fonseca on 31 May 1522, at Meanguera island, naming it Petronila, and then traversed to Jiquilisco Bay on the mouth of Lempa River. The first indigenous people to have contact with the Spanish were the Lenca of eastern El Salvador.

Conquest of Cuzcatlán and Managuara

In 1524, after participating in the conquest of the Aztec Empire, Pedro de Alvarado, his brother Gonzalo, and their men crossed the Rio Paz southward into Cuzcatlec territory. The Spaniards were disappointed to discover that the Pipil had no gold or jewels like those they had found in Guatemala or Mexico, but they recognized the richness of the land’s volcanic soil.

Pedro Alvarado led the first incursion to extend their dominion to the domain of Cuzcatlan in June 1524. When he arrived at the borders of the kingdom, he saw that civilians had been evacuated. Cuzcatlec warriors moved to the coastal city of Acajutla and waited for Alvarado and his forces. Alvarado approached, confident that the result would be similar to what occurred in Mexico and Guatemala. He thought he would easily deal with this new indigenous force since the Mexican allies on his side and the Pipil spoke a similar language.

Alvarado described the Cuzcatlec soldiers as having shields decorated with colourful exotic feathers, a vest-like armour made of three-inch cotton which arrows could not penetrate, and long spears. Both armies suffered many casualties, with a wounded Alvarado retreating and losing a lot of his men, especially among the Mexican Indian auxiliaries. Once his army had regrouped, Alvarado decided to head to the Cuzcatlan capital and again faced armed Cuzcatlec. Wounded, unable to fight and hiding in the cliffs, Alvarado sent his Spanish men on their horses to approach the Cuzcatlec to see if they would fear the horses, but they did not retreat, Alvarado recalls in his letters to Hernán Cortés.

The Cuzcatlec attacked again, and on this occasion stole Spanish weaponry. Alvarado retreated and sent Mexican messengers to demand that the Cuzcatlec warriors return the stolen weapons and surrender to their opponent’s king. The Cuzcatlec responded with the famous response, “If you want your weapons, come get them”. As days passed, Alvarado, fearing an ambush, sent more Mexican messengers to negotiate, but these messengers never came back and were presumably executed.

The Spanish efforts were firmly resisted by Pipil and their Mayan-speaking neighbours. They defeated the Spaniards and what was left of their Tlaxcalan allies, forcing them to withdraw to Guatemala. After being wounded, Alvarado abandoned the war and appointed his brother, Gonzalo de Alvarado, to continue the task. Two subsequent expeditions (the first in 1525, followed by a smaller group in 1528) brought the Pipil under Spanish control, since the Pipil also were weakened by a regional epidemic of smallpox. In 1525, the conquest of Cuzcatlán was completed and the city of San Salvador was established. The Spanish faced much resistance from the Pipil and were not able to reach eastern El Salvador, the area of the Lencas.

In 1526 the Spanish founded the garrison town of San Miguel in northern Managuara—territory of the Lenca, headed by another explorer and conquistador, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, nephew of Pedro Alvarado. Oral history holds that a Maya-Lenca crown princess, Antu Silan Ulap I, organized resistance to the conquistadors. The kingdom of the Lenca was alarmed by de Moscoso’s invasion, and Antu Silan travelled from village to village, uniting all the Lenca towns in present-day El Salvador and Honduras against the Spaniards. Through surprise attacks and overwhelming numbers, they were able to drive the Spanish out of San Miguel and destroy the garrison.

For ten years the Lencas prevented the Spanish from building a permanent settlement. Then the Spanish returned with more soldiers, including about 2,000 forced conscripts from indigenous communities in Guatemala. They pursued the Lenca leaders further up into the mountains of Intibucá.

Antu Silan Ulap eventually handed over control of the Lenca resistance to Lempira (also called Empira). Lempira was noteworthy among indigenous leaders in that he mocked the Spanish by wearing their clothes after capturing them and using their weapons captured in battle. Lempira fought in command of thousands of Lenca forces for six more years in Managuara until he was killed in battle. The remaining Lenca forces retreated into the hills. The Spanish were then able to rebuild their garrison town of San Miguel in 1537.

