LEPTIS MAGNA (“Great City”), Libya. 130 km from Tripoli, it was originally a Phoenician trading port from about 700 BC and prospered for nearly 1000 years before Vandal invasions and sandstorms brought its downfall. In its heyday during the reign of Libyan Emperor Septimius Severus (145-203 AD, born in Leptis Magna, emperor from 185-203, died in York England), it was second only to Rome and housed over 100,000 people. It was abandoned in the seventh century and was buried under layers of sand until excavated in the early 20th century. Only 30% has been excavated – the rest lies under 10-20 feet of sand.

The site is one of the most spectacular and unspoiled Roman ruins in the Mediterranean The most impressive for me was the forum and the spectacular Cipollino (“onion-stone”) marble columns, quarried on the Greek island of Euboea, It has a white-green base, with thick wavy green ribs. It was principally used for column shafts, but not often for sculpture as it did not carve well.

Arch of Septimius Severus (most inscriptions have been replaced but it is still very impressive. It was a symbol of the property of the ancient town in the second century. Hadrian’s Baths. A huge bath where the sandstone walls are covered with a layer of clay, then marble to make them waterproof. The toilet was large with marble benches, and running water.

Collonaded Street.

SABRATHA. WHS dating to 500 BC. The 175 AD Theatre has a large forty-three-meter stage and holds 5,000 spectators. Also baths, temples, and the spectacular amphitheatre housed up to 10,000 spectators. City damaged in the fourth-century earthquake. Rebuilt to become one of the most popular tourist attractions in Libya today.

Arch of Marcus Aurelius, Tripoli. By the later 2nd century AD, Oea was conquered by the Romans who included it in their province of Africa. It was built in 165 AD to their emperor, Marcus Aurelius, and to Lucius Verus, the emperor’s adoptive brother, to commemorate his victories during the Roman-Parthian War of 161-166 AD.

It is Tripoli’s most impressive ancient monument at the intersection of the city’s main streets and the exact centre of the Roman city. Marcus Aurelius is riding triumphantly in his chariot. At various times in its history, it has been incorporated into a Roman forum, a storehouse, stables, a shop, a public house, and a cinema. The base of the arch is now 10 feet below street level.

MERIDA. Spain

The most impressive and extensive Roman ruins in all of Spain. Teatro Romano: built 16 BC and sat 6,000 with Corinthian stone columns and a stage façade. Puente Romano: 792m bridge with 60 granite arches. Arco de Trajano. Templo de Diana. Circo Romano: hippodrome for 30,000 spectators. Acueducto de Los Milagros: aqueduct. Museo Nacional de Arte Romano: superb collection. Alcazaba: large Muslim fort built in 835 over Roman and Visigoth forts.

BAALBEK. Lebanon

Known as Helipolis or ‘Sun City’ of the ancient world, its ruins are the most impressive ancient site in Lebanon. The temples are extravagant and built to a scale that outshone anything in Rome. Baalbek became a Roman colony in 15 BC.

The Temple of Jupiter, completed around AD 60, it was built on a massive substructure about 48x88m on a 12m high podium. It incorporated some of the largest building blocks ever used. It is the largest temple ever constructed in the Roman Empire. Today the remaining six standing columns are what is left of 19 columns on each side and 10 on each end. They are 20m high, 2m in diameter and 62 tons each in weight. All these massive blocks were moved using Lewis holes: 20-30cm deep and 4cm wide holes wider at the bottoms than the top into which Lewis pins, a hinged, metallic, trapezoidal structure was inserted. Each pin could lift 5 tons. The temple was never completed.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, a massive courtyard was constructed in front of the Temple of Jupiter, and in front of that a hexagonal courtyard on a 7m podium. The cult of Jupiter Heliopolitanus made sacrifices on 2 alters, and were destroyed and replaced by a Byzantine church

Bacchus Temple. Although there are no inscriptions to indicate the identity of the worshipped deity or date of completion, unlike the Temple of Jupiter, it was finished, likely in the 2nd century. It has 8 columns on one end and 16 on each side supporting an 18m high ceiling. It has lovely Corinthian decoration with acanthus leaf capitals and cornices. It is almost completely preserved having survived several earthquakes, several religious changes from paganism to Christianity and Islam and conversion to a dungeon in the medieval period.

Roman Quarry. A kilometre from the ruins is the quarry where most of the rock came from. Lying on its side is Hajjar al Hebla (“stone of the pregnant”), a 21×4.5×4.2m block that weighs 992 tons. However, it is not the biggest. The Western Megalith (trilithon), the base of the podium of the Temple of Jupiter is 20×4.8×4.6m and 1110 tons; but the biggest is 19.6×6.1×5.6m, 1673 tons and recently discovered. They were moved on rollers on a 15.2° incline using 16 groups of 32 men each (512 total) using clamps, ropes, capstans and 4 pulleys per group.

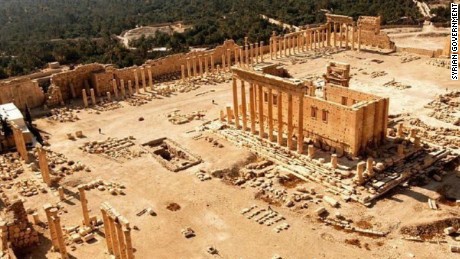

PALMYRA, Syria

By the third century AD Palmyra had become a prosperous regional center. It reached the apex of its power in the 260s when the Palmyrene King Odaenathus defeated Persian Emperor Shapur I. The king was succeeded by regent Queen Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the Palmyrene Empire. Before AD 273, Palmyra enjoyed autonomy and was attached to the Roman province of Syria, having its political organization influenced by the Greek city-state model during the first two centuries AD.

