BRITAIN’S STONE AGE BUILDING BOOM

IT’S NOT JUST STONEHENGE: NEW DISCOVERIES REVEAL AN ERA WHEN AWE-INSPIRING MONUMENTS WERE ALL THE RAGE.

Something momentous was in the air in the south of Britain about 4,500 years ago during the dying days of the Neolithic era, the final chapter of the Stone Age. Whatever it was—religious zeal, bravura, a sense of impending change—it cast a spell over the inhabitants and stirred them into a frenzy of monument building.

In an astonishingly brief span of time—perhaps as little as a century—people who lacked metal tools, horsepower, and the wheel erected many of Britain’s huge stone circles, colossal wooden palisades, and grand avenues of standing stones. In the process, they robbed forests of their biggest trees and moved millions of tons of earth.

“It was like a mania sweeping the countryside, an obsession that drove them to build bigger and bigger, more and more, better and more complex,” says Susan Greaney, an archaeologist with the nonprofit English Heritage.

The most famous relic of that long-ago building boom is Stonehenge, the huddle of standing stones that draws millions of visitors to England’s Salisbury Plain. For centuries, the ancient megalith has intrigued and mystified all who’ve seen it, including the medieval historian Henry of Huntingdon. Writing around 1130—the first known reference to Stonehenge in print—he declared it to be one of the wonders of England, adding that no one knew how it was built or why.

‘PEOPLE LIKE TO SEE SITES THAT HAVE ENDURED OVER TIME

AND COME THROUGH MANY RISES AND FALLS IN THE STORY OF HUMANITY.’

Stonehenge attracts up to 1.6 million visitors a year, yet many connect with the structure in personal ways. For Londoner Gary Forrester and his baby daughter, Vivienne, it was forging a connection with the Earth by removing their shoes and walking barefoot on a warm, late summer evening.

One of the world’s iconic monuments, Stonehenge has been studied for centuries. Yet new technologies, says archaeologist Vince Gaffney, are “transforming our understanding of ancient landscapes—even Stonehenge, a place we thought we knew well.”

One of the world’s iconic monuments, Stonehenge has been studied for centuries. Yet new technologies, says archaeologist Vince Gaffney, are “transforming our understanding of ancient landscapes—even Stonehenge, a place we thought we knew well.”

Photographer Reuben Wu uses a powerful light attached to a drone to illuminate the landscape, capturing multiple exposures of a scene and layering them together to create the final image.

In the 900 years since, the solar-aligned stone ring has been attributed to Romans, Druids, Vikings, Saxons, and even King Arthur’s court magician, Merlin. Yet the truth is the most inscrutable of all, for it was built by a vanished people who left no written language, no tales or legends, only a scatter of bones, potsherds, stone and antler tools—and an array of equally mysterious monuments, some of which appear to have eclipsed Stonehenge in scale and grandeur.

One of the most stunning structures, known today as the Mount Pleasant mega-henge, was built on a grassy upland overlooking the Rivers Frome and Winterborne. An army of workers used antler picks and cow-bone shovels to dig an enormous ring-shaped ditch and embankment, or henge, three-quarters of a mile in circumference—more than three times larger than Stonehenge’s ditch and bank. Inside the great earthwork, the builders reared a circle of towering timber posts from oak trees, some six feet thick and weighing more than 17 tons.

Opponents of a controversial plan to build a highway tunnel under the Stonehenge World Heritage site protest in London outside Britain’s Royal Courts of Justice in June 2021. “We need to hold authority accountable,” said senior Druid and pagan priest King Arthur Pendragon. The court halted the plan, but the project is still under review.

“We’re all familiar with Stonehenge,” Greaney says. “After all, it’s built of stone, and it survived. But what were these huge timber structures like? These things were massive and would have dominated the landscape for centuries.”

Antiquarians and archaeologists have been picking over England’s ancient henges, mounds, and stone circles since the 17th century. Yet it wasn’t until recent years that anyone realized many of these mega-monuments had been built at roughly the same time, and in a mad rush. “It was always assumed these huge monuments had evolved separately and over many centuries,” Greaney says.

