Destigmatizing Drug Use Has Been a Profound Mistake

Blue America needs to send a stronger, more consistent message that hard drugs should be shunned.

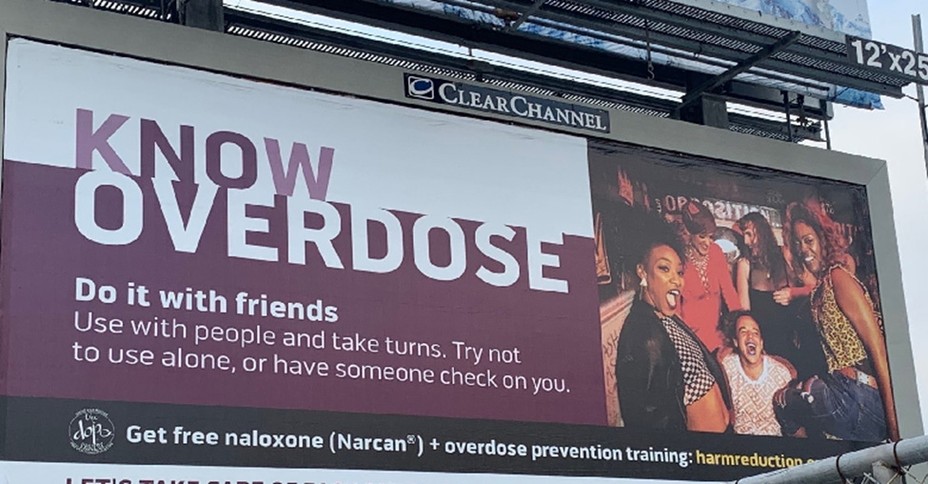

The image on the billboard that appeared in downtown San Francisco in early 2020 would have been familiar to anyone who’d ever seen a beer commercial: Attractive young people laughing and smiling as they shared a carefree high. But the intoxicant being celebrated was fentanyl, not beer. “Do it with friends,” the billboard advised, so as to reduce the risks of overdose.

The advertising campaign was part of an ongoing national effort by activists and health officials to destigmatize hard-drug use on the theory that doing so would lessen its harms. Particularly in blue cities and states, that idea is having a moment. The general message carried by the San Francisco billboard appeared as well in the New York City health department’s “Let’s Talk Fentanyl” campaign, which last year told subway riders, “Don’t be ashamed you are using, be empowered that you are using safely,” and further counseled them to “start with a small dose and go slowly.”

The nationally influential Drug Policy Alliance goes further: It lauds many fentanyl dealers as “harm reductionists” who should be respected and left alone by authorities (because the arrest of a trusted dealer might cause users to seek the drug from an unfamiliar source). A prominent subset of academics provides intellectual support for these initiatives, theorizing that stigma against drug use is ethically wrong and also worsens public health.

That so many influential people are working hard to promote a positive image of a drug that is killing 200 Americans a day is stunning, though the peculiar logic behind their efforts is not hard to understand. Many believe that policy changes have next to no ability to affect the prevalence of drug use. Some think that the government shouldn’t try to reduce use, even if it could. If the amount of drug use is beyond control, the theory goes, it is better to bring that use out of dark corners so that at least some of its dangers can be contained.

In the background is a continuing reaction to the excesses of America’s late-20th-century War on Drugs. Some of the Baby Boomers who now run many American institutions once sneered—appropriately—at the hysterical anti-marijuana messages directed at them in their youth. And although few would equate 1980s-era marijuana with fentanyl, their suspicion of drug panic lingers. They are joined in their cause by young activists who consider disapproval of drugs to be just another tendril of a racist war that aims to punish already marginalized people.

All of us, as humans, are vulnerable at times, especially those of us who live particularly hard lives. Empathy for people in the clutch of addiction is noble, and finding ways to help them is a moral necessity. But destigmatizing the use of the drugs that are destroying their life is a profoundly mistaken approach. Cultural disapproval of harmful behavior can be a potent force for protecting public health and safety—as the examples of increased stigma against drunk driving and tobacco smoking show. The maxim “Love the sinner, hate the sin” is apt when it comes to the use of the new synthetic drugs flooding the U.S. At least in some parts of the country, we need more reflexive, more visible, and more consistent rejection of drug use, not less.

The billboards and subway ads are born of the same desperation that drives some people on the other side of the political aisle to make the equally absurd suggestion that the U.S. should bomb Mexico to stop drug traffickers: None of the traditional strategies to suppress the use of drugs seems to be working for fentanyl and methamphetamine.

Deadly synthetic drugs—most notably fentanyl and meth—now dominate the hard-drug market because they are cheaper and quicker to produce than the plant-based drugs that preceded them. Traffickers don’t have to secure farmland and peasant labor as they did to cultivate poppies or coca. Seizures by law enforcement are little more than a nuisance, because the drugs can be replaced by labs overnight.

In the past, drug-law enforcement sought to limit illegal-drug supply enough to keep prices high, and thereby discourage consumption. But border guards and police have only limited power to meaningfully reduce the availability of drugs that are so quick and inexpensive to make.

Cheap, easy access to the drugs, when combined with their extraordinary potency, creates an extremely high risk of addiction and overdose. Treatment can help. But many addicted drug users don’t have easy access to treatment, and many of those who have access do not want it.

