Are these the last days of Brazil’s realm of hidden wonder?

The largest agricultural boom on the planet threatens to destroy a spectacular savanna. Here’s what happens when progress outpaces preservation.

February 11, 2025 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

It’s called the Cerrado, Portuguese for ‘closed,’ and for nearly all of human historythis vast tropical savanna in central Brazil seems to have been shut off from the rest of the world. People do live there; hunter-gatherer groups, overcoming the formidable wilds, have roamed the Cerrado since the Stone Age. And in colonial times, those escaping slavery often disappeared behind the hills, where they built tight-knit communities, unlocked the land’s subtle gifts, and settled in. Otherwise, across centuries, hardly anyone ventured inside.

The terrain was repellent to visitors, practically impossible to traverse. Much of the Cerrado is a dense, tangled mess of stunted trees and shrubs, the whole place crawling with snakes. It pales in lushness to the mighty Amazon rainforest to the north, the green lungs of the Earth. Even some scientists who study the Cerrado call it ugly; the common term for its scrubland is —“dirty field.”

But the main reason the Cerrado was ignored beyond Indigenous peoples and those seeking refuge is that no one could find money in it—no hardwoods, no diamonds, no oil. The soil is highly acidic, deadly to most non-native plants, and during the six-month dry season the land is often ravaged by fire. Until the mid-20th century, the Cerrado was dismissed by the capitalist world as a wasteland. Best to leave it closed and move on.

In the 1950s, Brazil found a use for it. The nation, leaping into the global economy, decided to construct a new capital city, a monument to Brazilian progress, in the center of the country. So a hunk of the Cerrado, smack in the middle, was cleared, and Brasília rose up. Five million people now live there; only São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Belo Horizonte are bigger.

Then, in the 1970s, came a more sweeping transformation. Brazilian agricultural scientists working in a government lab cooked up a fertilizer, packed with lime, that modified the harsh Cerrado soil and enabled cash crops to grow. Industrial watering systems could counteract the dry season, and fire brigades would snuff out the flames. The Cerrado was open for business.

Bulldozers and tractors rolled in, and thousands of square miles of scrubby Cerrado were scraped clean. Corn, sugarcane, and especially soybeans were planted, then trucked across the country to seaports. China, the United States, and Europe bought them up, and the land clearing intensified. The largest agricultural corporations in the world established massive factory farms there. The Brazilian economy roared. More land was churned up; there seemed no limit: The Cerrado’s size is Texas times three. The area, according to a 2021 report from the World Bank, has “the greatest agricultural potential on the planet.”