STONE AGE SITE, MODERN WORLD

Now a burst of cutting-edge technologies has thrown open new windows into the past, allowing archaeologists to piece together the world of the great Stone Age monuments of southern Britain and the people who built them with a vividness that would have been inconceivable a few decades ago.

“It’s almost like starting over from scratch,” says Jim Leary, a lecturer in field archaeology at the University of York. “A lot of the things we were taught as undergraduates in the 1990s we know now simply aren’t true.”

STONEHENGE

BEHIND THE COVER

How the spirit of ancient Stonehenge was captured with a 21st-century drone

“Nobody believed it could have happened that way,” Leary says. “The idea of the agricultural revolution arriving in Britain because of a wholesale migration of people seemed too simplistic. Everyone was looking for a more nuanced narrative—a diffusion of ideas, not just masses of people getting on boats. But it turns out it was that simple.”

LEFT: A protester who goes by the name of “Thistle” catches a moment of peace at Stonehenge Heritage Action Camp (HAC) in woods next to the A303 highway by Stonehenge. RIGHT: Activists against the proposed highway tunnel under part of the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage site established the Stonehenge HAC. Protests are ongoing; the project is still under consideration.

Some of the migrants made the short hop at the narrowest part of the English Channel, crossing what is now the Strait of Dover. Others, from Brittany in western France, made longer, more dangerous open water crossings to western Britain and Ireland. Some of these earliest Breton pioneers settled along the rugged coast of Pembrokeshire in Wales. It may have been their descendants, some 40 generations later, who built the first edition of Stonehenge.

ARCHAEOLOGISTS know to look to Wales for the start of the story primarily because of a sharp-eyed geologist named Herbert Thomas. Think of Stonehenge and you’ll almost certainly envision its huge sarsen trilithons. But another, much smaller, type of monolith huddles within the horseshoe of trilithons—the bluestones. Unlike the sarsens, which are made of local silica-rich stone, the bluestones are entirely alien to the landscape. There are no rock types like them anywhere near Stonehenge.

The bluestone monoliths weigh an average of two tons each. Where they came from, and how they came to be arranged in a ring in the middle of Salisbury Plain, was already a centuries-old mystery when Thomas was shown a sampling of them in 1923. Among the pieces was a type of bluestone called spotted dolerite, and he recalled seeing outcrops of that same rock many years earlier while hiking in the Preseli Hills, a wild moorland in Pembrokeshire some 175 miles from Stonehenge. After further examination, Thomas narrowed down the source of the bluestone to rocky outcrops called Carn Meini.

Stonehenge, the most complex and famous stone circle in the British Isles, is just one of about 1,300 of these prehistoric monuments. Several late Neolithic mega-sites, including many giant earthwork and timber circles, provide clues that their builders travelled long distances to take part in these communal projects.

A popular monument type for thousands of years, stone circles range from just a few stones to complex arrangements of over a hundred.

The Stonehenge and Avebury units form the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage site. There are two main stone types at Stonehenge: two-to-four-ton bluestones from 175 miles away in Wales and 20-to-40-ton sarsens (sandstone) sourced nearby.

Stone circles are thought to be civic gathering sites, worship centers, or burial sites. Henge enclosures often surround timber or stone structures. A henge is a banked, circular ditch. Monumental mounds of earth can be found not far from prominent enclosures.

Palisaded enclosures are fences made of timbers driven into the ground.

FIVE GIANTS Avebury, Silbury Hill, Durrington Walls, Stonehenge, Mount Pleasant

These colossal monument sites of southern Britain transformed over time with dynamic bursts of collective and creative activity. Construction was especially active during a Neolithic building boom that peaked around 2500 B.C.

STONEHENGE

The circle is precisely arranged to frame the sun during the solstices. With at least 64 cremations, it has more burials than any other late Neolithic cemetery in Britain.

Carpentry techniques to interlock the stones led to unprecedented strength and durability.

