How a molar, jawbone, and pinkie are rewriting human history

Stunning discoveries and fresh breakthroughs in DNA analysis are changing our understanding of our own evolution and offering a new picture of the “other humans” that our ancestors met across Europe and Asia.

Deep inside Cobra Cave, in the remote mountains of northeastern Laos, the beam from Eric Suzzoni’s headlamp bounced across barren rock until it flashed on something unusual: dozens of bones and teeth protruding from a layer of sediment and rock.

Suzzoni, a tall, 50-year-old caving specialist with a tiger tattoo on his arm, yelled out to his partner, Sébastien Frangeul. This was the French explorers’ first foray into Cobra Cave. They had just scaled 65 feet of limestone cliff, ascending from the forest floor to the cave’s entrance with their unlikely companions: a pair of local teenagers in flip-flops. The Hmong boys knew the terrain around the cave and the namesake cobras that sometimes lurked inside. Today the snakes were nowhere to be seen. But soon after climbing into the cave, the explorers had stumbled upon what appeared to be a trove of ancient fossils.

Suzzoni and Frangeul were scouting this cave for an international team of paleoanthropologists excavating sites nearby. For more than 15 years, the scientists had been digging in these mountains, searching for clues to some of the deepest mysteries of human evolution: When did Homo sapiens arrive here? And what other humans did they encounter>

Suzzoni didn’t dare touch the fossils at first. But when he returned to survey the cave the next day with one of the research team’s geologists, his task was to pry loose a sample of the sediment from the cave wall. As he tapped on a chisel, a large brown tooth tumbled out, a molar that looked eerily human. Suzzoni hadn’t intended to make a find—by protocol and profession, that was the scientists’ job—but he marveled at the specimen for a moment and slipped it into his shirt pocket. It was, he says, “a beautiful gift.”

(Tooth from mysterious human relative adds new wrinkles to their story.)

A molar in Laos, a jawbone on the Tibetan Plateau, the fragment of a pinkie in Siberia. Our evolutionary history is now being rewritten by tiny discoveries illuminated by fast-advancing science—breakthroughs in ancient genetics, the study of proteins, and radioactive dating. The flood of new insights is not only radically changing the understanding of our origins; it is challenging the very notion of what it means to be human.