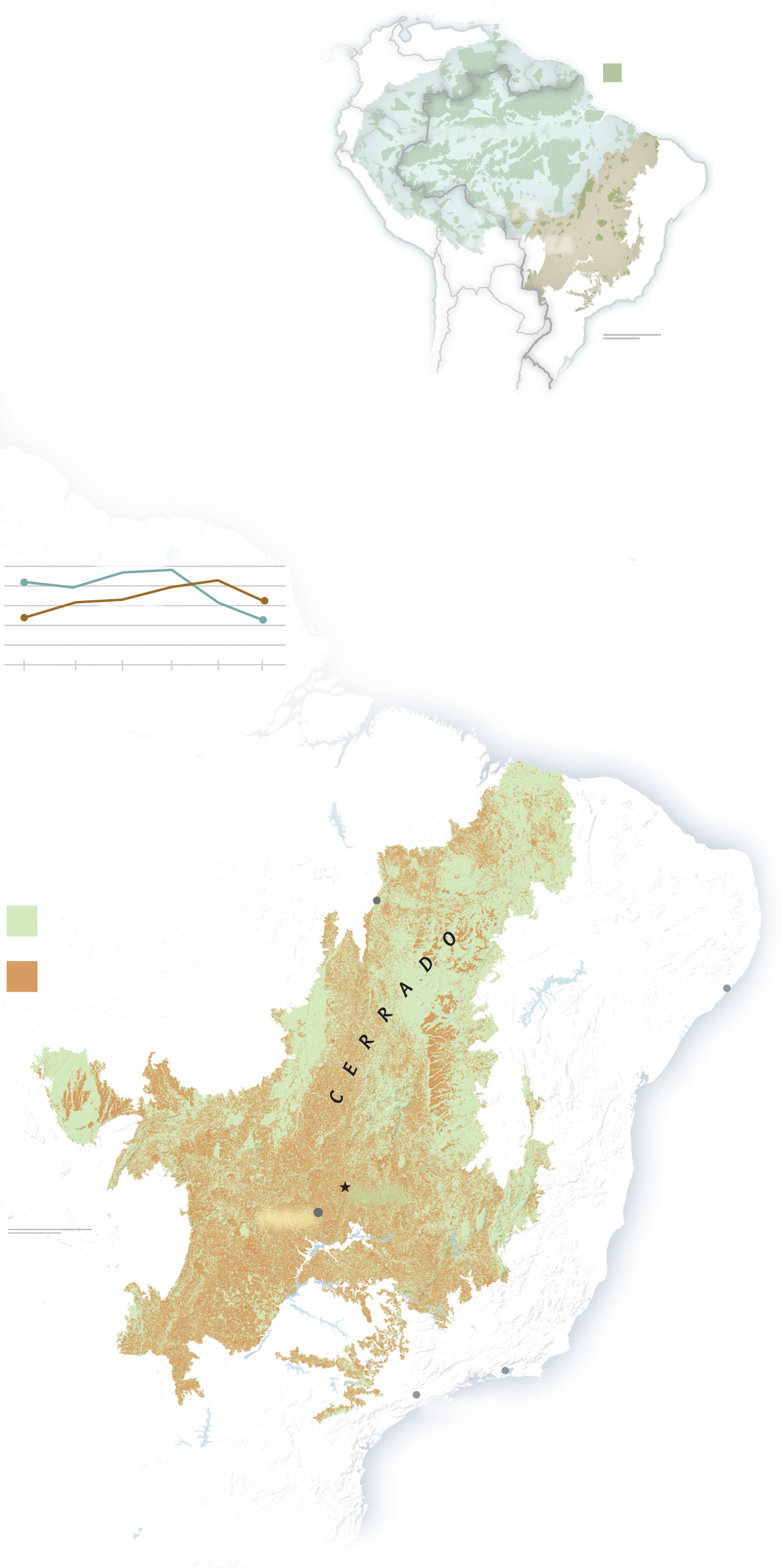

How Brazil’s Cerrado is Changing

At the edge of the Amazon rainforest Brazil’s lesser known, less protected, and second largest ecosystem, the Cerrado, is rapidly transforming. Its diverse savannas, grassland, and forests house some 5,000 endemic species, whose habitats are vanishing at extreme speed.

Deforestation in the Cerrado increased by 68 percent between 2022 and 2023, prompting new efforts to protect the area.

Brazilian deforestation by year: Amazon 5,000 square miles

Vanishing landscape. The cerrado’s natural vegetation is being cleared to make way for cattle grazing and crops including soybeans, rice, and sugar.

Along with government workers and farmhands, a new generation of biologists, many lured by the science department at the University of Brasília, also came to the Cerrado, curious about this relatively unknown region, always considered less worthy of study than the Amazon. Over the past two decades, scientific attention has focused on the area even as it has shifted toward becoming an ecological “sacrifice zone”—what land-use experts call a place, lacking strong environmental protection, that caters to human consumption. And the Cerrado’s great secrets have emerged.

Turning away most humans for millennia appears to have been an ideal strategy for preserving extraordinary biodiversity. The Cerrado, researchers from the University of Brasília and elsewhere have tallied, is home to more than 11,000 species of plants and trees, 40 percent of which exist nowhere else. There are 800 bird species, 1,200 fish species, and 90,000 insect species. The golden-furred, stilt-legged maned wolf prowls the Cerrado, as does the giant anteater, which grows up to seven feet long, not including its two-foot tongue. There are wide populations of bees, snakes, lizards, bats, and butterflies. About 5 percent of Earth’s animal and plant species are thought to live in the Cerrado, the biologically richest savanna in the world.

(Discover all 25 of the best places to visit in 2025, including the Cerrado.)

The real secret, though, is what you can’t observe. The soil in the Cerrado runs deep, in places 80 feet, and to help survive the dry season and its fires, many plants sprout extensive root systems. The vast majority of the Cerrado’s biomass is subterranean. Some trees that look like spindly fence posts aboveground are muscle-rooted and brawny below. Biologists who examine this hidden realm call the Cerrado the upside-down forest.

