When in the Yucatan, I saw 19 Mayan sites. All are different, each with its charm.

Power struggles? Drought? Overpopulation? Whatever happened to the Maya remains a mystery—with clues hidden in the jungle.

At its height, during the Late Classic period (A.D. 600-900), the Maya civilization formed a constellation of kingdoms and cities that stretched across the Yucatan Peninsula and Central America, almost 125,000 square miles. Scholars estimate that there were as many as 40 Maya cities. The most important urban centers were Uxmal, Palenque, Chichén Itzá, Tikal, Copán, and Calakmul. Built during the Classic period (A.D. 200-900), the Maya’s soaring pyramid temples and grand buildings—believed by some to be palaces—were richly decorated with sacred art dedicated to the gods.

Over two centuries, major cities emptied, with their grand temples abandoned and vivid artworks unfinished. Much like its ending, the exact beginning of Maya culture has been difficult to pin down. Many scholars believe it first coalesced sometime between 7000 B.C. and 2000 B.C. after hunter-gatherers from South America moved into Mesoamerica and settled there. Sometime around 4000 B.C., cultivation of corn, their staple crop, exploded, allowing Maya culture to flourish and expand.

The Maya did not rule as a unified empire. Rather, this was a shared society. Power struggles did occur, but they were fought by rival city-states or local ajaws, or rulers. Cancún occupied a strategic position on the region’s trade routes and was linked politically with the powerful Maya city of Calakmul. Numerous inscriptions have been found on monuments, but none date to later than the year 800. In this year, the city suffered a violent attack. The royal family and other members of the nobility were murdered, and their bodies dumped, complete with their emblems of power and jadeite jewelry, into three makeshift burial spaces. In the largest one, 38 bodies with signs of brutal trauma were unearthed.

The collapse—a decline that spread from city to city—lasted more than a hundred years. It began in the region known as Petexbatún and crossed the lands near the Usumacinta River.

As cities fell like dominoes, the jungle began to claw back land from the Maya civilization. Plant roots and tendrils curled through palaces, temples, and squares.

Hidden in the jungle, the remains of Maya architecture provide intriguing insights into the speed of the collapse. One of the last buildings erected in the city of Bonampak, in the Usumacinta River region, features vivid murals showing a victorious battle fought by the ajaw in the year 791, as well as a spectacular royal ceremony. But the full artwork is unfinished. Incomplete sketches are visible on the walls, as if artists had put down their tools and walked away in the middle of their work.

An equally dramatic example was found in Yaxchilán, a city close to Bonampak. In 800, the king erected an imposing building and lavishly decorated it with sculptures. The building’s lintels, stelae, and stairs were intricately carved with royal scenes and texts. Just eight years later, the work would be abandoned. The last text found on the site was written in the year 808.

At the start of the ninth century, builders began a magnificent temple in the city of Aguateca (in modern Guatemala). But in 810, construction stopped suddenly, leaving the temple half-finished. The stelae that had been smoothed ready for carving were never adorned. Palisades and defensive fortifications were built, suggesting that the people of Aguateca perceived an external threat. A few years later, the city was deserted. Whatever struck these cities hit them quickly.The collapse had no single cause but rather a complex combination of factors, many common to individual cities. Overpopulation in Maya cities triggered this crisis by overstraining local resources. At the beginning of the ninth century, Maya civilization reached the peak of its demographic curve. Tikal, in present-day Guatemala, was the most populous of all the Maya cities and had grown to around 50,000 inhabitants. Local agriculture, even if expanded, would struggle to support the population. It’s not clear how the populations redistributed themselves after abandoning the cities.

Even more of an enigma, a century and a half later, Maya cities in the northern areas of the Yucatan Peninsula experienced a collapse that seemed to mirror the first. The city of Uxmal during the 10th century had become the main center of power in the Puuc region. An enormous palace served as both a royal residence where the nobility held councils. There was also a ball court, and a ceremonial complex called the Nunnery Quadrangle. The reliefs, paintings, and inscriptions from this period evoke scenes of war, with warriors decked out in full battle regalia and prisoners being sacrificed.