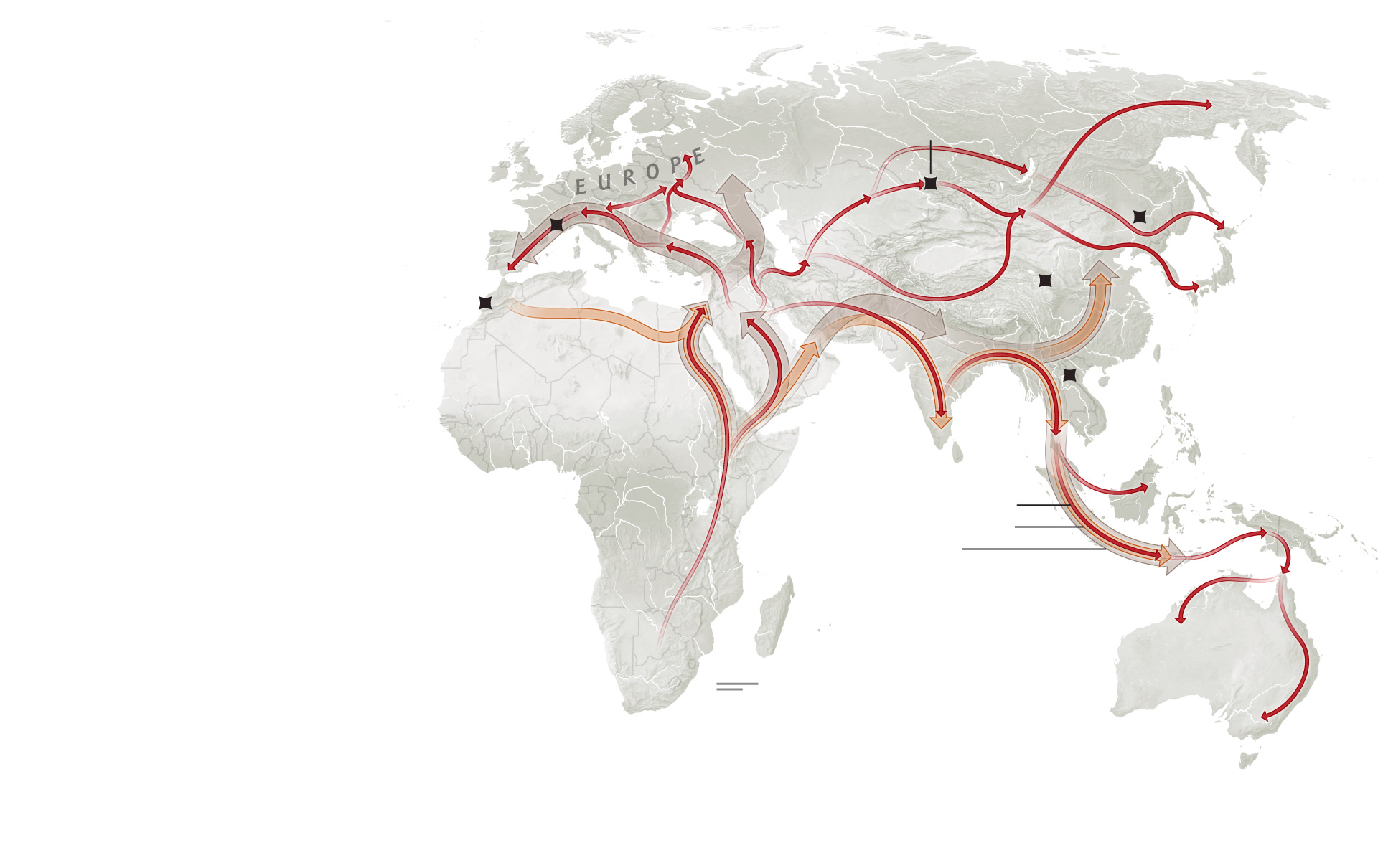

How early humans migrated and mixed. Homo sapiens are the only humans left on Earth today, but at one point, we shared the planet with other species of ancestral humans, collectively known as hominins. As climates and ecological opportunities shifted, hominins migrated out of Africa, reconnecting and interbreeding with the descendants of their relatives who had made similar journeys thousands of years before.

All of us, all eight billion people on this planet, belong to a single species. We Homo sapiens are the last hominins on Earth. Not long ago, it was widely believed that modern humans followed a relatively straight path of evolutionary progress as we fanned out of Africa, one that was separate from—and, implicitly, superior to—that of other species. Even today, one of the most indelible images of evolution is the so-called March of Progress, an illustration plastered on T-shirts and posters that shows our predecessors improving their posture as they progress inexorably to Homo sapiens, tall and proud, striding into the future.

The current upheaval in evolutionary thinking has shattered that neat, linear view of human origins and begun to replace it with a far more tangled picture. What researchers now know is that between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago—a critical period in our evolutionary development—the world teemed with human variety. And as Homo sapiens radiated out across Europe and Asia, they encountered and at times even mated with other types of humans. Evidence of this commingling came in 2010, when Swedish paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo mapped the Neanderthal genome for the first time. His work proved that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens procreated—and that the genetic exchange had profound and lasting consequences. Today, more than 40,000 years after the Neanderthals went extinct, most human beings alive carry remnants of their DNA. But who else shared the planet with us? And how did our interactions with these other humans shape the course of our own evolution and their extinction? Paleoanthropologists are delving ever deeper into these questions—the same ones that Demeter and Zanolli faced as they studied their mystery tooth from Cobra Cave.

(Multiple lines of mysterious ancient humans interbred with us.)

