This incredibly rare burial ground reveals new secrets about the Sahara’s lush, green past

A dinosaur hunter stumbled upon Africa’s largest Stone Age burial ground. More than two decades later, he can’t stop going back.

Skulls unearthed at Gobero, a remote site in Niger, date back to when the Sahara was green.

Photograph by Rebecca Hale

By Peter Gwin

Standing atop a small dune deep in the Sahara Desert, a team of scientists stared at a freshly opened grave. Three human skeletons lay on their sides, as though they’d drifted off to sleep in the loose brown sand and never awakened.

It was just before dusk during the last days of an expedition to a place called Gobero, located in Niger’s Ténéré desert. Often described as a desert within a desert, the Ténéré is almost completely devoid of rain and defined by monumental seas of shifting sand known as ergs. Here the temperature regularly exceeds 120°F, blinding sandstorms can blow in without warning, and Nigerien authorities require a platoon of soldiers to accompany visitors to guard against bandits. But this barren landscape also holds one of the world’s rarest archaeological sites, a graveyard dating back almost 10,000 years.

That morning a college student named Hannah Moots, using a small wooden pick and brush, had begun excavating a skull, its crown barely peeking out of the ground. Working carefully, she’d exposed the eye sockets and jaw and continued down the neck to find the shoulder, then followed the arm to a cluster of finger bones. But there she stopped: There were too many finger bones for just one body. Paul Sereno, the expedition’s leader, joined Moots, and soon they’d uncovered more bones—many more.

Oumarou Idé, a Nigerien archaeologist working nearby, came over to see the progress. Throughout the afternoon, other members of the team, their skin sunburned and clothes grimed with salt stains, gravitated to the dune. Even some of the soldiers, cradling their rifles, came over to see what was going on. Finally, as the light softened and the desert air cooled, a startling picture came fully into view.

The pelvis of one skeleton indicated it was a woman. Facing her were two children. Their teeth gave their ages to be about five and seven years old. The five-year-old was clinging to the older child, holding on with a tiny arm draped across the seven-year-old’s neck. The woman’s right arm curled under the older child’s head. Her left arm reached out and connected with the left hand of the five-year-old in the jumbled mass of finger bones.

The scene raised many questions: Was this a mother and her children? Who buried them in this tender embrace? And how did they die? To have been arranged so precisely, the three would have had to perish at nearly the same time and been posed in these positions before rigor mortis set in. Was it a sudden tragedy or some sort of ritual sacrifice? No cause of death was apparent—their teeth and bones signalled good health and betrayed no signs of trauma. But without soft tissue to examine, it was impossible to say how three seemingly healthy people died simultaneously.

“Maybe,” Sereno said, “they drowned.”

I was among those gathered on that dune in 2006, on assignment for National Geographic. Nearly two decades later, now with two children of my own, I’m still enthralled by the mystery of that scene. But it’s just one of many mysteries that have emerged from that place since then. Just as the Ténéré is a desert within a desert, Gobero is a scientific enigma within an enigma, one that has obsessed Sereno, Idé, and many others who continue to glean clues, teasing out a rich picture of a lost world.

So when Sereno called in 2022, soon after the pandemic lockdown had lifted, and offered me the chance to go back to Gobero, I said yes.

The idea of three people drowning in the Sahara seems ludicrous until you consider that the Sahara hasn’t always been a desert. In fact, it transforms from desert to lush savanna about every 21,000 years. A quirk in Earth’s planetary mechanics periodically causes its axis to tilt slightly, increasing the amount of radiation directed to the Northern Hemisphere, which in turn pulls Africa’s seasonal rains northward. For millions of years, this cycle of monsoon shifts has created numerous wet periods in the Sahara. The most recent one began at the end of the last ice age, roughly 12,000 years ago, and persisted until about 4,500 years ago.