Uxmal faced a dramatic decline in the 11th century. Construction on several monumental works was never completed. The immediate cause of this crisis appears to have been the expansion of the neighbouring city of Chichén Itzá. In parallel, the eastern region of Puuc became increasingly depopulated until it was totally abandoned by the beginning of the 11th century.

This collapse meant the end of a political and economic system and the abandonment of cities across the southern lowlands. The cities of the northern lowlands also were abandoned 150 years later.

The Maya civilization never recovered, at least in the form it had once known. However, the descendants of Maya nobles, priests, warriors, and farmers today inhabit the same lands as their ancestors and perpetuate their culture in the still-spoken Indigenous languages and religious rituals. Ancestral farming practices have not been forgotten, nor have traditional styles of clothes and jewelry. Although the Maya collapse seemed to spell the end for the Maya civilization, Maya culture continues to thrive.

An illustration of Aguateca as it may have appeared in the eighth century The twin cities of Dos Pilas and Aguateca stood on a high plateau above Lake Petexbatún (modern Petén, Guatemala). To augment their natural defences, the cities were fortified to prevent enemy attacks. Stockades protected the temples, palaces, fields, and the water supply. Despite these precautions, Aguateca was attacked in 790, the date on its last known stela.

For the next three sites, I drove to Frontera Corazal, a small riverside frontier town on the Usumacinta River that forms the boundary between Mexico and Guatemala. This is the largest river between Texas and Venezuela and discharges 105 billion cubic metres of water into the Gulf of Mexico each year. We boarded long outboard-powered launches to travel 32 km down the Usumacinta to Yazchitlan and Bonampak.

YAZCHILAN, Mexico. A Mayan ruin in a terrific jungle setting above a horseshoe loop of the river. Howler monkeys were roaring throughout the visit and were frequently visible. Besides the setting, Yaxchilan is famed for its ornamental building facades and roof combs, and its very nice stone lintels carved on their undersides with conquest and ceremonial scenes. Compared to Palenque, this site was very simple with minimal reconstruction. The city peaked in power from AD 681 to 800 and was abandoned by 810.

BONOMPAK Mexico. It was discovered in 1946. A small site, it is famous for its full-colour murals depicting prisoner sacrifices, bloodletting, and dancing to celebrate the consecration of a new infant heir – quite spectacular.

We returned to Frontera to take the same launches upstream 13 km and entered Guatemala. Flores was a long 3-hour drive on rough roads. It is a small touristy community located on an island in the middle of a lake.

TICAL, Guatemala. Tical was seen on a sunrise tour. We left Flores at 3:30 am to drive the 60 km to the ruin. We watched the sunrise from the top of Temple 1V, the highest temple in Mesoamerica. With other temples looming out of the jungle and howler monkeys roaring, it was a unique experience. Above the thick tree roots of the Petén jungle rises Temple V, at 187 feet high, built around A.D. 600. The other temples around the Grand Plaza have been 90% reconstructed and are impressive pyramids with very steep sides and tall white temples on top. The nicest stela is now on display in the British Museum and Switzerland. We saw many toucans, white-faced parrots, and another tropical bird with a yellow tail and orange beak not listed in my Sibley’s bird book. The entrance fee to Tikal is $24, four times the price of any other Mayan site.

This pyramid was erected in 734 in the Great Plaza of Tikal to house the remains of ruler Jasaw Chan K’awiil I. Like other Maya cities, Tikal was abandoned around the year 900.

CALAKMUL. In Campeche State 60 km south of the highway, the road deteriorated to one lane with many low trees. Calakmul is believed to have been the largest city-state in the Mayan world with 60,000 people at its height from 300-700 AD. 6,750 structures have been mapped to date. Its tallest pyramid at 173.8 feet high had a footprint of five acres. Its 120 stelae are dated 495 to 909 AD and are the most of any Mayan site – the ones still present are heavily eroded.