In 273, Roman emperor Aurelian destroyed the city, which was later restored by Diocletian at a reduced size. The city became a Roman colonia during the third century, leading to the incorporation of Roman governing institutions.

The Palmyrenes converted to Christianity during the fourth century and to Islam in the centuries following the conquest by the 7th-century Rashidun Caliphate, after which the Palmyrene and Greek languages were replaced by Arabic.

Palmyra became a minor center under the Byzantines and later empires. Its destruction by the Timurids in 1400 reduced it to a small village. Under French Mandatory rule in 1932, the inhabitants were moved into the new village of Tadmur, and the ancient site became available for excavations.

During the Syrian Civil War in 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) destroyed large parts of the ancient city, which was recaptured by the Syrian Army on 2 March 2017.

Location. Palmyra lies 215 km (134 mi) northeast of the Syrian capital, Damascus, in an oasis surrounded by palms (of which twenty varieties have been reported). Two mountain ranges overlook the city.

Before the war and destruction by ISIS, the temple showed a remarkable synthesis of ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman architecture.

Temple of Bel (Baal). The walls of the Temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century AD.

The temple remains lay inside a large precinct lined by porticos. It had a rectangular shape oriented north-south. It was based on a paved court surrounded by a massive 205-metre (673 ft) long wall with a propylaeum.

On a podium in the middle of the court was the actual temple building. The cella was surrounded by a prostyle of Corinthian columns and was unique with two inner sanctuaries dedicated to the shrines of Bel and other local deities. The cella was lit by two pairs of windows cut high in the two long walls.

The northern chamber was known for a bas-relief carving of the seven planets known to the ancients surrounded by the twelve signs of the Zodiac and the carvings of a procession of camels and veiled women. Stairwells to rooftop terraces were in three corners,

In the court were the remains of a basin, an altar, a dining hall, and a building with niches. In the northwest corner lay a ramp along which sacrificial animals were led into the temple area. There were three monumental gateways, of which the entry was through the west gate.

All but the front portal are destroyed.

Great Colonnade (Cardo Maximus) was Palmyra’s 1.1-kilometre-long main street., which extended from the Temple of Bel in the east, to the Funerary Temple no.86 in the city’s western part. A grand double row of columns with a roof stood inside the exterior wall. All of the roofs and most of the outside row of columns were destroyed by ISIS.

A monumental arch sat at in the middle of the Cardo Maximusin where the street makes a 32º angle turn. It served as the central “square” of the street. The Tetrapylon stands in its center. The other main street crosses at the Tetrapylon. It was erected by Diocletian at the end of the third century. It was a square platform with each corner having a grouping of four columns. Most of the columns dated to the second century AD and each was 9.50 metres high. Each column group supported a 150-ton cornice. The original columns were brought from Egypt and carved out of pink granite. This was almost totally destroyed by ISIS. Only 4 concrete columns remain. The arches are no more.

Funerary Temple no.86 built in the third century AD is located at the western end of the Great Colonnade. It was and has a portico of six columns and is the only tomb inside the city’s walls.

Byzantine churches include Palmyra’s largest church is dated to the Justinian age, its columns are 7 metres high, and its base is 27.5 by 47.5 metres.

Baths of Diocletian built by Sosianus Hierocles (the Roman governor of Syria) is on the Cardio Maximus was ruined and didn’t survive above the foundations. The complex’s entrance had four massive Egyptian granite columns each 1.3 metres in diameter, 12.5 metres high and weighing 20 tonnes.

Theatre. The seats, the lower tier of the stage with its great columns and the orchestra pit with its surrounding 1m high semi-circular wall are still intact.

![]()

The Senate building is largely ruined.

Agora of Palmyra was built in the second half of the first century AD and resembled an Eastern caravanserai more than a hub of public life. It is a massive 71 by 84 metres structure with 11 entrances. Inside the agora are 200 columnar bases that used to hold statues of prominent citizens – the eastern side for senators, the northern side for Palmyrene officials, the western side for soldiers and the southern side for caravan chiefs.

The Triclinium of the Agora was decorated with Greek key motifs running in a continuous line halfway up the wall.

The Tariff Court’s entrance was blocked by a defensive wall. It has a 5-meter stone slab that had the Palmyrene tax law inscribed on it.

The following temples stand to the south and west of Cardo Maximus.

Temple of Baalshamin (built in AD 115, and rebuilt in AD 131. Temple of Nabu (ruined). Temple of Al-lāt (largely ruined, had a giant lion relief – the Lion of Al-lāt was a relief protruding from the temple compound’s wall).

Temple of Baal-hamon (ruins located on the top of Jabal al-Muntar hill)

Destruction by ISIS

On 13 May 2015, ISIS took only 5 days to capture the city and the World Heritage Site several days later. In May and June, ISIL destroyed the tomb of Mohammed bin Ali in a mountainous region 5kms north of Palmyra (a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad’s cousin Ali, and a site revered by Shia Muslims, and the tomb of Nizar Abu Bahaaeddine, a Sufi scholar who lived in Palmyra in the 16th century.

Days after the militants had gathered the citizens and promised not to destroy the city’s monuments, ISIL destroyed the Lion of Al-lāt and other statues (23 May 2015), and the Temple of Baalshamin (23 August 2015),

The magnificent cella of the Temple of Bel stood on a podium in the middle of the enclosure. On 30 August 2015, it was dynamited using 12 tons of explosives and now is a mass of fractured rock, except for the front portal which is damaged but still standing. On 30 August 2015, ISIL destroyed the cella of the Temple of Bel. The temple’s exterior walls and entrance arch remain.