The Denisovans, as Pääbo’s team dubbed them, became the first human group ever identified solely through DNA—a ghost species, as experts call those without a physical identity. Denisova Cave yielded more fossils with their DNA. These included a bone from a girl who had a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother—the only first-generation hybrid hominin ever discovered.

From the finger fragment, geneticists were able to trace Denisovan DNA in modern-day populations all over the world, from Iceland to Peru, with especially high concentrations in Papua New Guinea, 5,500 miles away from Denisova Cave. Homo sapiens almost certainly interbred with Denisovans as well as Neanderthals and carried their DNA across the planet. Paleoanthropologists now believe these “gene-flow events” were not an anomaly but a central feature of evolution, helping Homo sapiens adapt to new environments and leaving most of us with a direct biological link to extinct groups of ancient humans.

For all the advances in genetic and protein research, understanding how Denisovan genes made it to Papua New Guinea or why Neanderthals and Denisovans, after nearly half a million years of existence, disappeared once Homo sapiens arrived will require more fragments of ancient bones and teeth. After more than a century of digging, the fossil record of our best-known relative, Neanderthals, is comparatively sparse—bones from about 400 individuals. The Denisovan record is vanishingly small. All of the Denisovan fossils ever found could fit into a bread box, and there’d still be room for bagels.

High on the Tibetan Plateau in China’s Gansu Province—in a cave hollowed out of a cliff some 11,000 feet above sea level—a Buddhist prayer site has become a remarkable locus of scientific discovery. Long before the bones found there acquired value to modern researchers, they were ground to make medicines and elixirs. So it’s perhaps something of a miracle that an ancient jawbone found in Baishiya Karst Cave in 1980, now commonly known as the Xiahe mandible, still survives. The monk who discovered it brought the bone to his leader, the sixth Gung-Thang Living Buddha, who bequeathed it to Chinese scientists. The mandible sat on a shelf for years, unidentified and almost forgotten. But several years ago, inspired by the discoveries in Siberia, Lanzhou University archaeologist Dongju Zhang joined some colleagues in trying to solve the riddle of the bone’s identity.

Then in her mid-30s—the bone had been languishing at the university for almost as long as she’d been alive—Zhang initiated a delicate excavation in Baishiya Karst Cave alongside the meditating monks. But obstacles abounded. The jawbone’s muddled oral history didn’t specify exactly where in the cave it had been found. Even more confounding: The jawbone had no trace of DNA. The only information came from the carbonate crust still clinging to it, which uranium-thorium dating estimated to be at least 160,000 years old. The jawbone was by far the earliest trace of human presence ever discovered on the Tibetan Plateau. Intriguing, yes, but it got Zhang no closer to identifying the fossil.

On a work trip to Europe in mid-2016, Zhang, eager for help, met with a graduate student experimenting with a method of analysis that promised to go beyond DNA. Frido Welker was just 25, but he was already breaking new ground in a developing field, paleoproteomics, which functions like a deep-time machine. The tousle-haired Dutchman explained to Zhang how he analyzed ancient proteins that persist in fossils far longer than DNA—sometimes two million years longer. Proteins follow patterns set by DNA, so they act like shadow DNA, echoing information long after the original is gone. Still, Welker warned Zhang that extracting proteins is typically invasive—a hole must be drilled into the fossil—and there is no guarantee of success. “I felt a huge responsibility for this precious artifact,” Zhang recalls. “But we needed to find out what it was, and I was out of options.”

Zhang’s last resort eventually became Welker’s first big chance, what he calls a “scientific opportunity” for his nascent field. The protein material was extracted in China—Zhang recalls how nervous she was handing over the mandible to be drilled—and Welker, now at the University of Copenhagen, then analyzed it with a mass spectrometer in a German lab. The patterns of the collagen protein found in the jawbone confirmed that the fossil was, in fact, Denisovan.