Colonial period (1525–1821). During the colonial period, San Salvador and San Miguel were part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, also known as the Kingdom of Guatemala (Spanish: Reino de Guatemala), created in 1609 as an administrative division of New Spain. The Salvadoran territory was administered by the mayor of Sonsonate, with San Salvador being established as an intendencia in 1786.

In 1811, a combination of internal and external factors motivated Central American elites to attempt to gain independence from the Spanish Crown. The most important internal factors were the desire of local elites to control the country’s affairs free of involvement from Spanish authorities, and the long-standing Creole aspiration for independence. The main external factors motivating the independence movement were the success of the French and American revolutions in the 18th century, and the weakening of the Spanish Crown’s military power as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, with the resulting inability to control its colonies effectively.

In November 1811 Salvadoran priest José Matías Delgado rang the bells of Iglesia La Merced in San Salvador, calling for insurrection and launching the 1811 Independence Movement. This insurrection was suppressed, and many of its leaders were arrested and served sentences in jail. Another insurrection was launched in 1814, which was also suppressed.

Independence (1821). In 1821 in light of unrest in Guatemala, Spanish authorities capitulated and signed the Act of Independence of Central America, which released all of the Captaincy of Guatemala (comprising current territories of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica and the Mexican state of Chiapas) from Spanish rule and declared its independence. In 1821, El Salvador joined Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua in a union named the Federal Republic of Central America.

In early 1822, the authorities of the newly independent Central American provinces, meeting in Guatemala City, voted to join the newly constituted First Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide. El Salvador resisted, insisting on autonomy for the Central American countries. A Mexican military detachment marched to San Salvador and suppressed dissent, but with the fall of Iturbide on 19 March 1823, the army decamped back to Mexico. Shortly thereafter, the authorities of the provinces revoked the vote to join Mexico, deciding instead to form a federal union of the five remaining provinces. (Chiapas permanently joined Mexico at this juncture.) When the Federal Republic of Central America dissolved in 1841, El Salvador maintained its own government until it joined Honduras and Nicaragua in 1896 to form the Greater Republic of Central America, which dissolved in 1898.

After the mid-19th century, the economy was based on coffee growing. As the world market for indigo withered away, the economy prospered or suffered as the world coffee price fluctuated. The enormous profits that coffee yielded as a monoculture export served as an impetus for the concentration of land into the hands of an oligarchy of just a few families. Throughout the last half of the 19th century, a succession of presidents from the ranks of the Salvadoran oligarchy, nominally both conservative and liberal, generally agreed on the promotion of coffee as the predominant cash crop, the development of infrastructure (railroads and port facilities) primarily in support of the coffee trade, the elimination of communal landholdings to facilitate further coffee production, the passage of anti-vagrancy laws to ensure that displaced campesinos and other rural residents provided sufficient labour for the coffee fincas (plantations), and the suppression of rural discontent. In 1912, the national guard was created as a rural police force.

20th century. In 1898, General Tomas Regalado gained power by force, deposing Rafael Antonio Gutiérrez and ruling as president until 1903. Once in office he revived the practice of presidents designating their successors. After serving his term, he remained active in the Army of El Salvador and was killed 11 July 1906, at El Jicaro during a war against Guatemala. Until 1913 El Salvador was politically stable, with undercurrents of popular discontent. When President Manuel Enrique Araujo was killed in 1913, many hypotheses were advanced for the political motive of his murder.

Araujo’s administration was followed by the Melendez-Quinonez dynasty that lasted from 1913 to 1927. Pio Romero Bosque, ex-Minister of the Government and a trusted collaborator of the dynasty, succeeded President Jorge Meléndez and in 1930 announced free elections, in which Arturo Araujo came to power on 1 March 1931 in what was considered the country’s first freely contested election. His government lasted only nine months before it was overthrown by junior military officers who accused his Labor Party of lacking political and governmental experience and of using its government offices inefficiently. President Araujo faced general popular discontent, as the people had expected economic reforms and the redistribution of land. There were demonstrations in front of the National Palace from the first week of his administration. His vice president and minister of war was General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez.