Three of the best preserved tower tombs including the Tower of Elahbel (4 September 2015), buildings with no religious meaning, including the monumental arch (5 October 2015), tetrapylon was badly damaged and part of the theater (20 January 2017).

In March 2017, the Syrian Army recaptured Palmyra. 20–30% of it is seriously damaged.

Restoration is postponed until the violence in Syria ends. The Lion of Al-lāt took two months to restore in 2017. The Arc of Triumph can be rebuilt and it might be possible to restore 98% of the site”.

My Experience. Palmyra was the highlight of my Syria trip. It was one of the most intact temples in the world.

When we drove into the city on November 9th, 2019, it was almost destroyed. I didn’t see an undamaged building. A few shops had opened in some of the bottom floors of a few of the damaged buildings. A few residents were in the main street but the rest was completely abandoned.

We went to the museum first.

Museum of Palmyra. ISIS also destroyed everything inside. The valuable funerary busts had all been removed and sent to Damascus, but all larger stone statues had their faces and hands damaged and heads broken off. The glass display cases and the great model of the city were destroyed. There were 3 mosaics on the walls that appeared intact. Two wonderful stone reliefs from the museum were recovered at the Syrian/Turkey border and were being sold by ISIS.

The site is huge with a sea of columns. All the hundreds of columns had a stone platform projected from the column at about 5m above ground. Each held a statue of a prominent god or citizen of the city but I only saw one statue remaining.

BOSRA ROMAN THEATRE, Syria

Constructed in the 2nd century probably under Trajan, it is the only monument of this type with its upper gallery in the form of a covered portico that has been integrally preserved. It was fortified between 481 and 1231.

Cross the moat on a stone bridge to enter the corridor of the fortress that makes four 90° turns. This massive stone fortress completely encompasses the theatre. It has several large square bastions.

The theatre is almost completely intact, easily the most complete Roman theatre in the world. It held 15,000 in three tiers of still intact seats accessed from multiple arcades, so efficient that the theatre could be emptied in 15 minutes. These arcaded stairs have wonderful successive arches. Columns topped by capitals are still present on about ¼ of the top circumference.

The most spectacular part is the completely intact three-story stage. As the theatre was half full of sand until about 1930, all but four of the 30 white limestone columns with Corinthian capitals on the first level behind the stage are present. It is easy to see how they provided a contrast to the black basaltic rock and improved the acoustics of the theatre. Only 4 small column remnants remain on the second story and none on the third. The stage has many niches that once held statues.

The large semi-circular orchestra pit has original stone pavers, but now with two bomb scars.

Nova Trajana Bostra Roman Town. With several intact buildings, it is one of the better Roman ruins in the world. The 1.3km Cardo Maximus bisects the city and has an almost complete Abbatean Gate. Walking along the Deccamanos (secondary street), pass the columned sports hall and huge bath with a room with possibly the only (almost) intact domed ceiling in any Roman ruin. After the theatre, the most spectacular building is the small nymphaeum with an intact stone roof and lovely niches topped with scallop shell design.

JERASH, Jordan

These beautifully preserved Roman ruins, located 51 km north of Amman, are deservedly one of Jordan’s major attractions. Excavations have been ongoing for 85 years but it is estimated that 90% of the city is still unexcavated. In its heyday the ancient city, known in Roman times as Gerasa, had a population of around 15,000.

History. Although inhabited from Neolithic times, and settled as a town during the reign of Alexander the Great (333 BC), Jerash was largely a Roman creation. Rome annexed the Nabataeon Kingdom in south Jordan in 106 BC.

In the wake of Roman general Pompey’s conquest of the region in 64 BC, Gerasa (as Jerash was then known) became part of the Roman province of Syria and, soon after, a city of the Decapolis. The city reached its peak at the beginning of the 3rd century AD when it was bestowed with the rank of Colony, after which time it went into a slow decline as trade routes shifted.

The Roman ruins at Jerash cover a huge area.

At the extreme south of the site is the striking Hadrian’s Arch built in AD 129 to honour Emperor Hadrian who spent the winter here. Behind the arch is the Hippodrome (220-749), the smallest and best preserved in the Roman Empire. It hosted chariot races watched by up to 17,000 spectators. In the 8th century, the hippodrome served as a mass burial site when the plague struck. The Church of Mariano is just across from the hippodrome; it has a wonderful quite intact mosaic floor.

The South Gate and the 3.4km long city wall were built in AD 130 after the city was looted and burned. The terrace below the Temple of Zeus shows the complete succession from the early Bronze Age to late Roman times – successive churches dating from 27 AD, 70, 162 and a 5th-century Byzantine church are represented archaeologically. The Oval Plaza is unusual because of its shape and huge size (90m long and 80m at its widest point). Sixty-two Ionic columns surround the paved limestone plaza, linking the cardo with the Temple of Zeus.

The elegant remains of the Temple of Zeus supported by 38 columns were built around AD 162. It is a worthwhile climb if just for the view. Next door, the South Theatre was the most elegant and largest of the three theatres in Jarash. Built in 96 AD with 30 rows and a capacity of 5000 spectators, the acoustics are still wonderful as demonstrated by the two Arabs playing the drums and bagpipes.