Tongue and groove

Heel Stone 40 tons

Diameter 360 ft

Sarsen’s Average weight: is 20 tons. One smaller sarsen doesn’t match the others. Some experts speculate that the circle was damaged or incomplete.

Bluestone Average weight: two tons. Bluestones were regularly rearranged; their exact position in 2500 B.C. is unknown.

Full stone: 29 ft 31 tons

Woodhenge – Timber monuments were often found in larger enclosures and may have been shrines or temples. At the end of the settlement’s use, its perimeter was encircled by a palisade of wooden posts (A), then later by a large henge (B), possibly to memorialize the site’s history.

Durrington Walls – Britain’s biggest henge—two miles from Stonehenge and thought to be home to its builders for about 10 years—is the largest known Neolithic settlement.

Some 4,000 people came from near and far to work, trade, and feast during farming off-seasons.

Ditch 30 ft deep. Gleaming white when freshly dug, ditches and banks cut into the chalk-rich ground made for a striking visual. An earthen mound may have provided a vantage point into the henge. Posts were later burned, possibly as part of an attack—or a ritual.

MOUNT PLEASANT The monument was dominated by a timber fence just inside its henge. Closely spaced posts suggest that access—physical and visual—was carefully controlled. Timbers made up the palisade. Postholes are all that’s now left of rotted timbers, perhaps carved, charred, or used to support lintels.

SILBURY HILL Built over several generations, Europe’s largest artificial mound holds no known human remains. Its purpose may have been the communal act of building. 7.5 million hours of labour to build. What began as a modest pile of gravel grew upward and outward—fed by an encircling ditch.

Earliest mound 100 ft tall Bank, Ditch quarry, Retaining walls of chalk and sarsen boulders held soil in place. Diameter 525 ft

In recent years Richard Bevins, a geologist with the National Museum of Wales, and fellow geologist Rob Ixer, from University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, have been revisiting Thomas’s work using 21st-century technologies with flashy names such as x-ray fluorescence spectrometry and ICP-MS laser ablation. The pair have identified four outcrops in the Preseli Hills that contributed bluestone monoliths to Stonehenge. (Turns out, Thomas was off the mark by only a mile or two.) For archaeologists hunting clues to the Stonehenge story, it’s a fresh start—one made all the more tantalizing by a breakthrough in biochemistry.

A Belgian researcher named Christophe Snoeck pioneered a technique to retrieve isotopes from cremated remains that reveal where an individual lived during the last decade of life. He analyzed the bones of 25 people whose cremated remains had been buried at Stonehenge in the early days, when the bluestones were erected, and found that nearly half of them had lived miles from Stonehenge. When paired with archaeological evidence, north Devon and southwestern Wales are likely possibilities.

PRESELI HILLS Stonehenge’s saga begins in the craggy hills of Wales, where geologists have pinpointed Carn Goedog and nearby outcrops as the source of most of the monument’s bluestones. Why the builders hauled two-ton stones 175 miles to Salisbury Plain has inspired many theories but few rock-solid answers

Incredibly, he was even able to pick up carbon and oxygen isotope signatures from the smoke of the funeral pyres that had consumed the bodies. These opened yet another window into the past, indicating that in some of the cremations, the trees that had supplied the wood for the fire may have grown in dense, canopied forests, not the lightly wooded landscape around Stonehenge.

“We can’t say for certain that the people buried at Stonehenge came from southwestern Wales,” says Oxford University archaeology professor Rick Schulting. “But archaeology is like building a court case—you look at the preponderance of evidence. The fact that we know the bluestones came from the Preseli Hills in Wales means that’s a good place to start looking.”

IT’S A CHILLY dawn in mid-September, and a dense mist has closed in around Waun Mawn, the site of four remaining ancient stones in the Preseli Hills. The dramatic coastline here is many miles and a world away from the windswept plain where Stonehenge stands today. The mist has turned archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Mike Parker Pearson and his team into ghostly silhouettes with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows.