In December 1931, a coup d’état was organized by junior officers and led by Martínez. Only the First Regiment of Cavalry and the National Police defended the presidency (the National Police had been on its payroll), but later that night, after hours of fighting, the badly outnumbered defenders surrendered to rebel forces. The Directorate, composed of officers, hid behind a shadowy figure, a rich anti-Communist banker called Rodolfo Duke, and later installed the ardent fascist Martínez as president. The revolt was probably caused by the army’s discontent at not having been paid by President Araujo for some months. Araujo left the National Palace and unsuccessfully tried to organize forces to defeat the revolt.

The U.S. Minister in El Salvador met with the Directorate and later recognized the government of Martínez, which agreed to hold presidential elections. He resigned six months prior to running for re-election, winning back the presidency as the only candidate on the ballot. He ruled from 1935 to 1939, then from 1939 to 1943. He began a fourth term in 1944 but resigned in May after a general strike. Martínez had said he was going to respect the constitution, which stipulated he could not be re-elected, but he refused to keep his promise.

La Matanza. From December 1931, the year of the coup that brought Martínez to power, there was brutal suppression of rural resistance. The most notable event was the February 1932 Salvadoran peasant uprising, originally led by Farabundo Martí and Abel Cuenca, and university students Alfonso Luna and Mario Zapata, but these leaders were captured before the planned insurrection. Only Cuenca survived; the other insurgents were killed by the government. After the capture of the movement leaders, the insurrection erupted in a disorganized and mob-controlled fashion, resulting in government repression that was later referred to as La Matanza (The Massacre), because tens of thousands of citizens died in the ensuing chaos on the orders of President Martinez.

In the unstable political climate of the previous few years, the social activist and revolutionary leader Farabundo Martí helped found the Communist Party of Central America, and led a Communist alternative to the Red Cross called International Red Aid, serving as one of its representatives. Their goal was to help poor and underprivileged Salvadorans through the use of Marxist–Leninist ideology (strongly rejecting Stalinism). In December 1930, at the height of the country’s economic and social depression, Martí was once again exiled because of his popularity among the nation’s poor and rumours of his upcoming nomination for president the following year. Once Arturo Araujo was elected president in 1931, Martí returned to El Salvador, and along with Alfonso Luna and Mario Zapata began the movement that was later truncated by the military.

They helped start a guerrilla revolt of indigenous farmers. The government responded by killing over 30,000 people at what was to have been a “peaceful meeting” in 1932. The peasant uprising against Martínez was crushed by the Salvadoran military ten days after it had begun. The Communist-led rebellion, fomented by collapsing coffee prices, enjoyed some initial success, but was soon drowned in a bloodbath. President Martínez, who had toppled an elected government only weeks earlier, ordered the defeated Martí shot after a perfunctory hearing.

Historically, the high Salvadoran population density has contributed to tensions with neighbouring Honduras, as land-poor Salvadorans emigrated to less densely populated Honduras and established themselves as squatters on unused or underused land. This phenomenon was a major cause of the 1969 Football War between the two countries. As many as 130,000 Salvadorans were forcibly expelled or fled from Honduras.

The Christian Democratic Party (PDC) and the National Conciliation Party (PCN) were active in Salvadoran politics from 1960 until 2011, when they were disbanded by the Supreme Court because they had failed to win enough votes in the 2004 presidential election; Both parties have since reconstituted. They share common ideals, but one represents the middle class and the latter the interests of the Salvadoran military.

PDC leader José Napoleón Duarte was the mayor of San Salvador from 1964 to 1970, winning three elections during the regime of PCN President Julio Adalberto Rivera Carballo, who allowed free elections for mayors and the National Assembly. Duarte later ran for president with a political grouping called the National Opposition Union (UNO) but was defeated in the 1972 presidential elections. He lost to the ex-Minister of Interior, Col. Arturo Armando Molina, in an election that was widely viewed as fraudulent; Molina was declared the winner even though Duarte was said to have received a majority of the votes. Duarte, at some army officers’ request, supported a revolt to protest the election fraud, but was captured, tortured and later exiled. Duarte returned to the country in 1979 to enter politics after working on projects in Venezuela as an engineer.