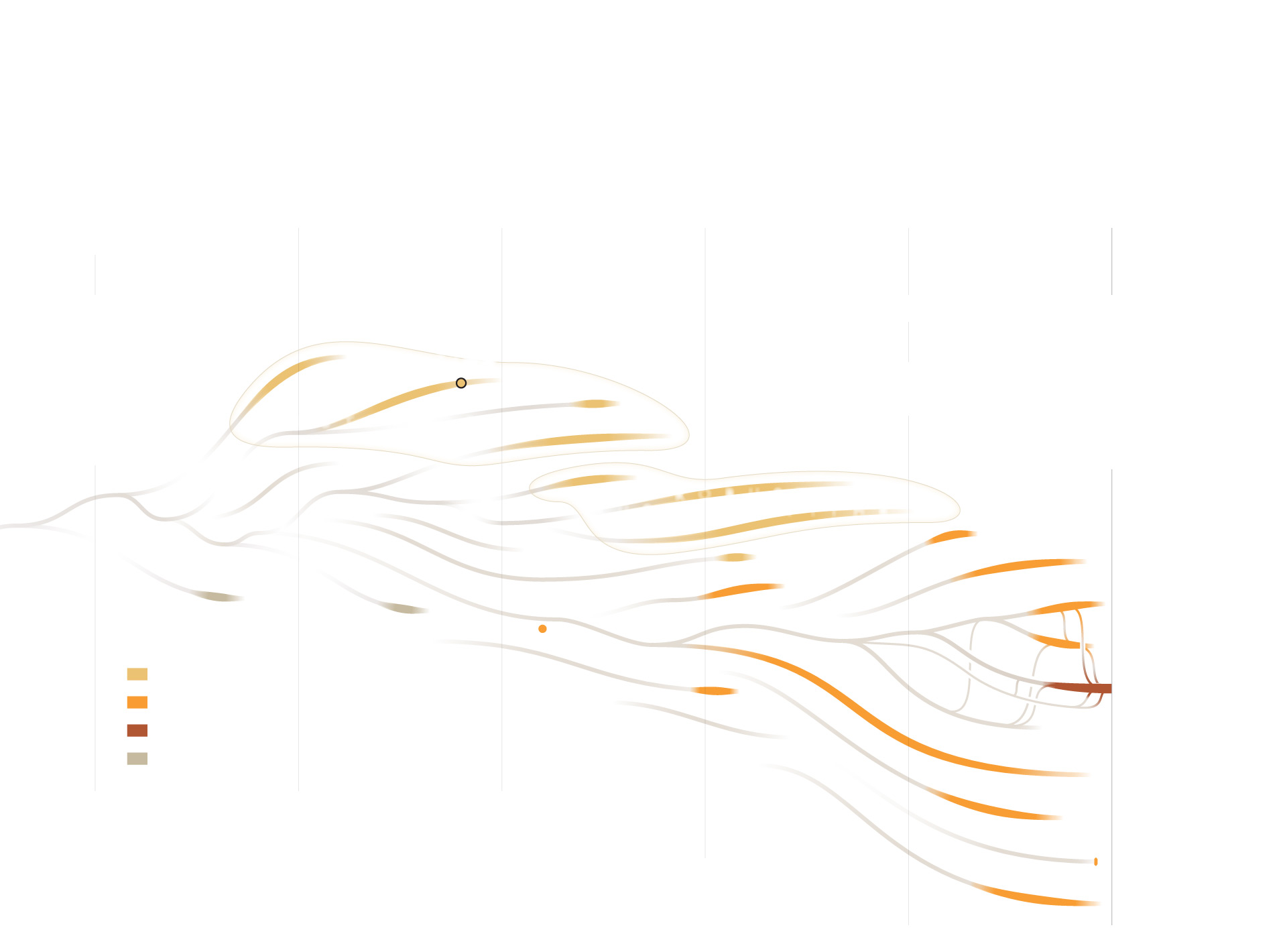

Reimagining how humans evolved

Homo sapiens are a terminal species, meaning we are the only ones left from a group of multiple species that occasionally coexisted and sometimes even interbred. These separations and rejoinings of our various lineages have led some scientists to think of human evolution as less of a traditional family tree and more of a meandering “braided stream.”