Between the Oval Plaza and the North Gate is the 800m-long Cardo, the city’s main thoroughfare. It still has 253 columns flanking it. It is paved with the original stones laid diagonally for easier driving by the thousands of chariots that once jostled along its length. Along the street is the Nymphaeum (190-749), the main fountain of the city and the Propylaeum or grand approach, with a 30m wide staircase leading to the Temple of Artemis (135-749). Bisecting the cardo are the North and South Decumanui, two east-west streets, both lined with more columns and with their original paving stones intact (manhole covers still have some of their original metal rings for exposing the sewer that ran under all the streets). At the intersections with the cardo are the North Tetrapylon (a massive domed arch) and the South Tetrapylon (only the bases of the original pink granite columns imported from Aswan in Egypt remain).

Walking up the North Tetrapylon leads to the North Theatre (165-749), a gorgeous 21-row theatre restored to its former glory.

Next is the Temple of Artemis – Artemis was the patron goddess of the city – but the temple was never finished and subsequently dismantled to provide masonry for new churches. Twelve great columns remain.

23 Byzantine Churches were built in Jarash and several have been excavated many with great mosaic floors: the Cathedral (450-749), Church of Propylaea (565-749), Church of Bishop Isaiah (558-749), the triple Churches of St George, St Cosmos and Damiaes (twin brothers, both physicians martyred for providing free of charge medical care) and Church of St John the Baptist (largely intact mosaics), Church of Saints Peter and Paul and the Mortuary Church.

The small museum contains a good collection of artifacts from the site.

GADERA, Umm Qais Jordan

Tucked in the far northwest corner of Jordan, and about 25km from Irbid, are the ruins of Umm Qais, the site of both the ancient Roman city of Gadara and an Ottoman-era village. The hilltop site offers spectacular views over the Golan Heights in Syria, and into Israel, the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias) to the north, and the Jordan Valley to the south. The terrain here is mountainous with deep valleys and rocky terrain with sparse olive and pine trees.

Roman Ruins Entering the site from the south, the first structure of interest is the well-restored and brooding West Theatre. Constructed from black basalt, it once seated about 3000 people. This is one of two such theatres – the North Theatre is overgrown and missing the original black basalt rocks, which were recycled by villagers in other constructions. Nearby is a colonnaded courtyard and the remains of a 6th-century Byzantine church.

Beyond this is the decumanus maximus, Gadara’s main road running 1.5 km on an east-west axis. 6.5m wide, it is all basaltic rectangles set on diagonals, heavily rutted from chariot wheels. The road was colonnaded but only about 13 complete columns remain. The rest are lying all over the place. A set of overgrown baths are to the west. Further along is a basilica (360 AD) built atop a Roman mausoleum. This is the location of the “miracle of Gadara” described in the New Testament in Matthew 8:28: “On his way from Lake Genezareth in Gadarone country, Jesus met two possessed men who dwelled in the tombs on the outskirts of the city. Jesus healed them of their affliction by driving out their devils into a herd of swine, which thereupon plunged into the water.”

SEBASTIA, Nablos, Palestine

2kms NW of Nablus is this village with ruins on the top of the hill (acropolis). There is evidence of the occupation of the hill since the early Bronze Age (3200BC), Iron Age, Assyrians (722BC), Persians (538-332BC), and Alexander the Great (circular tower). The Romans were here from 63BC to 324AD when the city was part of the province of Syria. Emperor Octavian (who was renamed Augustus in 27 BC) gave it to King Herod in 30 BC to govern in the name of Rome and Herod renamed it Sebastos (or Augustus meaning ‘great’ or ‘revered’). The Romans constructed the city wall, a colonnaded street with 600 columns, the basilica, forum, theatre, temples of Augustus and Kore, the stadium and aqueduct. The Byzantines (324-636AD) built 2 churches dedicated to John the Baptist, the Muslims a mosque and the Crusaders a cathedral.

PERGE Turkey Tentative WHS (06/02/2009)

PERGE Turkey Tentative WHS (06/02/2009)Perge, one of the Pamphylian cities was believed to have been built in the 12th to 13th centuries BC. After coming under the rule of Lydia and Persia, the city surrendered to Alexander the Great in 334 BC. The brightest era of the city was during the reign of the Romans in the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD.

Ancient Perge is famous as Saint Paul visited Perge in 46 AD and preached his first sermon. That is why it became an important city for the Christians during the Byzantine period.

All the remains of the city can be seen in this area. Social and cultural buildings reflecting the majesty of the Perge Ancient City are the necropolis, theatre, city walls, stadium, gymnasium, Roman baths, rectangular planned agora, high towers, monumental fountains, column-lined streets, and Greek and Roman gates.

Basilica and Baths: The first entrance to the city is the Roman gate of the later period. On the right, there is a Byzantine basilica. After the basilica comes the agora and on the left there are baths. Among the cities of Pamphylia, the largest and most glamorous baths were to be found in Perge.

City Walls: Two walls that run parallel to each other have become the symbol of Perge and are dated to the 3rd century BC. The oldest gate of the city is in these walls as well as two towers, all from the Hellenistic period. After the Hellenistic gate comes a colonnaded street.

Theatre and Stadium: The theatre is away from the historical site and is the first view of the city you have on the road when approaching the entrance. Behind the theatre is the impressive and large stadium, the principal structure of the ancient city of Perge. It is one of the best-preserved stadiums of the ancient world and the second largest after the stadium in the ancient city of Aphrodisias.

ZEUGMA Turkey

A tentative WHS (13/04/2012), Zeugma is 10 km from Nizip and 50 km west of Gaziantep. Zeugma, literally “bridge” or “crossing” in ancient Greek, was located at the major ancient crossing on the river Euphrates. Zeugma was a twin city on the opposing banks of the river, but today the name Zeugma is usually understood to refer to the settlement on the west bank.