Balamku. Much smaller than Calakmul, it is renowned for a fantastic, huge stucco frieze found inside a ruined pyramid in 1990. The many anthropomorphic creatures still have much of the original colour visible.

Kohunlich Temple of Masks features haunting masks with star-incised eyes, mustaches and nose plugs. 6.6 feet tall, these masks are a rarity. The ruins are in a nice jungle setting.

Tulum is famous for its ruins. After paying 50 pesos to park and 48 pesos to enter, this is the worst Mayan site I visited but it was also the busiest with thousands of people on large tours with guides. It’s longer walking from the parking lot to the ruin than to see the ruin. The only saving grace is the location on a beach and the few iguanas wandering around.

Coba was another ruin that I should have missed. With a 50 peso parking fee (the only ruins that charge for parking are near Cancun), the OK ruins were each separated by long distances requiring bicycle taxis and rental bicycles. All the stelae were completely eroded.

Ek Balam is a small site with a well-preserved stucco mural with beautiful angel-like winged figures unique in Mayan art.

CHICHEN ITZA is one of the finest Mayan sites. Not abandoned till 1200 AD, it is one of the “newest”, and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The ruins surround a breathtaking pyramid, El Castille. Each of the four sides has 91 steps plus the platform on top makes 365. At the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun lights up a bright serpent pattern on the wall supporting the north staircase. There is the Group of a Thousand Columns and the Temple of the Warriors, many with carved columns, a huge ball court and the observatory that allowed celestial sightings used to keep their elaborate calendar system.

It was common for the Maya to merge their interests in astronomy and building as in Chichen Itza’s Kukulcan Temple. When the sun’s rays illuminate the pyramid during the spring equinox, a huge serpent-like image is seen between the shadows. The stone snake head was lit by the sun with a body leading up the staircase.

South of Merida, all the ruins are in the Puuc style (puuc is Mayan for “hilly area” in this pancake-flat area of the Yucatan) – thin squares of limestone veneer, decorated cornices, boot-shaped vault stones, rows of attached half columns and heavily decorated upper facades. Most were at their peak from 750-1000 AD. Most structures are adorned with hundreds of stone masks and carvings representing the rain god, Chac-Mool, easily identified by his prominent hooked nose.

Labna has a large palace with many chultunes, a building with a large roof comb and a beautiful arch with ornate carvings.

Xlapak is small.

Sayil has a 160-foot-long palace with columns and rich carvings of Chac, and a human phallic figure. One chultune holds 7000 gallons of water.

Kabah’s most ornate building’s west side has 250 Chac masks with elaborate curved noses. A large arch marking the end of the 20 km long elevated road or sacbe extended from Kabah to Uxmal.

UXMAL is one of the top Mayan sites. Most buildings are made of hard pink limestone and have been all reconstructed (if not reconstructed, most of these sites would look like piles of rubble covered in the jungle). It has two large pyramids and all buildings have intricate, geometric mosaics sweeping across the upper parts of elongated facades. Chac’s image is everywhere as stucco masks protruding from facades and cornices. Uxmal thrived between the sixth and tenth centuries and was among the finest examples of Maya architecture. The Governor’s Palace was erected during the tenth century. It stands on a huge rectangular platform more than 200 yards long.

Uxmal was my last and favourite Mayan site.

LAMANAI Belize

From Orange Walk, it was 50 miles down the New River. Many birds and crocodiles were seen and we passed a large Mennonite town. The ruins were great with some large pyramids and many howler monkeys. With the largest voice box of any animal for its size, the roar can be incredible. On the way back up the river, the young boat driver took the many corners at high speed, great fun.