This underground world performs priceless ecological services. It’s a massive carbon sink, locking away billions of tons of carbon dioxide in well-buried roots. As the Cerrado is converted to farmland—the current rate is more than 4,000 acres a day—the greenhouse gas is released. Each year, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the discharge due to altering the Cerrado is equivalent to the annual emissions of 50 million cars. If all the carbon held by the Cerrado were discharged, this might single-handedly push global warming over the 1.5-degree Celsius limit set by the United Nations at the Paris climate conference of 2015, a point at which the global ice sheets could inexorably melt, causing the seas to inundate every coastal city.

To get to a place where the Cerrado’s pulse can be experienced untamed and raw, take the road north out of Brasília. It first runs arrow straight through the suburbs, then direct to the factory farms. Rows of soybeans roll to the horizons; grain trucks outnumber cars. Tractors spray the fields with white mist. More than 150 million gallons of pesticides, Brazilian environmental journalists report, douse the Cerrado each year. “The land has been decimated,” says Brazilian ecologist Paulo Oliveira, editor of The Cerrados of Brazil, a book that explores the natural history of the region. And soybeans, for the most part, aren’t eaten by people—they’re shipped around the globe to feed cattle. The world demands beef.

After a couple of hours of driving, the windshield spattered with bugs, hills rise up, the giant farms dissipate, and the Cerrado exists in a natural state. The terrain, admittedly, can appear weird. Soil toxicity meddles with tree growth, making the trunks all gnarled and hunched. The frequent fires scorch the buds at the ends of branches, which are replaced by lower buds that grow at contorted angles, then those eventually get fire-burned too, and so on. It’s basically a big thicket of elbows.

Though not every Cerrado landscape looks Dr. Seuss strange. The Cerrado is one huge, interconnected biome composed of a dozen varieties of smaller ecosystems, ranging from open grassland to dense, full-size woods. Driving deeper in, some 150 miles from Brasília, travelers approach Chapada dos Veadeiros, one of the national parks in the Cerrado, where sections of closed-canopy forest shroud tumbling rivers. There’s a tourist town here, Alto Paraíso—High Paradise—where a steady stream of visitors, primarily from other parts of Brazil, hire certified hiking guides, lounge in streams, and purchase genuine Cerrado crystals, from pendant-necklace size to paperweight, dug from the ancient soil and perfect, say the shopkeepers, for cleansing your aura.

This is where the battle for the Cerrado is being waged, between those who cherish the otherworldly place as it is and those bending the land to their will. Less than 10 percent of the Cerrado falls under any environmental protection, mostly state parks and mixed-use areas where people live and grow crops. Only 3 percent is under full federal preservation. The national parks are just specks in the vastness. By comparison, about half of the Amazon biome is protected—and the Amazon is specifically named in the Brazilian Constitution as a national heritage zone, but not the Cerrado. An estimated four-fifths of the entire Cerrado has already been disturbed by human activities, almost everything happening in the past 50 years. No one knows how many unique species of plants or animals have already been lost.

(Explore the mystery and wonder of the Amazon in this interactive special issue.)

International conservation organizations like WWF and Global Witness, as well as Brazilian groups such as the National Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado, have mobilized. They seek to spread awareness of the Cerrado and its precarious situation and implore the Brazilian government to safeguard what’s left. A team of Brazilian forestry scientists, in a notable 2017 paper, demonstrated that the Cerrado’s essential ground layers, which contain most of the endemic species, are painfully slow at self-repair; a section of cleared land that had been abandoned for more than 20 years hardly seemed to regenerate much biodiversity.

And the agribusiness, undeniably, is helping keep the economy of Brazil, and the globe, rolling along. At the same time, the National Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado and science journalists have reported about the particularly convenient and widespread belief that nothing is really being lost—agricultural lobbyists have indicated to legislators that the Cerrado’s last untouched places are little but infertile, uninhabited regions just waiting to turn a profit.

Luciana Santos begs to differ. She was born in the Cerrado and lives there still, with her husband and four young daughters. Her family is part of a community, a collection of villages known as a quilombo, whose first members escaped slavery some 250 years ago. Here, enfolded into the hills just beyond the boundaries of Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park, the roads remain unpaved, and electricity hasn’t yet reached the farthest thatch-roofed homes.

Santos is 33 years old; when she was young, she had to walk two hours to get to school each way, though her daughters don’t do that—there’s a new school in her village that becomes a community library at night. Currently, there are 44 separate quilombos in the Cerrado and about 80 different Indigenous ethnicities whose ancestors stretch back to pre-European times. Some hunt, some farm, some fish, some graze livestock. Everyone sings different songs. An accurate census of the Cerrado is elusive, but about 100,000 people are believed to live traditionally off the land. Several groups do not own the legal deeds to their territory, their future destined to be fraught with lawsuits and land battles.