This is where the concept of harm reduction and its correlate, the destigmatization of drug use, come in. Some harm-reduction services, notably needle exchanges and ready access to the overdose-rescue medication naloxone, do greatly help those who continue to use drugs. But most other arrows in the harm-reduction quiver are much less powerful, and as a primary response to the drug crisis, harm reduction is plainly inadequate: Addiction and death rates remain appallingly high in areas that have shied away from tackling drug use and simply focused on reducing its harm.

Consider the Canadian province of British Columbia, which has gone further than just about any place else in making harm reduction the centerpiece of its drug-response strategy. It has decriminalized drugs, offers universal health care, and provides a range of health services to drug users, including clinic-provided heroin and legal distribution of powerful opioids for unsupervised use. And yet its rate of drug-overdose fatalities is nearly identical to that of South Carolina, which relies on criminal punishments to deter use, and provides little in the way of harm-reduction services to drug users.

That such radically different approaches produce the same result suggests having some modesty about the potential of harm reduction to reduce the toll of fentanyl and other synthetic drugs. And by definition, even a world-leading treatment-and-harm-reduction system helps only people who already use drugs. Because epidemics of any sort end only when the number of new cases declines, curtailing the synthetic-drug crisis depends on deterring people from using them in the first place. Destigmatizing drug use does the opposite.

Because of the limited power of law enforcement to reduce synthetic-drug availability, personal restraint and social deterrence have become essential to limiting the extent of the crisis, especially with regard to potential new users. If getting drugs is easy, the main barrier to drug use becomes people’s sense that using them is something they do not want to do and do not want people they care about to do either.

Taboos exist, in part, because they are effective. Avoiding temptations of all kinds can be easier if one thinks about those choices as being virtuous and automatic—I am not the kind of person who does this—rather than reevaluating them case by case or day by day.

Ironically, one of the best demonstrations of the power of stigma to change behavior was produced within the same public-health community that is now trying to destigmatize drug use. Cigarette smoking went from being banal and ubiquitous in the 1950s to uncommon today, one of the greatest achievements of public health. Crucial to this success was deglamorizing smoking through anti-smoking advertising campaigns (including some featuring graphic portrayals of the health effects of cigarettes), relentless recitation of the deaths smoking had caused, and a clear message that not smoking was a smarter, better choice.

Social deterrence alone will not solve the drug crisis; no single strategy will. But the power of culture to shape behavior—including addictive behavior—shows up in basic statistics. For example, Asian Americans use marijuana at less than half the national rate (9 percent versus 19 percent). Likewise, Americans who say that religion is important to them use cannabis at less than half the rate of their peers who say it is not (10 percent versus 21 percent). Gender gaps in smoking tell the story even more starkly. In Sweden, women’s smoking rates match or exceed those of men; in China, rates for men are 25 times higher than for women (about 50 percent versus 2 percent). This has nothing to do with biological differences between Swedish and Chinese women, and everything to do with the power of social approval and disapproval.

How does one change culture? Education and public-service announcements have a role. “One pill can kill” is straight talk, not hyperbole, and reminding parents to lock up their opioid painkillers is a useful caution about how deadly they can be. (There are about as many prescription-opioid deaths per prescription as there are gun deaths per gun in the U.S.)

Maintaining some modest penalties, particularly for public drug use, can help prevent use from being normalized. So can smart policing to suppress flagrant, public street markets so that the selling takes place in private, behind closed doors. In addition to making communities objectively more dangerous, public drug markets send the wrong message about the acceptability of use. And closing them can help people who want to stay away from, say, opioids avoid daily temptation, even if policing can’t stop someone determined to obtain opioids from finding them.

Socially useful pressure from the legal system can be applied in other ways, too. Addiction often drives criminal offenses—shoplifting, street harassment, vehicular burglary—that in many cities go unpunished today. Mandated treatment for offenders with addiction problems would underscore societal disapproval while also helping those people—and their families. Many anti-stigma campaigners believe that drug users should never go into treatment until they volunteer for it, but mandated treatment is roughly as effective as voluntary treatment.

Helping people who have fallen prey to powerful drugs is entirely compatible with a strong stigma against drug use—and indeed, they should go together. Sometimes genuine help involves pressure. Regardless, compassion for the people must accompany stigma against the act. Treatment options and other supports for people battling addiction should be expanded.

The historian David Musto chronicled the rise and decline of America’s first epidemic of hard-drug use. In the late 19th century, Civil War veterans were extensively treated with morphine, Coca-Cola contained cocaine, and parents gave teething babies morphine-laced patent medicines like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. Unsurprisingly, rates of drug addiction rose to distressing levels. That earlier epidemic was brought under control in part via public policy, but Musto notes that use was already declining before the laws changed. Over time, through bitter experience, people came to understand the drugs’ risks and changed their behavior to avoid them.

Tragically, in the late 1990s, certain big pharmaceutical companies underwrote an organized campaign to deny the dangers of opioids, and many, many people again used them too liberally. That failure to respect the dangerous power of these drugs was the proximate cause of the addiction that dominates the lives of the millions of North Americans who struggle with opioid-use disorder today.

Society is again learning via hard experience that drugs are dangerous. Efforts to destigmatize drug use may delay this learning, draw out the epidemic, invite new cohorts to try hard drugs, and create more addicted people. Instead, we as a society should have the wisdom to say unequivocally that in this new era of synthetic drugs, none of these drugs—nor any illegal substance, which may well contain them—should ever be used.