ATM CAVE (Actun Tunichil Muknal). Belize

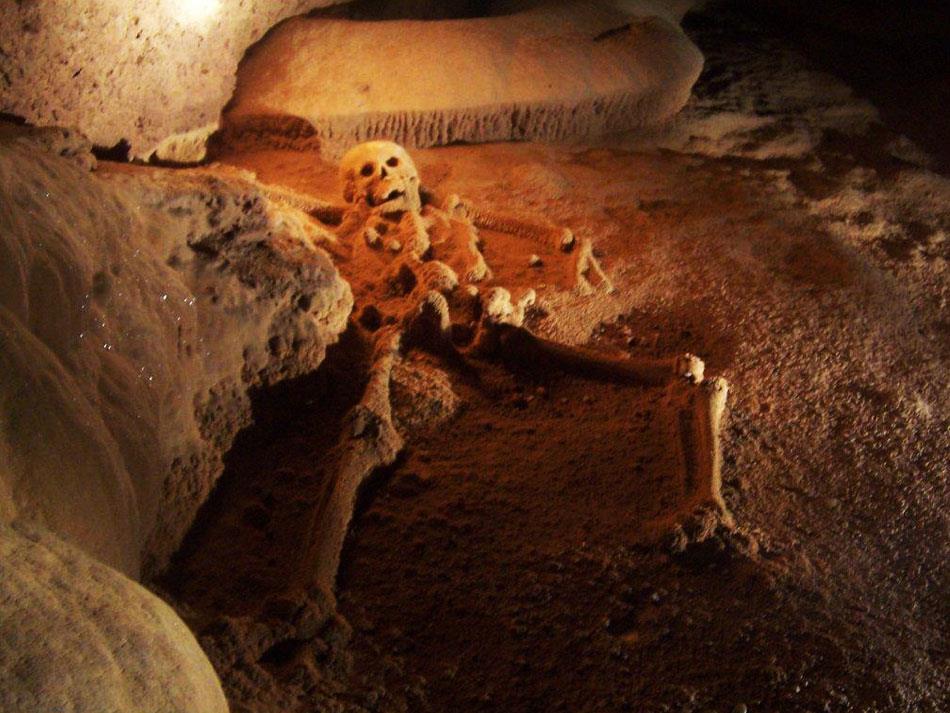

With a running river in the cave, there were two swims and lots of wading, some up to your chest. The formations in the cave were pristine. After ½ km in the river, we climbed up into a fantastic Mayan ceremonial cave.

Hundreds of broken pots lined the walls and were cemented into the floors by the mineralized water. There were several skeletons including one of a hydrocephalic child. 98% of the artifacts have been left intact, making it one of the most authentic archaeological sites in the world, Opened to the public only in 1997, it has been well protected and can only be visited with a guide.

One covered pyramid, the Rosalia temple, was completely intact and an exact replica has been reconstructed inside the impressive museum. You enter a serpent’s mouth and then walk down its gullet to enter the huge space. Copan is best known for its many stelae, many in excellent shape with clear hieroglyphics and red paint still visible. The hieroglyphic stairway tells the story of the 16 rulers of Copan. Since crossing into Honduras, there is no evidence of Mayans in traditional dress – the men all wear cowboy boots and hats.

However, and in common with other Mesoamerican societies, the repetition of the various calendric cycles, the natural cycles of observable phenomena, and the recurrence and renewal of death-rebirth imagery in their mythological traditions were important influences upon Maya societies. This conceptual view, in which the “cyclical nature” of time is highlighted, was a pre-eminent one, and many rituals were concerned with the completion and re-occurrences of various cycles. As the particular calendric configurations were once again repeated, so too were the “supernatural” influences with which they were associated. Thus it was held that particular calendar configurations had a specific “character” to them, which would influence events on days exhibiting that configuration. Divinations could then be made from the auguries associated with a certain configuration since events taking place on some future date would be subject to the same influences as their corresponding previous cycle dates. Events and ceremonies would be timed to coincide with auspicious dates and avoid inauspicious ones.

The completion of significant calendar cycles (“period endings”), such as a k’atun-cycle, were often marked by the erection and dedication of specific monuments (mostly stela inscriptions, but sometimes twin-pyramid complexes such as those in Tikal and Yaxha), commemorating the completion, accompanied by dedicatory ceremonies.