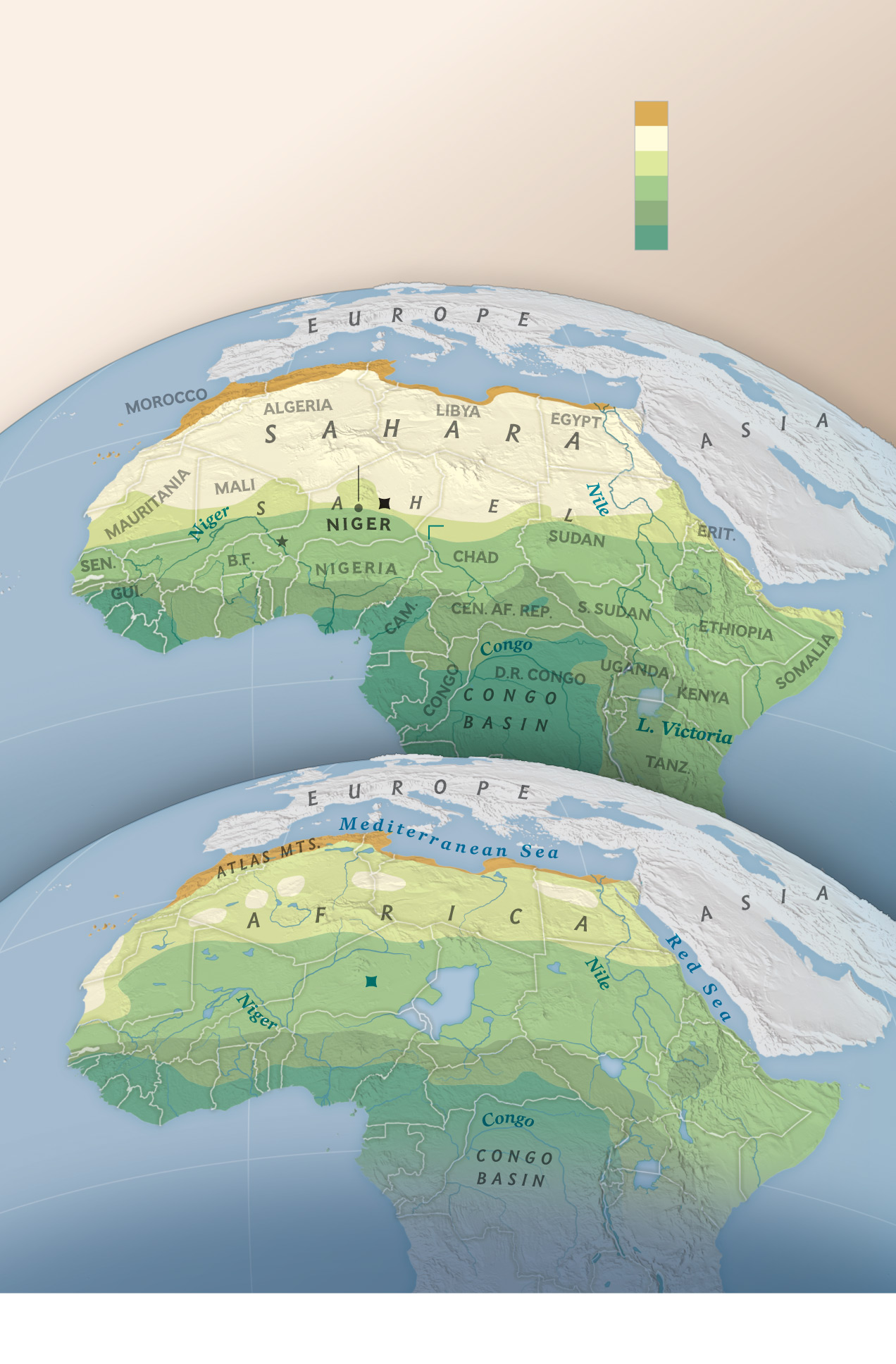

AFRICAN HUMID PERIOD circa 11,000–4,500 years ago

AFRICAN HUMID PERIOD circa 11,000–4,500 years ago

When the Sahara was Green – Biomes of Africa

Thousands of years ago, the Sahara was humid and lush—and someday could be again. Thanks to gravity, Earth’s axis wobbles, periodically increasing a region’s exposure to the sun for thousands of years at a time. More heat leads to more evaporation from the ocean, intensifying monsoons that make grasses flourish.