Santos is one of the guides. Walking the footpaths around her quilombo, she sees through the chaos of shrubs and trees and bushes, indecipherable to most outsiders, and points out ingredients she regularly uses. “These leaves make a lotion for skin care,” she says. “Brew a tea with this for muscle ache. This one’s good for bug bites.”

Tiny black frogs dart abruptly across the path. “They do that when it’s about to rain,” she says, and a few minutes later it does. Santos gained her knowledge of the natural world from her grandmother and mother—“and some from men too, but they’re harder to learn from”—and vows that she will pass on everything to her daughters. “I will not allow our culture to die.”

Prepackaged goods occasionally arrive by truck, but her community, like every quilombo, can grow all its own food. They did it for a couple of centuries, coaxing the soil to yield rice, beans, pumpkins, cassava. Nothing is sprayed with pesticides. You can drink the water right out of the streams. Chickens and cows are raised for meat, rivers provide fish, berries are plentiful.

Buriti palm trees offer roofing material and creamy fruits. Mangaba trees produce plumlike, sugary treats. But the local favorite, Santos says, is definitely the pequi—a fruit native to the Cerrado that’s a little complicated and a touch dangerous to eat, as there are needlelike spines inside that must be carefully avoided. The flavor, a trace of bitter lemon and a hint of cheddar cheese, doesn’t immediately appeal to everyone, but for those who can adapt to the taste, the pequi often becomes a prized delicacy.

The pequi, Santos implies, is like the Cerrado itself. If you’re able to adjust in just the right ways, the prickliness and oddities are not merely tolerated but deeply adored. “I have never wanted to live anywhere else,” she says. One person’s wasteland is another’s wonder.

Witnessing the Cerrado’s wild glory, while also avoiding the afternoon heat, sometimes requires departing with a guide on the national park trails before dawn. Moths flit about your headlamp, crystal fragments glint in the dark. There is a crazy amount of noise. Frogs burp, crickets squeak. A cacophony of insects greets first light. Some sound like power tools, others like kazoos, and whistles, and buzzers—a sense of teeming, infinite life.

Everywhere are twisted tree branches, the Cerrado staple, and vines dangling down like loose wires. From the undergrowth, ferns stretch their herringbone fronds toward the light. Brilliant splashes of color pop from the greenery: purple jasmine, red hibiscus. A candle bush holds up bright yellow blooms, a grand chandelier. A blue morpho butterfly circles, flying stained glass.

The air is a heavy blanket, and a loamy scent lingers. Termite mounds shaped like witches’ hats rise from the soil. A fat lizard lumbers, tongue flitting. Black ants hauling hunks of leaves to their nest look like a procession of tiny windsurfers. A breeze-triggered confetti of white petals tumbles out of a tree. Birds are constant companions—parakeets, hummingbirds, flycatchers, hawks. A toucan bobs beak-heavy through the air as if swimming the breaststroke. A pair of flamboyant macaws, mated for life, rainbow over the treetops.

But for how long? The director of Chapada dos Veadeiros National Park, a 37-year-old biologist named Nayara Stacheski, says she is fearful. The Cerrado could pass any salvageable tipping point in less than a decade. “This could all become a desert,” she says, and everyone with a stake in the Cerrado will lose.

Many Brazilian scientists who specialize in the Cerrado are in general agreement: It’s hard to halt, or even slow, the march of progress and the force of consumerism. “I’m not optimistic,” says Guarino Colli, an ecology professor at the University of Brasília who studies the Cerrado’s lizards and snakes. Colli indicates that it’s not the celebrated areas like the Amazon rainforest, for which people are willing to donate money and fight to protect, that we should worry about, but rather it is the lesser known, vulnerable lands that could determine our fate. How we treat the Cerrado is, by extension, how we will treat much of the world. What’s at risk, according to the National Campaign in Defense of the Cerrado, “is the life of every being.”

There are no simple solutions. Everyone wants inexpensive commodities; if we don’t farm the Cerrado, we will have to farm elsewhere. Eight billion people need to be fed every day. All nations seek to grow their economy. Nobody is at fault and everybody’s at fault at the same time. “We all have some responsibility for the devastation of the Cerrado,” says Colli. Soybean demand is soaring, and the expansion of farmland will almost surely continue. The lure of cheap cheeseburgers is strong. The Cerrado, it’s possible, will be a place that few will really miss, until it’s closed forever and gone.