Parker Pearson, an expert in British prehistory at University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, has come to this desolate spot to investigate the possibility, first suggested in a 12th-century legend, that the standing stones at Stonehenge may have come from an earlier stone circle in a faraway land. The medieval chronicler and cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote a rollicking tale of how Stonehenge’s monoliths were taken from a stone circle in Ireland after a great battle and transported by magic and by boat to where they stand today.

WAUN MAWN

Testing a theory that Stonehenge was first built in Wales and later moved, volunteers dig for clues at Waun Mawn, a dismantled stone circle in the Preseli Hills that was strikingly similar to Stonehenge but centuries older. Archaeologists uncovered pits where upright stones once stood, but few of the original stones remain. Where did they go? It’s still unclear whether any ended up at Stonehenge.

Archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson rests on a remnant of a 5,300-year-old stone circle in Wales known as Waun Mawn, which predates Stonehenge.

Archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson rests on a remnant of a 5,300-year-old stone circle in Wales known as Waun Mawn, which predates Stonehenge.

At Waun Mawn, just one stone still stands; three more lie in the grass. The others were taken away long ago. Where is yet unknown.

At Waun Mawn, just one stone still stands; three more lie in the grass. The others were taken away long ago. Where is yet unknown.

‘OF THE HUNDREDS OF STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, STONEHENGE IS THE ONLY ONE WHOSE STONES WERE BROUGHT FROM A GREAT DISTANCE.’

Through excavation work such as this trench, Parker Pearson confirmed that Waun Mawn had been a stone circle. Now he hopes to find clues to where the stones went.

Through excavation work such as this trench, Parker Pearson confirmed that Waun Mawn had been a stone circle. Now he hopes to find clues to where the stones went.

“While the story is fanciful, there’s a chance it may have been based on an old oral tradition that had a kernel of truth to it,” says Parker Pearson. “For one thing, the stones at Stonehenge actually were transported. Of the hundreds of stone circles in Britain, Stonehenge is the only one whose stones were brought from a great distance. Every other one is made of local stone. It’s something that could not have been known in Geoffrey’s day.”

What’s more, he points out, this region of Wales was considered Irish territory at the time Geoffrey was writing. Indeed, from this hilltop, on a clear day you can glimpse the Irish coast in the distance. And then there’s Waun Mawn itself, the remains of one of the earliest stone circles in Britain, dating to around 3300 B.C. and located within a few miles of the outcrops where the Stonehenge bluestones are now known to have originated.

Discovered in 1925 from aerial photographs of a wheat field, Woodhenge included six concentric rings of towering timbers, their locations now marked by concrete pillars. Like nearby Stonehenge, the structure was built to align with the rising sun on the summer solstice.

“For some reason they started building it and abandoned it after they got about a third of the way through,” Parker Pearson says of Waun Mawn. “We can see where they actually dug holes for additional stones but never placed them.” Of the 15 or so stones that were installed, only one remains standing. Three more are lying in the grass. The rest are missing.

THE MOVEMENT OF THE MASSIVE STONES ACROSS THE LANDSCAPE LIKELY ATTRACTED CROWDS OF FESTIVE ONLOOKERS. ‘IT WOULD HAVE BEEN LIKE WATCHING THE SPACE SHUTTLE GO BY,’ SAYS ARCHAEOLOGIST MIKE PITTS.

Last year Parker Pearson and his colleagues published a theory that the Stonehenge we know today was built in whole or in part from stones from earlier monuments in Wales that were dismantled and carried east by a migrating community around 3000 B.C. One stone in particular—number 62 in the nomenclature of Stonehenge archaeologists—could possibly be traced directly to Waun Mawn. The claim, which aired on a British TV special, created a stir in the press and divided archaeologists. Some were skeptical that Waun Mawn was a stone circle at all, but merely a few isolated stones. And so Parker Pearson returned to Waun Mawn to firm up his theory.