They were Hellenistic settlements established by commander Seleucus Nicator around 300 BCE. The twin settlements were crucial in the cultural policies of the Seleucid Empire integrating Greco-Macedon and Semitic cultures in the region. In 64 CE, Seleucia came under the rule of the Commagene Kingdom, and then from 72 CE, it was the major eastern frontier city of the Roman Empire. With two Roman legions based in Zeugma in the first century CE, its strategic importance and cosmopolitan nature increased greatly. Due to its crucial position on commercial routes and the volume of traffic, Zeugma was chosen by the Romans for toll collecting. Zeugma prospered and functioned as a major commercial city and a military base.

The preserved parts of the ancient city include the Hellenistic Agora, the Roman Agora, two sanctuaries, the stadium, the theatre, two bathhouses, the Roman legionary base, administrative structures of the Roman legion, the majority of the residential quarters, Hellenistic and Roman city walls, and the East, South and West necropolis (none of this is visible today – only the Roman houses below are visitable).

Most of these remains date from the period between the first century BCE (the time of Antiochus, king of Commagene (64 BCE-72 CE) and the third century CE Roman period when the city was sacked by the Sassanian King Shapur in 253 CE. Commagene was a Roman client kingdom. Commagene is represented by two sanctuaries consecrated by Antiochus in the city showing the key role in Antiochus’ efforts to link the Greek and Persian cultures, under the kingdom’s key position between these two worlds, on the Euphrates. Belkıs Hill – the foremost sanctuary has three colossal cult statues and many others in pieces on the slopes of the hill. They are dexiosis stelai showing Antiochus in a hand-shaking position with the Gods. These statues most probably belong to the deities of the Commagenian pantheon. Both are in the Ganzintep Mosaic Museum.

Necropolis of Zeugma. Tombs and burials from the late 3rd century to the 3rd century AD range from Hellenistic rock-cut cist graves of the earliest Graeco-Macedonian settlers to the late Hellenistic and early Imperial tumuli (rock-cut rectangular slots, loculi-type graves, and rock-cut arched grave niches. The walls of the chambers were covered with frescoes and painted with flowers using bright colours such as red, green, and yellow. Most belonged to elite families in the city.

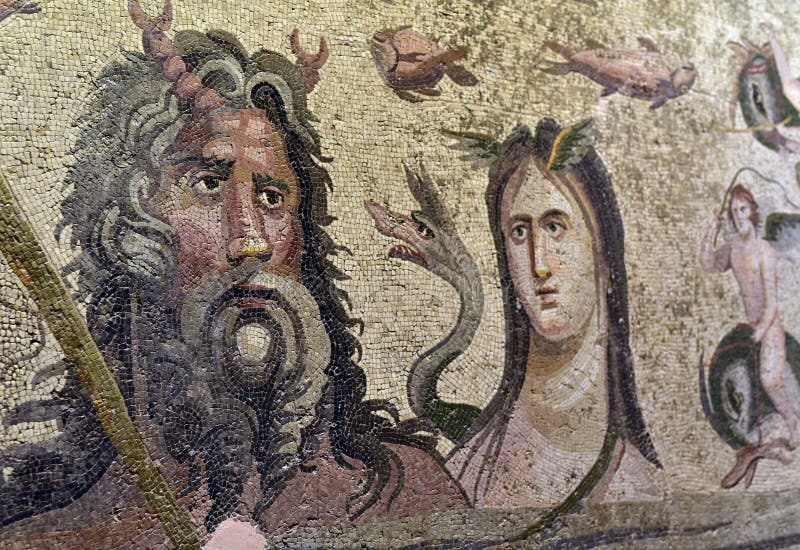

The Roman Houses of Zeugma form the main covered exhibit. They are in the style of city villas with courtyards, covering around 600-800 square meters each. What makes the houses especially important is that after being demolished during the devastating Sasanian sack of the city in 253 CE, they were mostly uninhabited and kept intact providing invaluable information on daily life in a major Roman frontier city in the mid-third century. What remains are ruins of some walls and about 8 standing columns with mosaics displayed.

The architectural decoration of the houses mainly consists of exquisite mosaics and frescoes dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. Zeugma mosaics are a unique collection of pictorial art including unique pictorial renderings of Greek and Greco-Roman mythologies and popular novels, some with captions in Greek. Some also bear the signatures of mosaicists as well as the names of patrons who commissioned the implementation of the mosaics.

The House of Dionysos depicted the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne, complete with servants bringing wedding presents and musicians. The House of Danae has a mosaic depicting the moment when Danae and Perseus were rescued by the fishermen Dictys on the shores of Seriphos Island after having drifted ashore in a nuptial chest. This house has some faded frescoes in one room. Most of the rest of the mosaics are some nice geometrics.

The Houses of Poseidon and Euphrates are lower and flooded by the dam on the Euphrates River built in 2000. Most of the mosaics and frescoes found in them were relocated to the Gaziantep Museum.

This sits on the banks of the Euphrates Reservoir about 7 km north of the highway. Park at the grossly overbuilt Visitors Center and walk 400m to the exhibit. Free

Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Gaziantep. With 66 mosaics, most from Zeugma, this is not to be missed. The Theonoe Mosaic at 71.57m2, is the largest and was rescued from the bottom of the reservoir (Birecik Dam) only when the water level dropped in 2002. Many are geometrics and Greek and Roman mythological scenes with a variety of geometric borders. A separate building houses several Byzantine 5th century mosaics including a huge one from a church. These are not as well done as the Zeugma mosaics.