A cyclical interpretation is also noted in Maya creation accounts, in which the present world and the humans in it were preceded by other worlds (one to five others, depending on the tradition) that were fashioned in various forms by the gods, but subsequently destroyed. The present world also had a tenuous existence, requiring the supplication and offerings of periodic sacrifice to maintain the balance of continuing existence.

Tzolk’in

The tzolk’in is the name commonly employed by Mayanist researchers for the Maya Sacred Round or 260-day calendar. The word tzolk’in is a neologism coined in Yucatec Maya, to mean “count of days”.

The tzolk’in calendar combines twenty day names with the thirteen numbers of the trecena cycle to produce 260 unique days. It is used to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events and for divination. Each successive day is numbered from 1 up to 13 and then starting again at 1. Separately from this, every day is given a name in sequence from a list of 20-day names:

Some systems started the count with 1 Imix’, followed by 2 Ik’, 3 Ak’b’al, etc. up to 13 B’en. The trecena day numbers then start again at 1 while the named-day sequence continues onwards, so the next days in the sequence are 1 Ix, 2 Men, 3 K’ib’, 4 Kab’an, 5 Etz’nab’, 6 Kawak, and 7 Ajaw. With all twenty named days used, these now began to repeat the cycle while the number sequence continues, so the next day after 7 Ajaw is 8 Imix’. The repetition of these interlocking 13- and 20-day cycles therefore takes 260 days to complete (that is, for every possible combination of number/named day to occur once).

Haab’ The Haab’ was the Maya solar calendar made up of eighteen months of twenty days each plus a period of five days (“nameless days”) at the end of the year known as Wayeb’. The five days of Wayeb’, were thought to be a dangerous time. During Wayeb, portals between the mortal realm and the Underworld dissolved. No boundaries prevented the ill-intending deities from causing disasters. To ward off these evil spirits, the Maya had customs and rituals they practiced during Wayeb’. For example, people avoided leaving their houses and washing or combing their hair. It is estimated that the Haab’ was first used around 550 BC with a starting point of the winter solstice.

Each day in the Haab’ calendar was identified by a day number in the month followed by the name of the month. Day numbers began with a glyph translated as the “seating of” a named month, which is usually regarded as day 0 of that month, although a minority treat it as day 20 of the month preceding the named month. In the latter case, the seating of Pop is day 5 of Wayeb’. For the majority, the first day of the year was 0 Pop (the seating of Pop). This was followed by 1 Pop, 2 Pop as far as 19 Pop then 0 Wo, 1 Wo and so on.

As a calendar for keeping track of the seasons, the Haab’ was a bit inaccurate, since it treated the year as having exactly 365 days, and ignored the extra quarter day (approximately) in the actual tropical year. This meant that the seasons moved with respect to the calendar year by a quarter day each year so that the calendar months named after particular seasons no longer corresponded to these seasons after a few centuries. The Haab’ is equivalent to the wandering 365-day year of the ancient Egyptians.

Calendar Round. A Calendar Round date is a date that gives both the Tzolk’in and Haab’. This date will repeat after 52 Haab’ years or 18,980 days, a Calendar Round. For example, the current creation started on 4 Ahau 8 Kumk’u. When this date recurs it is known as a Calendar Round completion.

Arithmetically, the duration of the Calendar Round can be explained in various ways. One way is to consider that the least common multiple of 260 and 365 is 18980 (73 X 260 Tzolk’in days equalling 52 X 365 Haab’ days). Not every possible combination of Tzolk’in and Haab’ can occur.

Year Bearer

A “Year Bearer” is a Tzolk’in day name that occurs on the first day of the Haab’. If the first day of the Haab’ is 0 Pop, then each 0 Pop will coincide with a Tzolk’in date, for example, 1 Ik’ 0 Pop. Since there are twenty Tzolk’in day names and the Haab’ year has 365 days (20*18 + 5), the Tzolk’in name for each succeeding Haab’ zero day will be incremented by 5 in the cycle of day names like this: 1 Ik’ 0 Pop

2 Manik’ 0 Pop

3 Eb’ 0 Pop

4 Kab’an 0 Pop

5 Ik’ 0 Pop… Only these four of the Tzolk’in day names can coincide with 0 Pop, and these four are called the “Year Bearers”.