The evidence is certainly tantalizing. Stone 62 is one of only three bluestones at Stonehenge made of non-spotted dolerite, the type of stone used to build Waun Mawn. Moreover, stone 62 has a peculiar pentagonal cross section that appears to match the imprint left by one of the stones that were removed from the ancient Welsh circle. In addition, a stone chip found in the former socket hole suggested that the missing stone was also a non-spotted dolerite.

WEST KENNET PALISADES

A team of archaeologists and volunteers searches for clues into life at a series of huge wooden enclosures known today as the West Kennet Palisades. Artifacts from as far as 200 miles away and a profusion of charred pig bones suggest it may have been a place of festive gatherings that attracted people from many parts of Britain.

Petra Jones, a field archaeologist with Cambridge University, measures the massive footprint of a vanished post at the palisades, one of the grandest monuments that arose during the building boom. To obtain the huge timbers, woodcutters walked miles to reach deep forests. Then the real work began: A recent experiment showed that felling a single large pine required more than 11,000 blows with a flint axe.

The posthole, which held one of 4,000 massive oak timbers at the West Kennet Palisades, contains a dark stripe in the earth where a wood pillar rotted away thousands of years ago.

During their follow-up excavation, Parker Pearson and his team were able to build on evidence that Waun Mawn was indeed a stone circle and one of strikingly similar dimensions to the early ditch that ringed Stonehenge. And like Stonehenge, Waun Mawn appears to have been aligned with the solstice. However, they were unable to establish a definitive geochemical match between anything at Waun Mawn and the bluestones at Stonehenge, which might have proved their case.

But finding an exact match with any one stone was always going to be a long shot, Parker Pearson says, noting that of the 80-some bluestones, archaeologists believe once stood at Stonehenge, only 43 are present today.

“We have missing stones there and missing stones here,” he says. “But what we’ve got now is good evidence that the people who were building the circle at Waun Mawn stopped in the middle of making it. They dig a hole for the next stone and then don’t fill it. What happened? Where did they go? Where are the stones?”

Archaeological evidence—or the lack of it—suggests that few people were living at Waun Mawn after 3000 B.C., a date that dovetails nicely with the idea of a migration from Wales. “But an absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence,” says Parker Pearson, who hopes to return to the Preseli Hills to study ancient pollens that could reveal whether the grazing lands reverted to wilderness around that time. If so, the finding would add weight to his theory that the area was abandoned about the time Stonehenge was built.

And if Stonehenge’s curiously shaped stone 62 can’t be conclusively linked with the stone circle in the Preseli Hills, research by geologists Bevins and Ixer has pinpointed the outcrop from which it came, a little to the east of Waun Mawn. “It’s an outcrop that no archaeologist has looked at yet,” Bevins says. “As geologists, we can’t tell the human side of the story, but we can certainly give them a fresh place to pick up the trail.”

IT’S ABOUT A four-hour drive from Waun Mawn to Stonehenge, the last few miles of which are along the A303. This narrow, potholed, notoriously traffic-choked highway passes so close to Stonehenge the famous monument is almost a roadside attraction.

If the original builders of Stonehenge intended to create a landmark that would capture the imagination of generations to come, they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The global icon is one of Britain’s biggest tourist draws, attracting more than a million visitors a year before the COVID-19 epidemic. Virtually all of them get here on the A303, which is also a major truck artery and the road taken by millions of vacationers to popular seaside resort towns.

Stonehenge’s uprights bear witness to the long march of time and visitors. A trilithon—held together by a mortise-and-tenon joint borrowed from woodworking—wears a patina of moss and lichen.

Stonehenge’s uprights bear witness to the long march of time and visitors. A trilithon—held together by a mortise-and-tenon joint borrowed from woodworking—wears a patina of moss and lichen.IT WASN’T UNTIL RECENT YEARS THAT ANYONE REALIZED MANY OF THESE MEGA-MONUMENTS HAD BEEN BUILT AT ROUGHLY THE SAME TIME AND IN A MAD RUSH.

LEFT: Stone 60 appears to have melted over a concrete filling installed in 1959 to stabilize the upright. RIGHT: Faint traces of a dagger and axe-head likely date to the Bronze Age.