Australopiths lived in many habitats, stretching from grasslands to forests, and eventually gave rise to hominins in the genus Homo. Robust australopiths had strong jaws and large molars specialized for foods like grasses that were available in open habitats.

Homo sapiens are the only remaining humans. Our genus, Homo, features relatively larger brains, full bipedalism, and the ability to make tools. Lucy ~3.2 mya

The revelation marked the first time an ancient human had been identified solely through proteins. The jawbone, moreover, was the first evidence of Denisovans existing outside of Denisova Cave—enriching the picture of a species about which nearly nothing was known. The breakthroughs have continued, and the story of the Denisovans in the Tibetan Plateau cave has grown more detailed. A year after their discovery, Zhang and her team found traces of Denisovan DNA in Baishiya Karst Cave, further confirming their presence there. Last summer, Welker and his Chinese colleagues again used proteomics—and a Denisovan rib bone—to show that Denisovans had inhabited the cave off and on for more than 100,000 years, butchering and consuming a wide range of wild animals. “Adding a piece of the puzzle is a unique experience,” says Welker, “because every new piece changes the arrangement of all the rest.”

Welker’s point, about how one discovery can change the meaning of another, is underscored by the jawbone that he and Zhang revealed. Their work identifying the mandible meant that Denisovans now had an “anchor point,” a bone that could serve as a basis of comparison for other fossils, whether found in a dusty Chinese collection or, say, in a cave in Laos. This is precisely what Fabrice Demeter needed. He’d been carrying around the mysterious molar from Cobra Cave, trying to find ways to extract information from it, but no viable DNA could be found in the tooth. Not even paleoproteomics could help, as the tooth’s proteins were too limited for a conclusive reading. The only thing Demeter could determine was that the tooth was human and belonged, 160 millennia ago, to a young girl.

But when he learned that Zhang and Welker were set to publish a journal article unveiling the Denisovan jawbone, Demeter knew he and Zanolli, the tooth expert, could compare their molar with the two teeth on the jawbone. They discovered that one of the teeth was almost identical to the Cobra Cave molar. It was a morphological match, not an indisputable genetic one, but Demeter felt vindicated. “Maybe we had some luck,” he told me last year, as his team gathered at the Laos cave site. “But we’ve been digging here for 21 years! Now our work is finally paying off.”

(Ancient teeth hint at mysterious human relative.)

Cobra Cave marks the third place in the world where a Denisovan fossil has been found. It is also the first one discovered in a subtropical environment, about a thousand miles south of the high-altitude Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau and 2,000 miles southeast of the frigid Denisova Cave, suggesting that Denisovans roamed widely and adapted to many different environments. As more Denisovan geographic markers are confirmed, and as their location and timeline continue to overlap with those of other hominins—in particular, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens—more genetic puzzle pieces fall into place.

In 2014, five years before the Xiahe mandible was identified as Denisovan, population geneticist Emilia Huerta-Sánchez at Brown University made a surprising discovery about ancient DNA: She found that the gene known as EPAS1, which helps Tibetans live comfortably at high altitude without getting hypoxia, came not from modern humans but from Denisovans. (The pinkie from Denisova Cave gave her the only nearly perfect DNA match.) When Welker and Zhang confirmed in 2019 that Denisovans had inhabited the Tibetan Plateau, the connection made perfect sense. Tibetans put this gene to use, Huerta-Sánchez says, even though they carry only a small remnant of Denisovan DNA—and arrived on the plateau tens of thousands of years after the interbreeding took place. “You don’t need a lot of archaic DNA for it to be beneficial or useful later on,” says Huerta-Sánchez, who is now studying a Denisovan gene prevalent in the Americas. Even a small amount, she says, “has a huge impact on people, as it did with Tibetans.”