Technology has helped scholars see what this Green Sahara looked like. Satellites have identified ancient riverbeds and the shorelines of lakes, including the original perimeter of Lake Chad, which at its peak was bigger than all the North American Great Lakes combined.

But even more obvious clues about the Green Sahara have been staring scholars in the face. Thousands of engravings and paintings discovered on rock formations throughout the Sahara document thriving hunter-gatherer communities. The artists portrayed figures wearing elaborate headdresses and throwing spears and shooting arrows. But their main subjects were the animals they saw, including hippos, giraffes, elephants, rhinos, and antelope—species now more closely associated with wetter parts of Africa.

Despite such vivid depictions, we know very little about these people. During the 20th century, a handful of significant archaeological sites were found in the Sahara. Excavations yielded samplings of pottery and stone tools—isolated glimpses of Green Sahara cultures. But for the most part, the desert’s intense radiation, high winds, and shifting sands have scattered, buried, and scoured away much of the evidence of their existence.

So it was practically a miracle when Paul Sereno stumbled upon Gobero. He’s an unlikely scientist to find a human burial ground, as his primary subjects lived millions of years before humans. Since the early 1990s, the University of Chicago paleontologist and National Geographic Explorer has made headlines for his discoveries of new dinosaur species in the Sahara, including Afrovenator, a fast-running meat-eater; Suchomimus, a creature the length of a school bus, with a crocodile-like head; and Jobaria, a 70-foot-long plant-eater with an elongated neck.

In 2000, Sereno was looking for more of their kind as he led a scouting expedition in the Ténéré. The team spent one morning driving in a convoy of Land Rovers near a rocky ridgeline. Periodically, they’d stop to search on foot for fossils. Just as the convoy was about to return to camp, Mike Hettwer, the expedition’s photographer, wandered toward three small dunes. He found them covered with human bones, potsherds, beads, arrowheads, and other stone artifacts. “It was all there just lying on the sand,” he told me, “everywhere you looked.”

BRACELET GIRL Excavated during a 2005 expedition, a 10-year-old girl laid to rest around 4,900 years ago appears to be the most recent burial at Gobero. On her arm she wears a bracelet made from a hippo tusk. “It’s rare to find children in Neolithic burial. says expedition leader Paul Sereno. Also unusual, she was buried just a few yards from a man interred almost 5,000 years earlier. “That’s about the length of time from the first Egyptian pharaoh to my grandfather,”

BRACELET GIRL Excavated during a 2005 expedition, a 10-year-old girl laid to rest around 4,900 years ago appears to be the most recent burial at Gobero. On her arm she wears a bracelet made from a hippo tusk. “It’s rare to find children in Neolithic burial. says expedition leader Paul Sereno. Also unusual, she was buried just a few yards from a man interred almost 5,000 years earlier. “That’s about the length of time from the first Egyptian pharaoh to my grandfather,” A necklace found elsewhere at Gobero includes one stone bead and nine beads and a pendant made from hippo ivory.

A necklace found elsewhere at Gobero includes one stone bead and nine beads and a pendant made from hippo ivory.Bido Dindine, one of the expedition’s Tuareg guides, said local camel herders referred to the area as Gobero.

There were also lots of animal bones. Paleontologists study modern species to understand dinosaur physiology, and Sereno has a near-encyclopedic memory for animal skeletons. He quickly recognized the bones of hippos, giraffes, fish, crocodiles, and turtles. “All the animals we find in the Serengeti were there,” he said.

Eventually, Sereno came to understand that the three dunes were protected by a doughnut-like rim of rhizoconcretions, a type of rock formed around the roots of reeds and other plants. This created a protective crust that kept the dunes intact. When the rhizoconcretions finally started to break apart, the skeletons had begun to emerge. There were half-buried skulls, hands reaching out of the sand, ribs scattered.