Salvadoran Civil War (1979–1992). On 15 October 1979, a coup d’état brought the Revolutionary Government Junta of El Salvador to power. It nationalized many private companies and took over much privately owned land. The purpose of this new junta was to stop the revolutionary movement already underway in response to Duarte’s stolen election. Nevertheless, the oligarchy opposed agrarian reform, and a junta formed with young reformist elements from the army such as Colonels Adolfo Arnoldo Majano and Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez, as well as with progressives such as Guillermo Ungo and Alvarez.

Pressure from the oligarchy soon dissolved the junta because of its inability to control the army in its repression of the people fighting for unionization rights, agrarian reform, better wages, accessible health care and freedom of expression. In the meantime, the guerrilla movement was spreading to all sectors of Salvadoran society. Middle and high school students were organized in MERS (Movimiento Estudiantil Revolucionario de Secundaria, Revolutionary Movement of Secondary Students); college students were involved with AGEUS (Asociacion de Estudiantes Universitarios Salvadorenos; Association of Salvadoran College Students); and workers were organized in BPR (Bloque Popular Revolucionario, Popular Revolutionary Block). In October 1980, several other major guerrilla groups of the Salvadoran left had formed the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or FMLN. By the end of the 1970s, government-contracted death squads were killing about 10 people each day. Meanwhile, the FMLN had 6,000 – 8,000 active guerrillas and hundreds of thousands of part-time militia, supporters, and sympathizers.

The U.S. supported and financed the creation of a second junta to change the political environment and stop the spread of a leftist insurrection. Napoleón Duarte was recalled from his exile in Venezuela to head this new junta. However, a revolution was already underway and his new role as head of the junta was seen by the general population as opportunistic. He was unable to influence the outcome of the insurrection.

Óscar Romero, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador, denounced injustices and massacres committed against civilians by government forces. He was considered “the voice of the voiceless”, but he was assassinated by a death squad while saying Mass on 24 March 1980. Some consider this to be the beginning of the full Salvadoran Civil War, which lasted from 1980 to 1992.

An unknown number of people “disappeared” during the conflict, and the UN reports that more than 75,000 were killed. The Salvadoran Army’s US-trained Atlacatl Battalion was responsible for the El Mozote massacre where more than 800 civilians were murdered, over half of them children, the El Calabozo massacre, and the murder of UCA scholars.

On 16 January 1992, the government of El Salvador, represented by president Alfredo Cristiani, and the FMLN, represented by the commanders of the five guerrilla groups – Shafik Handal, Joaquín Villalobos, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, Francisco Jovel and Eduardo Sancho, all signed peace agreements brokered by the United Nations ending the 12-year civil war. This event, held at Chapultepec Castle in Mexico, was attended by U.N. dignitaries and other representatives of the international community. After signing the armistice, the president stood up and shook hands with all the now ex-guerrilla commanders, an action which was widely admired.

Post-war (1992–present). The so-called Chapultepec Peace Accords mandated reductions in the size of the army, and the dissolution of the National Police, the Treasury Police, the National Guard and the Civilian Defence, a paramilitary group. A new Civil Police was to be organized. Judicial immunity for crimes committed by the armed forces ended; the government agreed to submit to the recommendations of a Commission on the Truth for El Salvador (Comisión de la Verdad Para El Salvador), which would “investigate serious acts of violence occurring since 1980, and the natur,e and effects of the violence, and…recommend methods of promoting national reconciliation”. In 1993 the Commission delivered its findings reporting human rights violations on both sides of the conflict. Five days later the Salvadoran legislature passed an amnesty law for all acts of violence during the period.

From 1989 until 2004, Salvadorans favoured the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party, voting in ARENA presidents in every election (Alfredo Cristiani, Armando Calderón Sol, Francisco Flores Pérez, Antonio Saca) until 2009. The unsuccessful attempts of the left-wing party to win presidential elections led to its selection of a journalist rather than a former guerrilla leader as a candidate. On 15 March 2009, Mauricio Funes, a television figure, became the first president from the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) party. He was inaugurated on 1 June 2009. One focus of the Funes government has been revealing the alleged corruption from the past government.