The consequences of ancient interbreeding are still poorly understood. But geneticists like Huerta-Sánchez believe it served a vital evolutionary purpose. Not only did all that mating inject much needed genetic diversity into Homo sapiens populations. The gene flow gave modern humans evolutionary shortcuts to adapt more quickly to extreme environments: staving off hypoxia in Tibet, for example. This bolstering of the immune system likely helped Homo sapiens spread across the world.

But the impact hasn’t all been good. Scientists are finding that some of the genes inherited from Neanderthals and Denisovans are associated with depression, autism, or obesity. Interbreeding, moreover, didn’t seem to help the Neanderthals and Denisovans. Though remnants of their DNA live on within us, their genomes show no trace of modern humans—and some scientists believe that interbreeding with Homo sapiens may even have hastened their demise.

(DNA reveals first look at enigmatic human relative.)

Ludovic Slimak is obsessed with the moment when Homo sapiens might have pushed other human species out of the evolutionary picture. The French paleoanthropologist with the University of Toulouse III has chased the ghosts of Neanderthals from the Horn of Africa to the Arctic Circle. For the past quarter century, he and his wife, archaeologist Laure Metz, have spent much of their time digging and thinking in Grotte Mandrin, a cave in southern France inhabited at different times more than 42,000 years ago by Homo sapiens and some of the last Neanderthals. It’s just a small rock overhang, but the human story it tells “is really universal,” says Slimak. “I use Neanderthals as a mirror to try to see ourselves more clearly.”

Slimak’s pursuit has led him to study the period when Homo sapiens emerged from Africa, entering territory inhabited by Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other late hominins: the ghost species. This was a critical moment, the 52-year-old believes, when the last of these other humans were carrying out their own experiments in humanity—experiments that he strives to understand not just from a genetic perspective but from a behavioral one too.

Scurrying around his office high in the rafters of his medieval home, Slimak shows me stone flints found in Grotte Mandrin. “When you take Neanderthal tools, each is unique,” he says, pointing out the variations in shape, color, and size. Living in small, isolated groups across Europe, Neanderthals displayed a creativity—and a sensitivity to their environment—quite unlike early Homo sapiens, whose tools and weapons were almost identical from the Levant to western Europe. Neanderthals, Slimak says, “perceived and engaged with the world in ways profoundly different from those of Homo sapiens.”

The discovery in Grotte Mandrin of one of the last Neanderthals in Europe has prompted Slimak, a National Geographic Explorer, to think deeply about how the divergent natures of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals may have led to the latter’s ultimate demise. The skeleton, which Slimak named Thorin after the dwarf king in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, was found a decade ago. Slimak’s team has been slowly unearthing it ever since, using tweezers to remove grains of sand and fragments of bone. After nine years, they’ve recovered parts of Thorin’s skull, 31 teeth, and a large number of tiny, unidentified bones.

The root of one tooth still had viable DNA, which yielded an astonishing insight, just recently unveiled. Thorin’s group inhabited Grotte Mandrin about 42,000 years ago and had been in genetic isolation for the previous 50,000 years, never even mingling with other Neanderthals living a few valleys away. For Slimak, this was further evidence of a deeper Neanderthal lineage—and of how different Neanderthals were from modern humans.

Paleoanthropologists have debated the causes of the Neanderthals’ extinction for years and will surely do so with Denisovans as their timeline and geographic spread become clearer. Denisovans and Neanderthals seem to have vanished from the fossil record at roughly the same time. There is a growing consensus among paleoanthropologists that the Neanderthals’ disappearance owed primarily to a demographic crisis—a dwindling population with limited genetic diversity—exacerbated by climate change and the emergence of a powerful rival, Homo sapiens. Interbreeding may have played a role too. Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London and National Geographic Explorer, suggests that Neanderthal females may have been absorbed—or abducted—by dominant sapiens groups, pushing Neanderthals to the edge of the demographic abyss.

(Ancient DNA reveals new twists in Neanderthal migration.)