In recent decades the A303 has been upgraded to a four-lane highway for much of its length, but not the few miles on either side of Stonehenge. Constant traffic jams mean that it can take locals an hour to drive from one nearby village to another, while endless rumbling trucks detract from the experience of visiting Stonehenge.

“Everybody agrees that something needs to be done about the A303,” says Vince Gaffney, professor of landscape archaeology at the University of Bradford. “The question is, what?”

Stonehenge is the centrepiece of a 20-square-mile UNESCO World Heritage site, which in turn abuts areas of environmentally sensitive land, a military base and proving ground, and many small communities, so there are few uncontested options for rerouting the highway. A controversial proposal to build a two-mile-long, four-lane tunnel to bypass the Stonehenge site drew fire from archaeologists and sparked protests by a coalition of environmentalists and Druids. Last year Britain’s High Court found in favor of the protesters and put the $2.2 billion project on hold.

Raising a sword for peace, not war, a Druid priestess blesses the attendees during a summer solstice celebration at Stanton Drew, where the congregation includes a herd of cows. Modern versions of the religion focus on reverence for the natural world and veneration of ancestors—including the builders of Britain’s ancient monuments.

Druid Adrian Rooke communes with a standing stone at Stanton Drew. An 18th-century Anglican priest promoted the idea that Britain’s megaliths were temples built by ancient Druids, a notion now long disproved. But modern-day Druids feel a special connection to the stone circles, where they gather for rituals marking the cycle of the seasons.

Three stones called the Cove, dominate a grassy area around a pub not far from the Neolithic ceremonial center of Stanton Drew. Recent surveys indicated they stand near a burial mound a thousand years older than the rest of the site.

Three stones called the Cove, dominate a grassy area around a pub not far from the Neolithic ceremonial center of Stanton Drew. Recent surveys indicated they stand near a burial mound a thousand years older than the rest of the site.Ironically, the surprise discovery of a milewide ring of enormous pits around the nearby henge at Durrington Walls, dug by Neolithic excavators about 4,400 years ago near the peak of the building boom, played a role in thwarting the 21st-century tunnel diggers. The pits were detected in 2015 by a high-tech remote sensing survey of 3,000 acres of the Stonehenge landscape that revealed dozens of unexpected monuments.

“We noticed these strange anomalies at the time but were too busy with everything else to follow it up,” says Gaffney, who co-led the survey. “Later, when we went back, we saw we had these huge pits forming a giant arc around the henge. It was on a scale nobody had ever seen before.”

It was so huge and unexpected that when the team announced their find in 2020, their claims were met with widespread skepticism, and the house-size pits were dismissed as naturally occurring sinkholes. Additional research, however, proved the ring of pits had indeed been dug by people toward the end of the great Neolithic building boom, adding yet another layer of mystery to the era.

The tunnel proposal has divided archaeologists, with some seeing it as a workable compromise for solving the traffic bottleneck. “Sooner or later, something is going to have to be done,” says archaeologist Mike Pitts, editor of British Archaeology. “The fear is they’ll just take the easy way and widen the existing highway to four lanes, and that is something nobody wants.”

STONEHENGE

The autumn equinox brings a folk-festival vibe to Stonehenge as hundreds of visitors gather below its broad-shouldered trilithons. Aligned on the axis of the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset, the prehistoric stone circle has long been a place of seasonal celebrations. Stonehenge visitor Hanna Lingard greets the sun as a chilly dawn breaks on the morning of the autumn equinox. To protect the fabled monument from damage, most visitors are not allowed near the stones. But solstice and equinox are open-house occasions, and celebrants relish the opportunity to venture inside the stone circle.

A woman holds a crystal at sunrise over Stonehenge on the first morning of autumn, September 23, 2021, during equinox celebrations at the site.