ARENA formally expelled Saca from the party in December 2009. With 12 loyalists in the National Assembly, Saca established his own party, GANA (Gran Alianza por la Unidad Nacional or Grand Alliance for National Unity), and entered into a tactical legislative alliance with the FMLN. After three years in office, with Saca’s GANA party providing the FMLN with a legislative majority, Funes had not taken action to either investigate or to bring corrupt former officials to justice.

Economic reforms since the early 1990s brought major benefits in terms of improved social conditions, diversification of the export sector, and access to international financial markets at investment grade level. Crime remains a major problem for the investment climate. Early in the new millennium, El Salvador’s government created the Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales — the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) — in response to climate change concerns.

In March 2014, Salvador Sanchez Ceren of the FMLN narrowly won the election. He was sworn in as president on 31 May 2014. He was the first former guerrilla to become the President of El Salvador.

In October 2017, an El Salvador court ruled that former leftist President Mauricio Funes, in office since 2009 until 2014, and one of his sons, had illegally enriched themselves. Funes had sought asylum in Nicaragua in 2016.

In September 2018, former conservative President Antonio “Tony” Saca, in office since 2004 until 2009, was sentenced to 10 years in prison after he pleaded guilty to diverting more than US$300 million in state funds to his own businesses and third parties.

Presidency of Nayib Bukele since 2019. On 1 June 2019, Nayib Bukele became the new President of El Salvador. Bukele was the winner of February 2019 presidential election. He represented the center-right Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA). Two main parties, left-wing FMLN and the right-wing ARENA, had dominated politics in El Salvador over the past three decades.

According to a report by the International Crisis Group (ICG) 2020, the homicide rates, murders in El Salvador had dropped by as much as 60 percent since Bukele became president in June 2019. The reason might have been a “non-aggression deal” between parts of the government and the gangs.

The party Nuevas Ideas, founded by Bukele, with its allies (GANA–Nuevas Ideas) won around two-thirds of the vote in the February 2021 legislative elections. His party won supermajority of 56 seats in the 84-seat parliament. The supermajority enables Bukele to appoint judges and to pass laws, for instance, to remove presidential term limits. On 8 June 2021, at the initiative of president Bukele, pro-government deputies in the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador voted legislation to make Bitcoin legal tender in the country. In September 2021, El Salvador’s Supreme Court decided to allow Bukele to run for a second term in 2024, despite the fact that the constitution prohibits the president to serve two consecutive terms in office. The decision was organized by judges appointed to the court by President Bukele.

In January 2022, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) urged El Salvador to reverse its decision to make cryptocurrency Bitcoin legal tender. Bitcoin had rapidly lost about half of its value, meaning economic difficulties for El Salvador. President Bukele has announced his plans to build a Bitcoin city at the base of a volcano in El Salvador.

GEOGRAPHY

El Salvador lies in the isthmus of Central America between latitudes 13° and 15°N, and longitudes 87° and 91°W. It stretches 270 km (168 mi) from west-northwest to east-southeast and 142 km (88 mi) north to south, with a total area of 21,041 km2 (8,124 sq mi). As the smallest country in continental America, El Salvador is affectionately called Pulgarcito de America (the “Tom Thumb of the Americas”). El Salvador shares borders with Guatemala and Honduras, the total national boundary length is 546 km (339 mi): 126 miles (203 km) with Guatemala and 343 km (213 mi) with Honduras. It is the only Central American country that has no Caribbean coastline. The coastline on the Pacific is 307 km (191 mi) long.

El Salvador has over 300 rivers, the most important of which is the Rio Lempa. Originating in Guatemala, the Rio Lempa cuts across the northern range of mountains, flows along much of the central plateau, and cuts through the southern volcanic range to empty into the Pacific. It is El Salvador’s only navigable river. It and its tributaries drain about half of the country’s area. Other rivers are generally short and drain the Pacific lowlands or flow from the central plateau through gaps in the southern mountain range to the Pacific. These include the Goascorán, Jiboa, Torola, Paz and the Río Grande de San Miguel.