“The rhizoconcretions are why those burials survived thousands of years,” Sereno said, noting the seasonal Harmattan winds, which carry Saharan dust across West Africa to the Atlantic. “Any exposed bones won’t last long.”

He showed me a photo of a skull from the 2000 trip and another photo of it in the same spot five years later. Much of the bone had been ground away—literally sandblasted. “That’s what the desert does,” Sereno said.

(Journeying along an ancient trading route in the Moroccan Sahara.)

Agadez, the closest city to Gobero, arose thousands of years after the grasslands disappeared and the Sahara became a desert. By the 1400s, it was a hub for camel caravans trading between Central Africa and the Mediterranean.

Agadez, the closest city to Gobero, arose thousands of years after the grasslands disappeared and the Sahara became a desert. By the 1400s, it was a hub for camel caravans trading between Central Africa and the Mediterranean.Mounting an archaeological dig in Niger is complicated. The country is larger than France, Germany, and Italy combined, and most of it is barren stretches of desert with little or no road access. Since gaining independence from France in 1960, Niger has endured a series of military coups and ethnic conflicts, has struggled to diversify its agriculture-based economy, and suffers from chronic food and medicine shortages. As a result, requests by foreign scientists to explore its remote eastern deserts—which border Libya and Chad, nations wrestling with their own internal conflicts—must wind their way through a lengthy government approval process.

“It’s difficult for many people in Niger to realize the value of the dinosaur fossils and the artifacts we have,” Sidi Amar Taoua, a tour guide from the desert city of Agadez, told me. “Most people are worried about access to clean water, schools for their children, job opportunities, and security.”

In the north, the country’s colonial past and the large uranium mines run by French companies have colored some Nigeriens’ views about outsiders coming to dig in their deserts. “Some people think we’re looking for oil or gold,” Dindine told me. Further suspicions were raised when the U.S. military built a large drone base in Agadez to run surveillance missions across the region.

After the initial discovery of Gobero, Sereno was able to organize four full expeditions to the site and carve out time from five other dinosaur excavations to revisit it. Some years he wasn’t able to travel because of security issues—a Tuareg rebellion and threats from terrorist groups that had moved into parts of Niger and neighboring Mali.

Each time the expeditions returned and set up their tents near the ancient lake bed, the scientists wondered what they’d find. Had the desert winds finally carried away the small dunes? Had curious nomads rummaged the site? Or had it been ransacked by looters? But each time, new discoveries were exposed.

Several prehistoric middens, or garbage dumps, overflowed with bones from Nile perch and catfish and included a stack of mussel shells. Even the sand contained evidence—pollen from palm and fig trees, cattails, and other plants associated with wet areas.

A team begins brushing the sand away from a partially uncovered human skeleton at Gobero. Once bones are exposed to the Sahara’s powerful sandblasting winds, there’s limited time to collect them before they’re ground to nothing.

A team begins brushing the sand away from a partially uncovered human skeleton at Gobero. Once bones are exposed to the Sahara’s powerful sandblasting winds, there’s limited time to collect them before they’re ground to nothing.But the finds that left team members speechless were the burials. “We find every age—old people, middle age, teenagers, children, infants,” Sereno said. Radiocarbon dating puts the oldest burial, a six-foot-two man posed in a tight crouch, at around 9,500 years ago, near the beginning of the Green Sahara. The most recent burial, a 10-year-old girl wearing a large hippo ivory bracelet, occurred about 4,900 years ago—a span of roughly five millennia. “That’s about the length of time from the first Egyptian pharaoh to my grandfather,” Sereno said, “all in this one small area.”

The burials tended to fall into two broad categories. In the older ones, the bodies were buried in the same manner as the six-foot-two man, with arms held close to the torso and knees pulled up tightly to the ribs and spine, so that the skeletons resemble collapsed accordions. One theory holds that some of these had been interred tightly bundled, possibly in animal hides.

