A 6-hour bus ride south through hilly terrain covered in thorn trees and cacti (a cross between saguaro and organ pipe) brought me to Tupiza (pop 23,000, elevation 3200 m) in the southwest corner of Bolivia. It is about 40 km south of Huaca Hualusca. Tupiza has a spectacular landscape reminiscent of the red rock area around Sedona, Arizona. There were extremely eroded columns, fins, arches, and hoodoos in the 2 canyons.

The 4-day/3 night tour from Tupiza to Uyuni was a 1200 km 4WD drive through the altiplano of SW Bolivia, all on dirt and gravel roads. There were 13 customers in 3 Toyota Land Cruisers.

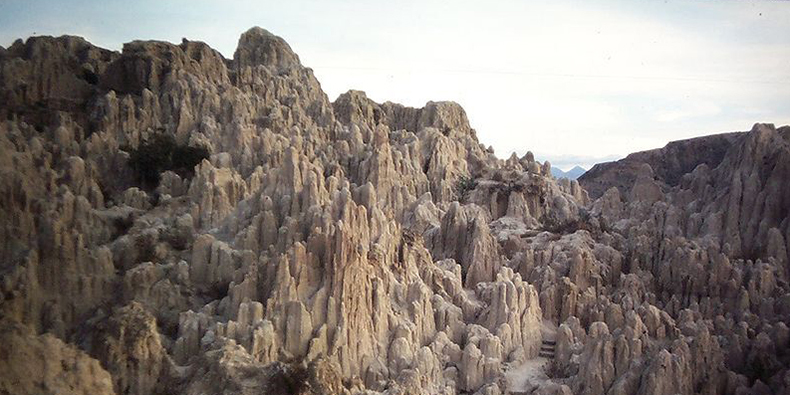

Valley of the Moon was formed due to erosion consuming the upper part of a mountain, made up of clay soil. Over the centuries, the modelling from wind and rain has built this spectacular and unusual landscape of white chimneys. The colours depend on the type of mineral content found in each mountain – most are brown / beige but a dark reddish colour). Two circular trails lead you to different viewpoints. Devil’s Point takes about 45 minutes. The other track takes 15 minutes.

The road was very dodgy with washouts, huge mud holes, and no bridges over the many streams and river crossings. It was much more about the road than the scenery initially as we passed through high treeless Altiplano, low hills, and snow-covered mountains in the distance. We got stuck twice requiring short tows. It was below freezing at night. There were many herds of llamas (all domesticated and raised for their meat) and many vicuñas (all wild).

Day 2. On the second day, we crossed a pass at 4855m and reached the tri-point where the borders of Argentina, Chili, and Bolivia meet at a high green lake (coloured by arsenic and magnesium) under a big volcano.

The Altiplano of Bolivia is a high plateau formed during the uplift of the Andes mountains. The plateau includes fresh and saltwater lakes and salt flats surrounded by mountains with no drainage outlets.

We turned north passing through a high desert with no plants. The altitude was between 4600 and 5000 m with altitude sickness a possibility. The views were of big skies and scattered snow-covered mountains. We passed through the Dali Desert (a bleak white slope with small rock outcrops), and a geyser field with several active fumaroles, and unusual eroded sandstone formations.

Pass several high lakes, some with thousands of pink Andean flamingos. The lakes are dry in the dry season when all the flamingos migrate to Chili.

Day 3. We had a nice soak in a hot spring at 5000 m on the edge of a lake before Uyuni (pop 20,000), one of the butt-assed ugliest towns in the world.

Uyuni Salt Flats. The biggest attraction in Bolivia, at 12,108 square km, is the largest salt flat or playa in the world. It is in southwest Bolivia, near the crest of the Andes at an elevation of 3,656 m (11,995 ft) above sea level. With 11 layers of salt and water, it is 2-20 m thick and contains the most energetic minerals in the world – lithium, magnesium, sulphur, potassium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and borax. Bolivia owns 50% and Chili 40% of the world’s lithium, all contained in these large salt flats.

The Salar formed between several prehistoric lakes that existed forty thousand years ago but had evaporated over time. It was now covered by a few meters of salt crust that was extraordinarily flat. The average elevation variation was within one meter over the entire Salar area. The crust serves as a source of salt and covers a pool of brine, which is exceptionally rich in lithium.

The large area, clear skies, and exceptional flatness of the surface make the Salar ideal for calibrating the altimeters of Earth observation satellites. Following rain, a thin layer of dead calm water transforms the flat into the world’s largest mirror, 129 km across.

The Salar serves as the major transport route across the Bolivian Altiplano and is a prime breeding ground for several species of flamingos. Salar de Uyuni is also a climatological transitional zone. The tropical clouds that form in the eastern salt flat don’t reach the drier western edges, near the Chilean border and the Atacama Desert.