There are several lakes enclosed by volcanic craters in El Salvador, the most important of which are Lake Ilopango (70 km2 or 27 sq mi) and Lake Coatepeque (26 km2 or 10 sq mi). Lake Güija is El Salvador’s largest natural lake (44 km2 or 17 sq mi). Several artificial lakes were created by the damming of the Lempa, the largest of which is Cerrón Grande Reservoir (135 km2 or 52 sq mi). There are a total 320 km2 (123.6 sq mi) of water within El Salvador’s borders.

The highest point in El Salvador is Cerro El Pital, at 2,730 metres (8,957 ft), on the border with Honduras. Two parallel mountain ranges cross El Salvador to the west with a central plateau between them and a narrow coastal plain hugging the Pacific. These physical features divide the country into two physiographic regions. The mountain ranges and central plateau, covering 85% of the land, comprise the interior highlands. The remaining coastal plains are referred to as the Pacific lowlands.

Climate: El Salvador has a tropical climate with pronounced wet and dry seasons. Temperatures vary primarily with elevation and show little seasonal change. The Pacific lowlands are uniformly hot; the central plateau and mountain areas are more moderate. The rainy season extends from May to October; this time of year is referred to as invierno or winter. Almost all the annual rainfall occurs during this period; yearly totals, particularly on southern-facing mountain slopes, can be as high as 2170 mm. Protected areas and the central plateau receive less, although still significant, amounts. Rainfall during this season generally comes from low pressure systems formed over the Pacific and usually falls in heavy afternoon thunderstorms.

From November through April, the northeast trade winds control weather patterns; this time of year is referred to as verano, or summer. During these months, air flowing from the Caribbean has lost most of its precipitation while passing over the mountains in Honduras. By the time this air reaches El Salvador, it is dry, hot, and hazy, and the country experiences hot weather, excluding the northern higher mountain ranges, where temperatures are generally cooler.

Natural disasters.

Extreme weather events. El Salvador’s position on the Pacific Ocean also makes it subject to severe weather conditions, including heavy rainstorms and severe droughts, both of which may be made more extreme by the El Niño and La Niña effects. Hurricanes occasionally form in the Pacific with the notable exception of Hurricane Mitch, which formed in the Atlantic and crossed Central America.

In the summer of 2001 a severe drought destroyed 80% of El Salvador’s crops, causing famine in the countryside. On 4 October 2005, severe rains resulted in dangerous flooding and landslides, which caused at least 50 deaths.

Earthquakes and volcanic activity: El Salvador lies along the Pacific Ring of Fire and is thus subject to significant tectonic activity, including frequent earthquakes and volcanic activity. The capital San Salvador was destroyed in 1756 and 1854, and it suffered heavy damage in the 1919, 1982, and 1986 tremors. Recent examples include the earthquake on 13 January 2001 that measured 7.7 on the Richter magnitude scale and caused a landslide that killed more than 800 people; and another earthquake only a month later, on 13 February 2001, that killed 255 people and damaged about 20% of the country’s housing. A 5.7 Mw earthquake in 1986 resulted in 1,500 deaths, 10,000 injuries, and 100,000 people left homeless.

El Salvador has over twenty volcanoes; two of them, San Miguel and Izalco, have been active in recent years. From the early 19th century to the mid-1950s, Izalco erupted with a regularity that earned it the name “Lighthouse of the Pacific”. Its brilliant flares were clearly visible for great distances at sea, and at night its glowing lava turned it into a brilliant luminous cone. The most recent destructive volcanic eruption took place on 1 October 2005, when the Santa Ana Volcano spewed a cloud of ash, hot mud and rocks that fell on nearby villages and caused two deaths. The most severe volcanic eruption in this area occurred in the 5th century AD when the Ilopango volcano erupted with a VEI strength of 6, producing widespread pyroclastic flows and devastating Mayan cities.

Flora and fauna. It is estimated that there are 500 species of birds, 1,000 species of butterflies, 400 species of orchids, 800 species of trees, and 800 species of marine fish in El Salvador.