Idé, head of archaeology for Niger’s Research Institute in Human Sciences, explained that the dates of these burials suggest these people were part of what archaeologists have named the Kiffian, a fisher-forager culture that ended about 8,000 years ago. Around that time, the burials at Gobero were flooded and remained submerged for several centuries.

These burials seem to be communicating something about the deceased. When excavating a grave, archaeologists usually disarticulate skeletons if they plan to take them to a lab. Sereno wanted to preserve the most important and unusual Gobero figures in their striking poses, so he employed a technique paleontologists use to preserve dinosaur fossils. He dug trenches around some of the most interesting burials and encased them in plaster, allowing the team to remove them in situ for transportation back to his lab.

Excavating human remains is a highly sensitive subject, but there’s a compelling case to be made for studying the Gobero burials in a modern lab. The bones contain volumes of information, says Chris Stojanowski, a professor at Arizona State University who was part of the 2006 expedition. He’s been studying skeletons collected on that trip ever since. “You see all this?” he said to me recently on Zoom, tilting his camera to reveal stacks of books and papers. “It’s all Gobero research.”

Stojanowski analyzes skeletal remains to understand how humans interacted with their environment, what diseases they suffered, telltale signs of their lifestyle left on their bones and teeth. One of the most surprising things was how few injuries he found. One person had a skull fracture but had survived, because it had fully healed. Then there was a woman who’d suffered a wound to her fibula that also had healed. Embedded in the bone were rock fragments consistent with what an arrowhead would leave.

They also don’t seem to have been under significant stress from starvation, drought, or chronic illness. As teeth form, they accumulate microscopic layers of enamel-like how trees add new growth rings—and periods of high stress, including trauma, are recorded by disruptions in the layers. Hoping to shed light on the triple burial, Stojanowski had molars from the two children thin-sliced and reviewed microscopically; the results revealed no evidence of significant stress.

Another revelation was the people didn’t seem to move from place to place. With nomadic individuals, you can trace their movements by matching the signature of the strontium isotopes in their teeth—accrued from the plants and animals they ate and the water they drank—with the strontium in the bedrock at the places they visited. But the people Stojanowski has studied at Gobero show primarily one signature. “They didn’t really move much.”

Sereno has found other evidence that implies people lived year-round at Gobero. His teams have collected otoliths, the bony structures from the inner ears of fish. Like layers of enamel in teeth, otoliths grow in tiny rings, adding a new one each season. The outermost ring suggests when a fish was caught. The otoliths found in Gobero’s middens indicate the fish were caught throughout the year.

One of the biggest surprises was that out of the thousands of animal bones found at the site, only a single cow bone has been identified. Why would a herding culture like the Tenereans not show more evidence of cows? Sereno believes the answer may simply be that the people who lived at Gobero weren’t herders or nomads. “Practically everything they needed was at Gobero, and they adapted their lifestyle specifically to this place.”

Surrounded by expedition members, Paul Sereno examines a hippo fossil at Gobero in 2022. Two decades earlier, he was hunting for dinosaur bones when he stumbled onto the site. Since then, he’s returned eight times to study its ancient burials.

Surrounded by expedition members, Paul Sereno examines a hippo fossil at Gobero in 2022. Two decades earlier, he was hunting for dinosaur bones when he stumbled onto the site. Since then, he’s returned eight times to study its ancient burials.When Sereno arrived in Niger in 2022 after being away for three years, the usual difficulties awaited him. A West African air traffic controllers’ strike suspended flights to Agadez. Meanwhile, the Niger military was called on to provide security for a traditional festival, so the expedition’s escort of soldiers was delayed. Sereno was trying to squeeze a lot into this expedition—there were several dinosaur sites to excavate—but he’d saved four days for Gobero. Yet, as the delays mounted, the four days were cut to one.

When the convoy of Land Rovers and military vehicles finally rolled up to Gobero, I hardly recognized the place. A line of large sand dunes east of the site that I’d used to get my bearings in 2006 had shrunk and retreated into the distance. A few sparse stands of acacia trees near the lake bed had grown into a small forest filled with insects and chattering birds. I even startled a large desert hare that bolted from behind a tuft of bunch grass.