.jpg)

There are also sarcophagi, frescoes from Zeugma, and all the stelae from Zeugma. TL24

There are also sarcophagi, frescoes from Zeugma, and all the stelae from Zeugma. TL24

VILLA ROMANA DEL CASALE Sicily

Built in the 3rd century BC, it is one of the few remaining sites of Roman Sicily. A sumptuous hunting lodge belonging to Diocletian’s co-emperor Marcus Aurelius Maximianus, it was buried under mud in a 12th-century flood and remained hidden for 700 years before its magnificent floor mosaics were rediscovered in the 1950s. They were only fully opened to the public in 2013 after years of restoration and are among Sicily’s greatest classical treasures.

The mosaics cover almost the entire 3500 sq. metre floor of the villa and are considered unique for their narrative style, the range of subject matter and the variety of colours. Many have African themes.

Surrounding a huge central fountain lined by marble columns are many mosaics of animals. Along the eastern end of the internal courtyard is the Great Hunt – scenes of capturing animals in Africa for gladiatorial contests in Rome – chariots, wagons with cages, boats for shipping the animals and a huge variety of critters. Around the courtyard and corridor are several apartments, the simple ones with intricate, unique geometrics. The most captivating are the Ten Girls in Bikinis with sporty girls in scanty bikinis playing sports.

The owner’s grand hall is covered in intricate marble from all over southern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. At the front are a series of baths with hot, warm and cold water, heated from underneath.

It is difficult to get here without a vehicle. They are located in the centre-eastern part of Sicily near the town of Piazza Armenia. Park below (1€/hour) and walk up to the villa (10€).

I spent 3 hours reading all the excellent descriptions describing the use of each room and the finer points of each mosaic.

SEGOVIA, Spain

A Unesco World Heritage site with its Roman aqueduct – 894 m long engineering wonder built in the 1st century with 163 arches and 28m height.

PROVINCE, France

PONT du GARD. Nothing can top this Unesco-listed Roman aqueduct. 21kms NW of Nimes, this massive three-tiered aqueduct was one of many bridges on the 50km-long system of water channels built around 19 BC to transport water from Uzès to Nimes. Built to cross the Gard River, the scale of Pont du Gard is huge: 48.8m high, 275m long, and with 52 arches remaining – 6 on the bottom of the river, 10 next, and 36 small ones supporting the water channel (there were 44 but several were demolished for the stones). It carried 20,000 cubic meters of water per day.

Each block was carved by hand and transported from nearby quarries – some weighed 5 tons. The gradient of the entire 50km system was about 12cm per kilometre and dropped only 2.5cm over the length of the bridge – an amazing demonstration of the precision of Roman engineering.

The museum gives a detailed account of every bridge in the entire system and a good description of all the building techniques.

NIMES. (pop 154,000). 2000 years ago it was one of the most important cities of Roman Gaul.

Les Arènes. This two-tiered amphitheatre is the best-preserved in France. Built around 100 BC, the areas once seated 24,000 and staged gladiatorial contests and public executions. It is still used for concerts, events, and in the summer, bullfights. At 133m by 101m and 2 stories high, and despite being plundered for stone and generally abused, it is still largely intact,

EL-JEM ROMAN COLISSEUM Tunisia

The Colosseum rises from a low plateau halfway between Sousse and Sfax, dwarfing the tiny modern town around it. Built 2000 years ago by olive oil traders with money to burn, it’s the culmination of a couple of centuries of engineering expertise. It included state-of-the-art features including a movable floor – all the better to showcase gladiatorial combat, executions of Christians and other forms of Roman popular culture.

The Coliseum of Thysdrus is a magnificent structure. It is an oval – 149X124m – and holds 30,000 spectators in 5 tiers of seating (Rome’s Coliseum held 43,000). The structure has 5 levels of great keystone arches holding up the 5 levels of walkways giving access to the seating. Walk through the hypogeum, the underground area that held the animals and gladiators raised on elevators to the area of combat. It was originally covered by a wood

ceiling.

Its beautiful archaeological museum is home to an outstanding mosaic collection, better than that in the Bardo: some wonderful geometrics and many depicting animals (including a great peacock) and gladiators.

VOLUBILIS Morocco

Amid a fertile plain about 33 km north of Meknès, Volubilis (Ouailili) are Morocco’s largest and best-preserved Roman ruins (and the breadbasket for Rome). Established in 25 BC, the Romans left in 265 AD. The Madrid earthquake of 1755 destroyed much of the ruins. Of a total of 50 acres, only about 15 have been excavated, initially by the French in 1915. 120 olive presses and 60-grain mills have been discovered.

Volubilis is best known for its mosaics which are in remarkable condition despite being exposed to the air for 2,000 years. The huge patrician’s houses have entry courtyards with a pool – one in an unusual scalloped pattern for sunbathing in different directions. The “column house” has fluted and very unusual spiral columns with Corinthian, Doric and Ionic pilasters.

FRONTIER of the ROMAN EMPIRE – Hadrian’s Wall

Julius Caesar first attempted to invade the British Isles in 54-55 BC but was unsuccessful. They tried a second time in about 50 AD and were able to subjugate the island. Eventually, they controlled the entire island extending even to the islands north of Scotland under Trajan (68-117 AD).