“Year Bearer” literally translates a Mayan concept. Its importance resides in two facts. For one, the four years headed by the Year Bearers are named after them and share their characteristics; therefore, they also have their own prognostications and patron deities. Moreover, since the Year Bearers are geographically identified with boundary markers or mountains, they help define the local community.

The classic system of Year Bearers described above is found at Tikal and in the Dresden Codex. During the Late Classic period, a different set of Year Bearers was in use in Campeche. In this system, the Year Bearers were the Tzolk’in that coincided with 1 Pop. These were Ak’b’al, Lamat, B’en and Edz’nab.

Example of Long Count Calendar

The east side of stela C, Quirigua with the mythical creation date of 13 baktuns, 0 katuns, 0 tuns, 0 uinals, 0 kins, 4 Ahau 8 Cumku – August 11, 3114 BCE in the proleptic Gregorian calendar.

Since Calendar Round dates repeat every 18,980 days, approximately 52 solar years, the cycle repeats roughly once each lifetime, so a more refined method of dating was needed if history was to be recorded accurately. To specify dates over periods longer than 52 years, Mesoamericans used the Long Count calendar.

The Maya name for a day was k’in. Twenty of these k’ins are known as a winal or uinal. Eighteen winals make one tun. Twenty tuns are known as a k’atun. Twenty k’atuns make a b’ak’tun.

The Long Count calendar identifies a date by counting the number of days from the Mayan creation date 4 Ahaw, 8 Kumk’u (August 11, 3114 BC in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian calendar). But instead of using a base-10 (decimal) scheme like Western numbering, the Long Count days were tallied in a modified base-20 scheme. Thus 0.0.0.1.5 is equal to 25, and 0.0.0.2.0 is equal to 40. As the winal unit resets after only counting to 18, the Long Count consistently uses base-20 only if the tun is considered the primary unit of measurement, not the k’in; with the k’in and winal units being the number of days in the tun. The Long Count 0.0.1.0.0 represents 360 days, rather than the 400 in a purely base-20 (vigesimal) count.

There are also four rarely used higher-order cycles: piktun, kalabtun, k’inchiltun, and alautun.

Since the Long Count dates are unambiguous, the Long Count was particularly well suited to use on monuments. The monumental inscriptions would include the 5 digits of the Long Count but also the two tzolk’in characters followed by the two haab’ characters.

Misinterpretation of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar was the basis for a popular belief that a cataclysm would occur on December 21, 2012. December 21, 2012, was simply the day that the calendar went to the next b’ak’tun, at Long Count 13.0.0.0.0. The date on which the calendar will go to the next piktun (a complete series of 20 b’ak’tuns), at Long Count 1.0.0.0.0.0, will be on October 13, 4772.

For the ancient Maya, it was a huge celebration to make it to the end of a whole cycle”. The portrayal of December 2012 as a doomsday or cosmic-shift event is” a complete fabrication and a chance for people to cash in.

Table of Long Count units

| Long Count Unit | Long Count Period | Days | Approximate Solar Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 K’in | 1 | ||

| 1 Winal | 20 K’in | 20 | |

| 1 Tun | 18 Winal | 360 | 1 |

| 1 K’atun | 20 Tun | 7.200 | 20 |

| 1 B’ak’tun | 20 K’atun | 144,000 | 394 |

| 1 Piktun | 20 B’ak’tun | 2,880,000 | 7,885 |

| 1 Kalabtun | 20 Piktun | 57,600,000 | 157,704 |

| 1 Kinchiltun | 20 Kalabtun | 1,152,000,000 | 3,154,071 |

| 1 Alautun | 20 K’inchiltun | 23,040,000,000 | 63,081,429 |

Supplementary Series

Many Classic period inscriptions include a series of glyphs known as the Supplementary Series. The Supplementary Series most commonly consists of the following elements:

1. Lords of the Night

Each night was ruled by one of the nine lords of the underworld. This nine-day cycle was usually written as two glyphs: a glyph that referred to the Nine Lords as a group, followed by a glyph for the lord that would rule the next night.