Sereno hurried up one of the dunes to check on a burial he’d planned to excavate, and other members of his team spread out to look for fossils and artifacts. I followed a Nigerien archaeologist named Boubé Adamou out onto the dry lake bed. Known as a keen-eyed bone finder, he always seems to spot what others miss. “He’s relentless,” Sereno said.

Adamou moved at a slow, deliberate pace, scanning the sandy hard pan. The sun beat down on our backs. After all these expeditions and the harsh conditions, what could be left? Suddenly he pointed, and there was a bone harpoon point with its unmistakable serrated tip lying on top of the lake bed where thousands of years ago it had been hurled by a hunter aiming at prey in shallow water.

By mid-afternoon, a camp table was covered with the finds, including several bone harpoon points, large grindstones, arrowheads, hippo and fish bones, and crocodile scutes. The grave Sereno wanted to excavate, it turned out, was of a woman buried with a large turtle shell, like one previously found with a man. Were they somehow connected? Why were turtle shells so important? Some kind of marker of the Gobero people’s identity? An item needed for the afterlife? Another clue, another mystery.

Last winter, Sereno invited me to Chicago to visit his laboratory, which holds a menagerie of ancient creatures worthy of a museum. A Sarcosuchus skull—large enough for me to fit inside its gaping jaws—guards the door. A model of Nigersaurus with its wide, flat mouth stares out from atop a cabinet alongside a full skeleton of an Eoraptor perching on two legs with a long, curving tail. There are feathered theropods, an armored dinosaur that hasn’t been formally named, and a Jobaria skull the size of a truck engine—all discoveries that Sereno and his colleagues have unearthed and described.

Gobero is there too. Endless rows of drawers contain thousands of artifacts and animal bones. I recognized a giant tortoiseshell found in the lake bed and a large Tenerean pot. Sereno, who is 66, plans to return all the material, including the burials and dinosaur bones, to Niger in stages over the next 15 years. To that end, he’s busy working with Idé and others to build two museums to house it all. He showed me architectural plans for one to be built in the capital, Niamey, and a smaller one for Agadez, the nearest city to Gobero.

But the fieldwork isn’t finished. Sereno hopes to collect at least one more skeleton. At the end of the 2022 expedition, he and the team briefly returned to Gobero to retrieve the woman with the turtle shell. As they dug, Adamou, the bone finder, noticed the skull of a child, and while they were excavating that burial, they uncovered the foot of another skeleton they dubbed “DNA Man.”

But because the burials aren’t deep and have been subjected to desert sun and heat for millennia, the collagen in the bones and the dentin in the teeth, good sources for DNA samples, are too degraded. “I always thought if I could find a burial that was deeper than the others, we might get a viable sample,” Sereno said. DNA Man, who is about a foot below the surface, might’ve been protected just enough.

Lack of time once more prevented Sereno from collecting a skeleton. He covered the burial and marked the spot, hoping someday to come back. Again. “Gobero just won’t let go of me,” he said, laughing.

Now things are even more difficult in Niger. Last July, a military coup deposed the democratically elected president. In March, its leaders ordered the U.S. military to close the drone base and leave the country. It seems unlikely Sereno will return to the desert for some time.

(How a trip through the Sahara reflects Niger’s fragile state.)

Over the years the team has culled new details. The three were buried around 3400 B.C. The woman, between 25 and 35 years old, had been laid in the grave first, followed by the seven-year-old and then the five-year-old. Four perfectly shaped arrowheads had been added, and pollen found beneath the bones revealed they’d been interred with wool flowers.

There’s no evidence to prove this was a mother and her children, but that’s how my imagination fills in the story. There’s no way of knowing who buried them, but I can’t help but look at this scene as a husband and father. And I can’t help but read the message that their burial seems to convey as one of love and profound loss. It’s the first time I’ve felt an emotional connection to prehistoric people. But 5,400 years later, I feel their sorrow.