There are eight species of sea turtles in the world; six of them nest on the coasts of Central America, and four make their home on the Salvadoran coast: the leatherback turtle, the hawksbill, the green sea turtle, and the olive ridley. The hawksbill is critically endangered.

Recent conservation efforts provide hope for the future of the country’s biological diversity. In 1997, the government established the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources. A general environmental framework law was approved by the National Assembly in 1999. Several non-governmental organizations are doing work to safeguard some of the country’s most important forested areas. Foremost among these is SalvaNatura, which manages El Impossible, the country’s largest national park under an agreement with El Salvador’s environmental authorities.

El Salvador is home to six terrestrial ecosystems: Central American montane forests, Sierra Madre de Chiapas moist forests, Central American dry forests, Central American pine-oak forests, Gulf of Fonseca mangroves, and Northern Dry Pacific Coast mangroves.[84] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.05/10, ranking it 136th globally out of 172 countries.

Politics. El Salvador has a multi-party system. Two political parties, the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) have tended to dominate elections. ARENA candidates won four consecutive presidential elections until the election of Mauricio Funes of the FMLN in March 2009. The FMLN Party is leftist in ideology, and is split between the dominant Marxist-Leninist faction in the legislature, and the social liberal wing led by Mauricio Funes until 2014. However, the two-party dominance was broken after Nayib Bukele, a candidate from GANA won the 2019 Salvadoran presidential election. In February 2021, the results of legislative election caused a major change in the politics of El Salvador. The new allied party of president Nayib Bukele, Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas) won the biggest congressional majority in the country’s history.

HUMAN RIGHTS

Amnesty International has drawn attention to several arrests of police officers for unlawful police killings. Other issues to gain Amnesty International’s attention include missing children, failure of law enforcement to properly investigate and prosecute crimes against women, and rendering organized labour illegal. Discrimination against LGBT people in El Salvador is very widespread. According to 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 62% of Salvadorans believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.

ECONOMY

El Salvador’s economy has been hampered at times by natural disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes, by government policies that mandate large economic subsidies, and by official corruption. Subsidies became such a problem that in April 2012, the International Monetary Fund suspended a $750 million loan to the central government. President Funes’ chief of cabinet, Alex Segovia, acknowledged that the economy was at the “point of collapse”.

Gross domestic product (GDP) in purchasing power parity estimate for 2021 is US$57.95 billion growing real GDP at 4.2% for 2021. The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 64.1%, followed by the industrial sector at 24.7% (2008 est.) and agriculture represents 11.2% of GDP (2010 est.). The GDP grew after 1996 at an annual rate that averaged 3.2% real growth. The government committed to free market initiatives and the 2007 GDP’s real growth rate hit 4.7%.

In December 1999, net international reserves equaled US$1.8 billion. Having this hard currency buffer to work with, the Salvadoran government undertook a monetary integration plan beginning in January 2001 by which the U.S. dollar became legal tender alongside the Salvadoran colón, and all formal accounting was done in U.S. dollars. With the adoption of the U.S. dollar, El Salvador lost control over monetary policy. Any counter-cyclical policy response to the downturn must be through fiscal policy, which is constrained by legislative requirements for a two-thirds majority to approve any international financing. As of December 2017, net international reserves stood at $3.57 billion.

It has long been a challenge in El Salvador to develop new growth sectors for a more diversified economy. In the past, the country produced gold and silver, but recent attempts to reopen the mining sector, which were expected to add hundreds of millions of dollars to the local economy, collapsed after President Saca shut down the operations of Pacific Rim Mining Corporation. Nevertheless, according to the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies (Instituto Centroamericano for Estudios Fiscales), the contribution of metallic mining was a minuscule 0.3% of the country’s GDP between 2010 and 2015. Saca’s decision although not lacking political motives, had strong support from local residents and grassroots movements in the country. President Funes later rejected a company’s application for a further permit based on the risk of cyanide contamination on one of the country’s main rivers.

As with other former colonies, El Salvador was considered a mono-export economy (an economy that depended heavily on one type of export) for many years. During colonial times, El Salvador was a thriving exporter of indigo, but after the invention of synthetic dyes in the 19th century, the newly created modern state turned to coffee as the main export.