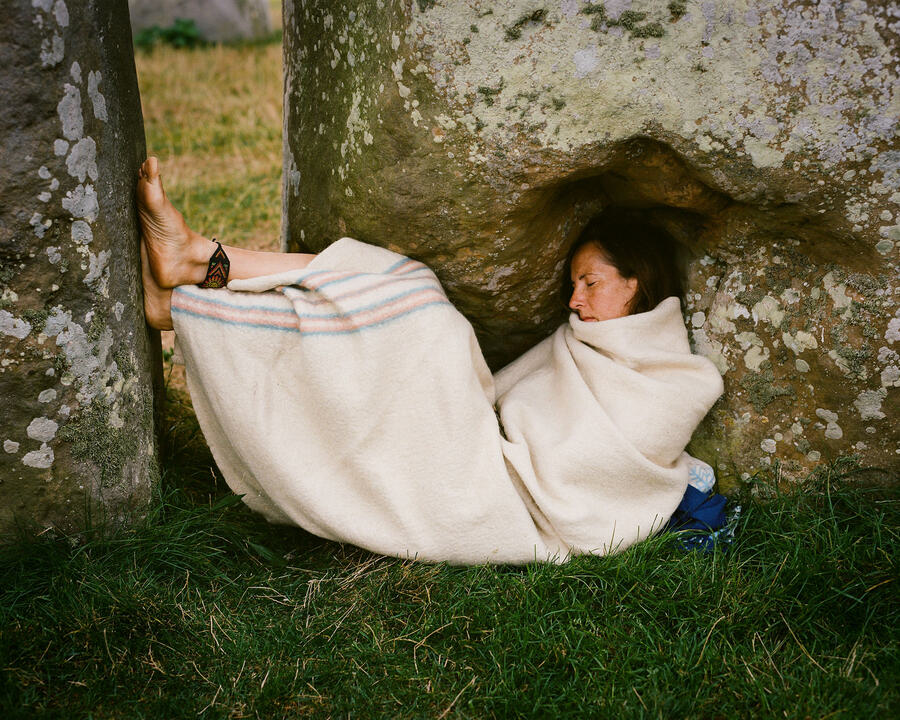

Some stones have been patched, others leave nooks for people, such as this napper on the autumn equinox, to commune closely with the site.

Some stones have been patched, others leave nooks for people, such as this napper on the autumn equinox, to commune closely with the site.

On the evening before the autumn equinox, a crowd of Druids, pagans, and pilgrims gathers to chant and celebrate the change of seasons. Says Druid Arthur Pendragon, “Stonehenge is at once a great solar clock, a pagan temple, a sacred burial site, and a place of Druid reverence and ceremony.”

As for the creators of Stonehenge, the Durrington pits, and countless other monuments, one can’t help but think they would have loved the tunnel idea, given the havoc they wreaked on their surroundings by their building binge. Britain’s ancient forests bore the brunt of it, not only in the thousands of huge oak trees felled to build those enormous palisades but also in the thousands more needed to erect Stonehenge and other megaliths. “People don’t realize the vast amount of timber that would have been required,” Pitts says.

In the case of Stonehenge, transporting dozens of huge sarsen blocks weighing on average 20 tons each for 15 miles and then erecting them on-site would have required great wooden sleds, an enormous amount of scaffolding, and possibly miles of wooden tracks over which the heavily burdened sleds could be dragged. (Contrary to popular myth, the one method they didn’t use was rollers. “Rollers just don’t work,” says Pitts, citing evidence from many experiments. “They jam up constantly.”)

Whatever the means of transport, the movement of the massive stones across the landscape likely attracted crowds of festive onlookers. “It would have been like watching the space shuttle go by,” Pitts says.

AS IMPRESSIVE as Stonehenge is, you need to drive another 20 miles to the north to the mega-henge at Avebury to grasp the sheer scale and diversity of the building boom. While Stonehenge has global name recognition and those famous sarsen trilithons, Avebury, as the 17th-century antiquarian John Aubrey put it, “does as much exceed in greatness the so-renowned Stonehenge [sic], as a Cathedral doeth a parish church.”