2. Lunar Series

A lunar Series is written as five glyphs that provide information about the current lunation, the number of the lunation in a series of six, the current ruling lunar deity and the length of the current lunation.

Moon age. The Maya counted the number of days in the current lunation. They used two systems for the zero date of the lunar cycle: either the first night they could see the thin crescent moon or the first morning when they could not see the waning moon. The age of the moon was depicted by a set of glyphs that Mayanists coined glyphs D and E:

A new moon glyph was used for day zero in the lunar cycle.

D glyphs were used for lunar ages for days 1 through 19, with the number of days that had passed from the new moon.

For lunar ages 20 to 30, an E glyph was used, with the number of days from 20.

Lunation number and lunar deity

The Maya counted the lunation in a cycle of six, numbered zero through 5. Each one was ruled by one of the six Lunar Deities. This was written as two glyphs: a glyph for the completed lunation in the lunar count with a coefficient of 0 through 5 and a glyph for the lunar deity that ruled the current lunation. Teeple found that Quirigua Stela E (9.17.0.0.0) is lunar deity 2 and that most other inscriptions use this same moon number. It is an interesting date because it was a k’atun completion and a solar eclipse was visible in the Maya area two days later on the first unlucky day of Wayeb’.

Lunation length

The length of the lunar month is 29.53059 days so if you count the number of days in a lunation it will be either 29 or 30 days. The Maya wrote whether the lunar month was 29 or 30 days as two glyphs: a glyph for lunation length followed by either a glyph made up of a moon glyph over a bundle with a suffix of 19 for a 29-day lunation or a moon glyph with a suffix of 10 for a 30-day lunation.

819 day count. Some Mayan monuments include glyphs that record an 819-day count in their Initial Series. Each group of 819 days was associated with one of the four directions and its colour — east red, north white, west black and south yellow.

The 819-day count can be described in several ways: Most of these are referred to using a “Y” glyph and a number. Many also have a glyph for K’awill — the god with a smoking mirror in his head. K’awill has been suggested as having a link to Jupiter. The accompanying texts begin with a directional glyph and a verb for 819-day-count phrases.

Short Count. During the late Classic period, the Maya began to use an abbreviated short count instead of the Long Count. An example of this can be found on altar 14 at Tikal. In the kingdoms of Postclassic Yucatán, the Short Count was used instead of the Long Count. The cyclical Short Count is a count of 13 k’atuns (or 260 tuns), in which each k’atun was named after its concluding day, Ahau (‘Lord’). 1 Imix was selected as the recurrent ‘first day’ of the cycle, corresponding to 1 Cipactli in the Aztec day count. The cycle was counted from katun 11 Ahau to katun 13 Ahau, with the coefficients of the katuns’ concluding days running in the order 11 – 9 – 7 – 5 – 3 – 1 – 12 – 10 – 8 – 6 – 4 – 2 – 13 Ahau (since a division of 20 × 360 days by 13 falls 2 days short). The concluding day 13 Ahau was followed by the re-entering first day 1 Imix. This is the system as found in the colonial Books of Chilam Balam.

Venus cycle. Another important calendar for the Maya was the Venus cycle. The Maya kings had skilled astronomers who accurately calculated the Venus cycle. The Maya achieved such accuracy by careful observation over many years. Venus was often referred to as “The Morning Star” and “The Evening Star” because of its visibility during both times. There are various theories as to why the Venus cycle was important for the Maya. Across Mesoamerica, Venus was often depicted as “defeating” the Sun and the Moon, perhaps because of its persistent visibility after transitions from day to night (and vice-versa). Most scholars agree that Venus was associated with war and that the Mayans used it to divine good times (electional astrology) for their coronations and wars. Maya rulers planned for wars to begin when Venus rose.