Trajan’s adopted son Hadrian was the only emperor with a beard, he didn’t spend much time with his wife but preferred Antinous, a young man renowned for his beauty; he is known for building the Parthenon in Rome He visited the north of England in 122 and was emperor from 117-138 AD and consolidated power to an area running diagonally across the north of England. He built Hadrian’s Wall between 120-128 to keep out the Picts. The defences across the north consisted of 6 forts along the west Solway coast (including Alauna at Maryport) and the wall extended 73.5 miles (80 Roman miles) from Bowness on the Solway Firth in the west to the mouth of the Tyne at Wallsend on the east coast. Three legions (about 16,000 men) were in Britain and all took part at various times in the construction and patrolling of the wall.

Much of the western part of the wall was made from dirt, sod, and timber of which nothing presently exists, but most of the wall was substantial rock, 2 meters wide filled with rubble and dressed with stone on both sides. An elevated walkway was protected by a crenellated wall. Seventeen major forts were constructed along the wall; 80-mile castles were every Roman mile (.95 mile) and turrets were about every ⅓ mile. There was also a ditch and four bridges where rivers were crossed. The forts were in large rectangular enclosures with four gates.

Rome controlled Britain for 300 years but withdrew in about 400 AD when the Roman Empire started to fail. The entire area was Unesco listed in 1987 as Frontiers of the Roman Empire.

Over the centuries, most of the stone from the wall was removed and used to build local projects.

Hadrian’s Wall Path (www.nationaltrail.co.uk/hadrians-wall-path) is an 84-mile national trail that runs from Wallsend to Bowness

Marysport Roman Museum. Settled by the Romans in the 2nd century, this was the most northerly extension of the Roman Empire. Named Alauna, the fort on the cliffs covered 6.5 acres and was garrisoned by up to 1000 soldiers from Austria, Italy, Provence France, Croatia, and North Africa, They were posted here for 3-4 years and occupied the area for 280 years. It was the military outpost on the Solway Coast’s west end to Hadrian’s Wall’s west end. The Roman Museum has 5 altars and remains of a temple.

Birdoswald Roman Fort. This has the longest intact stretch of wall and the remains of a large fort. The east edge of the property drops vertically down to the River Irthing.

Roman Army Museum. On the site of the Carvoran Roman Fort, this excellent museum gives the most information about the construction of the wall and the soldiers who manned it with several 3D presentations. 6.7£

Housesteads Roman Fort. This is the best-preserved Roman fort. High on a ridge and covering 2 hectares, it has good views of Northumberland National Park and the snaking wall. It had a hospital, granaries, barrack blocks, and flushable toilets.

Chesters Roman Fort. Near the village of Chollerford, it includes part of a Roman bridge, four gatehouses, a bathhouse, and underfloor heating.

ROMAN ROADS 200,000 miles of Roman roads provided the framework for the empire.

Built during the republic and empire, a vast network of roads made moving goods and troops easier through all corners of the Roman world.

Ancient Rome was famous for many things, many of them big and flashy. Gladiators, triumphs, and emperors often spring to mind, but perhaps Rome’s most enduring contribution to history is more humble: their roads (which all led back to Rome), a vast, interconnected network spanning as many as 200,000 miles at its maximum.

Across Europe, parts of North Africa, and the Middle East, the remnants of these roads can be found crisscrossing the landscape, from Scotland to Mesopotamia, from Romania to the Sahara. Rome’s earliest roads were built to connect the city on the Tiber with other cities on the Italian Peninsula. As Rome’s influence grew, their system of roads expanded too. They became arteries connecting new territories and their peoples to Roman civilization and eventually the Roman Empire. Some 30 roads from all points of Italy connected with Rome, many bearing the names of their builders, such as the Appian Way named for Appius Claudius, or the names of their destinations, such as the Ardeatina Way that led to Ardea, about 24 miles from Rome.

Roads were Rome’s “DNA” from the very beginning. Begun in 451 B.C. and finished a year later, the Lex XII Tabularum, or Law of the Twelve Tables, was the earliest set of written policies. Inscribed on 12 bronze tables, they spelled out procedures for trials, property ownership, crime and punishment, and civil rights. They also included rules for the road, setting a standard width of eight Roman feet for straight roads and 16 for curved ones (one Roman foot is slightly longer than a foot in the modern Imperial system).

The Appian Way

The Via Appia, or Appian Way, is perhaps the most famous Roman road. Paved with large basalt slabs, it was built in the fourth century B.C. at the direction of Censor Appius Claudius. At first, the road connected Rome to Capua, about 132 miles away in the Campania region of Italy. By 244 B.C. the road had been extended south more than 200 miles to reach the port city of Brundisium (modern Brindisi) on the Adriatic coast of southern Italy. (See a fourth-century map where all roads really do lead to Rome.)

Because the road became the main conduit from Rome to the Adriatic ports and the Mediterranean, the Appian Way became a crucial component of Rome’s economy as well as its military. It was wide enough for two carts to pass in opposite directions or for five soldiers to march side by side. Building the Appian Way was a massive undertaking, but the excellent craftsmanship of the road was apparent for centuries. First-century A.D. Roman poet Statius called it longarum regina viarum (queen of the long roads). Writing hundreds of years after its construction, the sixth-century A.D. Byzantine historian Procopius also lauded its engineering:

It . . . is one of the most remarkable achievements because the stone, by nature very hard, did not exist in this part of the country and had to be transported from afar. The stones were smoothed and levelled, then cut into angular shapes and fitted one next to the other without the need to join them with bronze or any other thing. So they are so well nested and assembled that they have the appearance of a single compact mass . . . Despite the long period of time that has elapsed, and the continuous passage of so many carriages and beasts of burden, no stone has been displaced from its original position, nor has any been worn or lost its polish.