The disappearance of the Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other groups around 40,000 years ago marked the end of millions of years when multiple groups of hominins walked the Earth. The current epoch is a historical anomaly, and Stringer advises us not to be smug in our status as the last ones standing. Neanderthals and Denisovans survived for half a million years; Homo erectus lasted nearly two million years. At the rate we’re going, how successful will we look in 2,000 years, much less a million?

Back in a rice field in northeastern Laos, Eric Suzzoni is leading Fabrice Demeter’s team of scientists toward a new cave several miles north of their base camp.

For the past two decades, the international team has worked on a single mountain, excavating a cluster of caves that has yielded a rare trifecta of ancient human species: In addition to discovering the Denisovan molar, the team has unearthed fossils of ancient Homo sapiens in one cave and, in another, a 130,000-year-old tooth most likely from Homo erectus. “That is an incredible result, but we’re also looking at just one site,” says Laura Shackelford, an American paleoanthropologist with the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a National Geographic Explorer who began working with the team in Laos in 2008. Denisovan remains “have to be all over the place, and we just haven’t found them yet.”

The future of the distant past seems to lie in Asia, a region that Demeter calls “a blank slate compared to Europe.” It started with the astonishing discovery of two diminutive “hobbit” populations—Homo floresiensis in Indonesia in 2003 and Homo luzonensis in the Philippines in 2019. But the focus has now shifted to China. Ever since the Xiahe mandible was identified in 2019, Chinese paleoanthropologists have raced to reexamine the country’s vast fossil collections—dusting off their “cold cases”—to see if they too might contain Denisovan relics. Two archaic jawbones—one dug up west of Beijing, the other dredged from the Taiwan Strait—are close physical matches with the mandible. If their identity is confirmed, as expected, it will mean that Denisovans ranged over all of mainland Asia—perhaps centering on what is now Chinese territory.

Chinese researchers have begun to reshape long-standing assumptions about when we branched off from our fellow hominins. A recent phylogenetic study of one Chinese skull pushed back our divergence from Neanderthals and Denisovans by 300,000 years, shaking long-held beliefs about whether our common ancestor even lived in Africa. Then there’s the Harbin skull. Found in 1933 by a worker in northeastern China and hidden in a well for the rest of the 20th century, the 146,000-year-old fossil could belong to a hominin relative closer to modern humans than either Neanderthals or Denisovans—a tantalizing clue that inches us nearer to the identity of our common ancestor. Some scientists think the Harbin skull could represent a branch of the Denisovan family or even a completely different lineage. Local paleoanthropologists gave the lineage a distinctly Chinese label: Homo longi, or Dragon Man. (The Harbin skull was the basis for the model constructed by paleoartist John Gurche.)

Over the past few years, Beijing has invested heavily in genetics and paleoproteomics labs—and in a new generation of scientists—to close the research gap with the West. Unlike Laos, China does not allow human fossils to leave the country for analysis, nor does it offer much access or transparency for foreign scientists. Many young Chinese scientists like Dongju Zhang, however, nurture a spirit of collaboration. Last summer, she invited a dozen foreign scientists, including Welker and Demeter, to western China for an international symposium on Denisovans. “We cannot work and publish alone,” Demeter says. “I need their help, and they need ours.”

Venturing into the new Laotian cave—called Tam Neun—Suzzoni and the team of scientists entered the realm of the distant past. Time collapsed. And the remnants of ancient floods became apparent. Deep in the cave, geologist Philippe Duringer trained his headlamp on multiple thin layers of limestone encasing thick seams of sediment and rock, known as breccia. “That flowstone took thousands of years to form, but the sediment flooded in here in a single event, maybe in a single day,” he said. Near the back of the cave, tiny shadows appeared on the wall—silhouettes of bones and ancient teeth sticking out of the breccia, all entombed on that day more than 50,000 years ago. Suzzoni wriggled into the cave’s deepest chamber on his back, his face inches from the fossil-encrusted ceiling. Maybe, with a little luck, he would make another discovery that would change the map of human evolution.