Salar de Uyuni as viewed from space, with Salar de Coipasa in the top left corner

Lacustrine mud interbedded with salt and saturated with brine underlies the surface of Salar de Uyuni. The brine is a saturated solution of sodium chloride, lithium chloride, and magnesium chloride in water. It is covered with a solid salt crust varying in thickness between tens of centimetres and a few meters. The center of the Salar contains a few islands, which are the remains of the tops of ancient volcanoes submerged during the era of Lake Minchin.

Bolivia holds about 22% of the world’s known lithium resources (105 mln. tons); most of those are in the Salar de Uyuni.

Lithium is concentrated in the brine under the salt crust at a high concentration of about 0.3%. It is also present in the top layers of the porous halite body lying under the brine; however, the liquid brine is easier to extract, by boring into the crust and pumping out the brine. The brine distribution has been monitored by the Landsat satellite and confirmed in ground drilling tests. Following those findings, an American-based international corporation has invested $137 million to develop lithium extraction.

However, lithium extraction in the 1980s and 1990s by foreign companies met strong opposition from the local community. Locals believed that the money infused by mining would not reach them. The lithium in the salt flats contains more impurities, and the wet climate and high altitude make it harder to process.

No mining plant is currently at the site. Salar de Uyuni is estimated to contain 10 billion tonnes of salt, of which less than 25,000 t is extracted annually.

The Salar is virtually devoid of any wildlife or vegetation. Giant cacti grow about 1 cm/a to about 12 m. Every November, Salar de Uyuni is the breeding ground for three South American species of flamingo feeding on local brine shrimps: the Chilean, Andean, and rare James’s flamingos.

Antique Train Cemetery. It is 3 km outside Uyuni and is connected to it by the old train tracks. The town served as the train hub carrying minerals to Pacific Ocean ports. The rail lines were built by the British at the end of the 19th century for use by mining companies. In the 1940s, the mining industry collapsed, partly because of mineral depletion. Many trains were abandoned, producing the train cemetery.

Salt flats are ideal for calibrating the distance measurement equipment of satellites because they are large, stable surfaces with strong reflection, similar to ice sheets. As the largest salt flat on Earth, Salar de Uyuni is especially suitable for this purpose. In the low-rain period from April to November, due to the absence of industry and its high elevation, the skies above Salar de Uyuni are clear, and the air is dry (relative humidity is about 30%; rainfall is roughly 1 millimetre or 0.039 inches per month). It has a stable surface, smoothed by seasonal flooding — water dissolves the salt surface and thus keeps it level.

As a result, the variation in the surface elevation over the 10,582-square-kilometer area of Salar de Uyuni is less than 1 meter (3 ft 3 in) normal to the Earth’s circumference. Few areas on Earth are as flat. The surface reflectivity (albedo) for ultraviolet light is relatively high at 0.69 with variations of only a few percent during the daytime. The combination makes Salar de Uyuni about five times better for satellite calibration than the surface of an ocean. Using Salar de Uyuni as the target, ICESat has achieved a short-term elevation measurement accuracy of below 2 centimetres.

Salar de Uyuni is a popular tourist destination. Hotels have been built. Due to a lack of conventional construction materials, they are almost entirely (walls, roof, furniture) built with salt blocks cut from the Salar. The first such hotel, Palacio de Sal, was erected in 1993–1995 in the middle of the salt flat and soon became a popular tourist destination. However, waste had to be collected manually. Mismanagement caused serious environmental pollution and the hotel had to be dismantled in 2002.

Around 2007, a new hotel, Palacio de Sal, was built on the eastern edge of the Salar, 25 km from Uyun. The sanitary system has been restructured to comply with the government regulations. The hotel has a dry sauna, a steam room, a saltwater pool and whirlpool baths.

The water presents a perfect mirror with a limitless horizon punctuated by many intermittent snow-capped mountains ringing the flats. They seemed to rise directly out of the water despite often being far from the lake. Tourists spend hours playing photographic games using wide-angle perspectives.

Day 4. We were driving at 5 am to see the sunrise. It was a slow drive (to avoid splashing water up into the truck’s electronics) across the flat covered with a few centimetres of water to the Salt Hotel.

The water presents a perfect mirror with a limitless horizon punctuated by many intermittent snow-capped mountains ringing the flats. They seemed to rise directly out of the water despite often being far from the lake. It was beautiful and many say this is one of the highlights of South America.

The group spent 3 hours playing photographic games using wide-angle perspectives. The composition of the photo needs to be spot-on. An easy way to get a great perspective photo at the salt flats is to bring small inanimate objects, and toy dinosaurs. a Pringles can, utensils/bowls,

The photographer needs to be close to the first subject and low to the ground. Lying down creates the optimal level that sets the shot.