Ancient scholars of the Roman Republic have left detailed accounts of how roads were built— from contracts to construction. Roman historian Livy described how second-century B.C. censors Quintus Fulvius Flaccus and Lucius Postumius Albinus “were the first to award contracts to pave roads in the city with stone, with gravel on the sides, and to build curbs as well as bridges in many places.”

First-century A.D. Greek biographer Plutarch’s biography of Gaius Gracchus, one of the Roman Republic’s most significant politicians, offers rich insights into roadbuilding. A plebeian tribune in the second century B.C., Gracchus made road-building his main focus, joining utility and beauty in roads that traversed the land in a straight line, without turns or detours, and foundations made of cut stone, reinforced with layers of sand or compacted gravel. The depressions were filled and bridges were built over the rivers and streams, the two sides at the same height and always parallel, so that the entire work had a uniform and beautiful appearance. In addition, he measured the entire road and at the end of each mile, or roughly 5,000 feet, he put a stone column that served as a signal to the travellers.

Road maps

Historians of Roman roads rely on “itineraries,” Roman documents that catalog the layout of the Roman roads, with the names of towns, lodgings,and distances between them. The main one is the Antonine Itinerary, perhaps from the time of Diocletian (r. A.D. 284-305), which includes a “road map” of Roman Britain. Another key source is the Peutinger Table (above), a medieval copy of a Roman road map in 12 sections, one of which is missing.

Building the roads

When planning to build a road, engineers studied the local topography and gathered information from residents. They then plotted out the most logical course, prioritizing straightness and moderate slopes. When crossing flat land, the road was as straight as possible: the ancient Appian Way, between Rome and Terracina, includes an uninterrupted straight line 56 miles long.

In hilly terrain attempts were made to even out the elevation through cuttings, bridges, and viaducts. In mountainous areas the engineers made wide curves, adapting to the land to maintain uniform slopes. In high mountains they used tight turns and even tunnels. Whenever possible, the road was laid out on the eastern and southern slopes to take advantage of the greater amount of sunlight to prevent winter snowfalls from impeding travel. (These 10 ancient highways wrap around the world.)

After a public bidding process, private contractors would be awarded the project to build a road. They hired labourers but also relied on enslaved people and criminals sentenced to forced labour. Sometimes they used the army and military engineers to design or direct the work. Legions also built roads as part of military operations and in conquered areas. Sometimes, when a legion was inactive, the commanders, or legates, decided to put the soldiers to work on road construction, as did the consul Gaius Flaminius, for example, whose men built the Flaminian Way from Rome over the Apennine Mountains to Ariminum (Rimini) in 220 B.C.

Ideally, the materials for road construction came from nearby quarries; if not, they might have had to be imported. The work began by clearing the ground of trees, rocks, and everything that could be an obstacle. The soil was drained, and rainwater runoff was diverted through channels and sewers. Then a ditch was dug and filled with large, loosely placed stones that allowed drainage. Medium-size boulders were added to compact the layer below and fill in large gaps, on top of which a layer of sand and gravel was spread to provide a more comfortable surface for carts. These layers, which elevated the road above the surrounding terrain, were then compacted and hardened with water, hand tampers, and a large stone roller. The road was then flanked with curb stones. To the sides of the curbs large ditches were dug to receive the runoff from rain, a road’s greatest enemy. (Discover the secrets of London’s oldest Roman road.)

To complete the work, cylindrical stone posts were placed at intervals of one Roman mile (measured by a thousand steps, or the milia passum). These milestones, which could stand over eight feet high, marked the distances and gave credit to the person who sponsored the road’s construction.

Today it can sometimes be difficult to identify an ancient road as Roman; because their building techniques were so successful, that they were adopted again in the 18th century. In Roman times soldiers, farmers, and traders often wore shoes called caligae, which had studs on the bottom to protect their leather soles. Often these studs would fall off and get stuck in the road, leaving behind a valuable clue for future archaeologists to help prove a site’s Roman origins.

Resting easy

Roman roads not only allowed for easier transport of soldiers, supplies, and trade, but also supported the growth of new communities and services. Many Roman roads were topped with a final layer of gravel; when passed over by a continuous stream of soldiers and carts, the roads grew dusty. Second-century A.D. Roman historian Suetonius alludes to this in his biography of Emperor Caligula:

He started the march and did it with such precipitation that the Praetorian cohorts, by necessity and against custom, had to affix their badges on their baggage to be able to follow each other. As he travelled in a litter carried by eight men, the troops followed so slowly that he demanded that the inhabitants of neighbouring cities sweep the road and water it to cut back on the dust.

To help travelers stay fresh, they could stop at a mansio, an official service establishment that sprang up along Roman roads. Hostels and relay stations were located at a distance equivalent to one day’s worth of travel, typically about 20 to 25 Roman miles. These facilities, grouped around a central courtyard, had stables and troughs for the horses, a place to eat, and sleeping quarters. Some offered public baths so travelers could wash off the dust. (A complex network of aqueducts quenched Rome’s thirst.)

As the Roman Republic and then the empire expanded, so too did its network of roads. The roads built during the republic enjoyed a renaissance under Augustus who reinvigorated the system for building and maintaining the roads. Augustus understood the vital importance of these arteries, not only for moving armies and commerce along their paved paths, but also as a symbol: A network, created out of dazzling technical know-how, that united the growing empire, and brought its subjects the benefits of Roman rule. New roads were built in newly conquered lands in Britain and in Syria. Today many Roman roads have become the foundation for the major highways and byways in the former Roman world, a testament to the skill of the engineers who designed and built them.