The Avebury henge is almost a mile in circumference, so large that nearly its entire namesake village—including a pub, thatched cottages, and pastures dotted with sheep—fits comfortably in its embrace. The stone circle within it, at more than a thousand feet in diameter, is the largest in the world. Two more circles lie inside that, and a grand avenue of standing stones leads away from it, stretching a mile and a half across the countryside to an outlying stone and timber circle. And for good measure, the eerie mass of Silbury Hill, composed of 500,000 tons of soil and the largest human-made mound in prehistoric Europe, is only a 20-minute walk away.

Hidden beneath this sleepy patch of bottomland along the River Kennet, just a mile or so downstream from Avebury, lies what Josh Pollard, a professor of archaeology at the University of Southampton, refers to as the “sleeping giants” of the Avebury landscape: a series of wooden palisades that were built from the trunks of more than 4,000 ancient oaks. During excavations last summer, Pollard and his team discovered yet another timber enclosure, some 300 feet in diameter, and within it the footings of an enormous rectangular great house more than a hundred feet long, with walls made of gigantic timbers towering as much as 40 feet above the ground. “This would have been a truly astonishing sight,” Pollard says.

Yet for all Avebury’s grandeur, and that of the other monuments nearby, it’s the River Kennet, flowing through the sleepy Wiltshire countryside a few hundred yards away, that Pollard believes to be the key to understanding the minds of the Neolithic people who built all these things.

“I think the river was more important to them than the monuments they built along it,” he says. “You can see it in the creation of Silbury at its source, and in the river’s relationship to the palisades. It has a connecting role with the monuments here just as the River Avon does with the monuments in the Stonehenge landscape.”

By the dawn of the 25th century B.C., the people of Britain surely must have been aware of the momentous technological changes unfolding on the Continent with the development of metalworking. They already may have been using copper tools acquired by trade.

“It’s hard to imagine something like the Avebury palisades being made without copper tools,” says Pollard, adding that any such tools would almost certainly have been reused and recycled many times over during the centuries that followed, making it unlikely that any will be unearthed at Neolithic building sites.

WHAT SPARKED the extraordinary building boom, and how and why it came to an end, remain unsolved mysteries. But archaeologists note an intriguing connection in time with the rise of the Bronze Age, which arrived in Britain by way of another mass migration from the Continent.

“The dates are awfully close,” says English Heritage’s Susan Greaney. “Was this splurge in monument building a reaction to the changes they knew were coming? Did they sense this was the end of the era? Or could it have been the monument building itself that caused a collapse in the society or its belief system that left a vacuum that others came to fill? Was there some kind of a rebellion against an authority that was ordering all this unsustainable construction?”

A more chilling possibility is that a pandemic may have played a role. Scientists have found plague bacillus in a Neolithic tomb in Sweden, and earlier this year it was identified in a Bronze Age grave in Somerset. The ancient variety doesn’t appear to be as virulent as the one that swept Europe in the 14th century, but there’s no telling what its effects might have been on Britain’s Neolithic people.

“It could be that unbeknownst to them, the diaspora who were on the move at the dawn of the Bronze Age were spreading an epidemic, wiping out populations and opening up new areas for people to move into,” says the University of York’s Jim Leary.

One way or another, within a century of Stonehenge’s completion, waves of genetically distinct settlers once again were coming over from the Continent. History was repeating itself a hundred generations later, except this time the newcomers’ ancestry stretched back thousands of years to the Eurasian steppes instead of to Anatolia. The so-called Beaker people brought new beliefs, new ideas, their distinctive beaker-shaped pottery, and metallurgical skills that would define the coming age.

The Neolithic farmers who built Stonehenge and scores of other monuments faded into history, their DNA all but vanishing from Britain’s gene pool. The landscape around Stonehenge would continue to be an important burial site, but the era of mega-monuments was over.

“Monument building is usually a kind of peak of a civilization,” Leary says. “But I don’t think this was the peak of a civilization. I think it was the mad, manic, final throw of the dice of a society that knows its time is up.”